God, the Editor

Can the Qur’an be read as literature?

Who was God speaking to when he said “Let there be light”? There was nobody to hear him, no spouse, no servants, not even a “mythic animal,” wrote Jack Miles in God: A Biography, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1996. God was “as yet unmade by any history.” He needed an interlocutor: when he shaped an image of himself in clay, God grew as dependent on his creation as it was on him. “Where are you?” God called out to Adam and Eve as he strolled in the garden.

An agnostic, ex-Jesuit book critic and professor of religion, Miles, in a new mode of biblical literalism, read the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, from beginning to end to see how God’s character developed over the narrative. Just as one might study the character of Hamlet in Shakespeare, Miles aspired to meet God as the protagonist of a great literary classic. If it sounds anthropomorphizing, it was—yet Miles, who trained in Near Eastern languages at Harvard, the Hebrew University, and the Pontifical Gregorian University, strove to be faithful to what is there on the page. In the 1980s and 1990s, a constellation of critics were reading the Bible as literature—Northrop Frye, Harold Bloom, Frank Kermode, and Robert Alter among them—at an intellectual moment when both God and the author were considered dead. Miles’s elegantly simple idea to write a “theography,” a word not enshrined in dictionaries, felt revelatory and new. In 2001, he followed this success with Christ: A Crisis in the Life of God, a reading of God’s continuing biography in the New Testament, and he has now completed a trilogy of the monotheisms with God in the Qur’an. Seeking to understand the character of the divine protagonist as it changes over the course of the three scriptures, Miles begins from the premise that the deity of Judaism and Christianity is the same God of Islam, the same celestial presiding over the three Abrahamic faiths. In his final installment, Miles shows how the Qur’anic God revises and corrects his earlier portrayal, an endeavor in line with the common Muslim view that Islam is the perfection of the three monotheisms: the newest and best version. Yet this also means that, with the conclusion of Miles’s series, God demands edits on the story as the theographer has told it so far.

What emerged in God: A Biography was a deity riven with contradictions, an Almighty who seemed, terrifyingly, to act first and think after. Theography, it turned out, was like a kind of divine psychoanalysis. one could picture Miles as therapist, his patient reclining on a sofa made from clouds. God told humankind to be fruitful and multiply, yet he swiftly became full of rage and regret at how we proliferated unchecked. He drowned his creation, only to regret it. When the survivors of the flood offered him grilled meat, “the Lord smelled the pleasing smell and said to himself, ‘Never again will I curse the earth because of human beings,’” as the enigmatic voice that seems to know the creator’s inner thoughts narrates in Genesis. Drawn into battle on behalf of the Israelites in Pharaoh’s Egypt, God was transformed by war. He became a violent extremist, Miles wrote, butchering his chosen people and “terrorizing the very sky.” In Exodus, God became more interested in law and order; he gave Moses the Commandments and defined himself by his justice. Yet by the Book of Numbers, God and the Israelites, bound together in the covenant, had begun to complain about each other incessantly. God was irritable, “impossible to please,” as Miles put it, and so were the Israelites, made as they had been in his image.

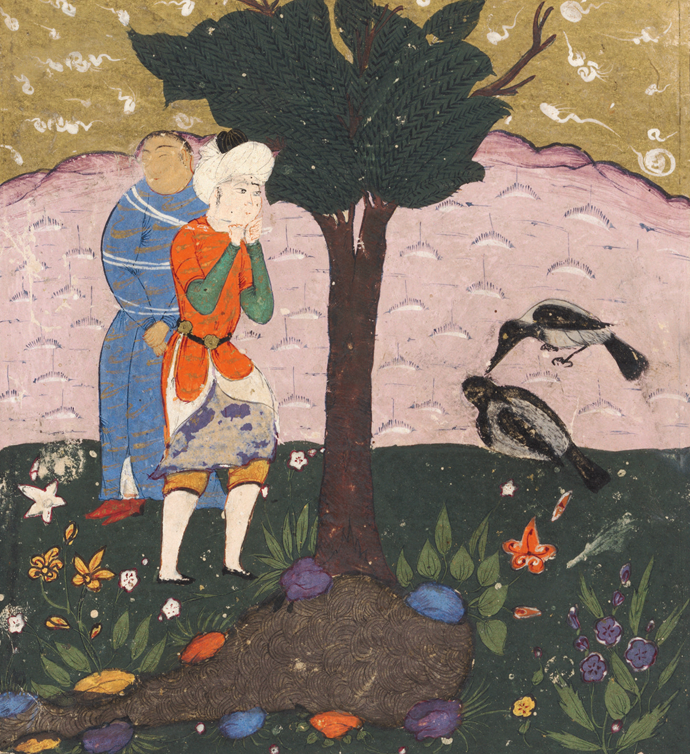

Crow Teaching Qabil (Cain) How to Bury His Brother, from Qisas al-Anbiya (Tales of the Prophets) of Ishaq b. Ibrahim al-Nayshaburi

© Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, The Edwin Binney, 3rd Collection of Turkish Art at the Harvard Art Museums

In historical scholarship, the inconsistencies in God’s behavior as it is portrayed in the Bible are often explained as traces of the multiple authors behind the texts. For theography, the contradictions are instead evidence of what Miles called divine inner conflict. As polytheism gave way to monotheism, the one accrued the personalities of the gods he encompassed: from benevolent Mesopotamian deities, to the Canaanite warrior Baal, to Tiamat, the serpent of chaos. The same bipolar God would have to create and destroy—raising, for the first time, the problem of evil that the innocent, suffering Job so pitifully invokes. For Miles, monotheism became “the story of a single God struggling with himself,” the divided image we are condemned to replicate in our daily lives. With the fall of Jerusalem and the exile of Israel to Babylon, Miles wrote, God seemed to enter a crisis. The Israelites were violating the covenant he had made with Abraham; God’s forgiveness seemed to undermine his authority. Worse, it began to appear as though many of God’s prophecies had not come to pass. It was then that God first began to maintain his inscrutability, insisting, in the Book of Isaiah, on what Miles described as “mystery rather than power as the source of his holiness.” After appearing to lose a bet with Satan, God thunders at Job in the whirlwind, but after that, he never again speaks in the Tanakh. In Miles’s reading, Job reduced God to silence.

Trapped within his own contradictions, God devised an astonishing way out, according to the second book, Christ, which was published only a few weeks after 9/11. Empires have come and gone, and yet Israel is still under subjugation, now by the Romans. If the omnipotent God cannot liberate his chosen people, nor claim that oppression is his will, “then he must admit defeat,” Miles wrote. “On the terms by which, starting at his victory over Pharaoh, he himself has defined his divinity, he has failed.” But God, after all, has the power to redefine the terms: if he cannot beat the enemy, “God may declare that he has no enemies,” that he loves all men equally, and urge men to do the same. This is easy for God to do, surrounded by well-behaved cherubim, yet less so for man—and so God descends to earth in human form to show us the way. In Christ, Miles portrayed Jesus not as a historical rebel but as the Tanakh’s God incarnate, and read the New Testament as his continuing biography. For a minor disobedience involving a certain fruit, God had cursed his creation and invited death into the world. Arriving in the body of a Nazarene peasant, with a pacifist temperament so different from his usual self, God will, in the words of St. Paul, reconcile the world to himself. He will defeat man’s true enemy, not other men but Satan—death itself. In Christ, Miles captured anew the strangeness of a suicidal god, determined to go to earth to kill himself.

God, in other words, disarmed himself; the deity who hungered for meat became the sacrificial lamb. The lawgiver became a criminal, taking on the crown of king of the Jews when he knew that, under Roman law, to usurp sovereignty was a capital offense. When, after three nights in the tomb, Jesus triumphed over death, it was a double redemption for both “human hope and divine honor,” Miles wrote. According to the Gospel of Luke, the risen Christ encountered two men along the road and narrated to them his story. “Starting with Moses and going through all the prophets, he explained to them the passages throughout the scriptures that were about himself.” In his resurrected cadaver, God embarked upon his own project of autotheography.

In the final book of Miles’s trinity, God essentially informs the theographer that he has gotten much of the story wrong. Retreating from the magisterial scope of his earlier work, in God in the Qur’an Miles does not strive to elucidate the Islamic scriptures from start to finish but rather to present a “modest” comparison of material shared between the Qur’an and the Bible.* While Yahweh began as a character without a history, Allah is here a deity with a deep past, who is making sure we get the record straight. In the Qur’an, God himself speaks in the first person, directly to the Prophet Mohammed, or via his angel Jibril (Gabriel). In the passages Miles chooses, we see God issuing corrections and revisions to the narrative. Whereas the Bible uses literary devices of suspense, in the Qur’an God assumes we know the stories already: rather than retelling them in full, God edits and intervenes, distilling the lessons to be drawn.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

* According to one tally, Judeo-Christian figures appear in 1,453 verses of the Qur’an, or about a quarter of the text.-------------------------------------------------------------When God created man in his own image, it was, Miles wrote in his first book, “an unmistakable invitation to make some sense of God in human terms.” Here, it seems, the invitation has been revoked. There is no Imago Dei in the Qur’an: humankind is less grandiose than that, created “from dust, then from a sperm, then from a blood clot, then from a morsel.” God the editor is telling us, according to Miles, you’re not me. Whereas Yahweh experienced events unfolding in human time—he acts and reacts, regrets, learns—Allah removes himself from dank temporality, and speaks of the now, the past, and the hereafter all at once. The Qur’an is not ordered in a narrative sequence, but rather in an almost mathematical way, by the length of its chapters (from longest to shortest), confounding any attempt to glean character development across time. It soon becomes apparent that God in the Islamic scriptures essentially rejects the project of theography, insisting on his unknowability at every turn. Yet Miles never quite speaks to this, and the theographer persists in his quest to meet a personified Allah on the page.

In the Qur’an’s counternarratives, Noah has a disbelieving son who refuses to board the Ark, and Pharaoh dies a Muslim. And the idol of the golden calf, made of melted jewelry? It could actually bleat, God informs us. In the Tanakh, when Cain, jealous that God seemed to prefer his brother’s sacrifice, killed Abel, Yahweh was stunned to see his first human corpse. “What have you done?” he cried out to Cain, and neither seemed to know what to do next. Yet in the fifth sura of the Qur’an, Allah is hardly surprised: “God sent a raven clawing out the earth to show him how he might bury the corpse of his brother.” The famed story here becomes a lesson on proper funeral practices. Yahweh may have cursed Cain, but Allah emerges as less vengeful and more compassionate. Whereas Yahweh seemed to Miles “a work of self-creation still in progress,” Allah is understood as wizened and decisive, “more certain in advance of the universal and permanent significance of all that He says and does.” Miles writes that God as Allah is “no longer reckless, unpredictable, barely moral, highly emotional,” showing his non-Muslim readers that, in many ways, the Islamic God that emerges will be more recognizable to them than Yahweh.

One of God’s most significant edits in the Qur’an comes in the story of Jesus. God never failed his creation; there was no crisis, no need for the drama of the cross, nor any sacrificial god-lamb. God does not share his divinity with anyone; Jesus was only a mortal prophet in the lineage extending from Adam, Abraham, and Moses, to Mohammed, the final messenger. God makes a major revision in that Jesus did not actually die on the cross. Placing the blame not on the Romans but on Jews who had broken the covenant, God reveals that he foiled their plot: “They killed him not, nor did they crucify him, but so it was made to appear to them.” It may be that Jesus was carried down before he died, or that another man was there in his place, as Muslim commentators have speculated, but whatever happened, Miles writes, it “radically undercuts the Christian celebration of Jesus as the sacrificial ‘Lamb of God,’ dying that others may have eternal life.” Still, the Qur’anic narrative possesses an enchantment of its own. When the Virgin Mary goes into labor beneath a palm tree, alone with no one to help her, in her agony Jesus speaks to her from inside the womb: “Shake towards you the trunk of the palm and it will drop down on you dates soft and ripe.”

In Miles’s first two books, the point of doing a character study of God was ultimately the sense of epiphany that comes with seeing the scriptures, grindingly familiar to us for centuries, in an entirely new light. But in his latest, Miles has a new objective. Even before we have heard the voice of Allah, or of any Muslim authors, we hear Newt Gingrich, inveighing against jihadi terrorism: from an ax-wielding Afghan refugee in Germany, to the bodies run over by Islamic State–driven trucks, to the forty-nine dead at an Orlando nightclub. “I undertook this book in early 2017 in the aftermath of an American presidential election heavily impacted by continuing ‘jihadi’ attacks all over the world,” Miles writes, swerving from the timelessness of his earlier works. He opens with the theme of religious violence

only because—for you, my readers, and for me as well—terrorism by Muslims invoking the Qur’an and crying Allahu akbar has moved that unwelcome subject to the front of our minds.

Miles begins by highlighting acts of God’s violence in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, in order to show that “it would be a mistake . . . to regard any and every Muslim as a terrorist-in-waiting simply because he or she honors the Qur’an as sacred scripture.” Adopting an us-versus-them tone, he creates the effect of a book written in wartime, calling for peace.

In an odd, orientalizing thought experiment, Miles exhorts his non-Muslim readers to picture themselves Muslim:

Step into the mosque of your imagination, and as you bow down and touch your forehead to the floor saying, “God is greater,” or as you hear others saying those words in Arabic, you remember . . .

that when God placed Adam and Eve in the Garden of Paradise, He warned them that Satan would tempt them. (In the Bible, no such warning is given.)

that when they succumbed to temptation but then quickly repented, He forgave them and explained that after a lifetime on Earth . . . they could return to Paradise. (No such forgiveness or distant hope is proffered in the Bible.)

Miles continues in this mode for several bullet points, cataloguing the ways God appears more merciful and compassionate in the Qur’an. “Far be it from me to bash the Bible. The Bible is my scripture. The Qur’an is theirs,” he writes.

In writing this little italicized meditation, I hope only that by exercising your imagination just this much, you may find it a little easier to trust the Muslim next door, thinking of him as someone whose religion, after all, may not be so wildly unreasonable that someone holding to it could not be a trusted friend.

If Miles’s goal is to show non-Muslim readers how much common ground there is between the three Abrahamic faiths, it is a perplexing decision to insist on comparing “Yahweh” and “Allah.” Leaving the names untranslated transforms the one Almighty into two exotic literary characters. (In Christ, Miles never refers to the Christian God as “Kyrios” or “Theos” from the Greek.) Miles maintains that he likes this effect of making the familiar “strange.” Yet given his deeper mission, it seems imperative that in the very language he uses Miles should continue to demonstrate that his protagonist is the one and the same God. Instead, Miles treats a foreign “Allah” the way a well-meaning American might treat the Muslim next door.

It is an attempt to humanize what some might see as the enemy, yet by doing so it hardens the stereotypes on which demonization thrives. Part of the problem here is the absence of Muslim voices. Within the bounds of Miles’s project, he need not summon outside references, historical or literary, to read the divine character of Allah off the page. Beyond a scattered handful of translators and commentators, the only Muslim author mentioned is the inescapable Rumi. Yet the absence of Muslim literary voices becomes glaring when Miles finds room to bring in Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Seamus Heaney, Rudyard Kipling, Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson, Leonard Cohen, and even the 1997 film Titanic. Miles draws frequently on John Milton to shed light on Satan in the Qur’an, without mentioning any of the venerable Muslim critics, such as Abbas Mahmud al-Aqqad, who have studied Milton for the same purpose. In Miles’s afterword, when he mires himself in the thorny, unanswerable question of whether the Qur’an is actually the revealed word of God, to explore why we follow some new messiahs and prophets but not others, he discusses sci-fi cults and imagines a religion forming around Philip K. Dick called Dickianity.

The larger issue is a flawed assumption that seeps into the book and paralyzes it: that the Qur’an cannot be read as literature. “Muslims do not regard the Qur’an as literature,” Miles wrote in his book on the Hebrew Bible. “It occupies, for them, a metaphysical niche all its own.” Though he seeks acquaintance with his divine protagonist, Miles is held back by a fear of anthropomorphizing the Muslim God. He doesn’t dare play therapist. Afraid of the violence he seems so preoccupied by, Miles becomes modest because he is tiptoeing around Muslim rage: “I invite you to join me in nothing more threatening than a comparative reading,” he writes. His approach becomes apotropaic: guarding against and appeasing wrath, both human and divine. The conclusions he draws are inoffensive: for example, Yahweh seems more interested in human fertility, and Allah seems to care more that we worship him and him alone. And yet, politics intrudes on God in the Qur’an in uncomfortable ways. In answering the question of what Allah thinks of human nakedness, Miles feels compelled to refer to Abu Ghraib.

Was 9/11 another crisis in the life of God? In the weeks following the attacks, sales of the Qur’an skyrocketed. The book that first descended to earth on what is called Laylat al-Qadr, or the Night of Power, was now on the American bestseller lists. “Nothing but a sense of duty could carry any European through the Koran,” the philosopher Thomas Carlyle remarked in 1841. Whereas Carlyle found it “a wearisome confused jumble,” Miles frames it more delicately as having “little initial literary appeal.” But with the war on terror under way, Americans were reading the Qur’an as a patriotic duty, and doing so in two ways. Much like their medieval counterparts, who saw the Qur’an as the ravings of a man demonically possessed, the American war hawks mined it for evidence that Islam is a “very evil” religion, in the words of the evangelical preacher Franklin Graham. The peaceniks read it for proof that Muslims are just like “us,” and issued calls for interfaith dialogue. In the grip of a perceived clash of monotheisms, the idea was commonly invoked that, if only we could read each other’s scriptures and see how they connect, we might begin to solve religious hatred and intolerance.

Miles, now identifying as “a practicing Episcopalian,” is propelled by a similar peacenik sense of duty. (He has also become the general editor of the Norton Anthology of World Religions, a six-volume, 4,448-page compendium of religious texts first published in 2014 that promotes an ethic of scriptural literacy.) In the spirit of pluralism, Miles reminds us that, ultimately, we have no idea which of the Abrahamic testaments is truly the word of God: it is, he says, something that will only be revealed at the End of Days. Miles writes:

While we wait patiently for Elijah or Allah or Jesus or whoever to arrive and adjudicate all such disputes, we don’t want to be perpetually on guard that the guy next door may kill us if we don’t kill him first. So, let’s instead get to know him well enough to live with him in peace; and if that means getting to know his scriptures and his God, let’s take the time to do that too.

Rather than entering mosques of the imagination, or conjuring abstract neighbors, Miles might have welcomed centuries’ worth of eminent Muslim intellectuals, theologians, poets, and critics, and ventured with them beyond the limited parts of the Qur’an that overlap with the Tanakh and the New Testament. This would have deepened Miles’s portrait, freed the theographer from our hysteric news cycle, and even shown how God himself appears to weigh in on the question of whether we can read his word as a literary text. In 1947, decades before Alter and Kermode’s Literary Guide to the Bible came on the scene, a debate raged at Cairo University over a PhD thesis that approached the Qur’an as literature. Accused of “crimes against the Qur’an” in a controversy that played out in the pages of Egyptian newspapers and in heated letters to King Farouk, the student, Muhammad Ahmad Khalafallah, and his supervisor, Amin al-Khuli, argued that the Qur’an itself invites us to approach it in a literary mode. At several moments, God throws down a literary gauntlet: we should just try to author something like his verses.

If you are in doubt about what We have sent down unto Our servant, then produce a surah like it, and call your witnesses apart from God if you are truthful. (2:23)

Say, “If mankind and the jinn banded together to produce the like of this Qur’an, they could not produce the like of it, even if they were assistants to each other. (17:88)

In defense of his student, al-Khuli argued that literary criticism is the only means we have to try to comprehend this i’jaz, the “inimitability” of the Qur’an. Famously theorized in the eleventh century by al-Baqillani and the Persian grammarian al-Jurjani, the doctrine of inimitability tried to capture what makes the Qur’an so different from all other texts. What was that spellbinding effect the rhythm of the Arabic seemed to have on its listeners, even unbelievers? It was deeply poetic yet bore no relation to previously known meters, as if floating in from another world. Al-Baqillani argued that the Qur’an, neither poetry nor prose, was an entirely new literary genre, an idea prominently taken up in the mid-1920s by the towering Egyptian critic Taha Hussein. Because the Qur’an was so recognizably its own genre, the many false prophets and pretenders that emerged as competitors to Mohammed did so by imitating its unique literary form, rather than its narratives or the information it contained. The ninth-century poet Ibrahim al-Nazzam saw it as one of God’s miracles that, by imposing a sort of divine writer’s block, he had made it impossible for humans to ever author anything like the Qur’an.

It was the eloquence of the Qur’an, and the recognition of its supremacy compared with all other texts, al-Khuli argued, that first led Arabia to accept the message of Islam. “The literary method should, therefore, supersede any other religio-theological, philosophical, ethical, mystical or judicial approach,” wrote the Egyptian theologian and dissident Nasr Abu Zayd in a 2003 essay on the Cairo University debates. The author of numerous works on Qur’anic interpretation, Abu Zayd found himself persecuted by the Mubarak-era judiciary; in a sensational 1995 trial, he was declared an apostate and forced into exile. Yet until his death in 2010, Abu Zayd continued to argue compellingly that literary criticism does not denigrate the divinity of the Qur’an. After all, he wrote, the word of God descended into human language and “respected the rules” of our grammar and syntax. We must strive to understand it with the tools at hand. In the late 1980s, the Pakistani scholar Muntasir Mir showed how God in the Qur’an flexes a panoply of literary devices, from anastrophe, anaphora, and epenthesis to zeugma.

Whether or not one considers the Qur’an or the Bible to be divine, the act of interpretation, as Abu Zayd argued, is always human. (Except that one time when, along the road, the risen Christ parsed the scriptures.) It is our loss that Miles felt he couldn’t treat the Qur’an more trenchantly as a work of art, as Muslims have done for centuries. What Miles inaugurated, the method of theography, remains a brilliant way to try to meet an inimitable protagonist, even if it is, like all the best literary endeavors, an attempt at the impossible. Literary criticism remains an essential way to interpret sacred texts, in their complexity and idiosyncrasy, without having to make any claims about what their believers believe—an approach ever more urgent in the age of the Muslim ban. We might have supposed God’s biography unfolded in the clouds, distant from us. Yet with the conclusion of his trilogy, Miles has shown us, perhaps inadvertently, how—ever since God switched on the lights and created his combative human interlocutors—human politics, from the archaic to the present, fills many chapters of the divine memoir.

'宗敎' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 크리스마스는 예수 탄생일 아니라 예수 탄생기념일 (0) | 2018.12.23 |

|---|---|

| The Church That Has to Come (0) | 2018.11.02 |

| The Catholic Church’s Biggest Crisis Since the Reformation (0) | 2018.10.15 |

| 종교가 없어도 善한 삶 살 수 있다 (0) | 2018.09.15 |

| The Buddhist monk who became an apostle for sexual freedom (0) | 2018.09.04 |