Around the lake in Starnberg, some 50 kilometers from Munich, the successive rows of Alpine chalets are interrupted by a single white building with huge windows – the architectural equivalent of rationalism in the land of Heidi, a juxtaposition of Bauhaus modernism and Bavaria’s staunch conservatism. A small white plaque on a blue door confirms that this is the home of the Düsseldorf-born thinker Jürgen Habermas, whose prodigious output – even as he approaches his 89th birthday – has earned him a hallowed place among the world’s most influential philosophers.

His wife of more than 60 years, historian Ute Wessselhoeft, opens the door to reveal a small hallway and calls her husband: “Jürgen! The men from Spain are here!” Ute and Jürgen have lived in this house since 1971, when the philosopher assumed the direction of the Max Planck Institute.

A disciple and assistant to Theodor Adorno, a distinguished member of the Frankfurt School’s so-called second generation and Professor of Philosophy at the Goethe University Frankfurt, Habermas emerges from the slightly chaotic den of papers and books he calls his study, whose windows look out on to the forest.

You can’t have committed intellectuals if you don’t have the readers to address ideas to

The room is decorated in white and ocher, and there’s a small collection of modern art that includes paintings by Hans Hartung, Eduardo Chillida, Sean Scully and Günter Fruhtrunk as well as sculptures by Jorge Oteiza and Joan Miró – this last one as a prize for the Prince of Asturias Award for Social Sciences, which he received in 2003. The bookshelves contain volumes by Goethe and Hölderlin, Schiller and Von Kleist, and rows of works by Engels, Marx, Joyce, Broch, Walser, Hermann Hesse and Günter Grass.

Himself the author of important works concerning sociological and political science in the 20th century, Habermas talks to EL PAÍS about the issues that have concerned him for the last 60 years. His posture is rigid, his handshake firm and, despite his grandfatherly aspect emphasized by a mane of white hair, he is angry. “Yes,” he says. “I’m still angry about some of the things that are happening in the world. That’s not a bad thing, is it?”

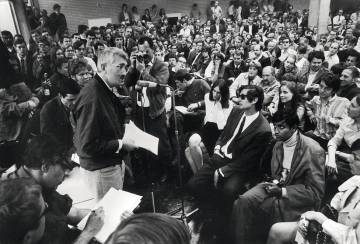

Habermas has difficulty articulating due to a cleft palate. But it was his struggle with speech that prompted him to think more deeply about communication, which he sees as a means of curing at last a portion of society’s ills. The old professor seems resigned when, at one point, looking out of the window during our conversation, he murmurs, “I don’t like big auditoriums or rooms anymore. I don’t know what’s going on. There’s a cacophony that fills me with despair.”

Question. There is a lot of talk about the decadence of the committed intellectual. But do you think it’s fair to say that this topic of conversation rarely goes beyond the intellectual sphere?

Answer. Based on the French model – from Zola to Sartre and Bourdieu, the public sphere is crucial to the intellectual, though its fragile structure is undergoing an accelerated process of decay. The nostalgic question, ‘Where have all the intellectuals gone?’ misses the point. You can’t have committed intellectuals if you don’t have the readers to address the ideas to.

Q. Has the internet diluted the public sphere that supported the traditional media, which has, in turn, adversely affected philosophers and thinkers?

A. Yes. Since Heinrich Heine, the figure of the intellectual has gained in status along with the classical configuration of the liberal public sphere. However, that depends on implausible social and cultural assumptions, mainly the existence of alert journalism, with newspapers of reference and mass media capable of directing the interest of the majority toward topics that are relevant to the formation of political opinion; and also the existence of a reading population that is interested in politics, educated, accustomed to the conflictive process of forming opinions, and which takes the time to read quality, independent press.

The only way to deal with waves of immigration would be to tackle the economic causes

Nowadays, this infrastructure is no longer intact, although as far as I know it still exists in countries such as Spain, France and Germany. But even there, the splintering effect of internet has changed the role of traditional media, particularly for the younger generations. Even before the centrifugal and atomic tendencies of the new media came into force, the commercialization of public attention had already triggered the disintegration of the public sphere. An example is the US and its exclusive use of private TV channels. Now, new means of communication have a much more insidious model of commercialization in which the goal is not explicitly the consumer’s attention, but the economic exploitation of the user’s private profile. They rob customers’ personal data without their knowledge in order to manipulate them more effectively, at times even with perverse political ends, as in the recent Facebook scandal.

Q. Despite its obvious advantages, do you think the internet is encouraging a new kind of illiteracy?

A. You mean the aggressive controversies, the bubbles and Donald Trump’s lies in his tweets? You can’t even say that this individual is below the political cultural level of his country. Trump is permanently destroying that level. From the time the printed page was invented, turning everyone into a potential reader, it took centuries until the entire population could read. Internet is turning us all into potential authors and it’s only a couple of decades old. Perhaps with time we will learn to manage the social networks in a civilized manner. Internet has already opened up millions of useful niches of subcultures where trustworthy information and sound opinions are being exchanged. – not just the scientific blogs whose academic work is amplified by this means, but also, for example, [forums] for patients who suffer a rare disease and can now get in touch with others in the same situation on another continent to share advice and experience. There are undoubtedly great communication benefits and not just for increasing the speed of stock trading and speculation. I am too old to judge the cultural impulse that the new media is giving birth to. But it annoys me that it’s the first media revolution in the history of mankind to first and foremost serve economic as opposed to cultural ends.

Q. In the technology-dominated landscape of today, what is the future for philosophy?

A. I am of the antiquated opinion that philosophy should continue to try answering the questions of Kant: What can I know? What should I know? What can I expect? What is it to be human? However, I’m not sure that philosophy as we know it has a future. Currently, it follows the trend of increasing specialization, like all disciplines. And that’s a dead-end street because philosophy should try to explain the whole, to contribute to the rational explanation of our way of understanding ourselves and the world.

Q. What has become of your old affiliation to Marxism? Are you still a leftist?

A. I have spent 65 years working and fighting for left-wing postulates at universities and in the public sphere. If I have spent a quarter of a century fighting for greater political integration of the European Union, I do it with the idea that only this continental organization is capable of bringing unfettered capitalism under control. I’ve never ceased to criticize capitalism but nor have I ceased to be aware that offhand diagnosis is not enough. I’m not one of those intellectuals who shoot without aim.

Q. Kant + Hegel + Enlightenment + disenchanted Marxism = Habermas. Is that right?

A. If you have to express it telegraphically, then yes, although not without a pinch of Adorno’s negative dialectic.

Q. In 1986, you came up with the political concept of constitutional patriotism, which sounds almost medicinal today in the face of other supposed patriotisms that involve anthems and flags. Would you say it’s far harder to achieve the former?

A. In 1984, I was invited to give a talk in the Spanish Congress. Afterwards we went to eat at a long-established restaurant. If I remember rightly, it was between Congress and the Puerta del Sol, on the left side of the road. During the animated conversation with our illustrious hosts, many of whom were social democrats who had been involved in the drafting of the country’s new constitution, my wife and I were told that it was in this establishment that the conspiracy for the declaration of the First Republic of Spain had taken place in 1873. As soon as we knew this, we had a totally different feeling. Constitutional patriotism needs an appropriate backstory so that we are always aware that the Constitution is a national achievement.

Q. Do you consider yourself a patriot?

A. I feel like a patriot of a country which, at last, after the Second World War, gave birth to a stable democracy and, over subsequent decades of political polarization, a liberal political culture. It’s the first time I have said as much but in that sense, yes, I am a German patriot as well as a product of German culture.

Q. With the influx of migrants, does Germany still have just one culture?

A. I am proud of our culture that includes second or third-generation Turkish, Iranian and Greek immigrants, who produce amazing filmmakers, journalists and TV personalities as well as CEOs, the most competent doctors, the best writers, politicians, musicians and teachers. It’s a palpable demonstration of our culture’s strength and capacity for regeneration. The right-wing populist aggressive rejection of these people, without whom it would be impossible, is nonsense.

I respect Macron because he dares to have political perspective and courage

Q. Can you tell us something about your new book on religion and its symbolic strength as a remedy to certain modern-day ills?

A. It’s not so much about religion as philosophy. I hope that the genealogy of post-metaphysical thought based on an age-old argument about faith and knowledge can go some way towards preventing a progressively degraded philosophy on the scientific front from forgetting its function to enlighten.

Q. Speaking of religion and of religious and cultural wars, do you think we are heading for a clash of civilizations?

A. As far as I’m concerned, that idea is totally erroneous. The oldest and most influential civilizations were characterized by the metaphysics and great religions studied by Max Weber. All of them have a universal potential, which is why they thrive on openness and inclusion. The fact is that religious fundamentalism is a totally modern phenomenon. It grew out of the social uprooting triggered by colonialism, the end of colonialism and global capitalism.

Q. You have written on occasion that Europe should nurture a European version of Islam. Do you think that’s already happening?

A. In the Federal Republic of Germany, we make an effort to include Islamic theology in our universities, which means we can train teachers of religion in our own country instead of importing them from Turkey and other places. But really this process depends on us managing to truly integrate immigrant families. However, this doesn’t address the waves of global migration. The only way to deal with that would be to tackle its economic causes in the countries of origin.

Q. How do you do that?

A. Without making changes to the global capitalist system, don’t ask me. It’s a problem that goes back centuries. I’m no expert but if you read Stephan Lessenich’s Die Externalisierungsgesellschaft [The Externalization Society], you’ll see how the origin of these waves washing over Europe and the Western world have their origins within it.

Q. You are quoted as saying that Europe is an economic giant and a political dwarf. Nothing seems to have improved – we’ve had Brexit, populism, extremism and nationalism.

A. The introduction of the euro divided the monetary community into north and south – the winners and the losers. The reason for this is that the structural differences between the national economic regions can’t compensate for each other if there is no progress toward a political union. The escape valves, such as mobility in a single labor market and a common social security system, are missing. Europe also lacks the power to come up with a common fiscal policy. Add to this a neoliberal political model incorporated into European treaties that reinforce the dependency of the nation states on the global market. The rate of youth employment in southern countries is scandalous. Inequality has increased across the board and eaten away at social cohesion. Among those who have managed to adapt, the liberal economic model has taken hold, which promotes individual gain. Among those in a precarious situation, regressive tendencies and reactions of irrational and self-destructive anger are spreading.

Q. What do you think of the independence issue in Catalonia?

A. I don’t understand why an advanced and cultured population like Catalonia wants to go it alone in Europe. I get the feeling it is all about economics. I don’t know what will happen. What do you think?

Q. I think that politically isolating a population of around two million people with aspirations to be independent is not realistic. And not easy.

A. It’s a clearly a problem.

Q. Do you consider nation states to be more necessary than ever?

A. Maybe I shouldn’t say this but I believe that nation states were something that nobody believed in but which had to be invented when they were, for eminently pragmatic reasons.

Q. We are always blaming politicians for the problems with the construction of Europe, but perhaps the public is also guilty of a lack of faith?

A. Up to now, political leaders and governments have taken the project forward in an elitist manner without including the people in the complex questions. I have the feeling that not even the political parties or national MPs are familiar with the complicated material that constitutes European politics. Under the slogan, ‘Mother looks after your money,’ Merkel and Schäuble have shielded their measures during the crisis from the public sphere in a truly exemplary manner.

Q. Has Germany at times mistaken leadership for hegemony? And where does that leave France?

A. The problem has surely been that the Federal Government of Germany has had neither the talent nor the experience of a hegemonic power. If it had, it would have known that it is not possible to keep Europe together without taking into account the interests of the other states. In the last two decades, the Federal Republic has acted increasingly as a nationalist power when it comes to economics. With regard to Macron, he continues to try to convince Merkel that she has to think how she will look in the history books.

Q. What is Spain’s role in the construction of Europe?

A. Spain simply has to support Macron.

Q. Macron is a philosopher like you. Do you think politics and philosophy work well together?

A. For God’s sake, spare us governing philosophers! However, Macron inspires respect because in the current political landscape, he’s the only one who dares to have a political perspective; who, as an intellectual and a convincing orator, pursues the political targets set out by Europe; who, in the almost desperate circumstances of the elections, showed personal courage and, until now as president, has done what he said he would. And in an era characterized by a paralyzing loss of political identity, I have learned to appreciate these personal qualities despite my Marxist convictions.

Q. However, it is impossible to know yet what his ideology is, or if he even has one.

A. You’re right. I still can’t see what convictions lie behind the French President’s European politics. I would like to know if he is at least a convinced left-leaning liberal, which is what I hope.

The guardian of conversation

Daniel Innerarity

Three guests sit down to eat in the Habermas home and immediately the room is abuzz with conversation. Far from dominating, Jürgen Habermas listens and inquires, undoubtedly the hallmark of a great thinker. There is a sense that we are perhaps speaking to the last of the public intellectuals, who commanded the kind of authority that we are starting to miss in this age of social media and opportunistic immediacy. I would venture to say that Habermas’ legacy will be not so much his vast written contribution but his appreciation of the public sphere, which is more of a civic virtue and an intellectual attitude than a theory. Habermas is, above all, an enthusiast when it comes to conversation; someone convinced of the value of shared effort. His fundamental concern has always been to protect and improve this inter-subjective space because that’s where we make real discoveries and, above all, where we build democratic harmony.

A product of the classical German philosophical tradition against which he has tested other more modern theories such as analytical language or republican forms of democracy, Habermas is equipped with a broad culture that is not so much the amassing of information as the versatility of an internal dialogue. Evident in his ideas are Kant, Marx and Adorno, not as speechless museum pieces but as active participants who could dialogue with Austin, Derrida and Rawls. The end result is a conversation between many participants. This taste for general interpretations of the world and its culture is something that seems almost foreign in an era of fragmentation and specialization. His main obstacle is the skepticism practiced by people who think it either impossible or at least less worthwhile than knowing everything about almost nothing. Habermas has always resisted the accusation of arrogance or naiveté for considering the whole. Thanks to his courage, the idea of putting human beings and dialogue at the center of all solutions is familiar to us all.

Perhaps this passion for public dialogue explains the sense of responsibility that has dominated his life as a public intellectual. His job as professor and researcher are inseparable from his continuous contributions to the great debates of our time, whether they be the public use of history, the risks of genetic engineering or, more recently, the way in which Europe should resolve its crisis. If Voltaire said about our responsibilities that we should tend to our own gardens, in a similar vein, Habermas seems to be saying we should nurture our conversations. According to his view, the public sphere should not be conceived of as a huge and solemn debate between the world’s most powerful figures, but also a conversation around the dinner table during which we may not all always agree.

English version by Heather Galloway.