There are horror stories about what can go wrong on release day, and then there is the story of John Fante. There has always been a rich genre of heartbreaking tales of what could have been — from albums released on September 11th to sculptures destroyed in transit — and then there is the novel Ask the Dust, a book whose tragic bad luck is spoken of in hushed tones — passed from writer to writer and repeated endlessly by critics and journalists — as the ultimate publishing nightmare.

The fact that a brilliant work would not be appreciated in its time is not, in and of itself, a remarkable event. But the nearly unbelievable (and up until now, largely unconfirmed) how of Ask the Dust, now widely considered to be a sort of West Coast Gatsby — which was released to rave reviews in 1939 but did not begin to find its audience until the early 1980s as Fante, then a double amputee, lay dying of diabetes — was not some inexplicable, unavoidable force majeure. It was not ill-health or racism or hubris. It was something much more specific. It was something with a face and a name. Really just one name, in fact.

Hitler.

While the list of artists victimized by the Nazis is long — from Stefan Zweig to Felix Nussbaum — few of them were first-generation Italian immigrants living and writing books in sunny Southern California. Very few of those tragedies were rendered through a decision by a U.S. Federal Court. And of course, none of them were ultimately redeemed by a chance encounter on the shelves of the Los Angeles Public Library nearly a half-century later.

What follows, then, is one of strangest sagas in all of publishing — perhaps in all of art. It is a story of greed and stupidity, of bad timing and eventual vindication. Ultimately, it’s the story of how some of the “finest fiction ever written in America” managed to triumph over undeniable evil. And it’s one that deserves the consideration of every creator, every publisher, every copyright attorney, and, as it looms ever larger, of anyone involved in the debate of what it means to #NoPlatform offensive and hateful speech.

The Truth Is Always Stranger Than Fiction

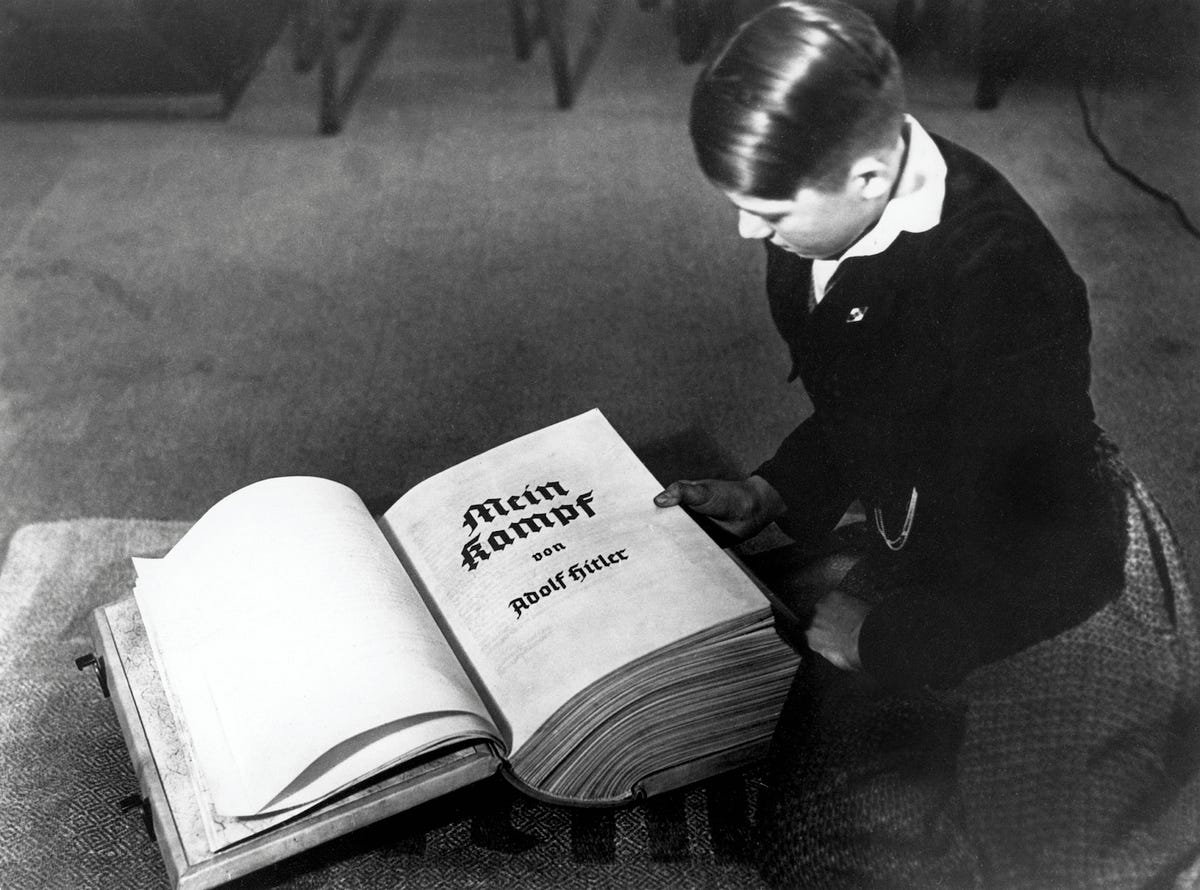

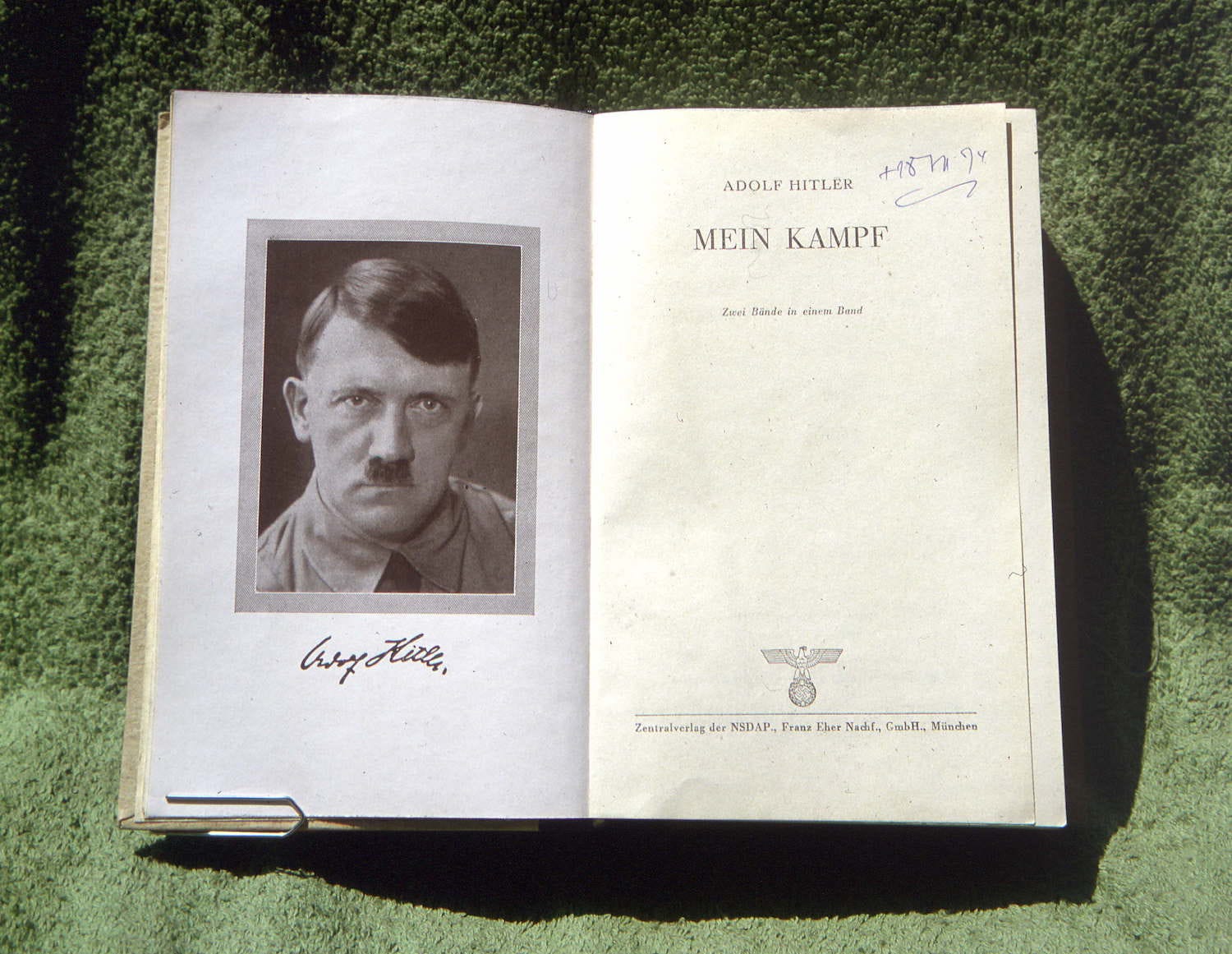

It does not seem that Houghton Mifflin — which had been a publishing powerhouse since the late 1800s — ever considered not publishing the dictated prison memoirs of the rising Austrian politician. Adolf Hitler had published Mein Kampf — a shortened version of its original title, Viereinhalb Jahre (des Kampfes) gegen Lüge, Dummheit und Feigheit (or, “A Four and one-Half Year Struggle Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice”) — in 1925, in part to pay off his legal fees and fund his political ambitions. It was a steady seller in Germany as his political fortunes rose, increasingly becoming a book of international interest.

A young German boy reading ‘Mein Kampf’ in 1938. Photo: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

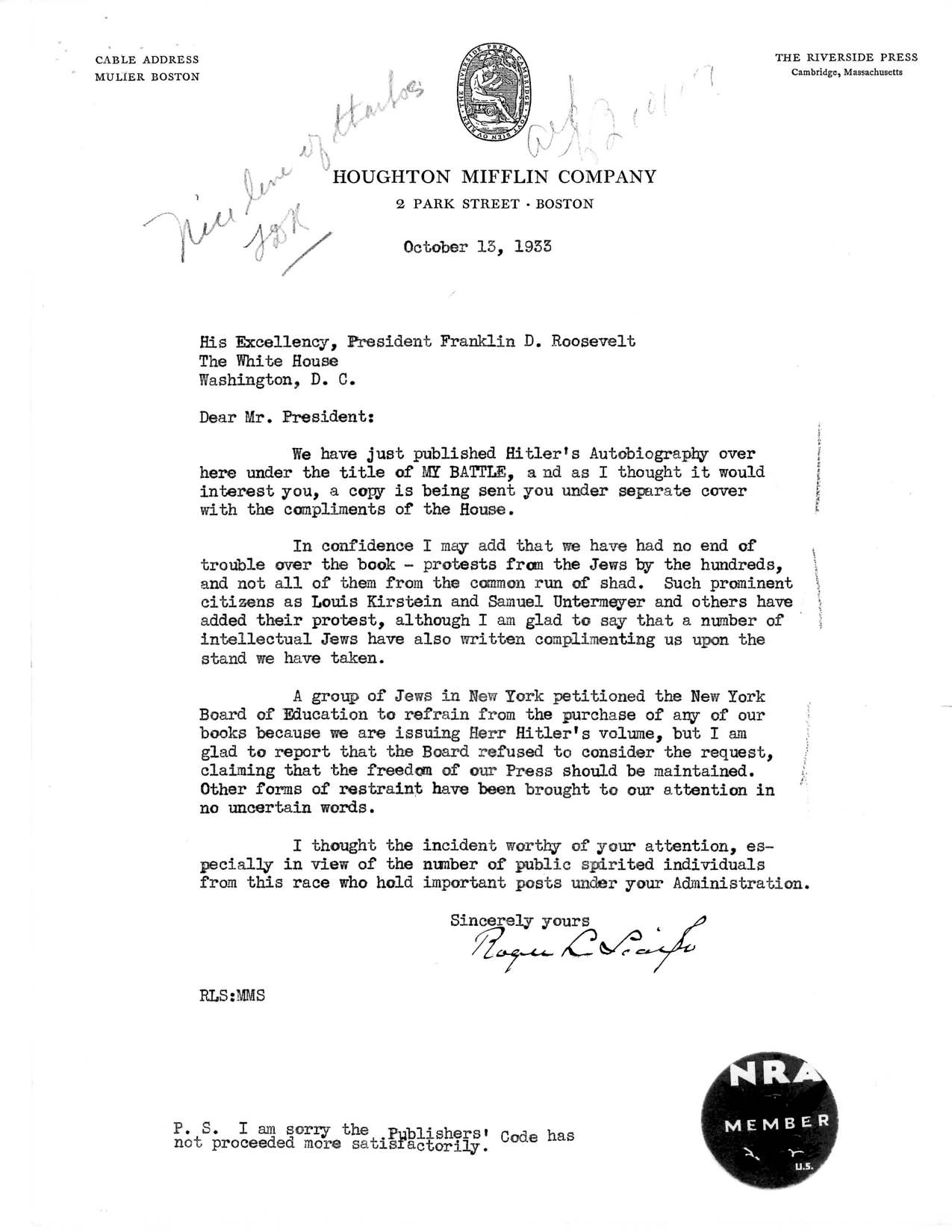

After seeking approval from its board, Houghton Mifflin’s editors set out to acquire Mein Kampf just two months after the Reichstag fire gave Hitler the pretext for dictatorial powers in Germany. The company, with its history of snagging lucrative exclusives on overseas political books, was the perfect partner for Eher-Verlag, the publishing house controlled by Hitler in Germany. The two houses, one in Boston, one in Munich, quickly reached an agreement for an exclusive license which, at the then-standard royalty rate of 15 percent, would have paid Hitler roughly 50 cents per copy. The publication announcement for My Battle, (as Houghton Mifflin titled their first edition of Mein Kampf) on July 13, 1933 exhibits Houghton Mifflin director Roger Scaife’s flair for publicity and hyperbole:

For the first time the German Dictator speaks to the American people. In the form of an autobiography, he tells the stirring story of the growth of an idea from the beginnings to the proportions of a great national movement and his own meteoric rise…

To publish an author who had already begun to push the world to the brink of war was controversial, even in the mid-1930s. So too was Houghton Mifflin’s decision to publish a version of Mein Kampf which omitted some of Hitler’s darkest rants about Jews, edits made by Nazi agents who hoped the abridged edition would make his views more palatable overseas.

What explains this? It’s only slightly uncharitable to suggest there may have been ideological sympathies between Hitler and the leadership at Houghton Mifflin at the time. The advance copy Roger Scaife sent to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt included a note, apprising him of recent objections from New York City schools of Houghton Mifflin-published textbooks:

In confidence I may add that we have had no end of trouble over the book — protests from the Jews by the hundreds, and not all of them from the common run of shad…. although I am glad to say that a number of intellectual Jews have also written complimenting us upon the stand we have taken.

This was important for FDR to know, Scaife concluded, due to the “number of… individuals from this race who hold important posts under your Administration.” In a note that accompanied a complimentary copy of the book, Roger explained to Hitler in October 1933 that, despite strong opposition, Houghton Mifflin had “nevertheless, persisted in our plans, and we believe that the actual publication of the book will result in wide discussion and, we hope, in satisfactory sale.” FDR, who had also read the book in its original German, took the time to write inside his pre-publication copy of My Battle, “this translation is so expurgated as to give a wholly false view of what Hitler is or says.”

The truth was, most Americans had interests outside of German politics in 1933 — namely the Great Depression, which was then in its fifth year. There would eventually be enough Nazis in New York City to fill Madison Square Garden — which they did, for the now infamous German American Bund Rally in 1939. But in 1933, Mein Kampf had sold just 4,633 copies in the U.S. (compared to worldwide sales of roughly 1 million copies, mostly in Germany, since publication). By 1937, sales had slowed to 1,723 copies in the U.S. (Meanwhile, newlyweds and soldiers in Germany were given free copies at the expense of the state. The German government also forgave Hitler’s tax debt on the copies he’d sold before taking office.)

In the fall of 1938, as appeasement reigned in Europe and the Munich Agreement gave Hitler the concessions needed to annex Czechoslovakia, American interest in his book began to spike. Between September and October of 1938, Mein Kampf sold more copies alone than it had in all of 1934. In the end, American sales in 1938 eclipsed all the previous years combined. Hitler had already sold millions of copies in Germany, but now he was a bestseller in the free world.

It wasn’t simply his overseas exploits driving sales. Houghton Mifflin moved aggressively to market the book, improving accessibility and price with a more mass-market edition. The new edition included a blurb from Dorothy Thompson, an American journalist who had been expelled from Nazi Germany. “As a liberal and democrat I deprecate every idea in this book,” she wrote. “The reading of this book is a duty for all who would understand the fantastic era in which we live, and particularly it is the duty of all who cherish freedom, democracy and the liberal spirit. Let us know what it is that challenges our civilization.”

Initially, Hitler’s representatives were not pleased with the branding changes, and demanded an explanation and improvements. The managing editor for Houghton Mifflin attempted to placate their German business partners in a letter, explaining the publisher’s logic. “The sales of the book in the original printing had not been up to our expectations, and we believed that a new promotion effort, of which this jacket is an important part, was desirable in order to secure for the book the distribution that its importance unquestionably deserved,” Ira Rich Kent wrote to Arthur Teele, the lawyer for the German consulate in Boston, in March of 1937. He turned out to be right, and the increased sales — some 14,000 in 1938 — flattered Hitler’s vanity enough to satisfy him.

Perhaps by then, the book had already served his plans for world domination and was no longer a priority. Perhaps he was too busy and rich to care, having earned millions from sales at home and across Europe. In the years since Houghton Mifflin first published Hitler in the U.S. in 1933, he had gone from the legitimately elected German chancellor to, after the Reichstag fire, dictator. A year later, the Night of the Long Knives purged the country of most of his political enemies. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws excluded Jews from citizenship. By 1937 and 1938, Hitler’s designs on Austria were in the air.

This was no longer simply a book by a charismatic international politician. Likely in response to the rising criticism of their association with Hitler, and the poor optics of their highly sanitized first edition, Houghton Mifflin began negotiations with translators for the full manuscript of Mein Kampf, which would, for the first time, leave nothing out.

Wrong Place, Wrong Time

In 1938, John Fante, an ambitious 29-year-old son of an Italian immigrant — whose writing had kept him only a meal or two from starvation up until that point — published his first book, Wait Until Spring, Bandini, with publishers Stackpole and Sons.

It is a beautiful novel that first introduced what would become a recurring character in most of Fante’s books: Arturo Bandini. Bandini, largely based on Fante himself, had endured intense anti-Italian bigotry from his fellow Americans; he was egotistical and delusional and hilarious; and like his creator, he was an aspiring novelist. Fante’s novels mix desperation and hubris, hope and pain; they are somehow uniquely American in their optimism. The same year Bandini was published, Fante began to float the idea of a second book to his editor at Stackpole, William Soskin. The book would become Ask the Dust, an ode to love and Los Angeles.

As 1938 came to a close, Soskin wrote to let Fante know that he and General Stackpole, a World War I hero and the owner of the publishing house, very much wanted to publish the book. “With the obstacles and difficulties of a first novel fairly successfully over,” he wrote, “and with a considerable reputation established,” expectations for the book were high. “The market will be receptive,” he wrote, “and they will believe everything we tell them. So it looks like fairly clear sailing.” To Fante, who had lived in crippling poverty all his life, it was the closing words that would have landed most encouragingly: “The very best Christmas wishes to you, and may you be filthy rich next year.”

It appears that Soskin, like all editors, was at least partly telling his author what he wanted to hear. Though Wait Until Spring, Bandini had been well-received by critics, it was not a smashing success. The idea that the market was clamoring for a second Fante novel was probably wishful thinking, and the advance Soskin offered for Ask the Dust reflected this, at some $800 (about $14,300 in today’s dollars). It was, in the house’s estimation, enough to cover Fante for the four months it should take to write the book.

It didn’t take much for Soskin to convince Fante that he was destined for greatness. Bandini, his alter ego, already knew it. This was a character who already saw himself on the shelves next to Dreiser and Mencken and would go to the library to fantasize about his place in the literary pantheon. “Hya Dreiser, Hya Mencken,” he writes in Ask the Dust, “Hya, hya: there’s a place for me, too, and it begins with B, in the B shelf, Arturo Bandini, make way for Arturo Bandini…old Arturo Bandini, one of the boys.”

It happens that as Soskin was writing to Fante, he was simultaneously in hot pursuit of another egotistical and often delusional author — the very same one Houghton Mifflin had been publishing since 1933. Because Adolf Hitler renounced his Austrian citizenship in 1925, he listed himself as a “stateless German” when copyrighting Mein Kampf that same year. This technicality was one of Stackpole and Sons’ possible justifications for publishing an author already with another publishing house; under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1909, the book was in the public domain. Better, an edition of Mein Kampf that did not enrich its despicable author would provide an attractive alternative at a time when Americans were attempting to understand the growing threat in Europe. Publishing it was basically a public service… and free money.

Approaching — perhaps attempting to poach — the very translators Houghton Mifflin was negotiating with for their new unabridged edition of My Struggle, Soskin and Stackpole revealed their plans to enter the market that Houghton Mifflin believed they legally controlled. In his fascinating and definitive paper on the publishing of Mein Kampf in the United States, Professor Donald Lankiewicz of Emerson College writes of Houghton Mifflin’s quick moves to block intruders from interfering with their exclusive hold on the book. Hitler’s agents were notified in Berlin and help was requested to curtail Stackpole’s effort. Lankiewicz speaks of a heavy-handed call from Henry Laughlin, president of Houghton Mifflin, to General Stackpole to dissuade him from publishing his edition of Mein Kampf. It would be highly “unethical” to interfere with Houghton Mifflin’s copyright, he said, and serious losses were possible if Houghton Mifflin and Hitler’s claims were upheld in court.

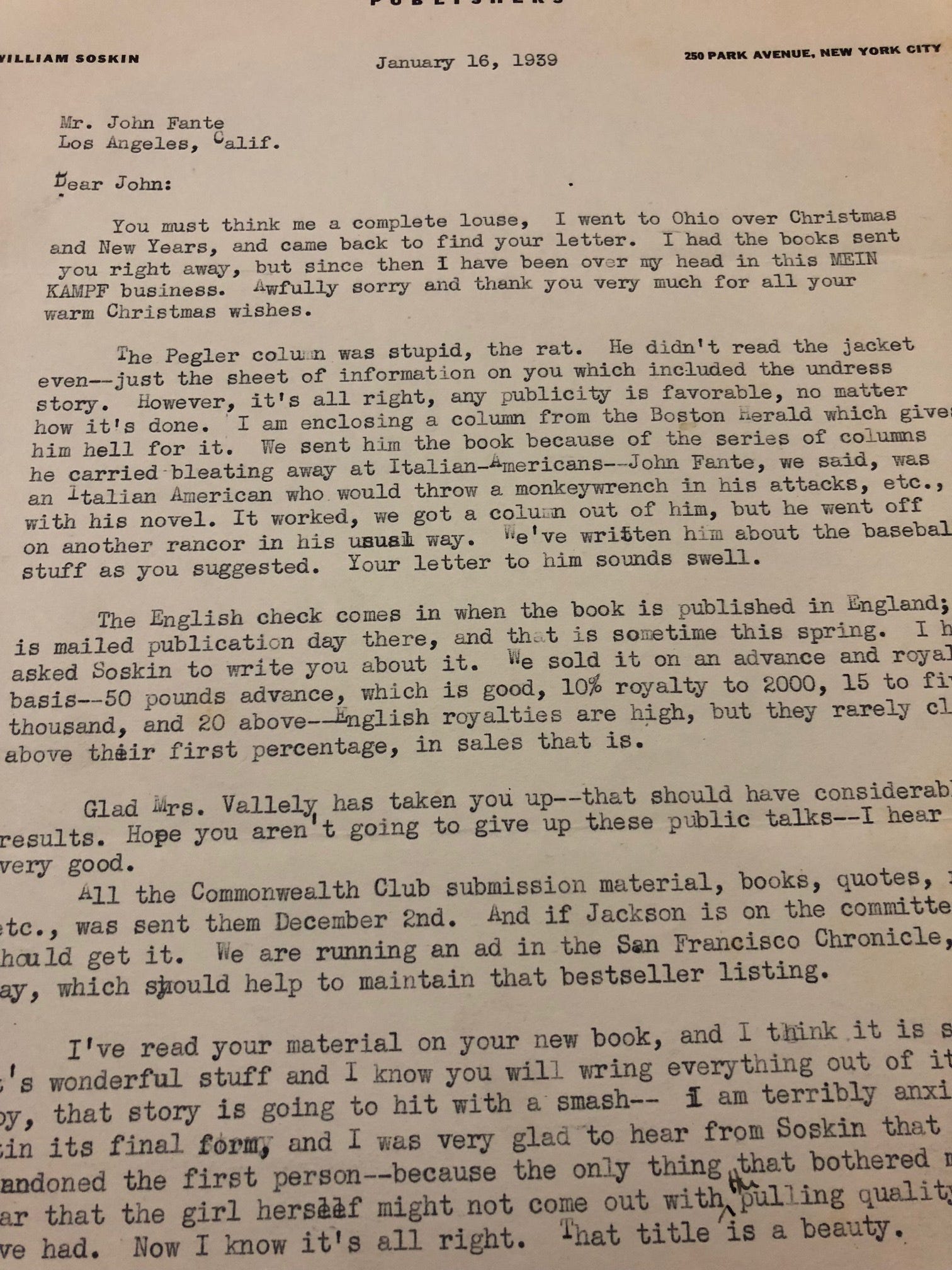

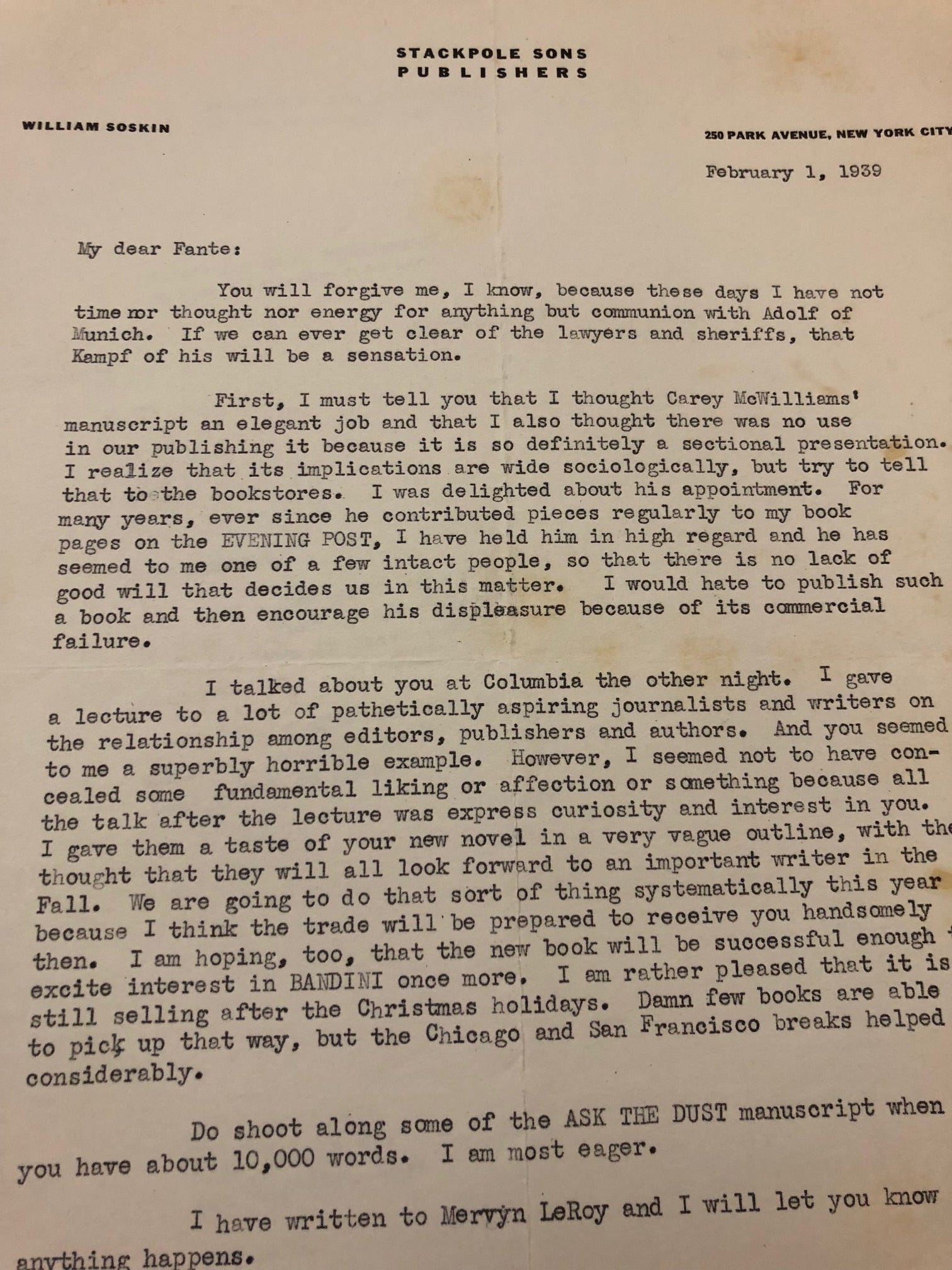

Showing far more spine than most of Europe had toward Germany’s gangster tactics, General Stackpole proceeded anyway. But the effect was almost immediately felt on the publisher’s other titles. “You must think me a complete louse,” the editor William Soskin wrote to Fante in January 1939, explaining that the “MEIN KAMPF business” had delayed his response to a marketing inquiring. “You will forgive me,” he wrote again a few weeks later. “I know, because these days I have not time nor thought nor energy but communion with Adolf of Munich.”

Early 1939 found both houses, Houghton Mifflin and Stackpole, racing to get their competing unabridged editions to market and, on February 28, 1939, both did so. According to Cabinet Magazine, Houghton Mifflin’s edition sold 30,000 copies in the first month. Stackpole’s edition billed itself as unauthorized with the prominent tagline “This Edition Pays No Royalty to Adolf Hitler.” (This practice led to a severe rebuke from the New Yorker, which took issue with Stackpole “getting out of paying royalties to any author, even on the noblest grounds.”)

It too sold well. Houghton Mifflin, in partial response to the marketing of its new competition, promised to donate “profits” from the unabridged version to refugee charities — charities aiding those who’d been displaced by the author, who would continue to collect royalties.

Houghton Mifflin’s threats against Stackpole had not been idle; their obligations to Hitler all but required them to pursue legal action to defend their copyright. In January 1939, just before the unabridged versions were released, Houghton Mifflin, splitting the legal costs with Hitler’s publishing house, sued Stackpole and Sons in a U.S. Federal Court. It’s a remarkable occurrence that rewrites the early history of World War II: Hitler’s first real battle against an American veteran actually began a full two years before the U.S. declared war on Germany, and he was aided by the publishing house who brought us Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau (as well as providing, to this day, textbooks to millions of school children).

Despite the brisk sales of both editions — 11,500 copies for Stackpole in just a few months — the legal costs of this battle were significant. We can imagine the drain on an independent publisher like Stackpole and Sons was far greater than it was on Houghton Mifflin. It was not a simple case, ultimately involving several appeals and higher courts. Houghton Mifflin’s earliest attempt for an injunction against Stackpole’s edition in February 1939 had been denied, with the judge finding that Stackpole “raised questions of title and validity as to plaintiff’s copyrights which were not free from doubt, and that the issues could not properly be determined on affidavits.” But surviving summary judgment was hardly a victory for Stackpole, since it only delayed the inevitable.

In June 1939, Stackpole’s number came up. Judge Charles Clark handed down the first of the rulings in Hitler’s favor, dismissing Stackpole’s novel claim to Mein Kampf by asserting that a stateless person is in fact “entitled to the benefits of the American copyright laws.” Nor was the court swayed by the public’s right to read and understand Hitler’s works without actively supporting his ambitions with their wallets. “Under the circumstances of entire absence of title or right in the defendants,” Clark wrote in his decision, “their claim that the equities are in their favor — that they are engaged in a service of great social value in thus publishing this book — seems indeed bold.”

Twelve weeks before Hitler’s tanks rolled into Poland, his propaganda was winning its first legal victories under U.S. Federal Law, aided by a publisher, Houghton Mifflin, who profited from every newspaper headline and radio denunciation of the German dictator. In late October 1939, as the Nazis began deporting Jews from newly captured territories, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Stackpole’s petition to hear the case.

In 1940, as British forces fought their way out of disaster at Dunkirk and France surrendered completely to the Nazis, Stackpole and Sons continued to fight a desperate legal battle to prove that Houghton Mifflin’s contract with Hitler might somehow be invalid and thus undermine their ability to enforce it. Like the armies of Poland and the Netherlands and France and Denmark and Norway, this effort was doomed to failure. In 1941, as Operation Barbarossa — Germany’s reckless invasion of Russia — commenced, Hitler took a moment to confirm, through his publishing operation, that he had, in fact, authorized Houghton Mifflin as his agents, validating the contract. on August 7, 1941, the court made its final ruling against Stackpole. In September, it announced damages.

Enjoined from selling their copies, Stackpole was not only out their legal fees — Houghton Mifflin’s fees were $23,000, and we can assume Stackpole’s were similar — they were also out the cost of translating and printing the thousands of copies they had produced. The judgment later required the house to pay Houghton Mifflin — and indirectly, Hitler — some $15,250 in proceeds from the copies they had sold.

Victory was complete. The bad guys had won.

Why Did ‘Ask The Dust’ Fail?

The legend of John Fante has held that the legal battle with Hitler over Mein Kampf bankrupted his publisher and prevented the world from recognizing Fante’s brilliance in his own time. Neil Gordon, writing for the Boston Review in 2017, repeated a version of this, saying, “Stackpole and Sons was even sued out of existence by Adolf Hitler, for unauthorized publication of Mein Kampf!”

Like all legends, much of it is contradicted by basic fact.

Stackpole and Sons is still in business today as Stackpole Books, and has published hundreds, if not thousands, of books since 1939. It also misses what’s so truly incredible about what happened: Stackpole and Sons wasn’t killed by Hitler. They were kneecapped by an American publisher on his behalf.

But is this what prevented Fante’s classic novel, heralded by William Saroyan at release as an heir to the tradition of Tom Sawyer, from reaching the audience it deserved?

It’s less clear than one might suspect.

Stackpole’s small print runs of Fante’s books, particularly Bandini which was released prior to the publisher’s pursuit of Mein Kampf, indicates they had relatively low ambitions for the author in the first place. The print run for Ask the Dust was only 2,200 copies and was priced 50 cents lower than his previous book.

Judith Schnell, the current editor and publisher of Stackpole Books, explains that this was quite typical for their house at the time: “Stackpole’s model was to publish books and put them out there. I don’t think there were any huge PR campaigns or publicity campaigns. It wasn’t that kind of company and it still isn’t that kind of company.” The argument being that Fante’s marketing budget couldn’t have been seriously affected if he didn’t have one in the first place.

Nor could he have been deprived of a mass audience if the material was too far ahead of its time or unsuitable to a mass audience. John Martin, publisher of Black Sparrow Press — the house who would rerelease Fante’s books in the early 1980s — would argue that while the lawsuit certainly didn’t improve Fante’s chances of success, the results were likely to have been the same without it. “You’ve got to remember that Bandini and Ask The Dust were published in the depths of the Great Depression. And both are serious literary works rather than novels written for wide circulation.”

In other words, it’s just as likely that the American public didn’t have the appetite for Fante’s prose. Fante himself was in no position to support the books (or follow-up immediately with other novels), as he spent, at least for part of the war, working for the Office of Strategic Services. Hitler was, of course, to blame for both of these circumstances, but Stackpole’s publication of Mein Kampf, less directly so. Other previously underappreciated authors, F. Scott Fitzgerald being an apt comparison to Fante, found rabid audiences in soldiers and citizens alike, during the war.

Stephen Cooper, Fante’s biographer and longtime booster of his work — and the person who encouraged me to dig deep through Fante’s archives at UCLA and to scrutinize the Hitler narrative — raises an inconvenient piece of evidence about Fante’s second book. “In contrast to the really consistently positive reviews that Bandini got, the response to Ask the Dust [at the time] was a mix of negative and positive and neutral,” Cooper said. Critics can’t blame Hitler for why they missed what later generations recognized.

Charles Bukowski, who brought Fante’s books to Black Sparrow Press and once called him his “god,” explained in an unusual written interview done in 1977 why he believed Fante had failed to reach readers:

See Mozart, Van Gogh, and so forth. It’s the angle of the action, the people aren’t ready, it’s the weather, it’s the diet, it’s the shoes they wear and most of the people are almost always out of touch with the best and the most real because they never had a chance to know what it is.

Counterintuitively, Bukowski argued that the passage of time may have actually been what allowed Fante’s groundbreaking work — which featured drugs and sex and wrestled with race — to become more palatable. “The fact that his writing is not of the exact present might remove some of the fear that people have of an outward and direct art-statement.”

Yet, each of these explanations has a way of letting everyone off the hook. No author, certainly no artist, who understands the high-wire act of releasing something great into the world, would accept the idea that the books were destined to fail. “You can’t say it would have happened anyway. You have to say we don’t know. We know for certain it deserved to succeed,” Frank Spotnitz, the producer of the hit television show The Man in the High Castle and producer of a forthcoming documentary about Fante, said.

Fante was himself asked what he thought happened, almost 40 years to the day that Stackpole and Sons would first become distracted and delayed in answering his letters. With the benefit of significant distance, but before his resurrection story would become the stuff of myth, Fante explained that right as demand for Ask the Dust was picking up, stores began to run out of copies between the first and second printings. He was speaking to a salesman at a bookstore when he finally connected the dots. Hitler. Mein Kampf. Stackpole. Copyright law.

“To me, that didn’t seem like anything because how could Hitler sue and win a case in the United States?” Fante told an interviewer in 1978:

But sue he did and win he did and so they kept pushing this cause célèbre right up through to the Supreme Court and it took over a year and all of the publisher’s money, all of the exploitation [promotion] money for their whole season that year, was absorbed by this litigation. And not a word was said about Ask the Dust. So it was just canceled out because there were other, more important books to fight for.

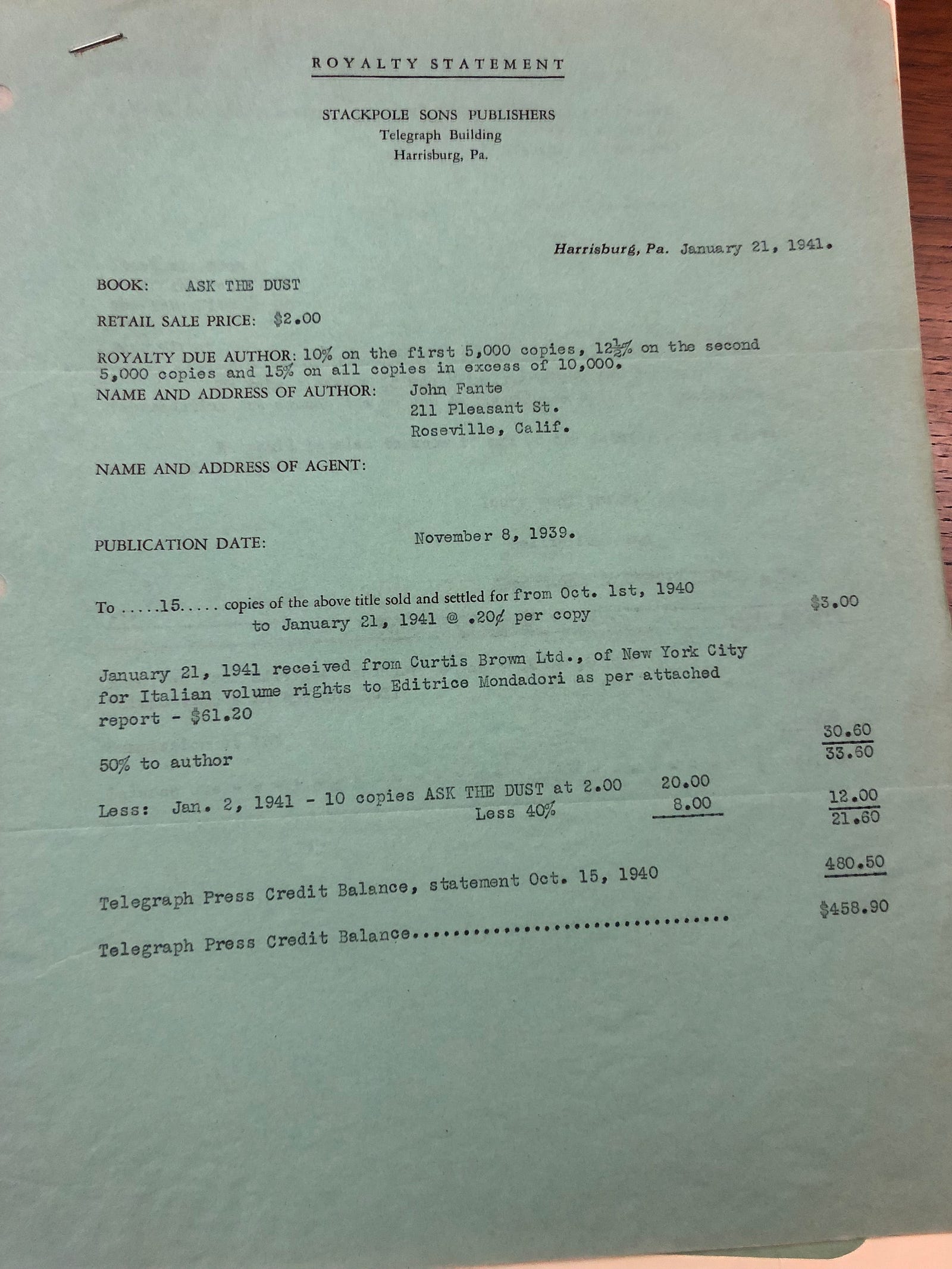

Does this hold up? Or is this the wishful thinking of an author whose book was simply ahead of its time? Thanks to Fante’s wife, Joyce, we have a definitive answer. Joyce, a meticulous organizer and supporter of her husband’s work, kept Fante’s royalty statements from Stackpole and Sons. Fante’s royalty statement from January 21, 1941 shows that as of October 15, 1940, less than a year after Ask the Dust’s release, he had earned back nearly half of his $800 advance. At the 20 cents royalty he was paid per copy, this means that in less than 12 months, his book sold roughly 1,600 copies of a 2,200 copy run.

Not only does this confirm Fante’s claim that his book was selling well at release, but the numbers contrast starkly with the next two royalty periods, which show Ask the Dust selling just 15 and 19 copies. Authors simply don’t go from selling out the majority of their first printing to selling no copies, barring some serious intervening event.

Like a lawsuit from Hitler.

The Gods Taketh, But Also Giveth

It was unquestionably a stroke of bad luck for John Fante to release his novels when he did. “It would almost be funny if it weren’t Adolf Hitler,” Spotnitz said. “And it’s so random because John Fante had absolutely nothing to do with the decision. It’s a tragic twist of fate that his publisher did this and John Fante was victim.”

However, Fante’s profound bad luck was counterbalanced by unlikely good luck. His story is not that of Sixto Rodriguez, where the unappreciated genius toils away in poverty. The post-war years were quite good to Fante. He didn’t write many more novels, but his day job as an in-demand screenwriter paid the bills. Fante’s earnings allowed him to provide for his family and a large estate in Malibu. In 1952, he wrote a novel called Full of Life — which he later would classify as a continuation of the Bandini series — about a struggling writer in Los Angeles with a pregnant wife, a drunk father, and a crumbling house he cannot afford. It was not a very good book, he later admitted, and he had written it for money. And in that, he succeeded: book sales, film rights (the movie adaptation for Full of Life starred Judy Holliday and Richard Conte), and serial rights netted him more than $150,000 at a time when the average house in Los Angeles cost $12,000. Between the 1930 and the 1970s, Fante worked for studios like Fox, RKO, MGM, and Warner Brothers, as well as on projects with directors Orson Welles and Dino De Laurentiis. He also sold many short stories to outlets like American Mercury, Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Bazaar, and Scribner’s.

According to biographer Stephen Cooper, if there were anything Fante held a grudge about, it was actually Hollywood, not publishing. “He had way more bitterness about his Hollywood career,” Cooper said. Other novelists, William Faulkner being one, had been tempted by Hollywood and grown to hate it, too — a fact that he and Fante commiserated over at the bar of Musso and Frank’s many times. Fante’s novels might not have sold well, but they were published, and the critics were usually kind to them. The vast majority of Fante’s screenwriting, as is true for many well-paid hacks, never saw the light of day. In Hollywood, Fante was never in control and despite his large salaries, he was just another writer employed by the studios. Interchangeable. Disposable.

The only difference between Fante and the rest of his now mostly forgotten peers is that the wheel was coming back around on Ask the Dust. The copy stocked by the Los Angeles Public Library in Downtown LA appears to have possessed singularly magical powers. Charles Bukowski checked it out and fell in love with it. So did Los Angeles Times contributor and poet, Ben Pleasants. The screenwriter Robert Towne found Fante while researching at the library for the movie Chinatown.

Together, these three men independently recognized the beauty of the prose and each contributed significantly to its rediscovery. Bukowski wrote about Fante in one of his books. Ben Pleasants interviewed Fante for a number of outlets and interested several publishing houses in the titles.

On February 28, 1968, Fante received a letter that released him from his contractual obligations to the publisher which had discovered him as a novelist but had also, in tangling with Hitler, set his career back as much as several decades. In 1977, he published his first novel in 25 years, The Brotherhood of the Grape. It was reviewed in the New York Times and the Washington Post. Robert Towne optioned the movie rights and Francis Ford Coppola liked it enough to publish a large excerpt in his City magazine.

Most interesting was the publisher that Fante chose for the book: Houghton Mifflin. Clearly not holding a grudge against the company that may have submarined Ask the Dust, Fante’s main complaint was that he and his editor didn’t become closer while creating the book. It wasn’t like the old days, he said, when the publisher and writer actually talked to each other. No correspondence with the General, like there had been at Stackpole. Despite the critical praise, the book was not a notable success — though by then, Fante had been let down enough that it didn’t seem to get to him.

“I think the one thing that a writer must avoid is bitterness,” John Fante told Ben Pleasants in an interview in 1979. “I think it’s the one fault that can destroy him. It can shrivel him up… I’ve fought it all my life.” His son, James Fante, looks back on his father’s complicated journey with regret and pride:

I’m not naive enough to think good work always wins out in the end. There are plenty of painters who died in Auschwitz. I don’t necessarily think there is justice in the world, it’s that he had the strength of character not to let it break him.

(If only Fante, who often saw his own life happening to him “across the page in a typewriter,” could have turned his own heartbreaking and unbelievable story into fiction!)

In 1980, Fante was again in the hands of a small independent publisher, this time it was one who would deliver on the dreams William Soskin had promised in 1938. John Martin of Black Sparrow Press had been given Fante’s novels by Bukowski and Pleasants and loved them. He republished Ask the Dust and quickly followed with Fante’s other books. In 1982, he published Fante’s last book, Dreams from Bunker Hill, which Fante, now blind and without legs, dictated to his wife, Joyce, to conclude the Arturo Bandini series.

Since their rediscovery, Fante’s books have sold hundreds of thousands of copies in the U.S. and even more internationally. In France, he has sold more than a half million copies. Ask the Dust was turned into a movie (sadly, a forgettable one) starring Colin Farrell and Salma Hayek. Italy hosts the John Fante Festival in Abruzzo each year. In 2018 alone, BookScan shows Fante moving more copies of Ask the Dust than that entire first printing. In 2019, the book will celebrate its 80th anniversary and his status as the patron saint of his city is indisputable.

If Fante’s work had not been preserved in the volcanic ash of Hitler’s explosion onto the world, if Fante had instead continued to publish novel after novel, who can say whether his books would have survived as such pristine and timeless artifacts of the city he loved.

In Ask the Dust, Fante wrote:

Los Angeles, give me some of you! Los Angeles come to me the way I came to you, my feet over your streets, you pretty town I loved you so much, you sad flower in the sand, you pretty town.

In 2010, the City of Los Angeles officially named the intersection of 5th and Grand Streets “John Fante Square.” Twenty-seven years after his death, in a Downtown LA transformed by condos and new businesses and a renaissance of young writers and artists, Fante was given the love he had cried out for so earnestly in 1939.

‘Mein Kampf,’ the Backlist Bestseller

In December 1941, when the U.S. finally declared war on Nazi Germany, the evocation of the Trading With The Enemy Act of 1917 effectively ended Houghton Mifflin’s relationship with Hitler and his agents. Prior to the declaration, Houghton Mifflin had been deducting its share of the costs of the legal battles to protect the book — including an additional case that involved future U.S. Senator Alan Cranston (California), who had published an anti-Nazi tabloid version of Mein Kampf which he claimed later sold more than half a million copies. In 1942, the year in which The New Republic published some of the first serious reporting on Nazi concentration camps, the U.S. government seized roughly $30,000 in royalties from Houghton Mifflin that would have otherwise made its way overseas to the coffers of the dictator the Allies were now attempting to destroy.

The news was not as upsetting to Houghton Mifflin as one might suspect. Not only had they already sold hundreds of thousands of copies of Mein Kampf by 1942, they were now free from the shackles of their former murderous business partner. No longer limited by any editorial constraints from Germany, Houghton Mifflin began work on a third edition to be translated by Ralph Manheim. Released in October 1943, the New York Times observed that the edition was a public service which, for the first time, rendered “Hitler’s prose almost as unreadable in English as it is in German.”

The book was again a cash cow for both Houghton Mifflin and the U.S. government during the war, and later became so for the Justice Department who, after closing the Office of Alien Property Custodian, continued to seize the author’s royalties amounting to some $139,393. The relationship between Houghton Mifflin, the U.S. government, and Mein Kampf continued until 1979 when, after some negotiation in October of that year, Houghton Mifflin purchased the rights fully from the Justice Department for less than $40,000. Between 1979 and 2000, Houghton Mifflin continued to sell Mein Kampf and retained all the net revenue, which a bombshell report from U.S. News and World Report estimated was between $300,000 and $700,000.

It was only after public fallout from these revelations that Houghton Mifflin in 2000, after many many decades of quietly profiting from what is arguably the most toxic book ever published — and aggressively defending their right to do so — announced the donation of any post-1979 profits from Mein Kampf to Holocaust-related charities.

With the rise of the alt-right and other controversial figures in the U.S., the concept of #NoPlatform has become popular with activists and critics. Inside the publishing industry, there has been debate over whether to #NoPlatform incendiary figures like Milo Yiannopoulos. Yiannopoulos’s book was ultimately cancelled by Simon & Schuster, though not before authors like Roxane Gay returned advances and moved to other publishers. (Yiannopoulos’ self-published book still reportedly sold over 100,000 copies on Amazon.) Despite this, there has not been much reflection about publishing’s past, or even current, enabling of such figures.

It’s an impossible-to-answer but urgent question for us to ponder: Could WWII have been prevented had more Americans seen the full evil of Hitler’s blueprint for destruction and domination? Churchill reflecting on Mein Kampf would call it a “new Koran of faith and war: turgid, verbose, shapeless, but pregnant with its message.” Would Stackpole and Sons’ edition have allowed Americans to see that earlier? Or was the book a dangerous work of propaganda, every cent made off of its evil words — whether they went into Hitler’s pocket or not — stained with blood?

Should Hitler have been #NoPlatformed, or could more platform, as Houghton Mifflin continues to provide for future generations, have exposed the world to his plans before it was too late? That is the question.

Nearly every publisher involved in the dispute over Mein Kampf tried, in one form or another, to argue that their interest in the book was motivated by increasing awareness, rather than profits. Even today, Houghton Mifflin’s edition — which is ranked at 11,000 on Amazon as of this writing and lists for $23.99 — has this description:

We cannot permit ourselves the luxury of forgetting the tragedy of World War II or the man who, more than any other, fostered it. Mein Kampf must be read and constantly remembered as a specimen of evil demagoguery.

It took a number of requests before Houghton Mifflin offered me a statement for this story — understandably so, given that there are few inquiries less desirable than those regarding your company’s working relationship with Nazis. Declining to answer specific questions, even those relating to John Fante’s books, they were willing to say the following:

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s decision to continue printing and disseminating Mein Kampf has not been without deep consideration. As a learning company first and foremost, HMH remains steadfast in the belief that, while difficult, the value in making Mein Kampf accessible lies in its potential for ongoing education and awareness. By studying the work as a historical artifact, our hope is that we can learn from the atrocities of the past to help create a brighter future.

All proceeds from the book are donated to Jewish Family & Children’s Services of Greater Boston for direct support of the health and human services needs of Holocaust survivors and their families.

I asked Andrew Wylie — one of the world’s most powerful literary agents with a long track record of selling and securing lucrative foreign rights deals — whether publishers today would dare publish the propagandist memoirs of strongmen like Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un or Rodrigo Duterte. He replied via email, “They probably would, I’m afraid.” When asked the same question, Stephen Cooper told me, “Of course they would, they wouldn’t hesitate.” And would they move to protect their copyright if another publisher attempted to produce their own edition? Judith Schnell, still helming the 90-year-old Stackpole Books — which continues to publish books about military history and occasionally, even books about German military history — finds little fault with Houghton Mifflin’s 1939 decision. “If that happened today and we had the license and another publisher published a version and didn’t have the license to publish…” she said, leaving the hypothetical hanging. “If you have a contract with an author, you’re obligated to uphold the terms of the contract.”

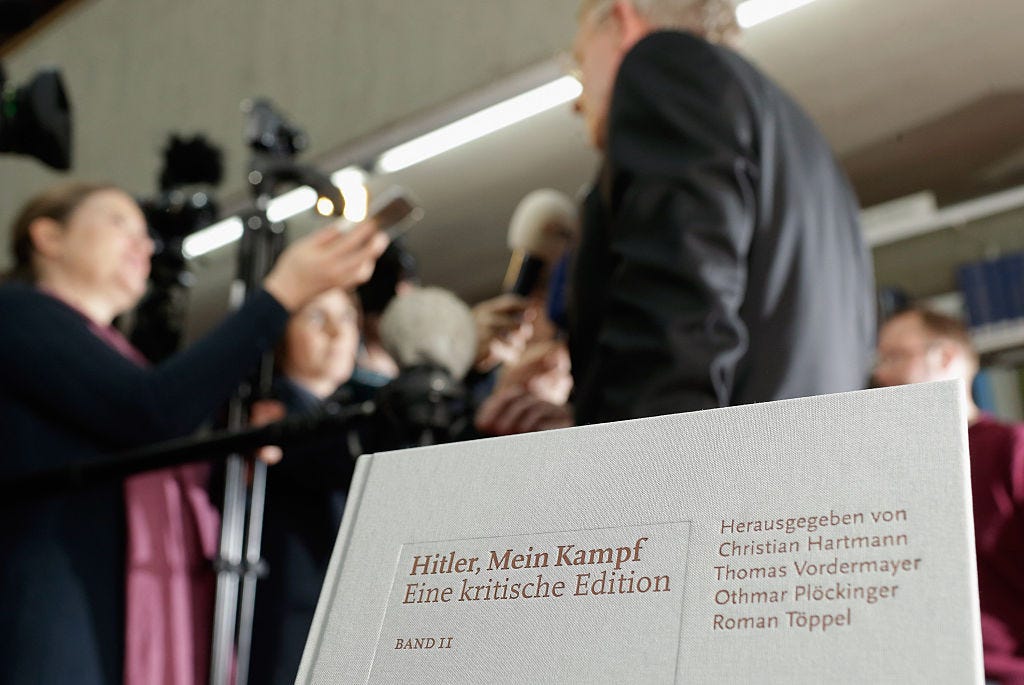

In 2016, Dr. Christian Hartmann published the first new edition of Mein Kampf in Germany since Hitler’s death. His scholarly edition, unfortunately only available in German, presents Mein Kampf in two volumes with critical commentary on nearly every page — the only ethical way to present a book this toxically dishonest and dangerous, he says. It has, however, once again turned the book into a bestseller, having gone through at least nine editions. Houghton Mifflin has continued to donate its royalties from the sales of their book — the same unabridged translation they produced in 1943 after they’d been freed of Hitler’s editorial input — to Jewish and Holocaust-related charities. In 2017, the company would post revenues of $1.41 billion.

As for John Fante and Stackpole and Sons, no reparations were ever made.

A Legacy Lost and Found

“Either the work of John Fante is unknown to you or it is unforgettable. He was not the kind of writer to leave room in between,” the New York Times critic Janet Maslin wrote in 2002. I grew up near Roseville, California, where Fante spent a chunk of his life, and I lived in Downtown LA before they named the square after him. I walked the same streets, dreaming the same dreams of becoming a writer and leaving my mark.

He was unknown to me. Yet, from the first page I read in Ask the Dust, I was hooked and forever changed. It stuns me to think of how nearly I was deprived of this experience — and how thousands of others still are — because of, well, Hitler. To think that Houghton Mifflin, a wonderful publisher of books and textbooks, played a role in that is unbelievable to me.

“The quality of the book has outlasted all the bullshit and that makes me feel good and that makes my dad feel good,” his son, James Fante told me. “Whether he got the recognition while he was alive, I’m not hung up on that and I’m not sure he was either. He had a tremendous amount of confidence about that book. He’s not surprised, wherever he is.”

Yes, the books did find their audience while Hitler died by his own hand in a bunker, above which now sits a forgettable parking lot. Still, the decision to give a platform to Adolf Hitler ended up #NoPlatforming one of America’s greatest writers, nearly permanently so. There is a lesson in that, somewhere, I am sure.

It’s his biographer, Stephen Cooper, who points out that Fante’s is the type of story that sticks with us because it runs from the minutely personal to the sheerly global, from the writer’s war to get his novel read to a literal World War:

John Fante was writing this little personal novel about his alter ego who wants to write stories and be in love, meanwhile the world is about to explode and nations are waiting to invade their neighbors and it’s all going to end with the Atom Bomb. It’s a spectacularly enigmatic layering of story.

It is indeed. one that deserves to be known, so that it is not repeated again.