What If America Had Never Invaded Afghanistan?

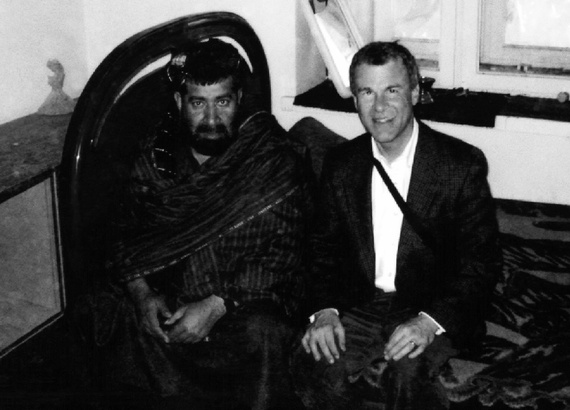

Mullah Akhtar Mohammed Osmani, the Taliban’s military leader for southern Afghanistan, sat stolidly, his great bulk supported in an overstuffed chair to my left. It was October 2, 2001, and events had been hurtling forward since the terrorist attacks of September 11. President George W. Bush had delivered an ultimatum to the Taliban in his State of the Union address on September 20: Hand over al-Qaeda’s leadership or share their fate. But the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan had not yet begun, and I still saw a chance, however small, for a peaceful way out. That was why, as the CIA station chief in Islamabad responsible for both Pakistan and Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, I was having this meeting with a top Taliban official.

The day President Bush had delivered his ultimatum, the Supreme Council of the Islamic Clergy, a committee of 700 Islamic scholars that Taliban chief Mullah Omar had convened to advise him on the correct course to pursue toward Osama bin Laden, had partially opened the door to an acceptable settlement. The council had recommended that the Taliban government seek bin Laden’s voluntary departure from the country. A day later, on September 21, Mullah Omar slammed the door shut, stating that he would neither turn over bin Laden nor ask him to leave.

On September 28, Lieutenant General Mahmud Ahmed, Pakistan’s top spy as the director-general of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), led a group of eight Pakistani Islamic scholars, well-known religious extremists all, to meet with Omar in one final, desperate attempt to induce the Taliban to, in Mahmud’s own words, “get the gun to swing away from their heads.” If there was nothing for the moment to be done about bin Laden, Mahmud suggested, perhaps the Taliban leader could agree to release eight humanitarian workers who had recently been arrested for Christian proselytizing in Afghanistan; or perhaps he could hand over some of bin Laden’s lieutenants; or at least he could allow Americans to inspect the al-Qaeda camps to demonstrate that their occupants had fled. All suggestions were in vain.

As the alternatives to all-out war against the Taliban were being systematically foreclosed, I could sense that attitudes in Washington were hardening in tandem. Even a few days before, the tone had been quite different, at least at the White House. I had already had one meeting with Mullah Osmani, on September 15, and he had told me that the Taliban would not sacrifice its country for the sake of Osama bin Laden. He hadn’t made specific concessions, but I saw a clear opportunity; for his part, the president, who had not yet delivered his public ultimatum of the 20th, had reacted to CIA Director George Tenet’s report of my meeting—and the implicit possibility of a shift in the Taliban policy of sheltering bin Laden—with open interest.

“Fascinating,” he had said.

Similarly, in late September, the president and his cabinet principals still held out the possibility of a continued role for the Taliban in Afghanistan, provided its leaders agreed to break with Omar and meet U.S. demands. All, including National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice and Vice President Dick Cheney, agreed that the United States should not hit the full Taliban leadership at the outset of its military operations, lest it discourage an intra-Taliban split.

Over a week later, though, in the face of Mullah Omar’s recalcitrance, I could feel the political landscape shifting. one could sense that all American efforts were now vectoring inexorably toward war. It was no longer clear to me that Washington would accept any deal, even if an alternative Taliban leadership were prepared to offer one. once the mental break is made, and war has been deemed inevitable, events take on their own momentum.

I also knew that my mission to the Taliban, no matter how carefully pursued, would carry with it the taint of negotiation, which had become anathema from what I could divine of the current climate in Washington. The president himself had said that there could be no ambiguity—you were either with us or with the terrorists—and that his demands of the Taliban were not up for negotiation or discussion. As a practical matter, however, even finding ways for the Taliban to meet U.S. demands would require discussion, if not negotiation, and a refusal of all discussions would scuttle any chance of non-military success. In my own discussion with Mullah Osmani, I hoped at a minimum to sow serious divisions within the Taliban leadership.

I could not rule out greater success, however, and had to contemplate the possibility that the commander and the rest of the Taliban shura, the leadership council, would reject Mullah Omar, accept U.S. demands, and find a way to turn bin Laden and his 14 most senior al-Qaeda lieutenants over to us in a bid to retain power. However remote the chance of such a peaceful conclusion to the crisis, I felt, it should not be cast away lightly. I was haunted by the thought of the disasters that had befallen both the British and the Russians in Afghanistan, and I feared that a similar fate could befall us.

* * *

I was not concerned about exceeding my authority, per se; I essentially had none, and I knew it. I had no specific instructions, really no mandate whatsoever, beyond the verbal permission for the meeting that I had made sure to get from George Tenet. Actually, I saw that lack of guidance as a blessing. In the prevailing climate, I feared, a request for guidance would have elicited a series of narrow, sterile, and pugnacious ultimatums, which would inevitably elicit a similarly knee-jerk response from the Taliban. No, I thought: better to go without talking points. If I could come up with some formula to meet Washington’s demands in a way palatable to the Taliban, I could at least present Washington with a clear proposal to which they could respond as they chose.

However it might look, my country would lose nothing from what I was doing. The worst that could happen would be that I would mislead Osmani and others in the Taliban leadership into thinking that if they broke with Omar and accepted American demands, the Americans would deal with them as a legitimate authority. If the Americans later refused to abide by such a tentative “agreement,” the damage to the Taliban’s leadership cohesion might already be irreversible—which could only be to our advantage.

The ISI had arranged for me and my translator, whom I’ll call Tom, to meet with Osmani in a small villa in the Pakistani city of Quetta. There had been no way to avoid the Pakistanis’ playing host to the meeting, but I wanted to try to keep it secret, and it seemed likely that if they wanted to monitor us, they would have to use what we referred to in the business as a “quick-plant” transmitter. Having placed one or two of these myself, I looked under every piece of furniture, searching for the telltale signs; I found none. The most obvious and simple candidate was a small handheld radio buzzer used for summoning the tea boy. I had seen such devices in ISI facilities any number of times. I had no way of knowing whether it had been tampered with, but in a surfeit of caution I disassembled it, removed the battery, and muffled it in a drawer in the bathroom.

When at last Osmani made his entrance, our meeting soon settled into the formal, almost Victorian rhythm typical of meetings conducted with a translator. I would speak a paragraph at a time, and then wait as the translator conveyed what I’d said. The advantage of that pace is that you have ample time to formulate arguments while your words are being conveyed. When receiving the response, you can devote full attention to the speaker’s body language and expression, and wait for the words to arrive later. Such meetings thus often take on the deliberate cadence of a chess match.

This one started with a rapid exchange of moves. I began by pointing out that Mullah Omar had, in effect, declared himself an enemy of America by refusing to ask bin Laden to leave Afghanistan. “Will the rest of the Taliban join him as declared enemies of America?” I asked.

Osmani saw where this was going, and jumped ahead: “You won’t be able to replace the Taliban with oppositionists,” he told me.

“Look,” I countered, “only Afghans can make a permanent solution for Afghanistan. The United States will be able to chase the terrorists away, but without a responsible Afghan government, they can come back. If the Taliban is willing to be that government, this will be acceptable to us; but if not, war will inevitably come. ... No one knows how it will turn out. All that is sure is that it will be a disaster for Afghanistan, and the end of the Taliban.”

The outsized mullah began waving his hands as he launched into a long string of excuses. “Bin Laden,” he said, “has become synonymous in Afghanistan with Islam. The Taliban can’t hand him over publicly any more than they can publicly reject Islam. Neither Omar nor the rest of the shura like the Arabs”—that is, al-Qaeda— “[and] they want to cooperate with America, they do, but public threats from the United States have aroused the people and boxed the leadership in politically. Besides,” he complained, “Omar has made a public commitment to bin Laden; he can’t simply renounce it now. He would like to be rid of this man, but his hands are tied. In fact, Omar sent a messenger to bin Laden five days ago; he reminded Osama of the [religious council’s] decision that he should leave the country. ‘You must deal with them,’ the messenger told him.”

Osmani then made an offer. “I can track Osama down and kill him if you like,” he said. “But I can’t use my own troops. That would be too public; my role would be known. For that, I have to find outside operatives. This will take time.”

I shook my head: It wouldn’t work. “Washington will see this as a delaying tactic,” I told him. “They might have listened to this months ago, before 9/11, but it’s too late now. The United States is preparing for all-out war as we speak. If you want a risk-free solution, you won’t find it. If you want to save the Taliban and your country, you’re going to have to take risks.”

Osmani’s voice took on a desperate tone: “Your threats have created big problems for us. Afghans are reacting emotionally...” His voice trailed away.

“If threats have been made, they can’t be unmade,” I broke in. “There’s no point in trying to change the past. The point is to find a way to save Afghanistan.”

Osmani paused, and slumped lower in his chair. He suddenly looked very tired, played out. There was nothing left to say. He removed his turban, and put it aside. Looking down, he said: “Then you suggest a solution.”

This was the opportunity I’d hoped for.

Years before, while planning a potential military coup in Baghdad, I had read Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook, by Edward Luttwak. In it, Luttwak lists the sequential steps that traditionally must occur for a coup to succeed. I could see them as a checklist in my mind as I spoke.

“Mullah Sa’eb,” I began, using Osmani’s Taliban nickname. “You are the second-ranking member of the Taliban. You are widely respected; you have great power and influence. You command the Taliban forces in and around [the southern city of] Kandahar. only you can save your country. Omar, by your own admission, is bound by his pledge to Osama. He will fall as a result, and he will take the Taliban with him. But you are not bound by such a pledge, nor are the other members of the shura. You can take the actions necessary.”

“First,” I said, beginning to lay out the steps, “you must rally your troops and seize control of all key government buildings in Kandahar, as well as the principal roads and intersections. Anyone in a position to resist you must be placed in detention. First among them must be Mullah Omar. No one is suggesting he should be harmed, but he cannot be allowed to communicate with anyone. Your most important objective,” I went on, “is to seize Radio Shariat, the voice of the Taliban, and to make an immediate announcement.” I told him that he must tell Afghans he was acting at the direction of Afghanistan’s religious leaders who, after all, had put Omar in power in the first place. “He has refused their direction, and now you are forced to seize power to obey their dictates,” I said. “You must declare that the Arabs are no longer welcome, and demand the departure of al-Qaeda from Afghanistan.”

“Immediately thereafter,” I continued, getting to the main point, “you must move against bin Laden. He and those around him will resist violently, and will have to be killed. No one will have to know that you have done this; [al-Qaeda has] many enemies. The other Arab fighters, having heard your decree and learned that bin Laden is dead, will get the message: They will flee.” I told him that bin Laden’s 14 top lieutenants must be captured quietly and given to us, but that no one need know how they ended up in American custody. “With so many Arabs fleeing,” I pointed out, “many will assume that they were captured in neighboring countries.”

“This,” I said, “is your opportunity to save your country.”

I added one final point: “You should know that we can give you anything you need to get this done.” The implication, which the mullah clearly understood, was that I was prepared to give him large sums of money.

“I won’t need any assistance,” he replied.

The commander began to mull over what I’d said, reacting aloud. He had no problem taking the quiet actions we demanded against bin Laden and the 14 others. But why did he have to make a public announcement expelling the Arabs?

I explained that the change in Taliban policy to deny safe haven to al-Qaeda would have to be announced publicly to be effective. Any specific actions they took to implement their policy and to meet our demands, however, could be kept secret, so long as we could see the results.

My promises of secrecy were not quite as ridiculous as they might appear now. Afghanistan at that point had no cell-phone system, no international phone service of any kind outside of a handful of government-controlled lines into Pakistan, and no independent media. The country was nearly opaque to the outside world.

“All right,” he said. “But if we change our policy on bin Laden and al-Qaeda, why can we not let the other Arabs remain as refugees?”

I was becoming exasperated. “Why do you want to invite trouble from the whole world for the sake of a handful of Arabs? ... [W]hy don’t you concern yourself with the millions of Afghans who have been refugees for years?” Osmani laughed, and shook his head slowly.

“You are right,” he said.

I warmed to the subject. “Look,” I said. “We realize we made a big mistake when we abandoned Afghanistan after the Soviets left. We will not make this mistake again. For a friendly Afghan government willing to oppose the terrorists, the United States will provide massive humanitarian relief. We will assist the Afghan refugees to return to their homes.” I was not entirely making this up. A few days before, Condoleezza Rice, during the course of several hours of briefings on Afghanistan, had asserted that the U.S. would remain engaged in Afghanistan for the long term.

By now, Osmani was grinning and nodding. “This is very good,” he said. “I will bring your proposal to Omar.”

I nearly fell out of my chair. This was not where I was going at all: The proposed actions had been for Osmani, not Omar. Still, I thought, reflecting quickly, in the unlikely event that Omar agreed and actually followed through, it would be all the same to us. But, I said, fixing my friend with a stare, if Omar should refuse this proposal, as in all likelihood he would, it was up to Osmani to step in, seize power, and do it himself.

The mullah looked at me with apparent resolve. “I will do it,” he said.

Osmani suddenly seemed buoyed and happy. He rose to his feet and folded me in a Pashtun man-hug, left arm over my right shoulder, right arm gripping me about the waist. I gave him a satellite phone, and we agreed on time windows when we would be available to speak. At his suggestion, we ripped a pair of Pakistani bank notes, each taking half: These would serve as bona fides if either of us were to send an emissary to the other. Afterwards, we fairly marched together out the door and down the hall, where we were joined by another Taliban official and our ISI host, who had arranged a huge lunch of mutton and rice.

Despite the volume of food, such lunches are usually quick affairs, with little conversation. I watched closely as Osmani ate happily and with great gusto. When we had finished, he got to his feet. Abdul Salam Zaeef, the Taliban ambassador to Pakistan, would be flying down from Islamabad later that day. Osmani would remain in Quetta to receive him, and then travel with him by road to Kandahar the following morning, October 3. Again I pressed Osmani to respond to me quickly, on October 4 if at all possible. Again the burly man embraced me as though I were a long-lost brother, and turned to leave.

* * *

“Ref[erenced] cable received a mixed response at Headquarters,” the response began. It was October 4, and I had sent to my CIA superiors a 10-page report on my three-hour conversation with Mullah Osmani. The answer I got was rather more positive than I had expected. It went on to state that if the Taliban leadership responded positively to my overtures, headquarters would be prepared to put their proposal on the table for policy consideration. The tone of the message made it clear that no one in the policy world would welcome having to decide in such ambiguous circumstances.

More than 13 years later, it is a little hard to sympathize with those concerns.

Mullah Osmani called me on October 6. As translated by Tom, he told me he’d met with Mullah Omar, who had a message to convey. Omar would make some announcements soon, but he could not make the announcement we had demanded of him right away, as he would have to calm the Afghan people first due to the American threats.

“There is no time for this,” I told him. “Omar will not carry out the demands; Afghanistan will be destroyed. It’s up to you to seize power, as we discussed.”

There was a long pause. He finally agreed to call me by noon the following day—October 7.

That day, I knew, was when the first American strikes would be launched. The day passed without the promised call. Late that night, Afghan time, the first aircraft and cruise missiles struck their targets in and around Kabul and Kandahar.

This post has been adapted from Robert L. Grenier's new book 88 Days to Kandahar: A CIA Diary.

'美國, 韓美關係' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Why Americans Don’t Read Foreign Fiction (0) | 2015.10.18 |

|---|---|

| America Should Send More People to Prison (0) | 2015.10.18 |

| Why a Generation of Adoptees Is Returning to South Korea - NYT Magazine (0) | 2015.10.18 |

| 米国最大の債権国は? 中日の上位独占が続く (0) | 2015.10.18 |

| The invasion of America (0) | 2015.10.18 |