-

21 January 2015

- From the section Business

The BBC's new A Richer World season is exploring global wealth, poverty and inequality. But what exactly does a richer world mean?

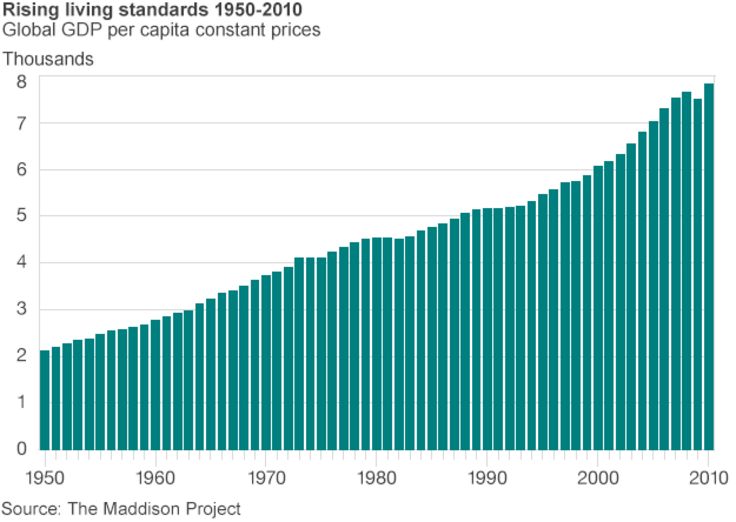

We are getting richer. Not every human being on the planet and not every country. But the average person has an economic standard of living that's far better than it used to be.

One way of measuring it is to look at the amount of goods and services produced per person - gross domestic product or GDP per capita.

For the global population that rose almost fourfold in the 60 years up to 2010.

There were some marked divergences between countries. In China the increase was a stunning eighteen-fold. South Korea and Taiwan managed even more. on average, they are 25 times richer than in 1950.

A few countries, mainly in Africa, lost ground. In the Democratic Republic of Congo average living standards fell by more than half in the same period.

These figures do need some health warnings. They don't capture intangible things that affect the quality of life, such as the strength of communities or environmental standards. There are also some technical issues about comparing everything in dollars and adjusting for inflation, to get a "real terms" comparison, over a long period.

But they are taken from what is probably the most highly regarded source for historical economic data, a project established by the late Prof Angus Maddison. And the story they tell is clear. In economic terms we are better off.

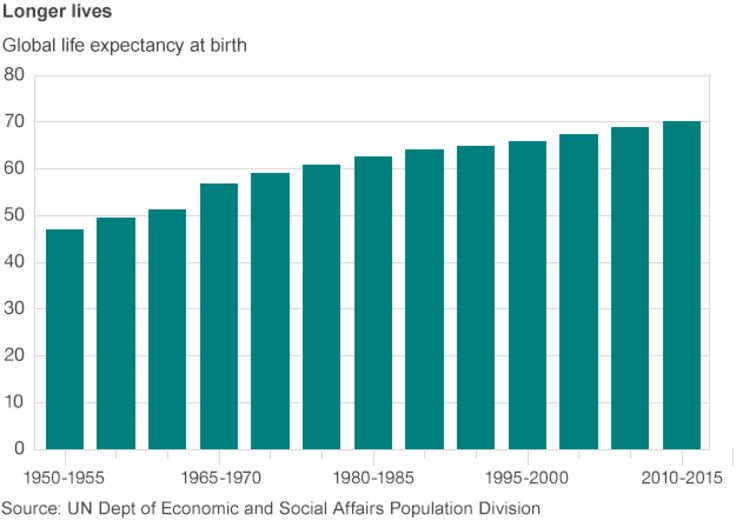

One benefit from that is that we are living longer. In the middle of the last century a new-born baby could expect to live 50 years. Now the figure is 70. once again there are large variations between countries but the favourable trend in that period is present in almost every nation - Botswana is the only one where life expectancy declined (by a few months).

There are many factors behind longer lives, but economic growth means we can spend more on our health, on nutrition and on ensuring that we have safe clean water to drink.

Car ownership

We get a similar story of rising living standards if we zoom in a little more closely. Car ownership increased by 30% in the first seven yars of the century before dipping a little in the global recession. The increase was especially marked in middle and low income countries.

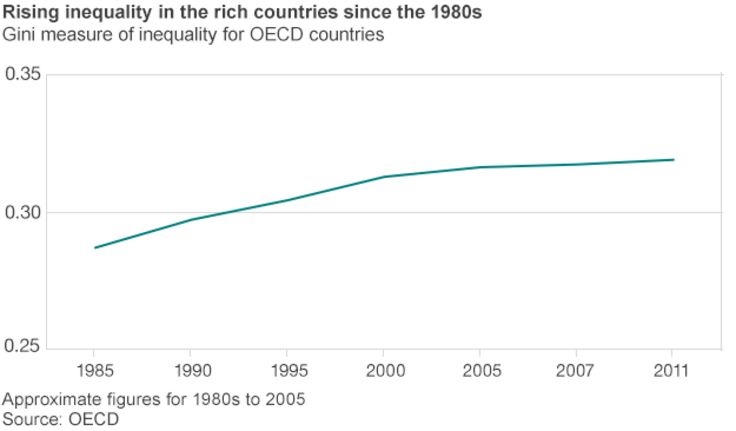

Turning back to those admittedly rather rough and ready average figures for living standards, GDP per capita, there's another reason they don't tell the whole story. They tell us nothing about the distribution of income, or about changing patterns of inequality.

You can have rising average standards of living if the people with the highest incomes get richer, even if others don't.

Take the United States (because there is a lot of data available). In 2013, the real (inflation adjusted) income for a household 20% from the bottom of the income distribution (technically, at the first quintile) had risen by 1.4% over the previous 40 years. For a rich household (the 95th percentile) the figure was 44%.

Figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) also point to rising inequality among its member countries, which are the rich nations and some of the leading emerging economies. The graph uses a measure called the Gini coefficient. The larger the number, the more unequal the distribution of income - and it has risen in recent years.

There is of course a debate, a rather vigorous one, to be had about just how bad a thing rising inequality really is. That is even more true of the question of what, if any, government policies should be employed to tackle it.

Rising inequality is a reminder that, richer though the world is, some people don't feel it.

For more from the BBC's A Richer World season, click here