William Shakespeare has been dead for 401 years. While this would be enough to keep most people out of the news, the Bard has a way of insinuating himself into just about everything. He plays the lead in political controversies. People recast his life as a television show filled with 16th-century rap battles. His works get molded around whatever genre is currently in vogue: The Taming of the Shrew as a ’90s teen romp; Hamlet as a lion-based animated musical.

When Angus Vail—a music and art space manager—thinks about revitalizing Shakespeare, though, he doesn’t focus on the “who” or the “what” so much as the “where.” The soul of those immortal plays, Vail thinks, is best expressed in the first environment where they were ever shown: an open-air theater, where you can get rained, spat, or spilled on, and the audience and the players are practically close enough to touch.

His current project, the Container Globe, aims to bring back this age-old theatrical experience, but using a material and location Shakespeare likely wouldn’t recognize: a bunch of recycled shipping containers, stacked on top of each other in an empty lot in Detroit.

Like most people, Vail was introduced to Shakespeare sometime around middle school, when his teacher had the class listen to Antony and Cleopatra on a vinyl record. “I was bored to tears,” he says. He didn’t really get into it until years later, in the 1980s, when he was living in London and began frequenting the Royal Shakespeare Company’s standby line. “You’d pay five quid, and go in and see Jeremy Irons, or Anthony Hopkins,” Vail says. “I became a bit of a Shakespeare geek.”

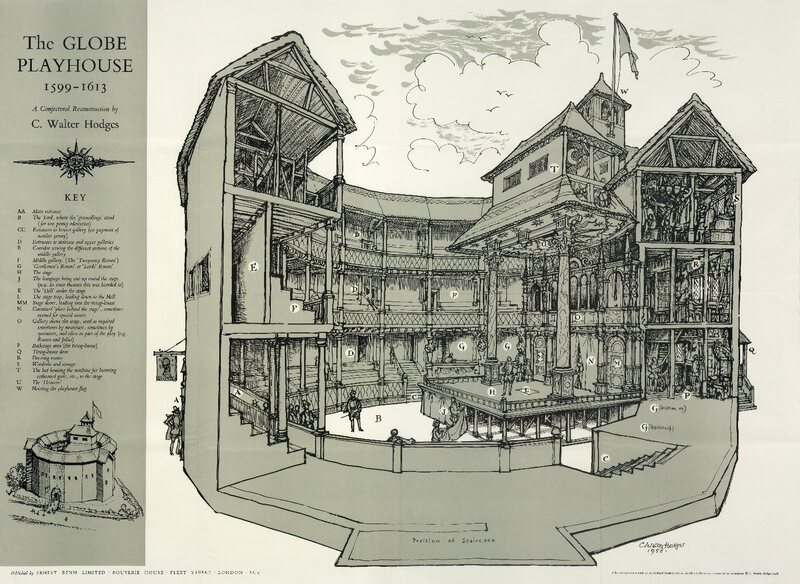

After 1997, he switched his patronage to London’s newly opened Globe: a scaled-down reconstruction of the original Globe Theater, where many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered, and where his theatrical company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, kept residence. The new Globe, like the old, is open-air, with little separation between the players and the audience, or between both and the outside world. A pigeon, Vail says, once strutted and fretted across the stage right in time with Macbeth’s Act V soliloquy. A real storm sometimes cameos in The Tempest.

Something clicked. “Seeing Shakespeare in the Globe is really different,” he says. “You don’t do Hamlet standing on a stage, going ‘To be or not to be?’ out into the darkness … the audience becomes almost part of the action.” A high-energy show at the new Globe might have 600 people right up near the stage, drinking beer and guffawing at the actors, not unlike the 17th-century “groundlings” who paid a penny to stand in the yard of the original theater and shout during the swordfights.

“It becomes chaotic,” Vail says. “More alive, more interactive, more visceral, more kick-in-the-balls. I was saying, ‘Holy shit! This is like punk rock.’ You’ll never see the same performance twice.”

Around 2012, this parallel inspired Vail—who loves punk almost as much as he does Shakespeare—to start working on bringing a Globe-style theater to the United States. (The punk thing has also trickled heavily into the branding efforts. When Vail gave a TEDx Talk about the Container Globe last year, he wore a Ramones-esque t-shirt, with the band member’s names replaced by “HAMLET,” “LEAR,” “MACBETH,” and “OTHELLO.”) He’s chosen a spot in Detroit’s Highland Park, citing the city’s industrial history, economic recovery efforts, and current artistic renaissance.

Vail knows that neither of his goals—to make Shakespeare relevant to the modern era, and to build a public space out of shipping containers—is particularly unique. But the combination, he insists, is less zeitgeisty than it is serendipitous. The stage of the original Globe theater was 42 feet long, and a standard large shipping container is 40 feet.

Meanwhile, a smaller shipping container is 20 feet long, the right size for a seating gallery. Because the dimensions work out, building the theater simply involves arranging larger and smaller containers in various stacks, like building blocks. “It just happened to work out that way,” Vail says. “The container gods have deemed it so.”

Right now, the project team is in the process of fabricating the containers. Actual building will commence this spring, followed, hopefully, by the first performances. As planning and prototyping continues, he says, other coincidences have emerged: the corrugated surfaces of the containers, it turns out, are good at both reflecting and diffusing sound, enviable acoustic properties for a theater. The original Globe was built with timber rescued from another theater; the Container Globe will incorporate used containers, transformed for their new lives by local artist Ferrous Wolf.

Containers also offer some advantages that the original and new Globes lack, Vail says. Compared to other building materials, they’re are fairly inexpensive, savings that the theater can then pass on to customers. (The cheapest seats will be, of course, right up in the front.) Their modularity allows for physical reconfiguration and portability, something Vail hopes to explore if, as he plans, he ends up building more Container Globes in more cities.

Their aesthetic also strikes him as more neutral, allowing for various types of performance. “We can have it lit one way and it’ll be a crazy Thunderdome, like Mad Max,” he says. “We can light it another way and have it look much more classical.” Other theaters, he says, are less chameleonic: “It’s very hard to do a death metal show in a wooden Globe.” Perhaps that’s reason enough to build a new one.