What hath night to do with sleep?

—John Milton, 1637

Broadway and Forty-Fourth Street, New York City, 1919. The Museum of the City of New York / Art Resource, NY.

In 1924 a young man named Gyula Halász left Brasov, Transylvania—his Hungarian hometown, annexed by Romania in the aftermath of World War I—and moved to Paris. There he began to call himself Brassaï and discovered his vocation as a photographer working in black and white and almost entirely at night.

In an overcoat specially designed with pockets large enough to hold twenty-four glass negatives, and with cigarettes that he used to time the long exposures—“a Gauloise for a certain light, a Boyard if it was darker”—he walked the streets of Paris, its neighborhoods and suburbs, sometimes with his friend Henry Miller but mostly by himself. He knocked on strangers’ doors and asked to take pictures from their windows; he was arrested three times. He returned to his apartment only once the sun rose or when his supply of glass plates ran out.

If, as Diane Arbus said, “a photograph is a secret about a secret,” Brassaï soon discovered which secrets he wanted to tell—confidences revealed (and withheld) about the after-hours lives of raffish Parisians who frequented the low-life cafés, the high-end brothels and cross-dressers’ clubs; about the workers who repaired and maintained the systems that enabled the city to function; about the way that the light from a street lamp illuminated a long deserted staircase descending a hill in Montmartre.

In his introduction to his photography collection The Secret Paris of the ’30s, Brassaï wrote,

Just as night birds and nocturnal animals bring a forest to life when its daytime fauna fall silent and go to ground, so night in a large city brings out of its den an entire population that lives its life completely under cover of darkness…I wanted to know what went on inside, behind the walls, behind the facades, in the wings: bars, dives, nightclubs, one-night hotels, bordellos, opium dens. I was eager to penetrate this other world, this fringe world, the secret, sinister world of mobsters, outcasts, toughs, pimps, whores, addicts, inverts. Rightly or wrongly, I felt at the time that this underground world represented Paris at its least cosmopolitan, at its most alive, its most authentic, that in these colorful faces of its underworld there had been preserved from age to age, almost without alteration, the folklore of its most remote past.

Perhaps this is why so many of my favorite paintings and photographs are night scenes. Brassaï’s photographs. The nocturnes of James McNeill Whistler and Albert Pinkham Ryder. The dark, dramatically lit landscapes of Jean-François Millet and Albert Bierstadt, especially Millet’s painting of men hunting birds by the light of torches throwing off volleys of sparks. The dreamscapes of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, populated as they are by the nightmarish phantasms that live only in darkness. The greatest Caravaggios reimagine Christianity’s most theatrical moments as night scenes—the flagellation of Christ, the conversion of Saint Paul, the martyrdom of Saint Peter, the burial of Saint Lucy—perhaps because the painter was himself nocturnal. His circle included criminals and the neighborhood prostitutes he employed as his models; he belonged to a street gang whose nighttime misadventures culminated in the murder that would compel Caravaggio to spend the last years of his brief life on the run. “I often think that the night is more alive and more richly colored than the day,” Vincent van Gogh once wrote to his sister Willemien. “I definitely want to paint a starry sky now.”

The night painting for which I feel a quasi-religious reverence is a small Sienese panel in tempera and gold: Giovanni di Paolo’s Saint Nicholas of Tolentino Saving a Shipwreck, completed in 1457. The work hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where I have spent many hours; in fact, my superstitious inability to visit the city without making a pilgrimage to see Di Paolo’s painting is so inexplicably powerful that over the years it has affected—and greatly altered—my travel plans.

The Sienese master’s work makes one acutely conscious of the fact that a storm at sea in the night is different from a storm that comes up during the day—and the boat in the painting is very definitely out on the sea at night. The sails have been snapped off by the tempest and are flapping like headless angels in the terrifying black sky. Nine passengers kneel, praying on the deck, and we see their prayers being answered: from the upper right-hand corner, Saint Nicholas comes flying in, dressed in the black robes of his order, one hand raised to calm the storm, the other holding a lily. Beneath the waves that are rocking the boat, a semihuman mermaid-like monster the color of seaweed paddles amid the dark conical underwater mountains.

The painting is so suffused by night, so permeated by the sense of how it feels to be afraid in the darkness, that when you stand in front of it, no other hour seems to exist. You have to remind yourself: outside, it is daytime.

In the hours between midnight and dawn, Paris seemed to Brassaï not only another city but a different world—a “fringe world” with its own climate, its own natural laws, its own geography, denizens, and species. This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly supports the idea: for many of the writers included in these pages, night and day are distinct and disparate worlds. The mystery and excitement that some seek in the darkness is precisely what alarms and repels those who dread it. What’s striking is the intensity and persuasive logic with which these contributors explain (and argue for) which world, night or day, they would choose, if they could, to inhabit for good.

Either way—love it or fear it—the night inspires an unmistakable lyricism. Even the coolly scientific selections border on poetry. Here is the nineteenth-century astronomer

Maria Mitchell on the differences between two stars:

Those who know Sirius and Betel do not at once perceive that one shines with a brilliant white light and the other burns with a glowing red, as different in their brilliancy as the precious stones on a lapidary’s table, perhaps for the same reason. And so there is an endless variety of tints of paler colors. We may turn our gaze as we turn a kaleidoscope, and the changes are infinitely more startling, the combinations infinitely more beautiful; no flower garden presents such a variety and such delicacy of shades.

The explorer Fridtjof Nansen is likewise enchanted by the gorgeous Arctic night: “It is dreamland, painted in the imagination’s most delicate tints; it is color etherealized…it is all faint, dreamy color music, a faraway, long-drawn-out melody on muted strings.”

Such passages evoke the sensation of looking up at the stars at night and experiencing the vastness of the universe, of being made conscious of one’s solitude and one’s insignificance in contrast to that immensity—a feeling that, as this issue makes clear, not everyone enjoys. Gazing up at the starry sky can inspire in some a calm reassurance of oneness with the universe, a thrilling confrontation with the most basic existential questions, while in others it can induce an anxiety bordering on vertigo. Nor does everyone like the idea of what’s out there, in the darkness. A friend who lives in the country installed in her yard a camera with night vision. A lover of animals of every sort, my friend was thrilled by the footage: gigantic eyes and snouts getting larger and larger as the animals approach the camera, peer into the lens, paste their faces on the glass, then turn and scurry away. But the eerie film made me feel queasy and on edge, as if I were watching one of those docu-horror films—a Blair Witch Project sort of thing—with a cast composed entirely of possums and raccoons.

Still others feel that, like the vampires and werewolves a daylight lover may fear, they only really come alive when the lights go out. The thieves and murderers who ply their trade through the pages of this issue can do so only under cover of darkness, and so, as Juvenal and Italo Calvino remind us, more crimes are committed during those blackened hours. Night is said to be Satan’s favorite time; one only has to read John C. Norris’ 1871 account of the nocturnal terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan to be mostly convinced of this. But the dread and the beauty coexist through these nighttime hours. I’ve long admired the opening of Dorothy B. Hughes’ noir novel In a Lonely Place, with its depiction of how the velvety Los Angeles night appears to the serial killer on the prowl for hapless young women—a stark shift in perspective from that of the innocent Angeleno who goes to the beach for the warm salt air and the soothing rhythm of the breaking waves.

An ideal society, in my view, would accommodate both those who prefer the day or the night, to allow people to work during the hours for which they feel predisposed. Some people tire or lose focus at night; others are drawn to the graveyard shift. A friend of mine, a night doorman in Manhattan, says he loves his job. It’s quiet, there are no package deliveries, he has time to write, and the people who come home at three am and chat are in general more interesting than the nine-to-fivers. And I know a doctor, a specialist in emergency medicine, who confesses to being addicted to the adrenaline of the big-city ER at night; how dull are the playground accidents and sore tonsils he sees in the day compared with the gunshot or stab wounds, the severed fingertips he’s been asked to reattach to overworked chefs. Saturday nights are the best, he says. Things can get really crazy. one can hardly picture the two drug-addled holy fools in Denis Johnson’s “Emergency” wanting to—or being allowed to—work at the ER during the daytime. In the clear light of morning, they might find it harder to pilfer pockets full of random pills and to enjoy the high of healing a man whose wife has stuck a hunting knife in his eye.

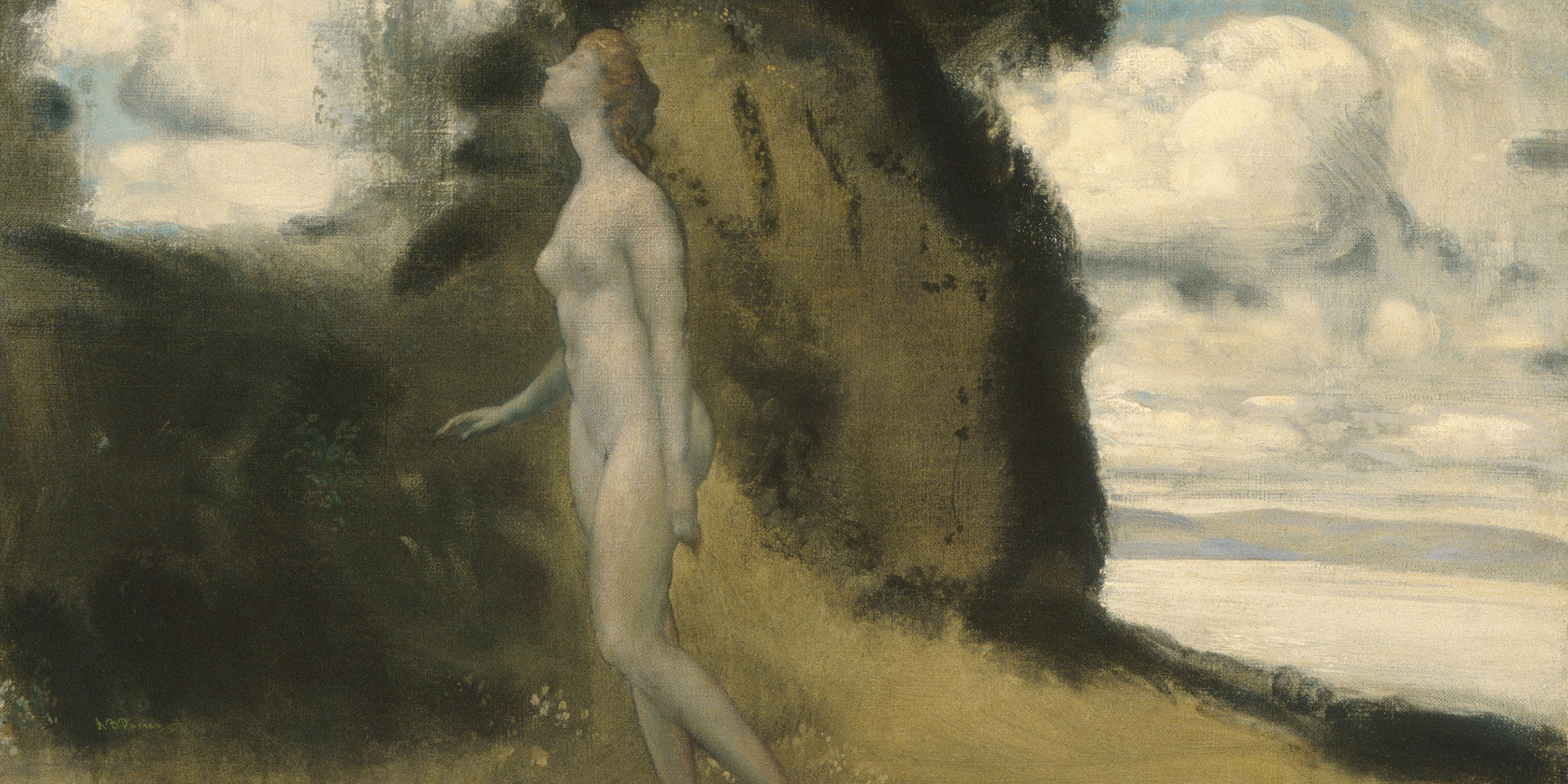

A Measure of Dreams (detail), by Arthur B. Davies, c. 1908. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of George A. Hearn, 1909.

Scattered throughout this issue are accounts of the joys of working at night—provided the work is freely chosen. Quintilian warns us against endangering our health by working past the daylight hours but agrees that “night work, so long as we come to it fresh and untired, provides the best form of privacy.” James Boswell describes the satisfaction of catching up, making amends for his lapses by writing at night in his journal. William Hard captures the giddy freedom of the night messenger boy and the night newsboy; while the good citizens of Chicago sleep, the city belongs to them. Kafka complains, as only Kafka can complain, about the restlessness and insomnia induced by the demands of writing. But we know his great story “The Judgment” was written during the span of a single night, and that—because of the demands of his day job at the Workmen’s Compensation Division—most of his work was done at night. The night man in the all-hours diner interviewed for the WPA Folklore Project admits that he doesn’t want to spend his life “behind this goddamn counter,” but he does like his customers. “I guess I always liked night better than day anyway,” he says.

H.M. Tomlinson celebrates the particular pleasure of finding the perfect book to read in bed: “For though at that hour the body may be dog-tired, the mind is white and lucid, like that of a man from whom a fever has abated. It is bare of illusions. It has a sharp focus, small and starlike, as a clear and lonely flame left burning by the altar of a shrine from which all have gone but one.”

But instead of recognizing that some humans may be either nocturnal or diurnal (or some combination of both, or different at different ages), forces of technology and capitalism have conspired to eliminate the possibility of choice between worlds. The need for profit has little interest in what hours we’d prefer to spend awake or asleep.

For much of the Middle Ages, strict curfews were imposed, and it was forbidden for most workers to labor at night—not to ensure that the populace thrived on restful, restorative sleep but rather because it was feared that any work undertaken by the dim glow of candles and lanterns might be ridden with errors, poorly done. Outdoor illumination was not widely employed until after the 1850s, and the absence meant that the streets belonged, or were thought to belong, to those who were up to no good. This fear of a nocturnal empire of criminality, along with well-founded worries about enemy sieges occurring in darkness and catastrophic fires (such as the Great Fire that gutted London in 1666) started by oil lamps and candles led many cities and towns to establish a night patrol into which its male citizens were conscripted. (Rembrandt’s Night Watch is a group portrait of one such Dutch militia.)

The idea that the night was meant for rest and the day for work changed with the Industrial Revolution, when it began to seem unprofitable and inconvenient to shut the factories down just because it was night. Karl Marx warns his readers that capitalism would increasingly come to view leisure—and sleep—as luxuries that must be dispensed with if workers are to be exploited to the fullest: “In its blind, unrestrainable passion, its werewolf hunger for surplus labor, capital oversteps not only the moral but even the merely physical maximum bounds of the working day. It usurps the time for growth, development, and healthy maintenance of the body.”

![Roman fresco from the “Black Room” in the imperial villa at Boscotrecase, c. 10 [small_cap]bc[/small_cap]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1920 (CC0). Roman fresco from the “Black Room” in the imperial villa at Boscotrecase, c. 10 [small_cap]bc[/small_cap]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1920 (CC0).](https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/sites/default/files/images/artwork/fresco_0.jpg)

Roman fresco from the “Black Room” in the imperial villa at Boscotrecase, c. 10 bc. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1920 (CC0).

Jonathan Crary furthers this idea in his persuasive book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. “Sleep is an uncompromising interruption of the theft of time from us by capitalism,” he argues. “The stunning, inconceivable reality is that nothing of value can be extracted from it.” one way to eliminate (or reduce) the amount of time we sleep—if not the time we need to sleep, then the time we can sleep—would be to alter the balance of day and night: to radically change our circadian rhythms. He describes a (thankfully) failed business venture that sounds like pure science fiction, except that we believe him when he writes,

In the late 1990s a Russian/European space consortium announced plans to build and launch into orbit satellites that would reflect sunlight back onto earth…Each mirror satellite would have the capacity to illuminate a ten-square-mile area on earth with a brightness nearly a hundred times greater than moonlight.

Originally designed to facilitate mining in the Siberian winter darkness, the company “expanded its plans to include the possibility of supplying nighttime lighting for entire metropolitan areas,” pitching its services as “daylight all night long.” After widespread opposition, the project was scrapped, yet it’s disturbing just to imagine the meetings and work sessions at which this idea was discussed and developed. Sleep deprivation is, after all, an effective torture technique. Its victims become disoriented, passive, compliant, emotionally unstable, and, ultimately, physically ill; in perpetual daylight we become a nation—or even a planet—of torture survivors.

Meanwhile, a more gradual and less dramatic version of the move toward nonstop daylight is already taking place in cities throughout the world. The International Dark-Sky Association monitors the disappearing darkness, a phenomenon caused by light pollution, which the group breaks down into four components: glare, sky glow, light trespass, and clutter. The organization tracks the negative effect of light pollution on flora and fauna, from Arctic zooplankton to American toads, and considers how the disruption of our natural circadian rhythm compromises human health. Its website features a “World Atlas of Artificial Night-Sky Brightness” created by an international group of scientists, according to which 80 percent of the world’s population lives under sky glow and 99 percent of the population of the United States and Europe are not at this point able to experience a natural night at all—a terrifying demonstration of how far night has already fallen.

Anyone who doubts how well this could be made to work, how easily darkness could be eliminated, should take a brief walk through Manhattan’s Times Square at night. Illuminated by giant spotlights, searchlights, LED lights, and klieg lights, the neighborhood resembles a film set on which they are shooting a reverse kind of day for night—dressing up night, instead, for day. The glare makes it difficult even to see as far as a city block. Semiblinded by the light, the pedestrians shuffle forward, moving like sleepwalkers, trying just to navigate the sidewalks without bumping into one another.

As a high schooler in New York City in the late 1960s, I often used to lie to my parents about where I was going. Then I hung out with my friends in Times Square—the pregentrified Times Square, the landmark that now exists only on films such as Midnight Cowboy and Taxi Driver. We made our way past the porn theaters, the prostitutes, the junkies and pimps. We ate where they ate—in a restaurant decorated like a Victorian bordello, where you could order a thin but delicious flash-fried steak, a baked potato, and a few green beans, all for $1.99. The bright signs advertising products that can no longer be advertised (that Camel billboard emitting puffs of cigarette smoke) were beautiful and strange. However gritty, Broadway was bright enough, but the side streets, lined with hotels that rented rooms by the hour, were darker, and we loved them, too.

All that ended in the 1990s: Giuliani Time. The porn theaters and peep shows were replaced by Statue of Liberty key chains and i heart ny infant onesies. This was supposedly about crime prevention, but of course the motive was entirely economic. Why would the hordes of tourists thronging the streets spend their hard-earned vacation money exposing the kids to the (low) wages of sex and sin, to the women in glitter hot pants, the boyfriends in ermine-trimmed hats, the scabby theaters showing Deep Throat and The Devil in Miss Jones?

In fact, the ultra-high-definition signs flashing around Times Square now are in their own way very beautiful, especially seen from a vehicle, particularly from a tour bus. But the Times Square that was our Brassaï’s Paris, and in its way our Caravaggio, is now more like a scene from Blade Runner—though considerably more extreme. Being there you begin to understand how it might be possible to eradicate the night entirely.

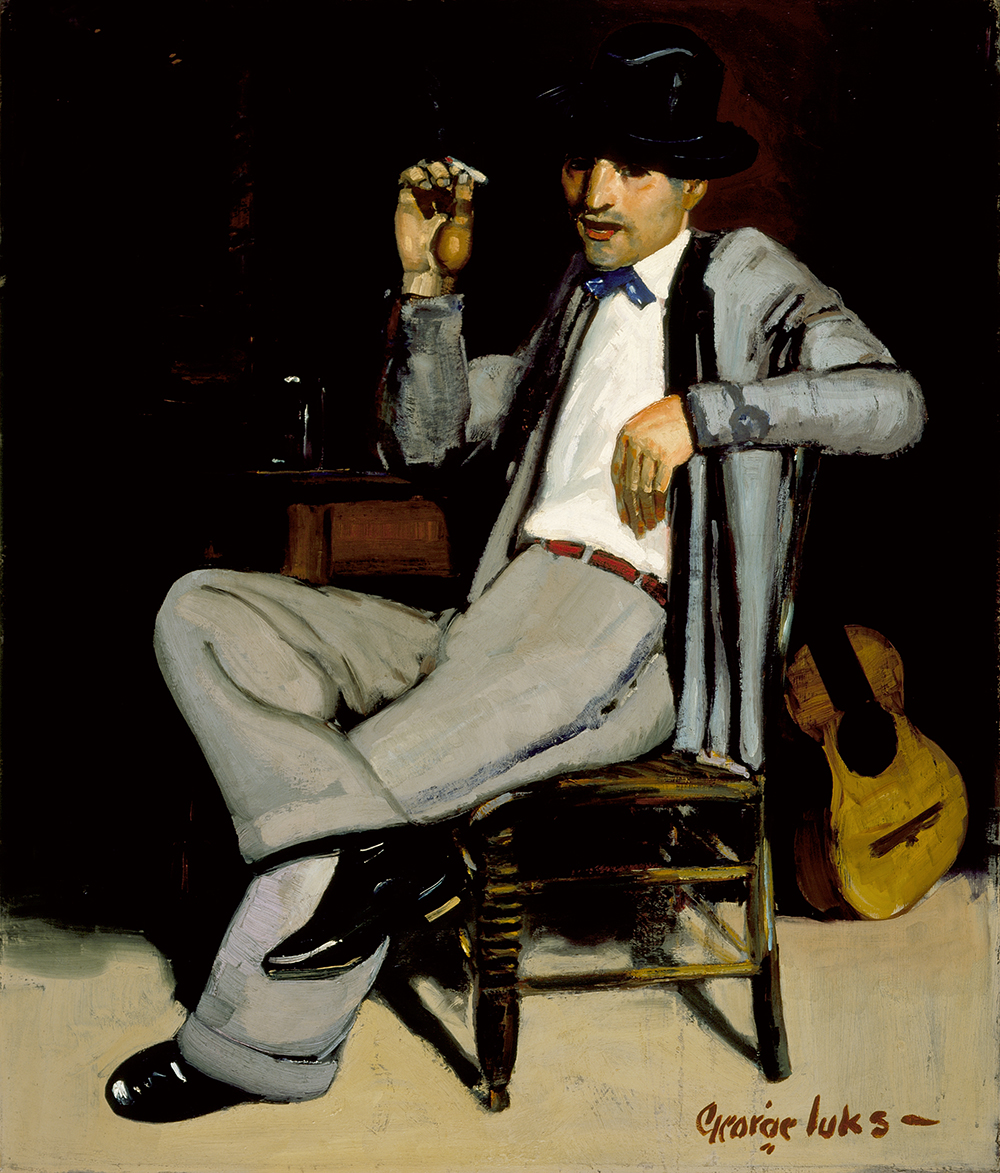

Pedro, by George Benjamin Luks, c. 1920. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. William Preston Harrison Collection.

Would everyone miss it? Probably—even those who struggle hardest with the time when, as F. Scott Fitzgerald writes, “it is always three o’clock in the morning.” Nearly every culture features folktales and superstitions about the goblins, witches, and werewolves that haunt the night. But perhaps these demons are simply metaphors for the dread of the unknown, for the terrors that swarm us when we lie awake in the dark, for the contemplation of his own death that kept Samuel Johnson awake, the “sadness” that overcame Hildegard of Bingen, the “black and monstrous” thoughts that troubled

Schopenhauer, and the terror that Nabokov so eloquently likens to the “black thunder of panic growing.” Philip Larkin’s great 1977 poem “Aubade” is one of literature’s most powerful evocations of the loneliness and horror of lying awake at night, contemplating one’s mortality—and the relief of seeing the first light, the earliest indications that the daily operations of the “uncaring intricate rented world” have resumed.

These thoughts and fears are so understandable, so common, so human. How odd that they don’t much seem to afflict those who love the night rather than dread it. Among the ironies of Larkin’s poem is that the aubade is traditionally a verse form that laments the arrival of dawn and the end of the night—the time when lovers can lie in each other’s arms, a view of the delightful sort of darkness that a reader can find in these pages through Ovid and Sei Shonagon. Even Daniel Genis appreciated night during his incarceration: it’s the only time prisoners, transported from their cells by dreams, can enjoy the illusion of freedom. All this is not so far from the idea, commonly circulated during the Middle Ages, that night was the time most suitable for prayer, a sentiment further echoed by Rainer Maria Rilke: “Shorter are the prayers in bed, but more heartfelt.”

In July 1968 I was invited to celebrate Bastille Day with some friends late at night at an open-air café in Montmartre. When our party ended, long past midnight, there were no taxis to be had, and my friends suggested that I could walk back to my hotel on the Left Bank; it would take no more than half an hour, and all I had to do (I didn’t know Paris well then) was head straight downhill. Eventually I would reach the Seine. I headed for Pigalle, then down a winding cobblestone street that grew darker and more narrow until hardly any light remained. Meanwhile, I began to notice that there were prostitutes in nearly every doorway, some soliciting customers, some chatting with their pimps. I wasn’t alarmed so much as disoriented—not because I was lost or felt threatened but because I felt I had somehow traveled back in time. The streetscape had a dreamlike aura, so much so that when I awoke the next morning in my hotel I wondered if I had imagined my mystifying, out-of-time walk.

It was almost a decade after this trip that I first saw those photographs in Brassaï’s Secret Paris. The images shocked me with their ability to evoke that late-night walk from the Eighteenth Arrondissement. The night in Brassaï’s pictures, taken during the 1920s and 1930s, was the exact kind of night I had witnessed in the early morning hours in the late 1960s after that Bastille Day—a night that, by the time Secret Paris was published in the United States in 1976, had already ceased to exist, and that is by now no longer recognizable in those Paris neighborhoods.

How to appreciate the nights of history, and of our dreams, the darkness that is disappearing from our cities and the city? Luc Sante writes in Low Life, his book on New York City of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, about night as a “bridge to the past, the past that shares the same night as the present, even if it inhabits a different day.” This is the function of the nights one passes through in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. These scenes and theories, stories and invocations, connect us to the pasts of Hesiod and Plutarch, of Shakespeare and Rousseau, of Kafka and Wharton, of Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Bishop, to the dark, mysterious—and now endangered—bridge to our history that must be preserved and protected from the glare, the sky glow, the light trespass, the clutter.

This essay introduces the Winter 2019 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, Night. Lewis H. Lapham will return in the next issue.