Between Knowing and Believing

Can we be certain that what we now think are facts are not merely beliefs?

Like everyone else, I long to know and embrace what is true and trustworthy. Yet as I get older, I have reluctantly come to the view that I know less and believe more – not because I have lapsed into some form of credulity, but rather because much of what I once thought was knowledge now seems to be opinion or belief. It leaves us with the awkward question, which we need to confront honestly: how can we be sure that what we think we now know is not in fact simply a belief? And is the difference between them partly a matter of our location in the historical process?

But let me return to the idyll of my intellectual youth. I was studying the natural sciences at high school, and had set my heart on going to Oxford to study chemistry – in my view, the most interesting and rewarding of the sciences. I loved science partly because of my sense of wonder at the vast complexity of the natural world. I knew what Albert Einstein meant when he spoke of a “rapturous amazement”, and longed to grasp the full truth about this strange yet wonderful world in which I had been placed.

Yet I also loved science because of its passionate quest for truth. I longed for certainty – knowing what was true, rather than believing in half-truths or consoling delusions. I read Plato with the enthusiasm of an amateur, taking pleasure in his distinction between unevidenced opinion or conjecture on the one hand and secure knowledge on the other. Science was the privileged gateway to truth. My decision to focus on science reflected both my longing to make sense of our puzzling universe, and a perhaps deeper, if unacknowledged, yearning for the certainty of simple and stable convictions.

___

"If scientific theories that once commanded widespread support had now been displaced by superior alternatives, who could predict what would happen to these new theories in the future?"

___

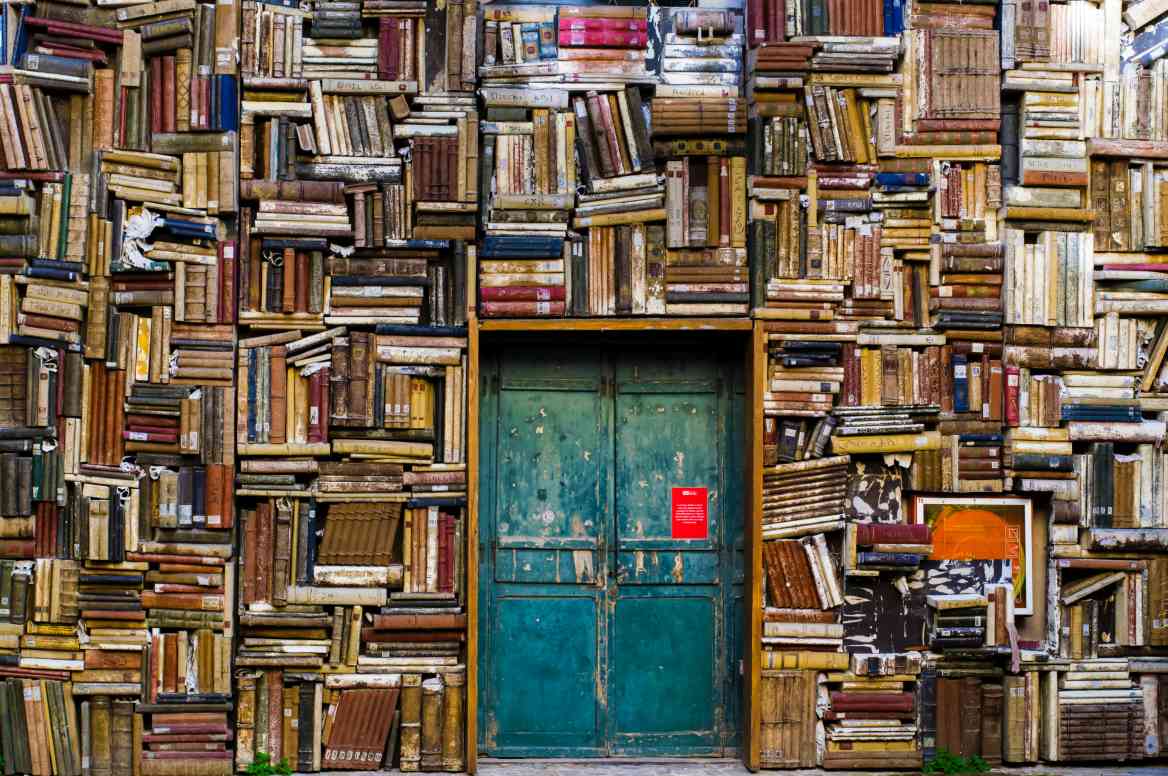

I was thrilled when I won a scholarship to Oxford to study chemistry in December 1970. As Oxford’s chemistry course did not begin until October 1971, I found myself with time on my hands. In that time, I immersed myself in my school’s library, devouring its scientific holdings. After exhausting these, I came across a somewhat grubby bookcase which was labelled “The History and Philosophy of Science.” It was clear few had ever explored its contents. At the time, I regarded this as uninformed criticism of the certainties and simplicities of the natural sciences by people like Karl Popper who felt threatened by them – what Richard Dawkins would later call “truth-hecklers”. How, I wondered, could Popper seriously believe that all scientific “theories are, and remain hypotheses: they are conjecture (doxa) as opposed to indubitable knowledge (episteme).”

However, by the time I had finished reading these volumes, I knew that I would have to do some very serious rethinking. I was experiencing an intellectual epiphany, and scales were falling from my eyes. Suddenly, the world looked very different to me.

Far from being half-witted and uninformed obscurantism that placed unnecessary obstacles in the face of scientific advance, the history and philosophy of science raised legitimate questions about the reliability and limits of scientific knowledge. Issues that were new to me – such as the underdetermination of theory by data, radical theory change in the history of science, the difficulties in devising a “crucial experiment”, the theory-laden character of observation, and the enormously complex issues associated with determining what was the “best explanation” of a given set of observations – complexified what I had hitherto taken to be the simple thoroughly unproblematic question of scientific truth.

It suddenly became clear to me why scientific positivists avoided engaging this material. If scientific theories that once commanded widespread support had now been displaced by superior alternatives, who could predict what would happen to these new theories in the future? These theories might be better than those they had supplanted; but were they right? Might they not be transient staging-posts, rather than final resting places?

I began to realize that certainty of knowledge was rather elusive, seemingly limited to the conceptually interesting though existentially deficient realms of logic and mathematics. When it came to the really big questions of life, proof seemed impossible. one might be able to give good reasons for suggesting that a social or moral belief might be true; yet proof, in the strong and proper sense of that term, seemed to lie beyond reach. Happily, I began to read Bertrand Russell around this time, and found him a source of wisdom as I wrestled with these issues. For Russell, “to teach how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralyzed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing that philosophy, in our age, can still do for those who study it.”

Encouraged by what I read, I explored more of Russell. For Russell, human aspirations to rationality were compromised by the destructive “intellectual vice” of a natural human craving for certainty, which could not be reconciled with the limited capacities of human reason on the one hand, and the complexity of the real world on the other. Philosophy, Russell suggested, was a discipline deeply attuned to this dilemma, enabling reflective human beings to cope with their situation.

___

"The Enlightenment championed the idea of a universal human rationality, valid at all times and places. Yet a more sceptical attitude has increasingly gained sway, seeing this as an essentially political or cultural assertion that certain Eurocentric ways of thinking are universally valid, and hence legitimating the intellectual colonization of other parts of the world, and the suppression of other forms of rationality"

___

I was naïve about these issues, becoming locked into rhetorical assertions about the omnicompetence of science which were not adequately grounded in scientific theorizing or practice. I see this same tendency today amongst those to proclaim the limitless capacity of science to explain everything and deliver certainties about the deepest questions of life. These are actually second-order philosophical statements about science, rather than representing secure empirical deliverances. This scientific imperialism – now usually contracted to “scientism” – finds itself trapped in a viciously circular argument from which no experiment can extricate it, in that it has to assume its own authority in order to confirm it. The insistence on the part of some that all questions be framed scientifically may seem like legitimate science to some, but will be seen as an illegitimate strategy of intellectual colonization by others.

These reflections alerted me to the intellectual provisionality of scientific theorizing, and forced me to draw what I saw as the inevitable but intellectually problematic conclusion that a scientist could commit herself to a theory that she knows might be shown to be wrong in the future. Michael Polanyi’s Personal Knowledge (1958) may have helped me to live with this tension – but it certainly did not resolve it.

Knowledge too often turns out to be a disguised belief. The scientific consensus of the first decade of the twentieth century – regularly presented at that time as secure scientific knowledge – was that the universe was more or less the same today as it always had been. Yet this once fashionable and seemingly reliable view has been eclipsed by the seemingly unstoppable rise of the theory of cosmic origins generally known as the “Big Bang”. What was once thought to be right – and hence to be “knowledge” – was simply an outdated interpretation, an opinion now considered to be wrong.

So is knowledge socially located? To put this another way, is what is deemed “knowledge” in one historical and cultural situation deemed to be “belief” in another? It is an unsettling thought. The American anthropologist Clifford Geertz argued that what we call “common sense” is demonstrably not a universal way of thinking, but is “historically constructed,” varying from one historical location to another. The Enlightenment championed the idea of a universal human rationality, valid at all times and places. Yet a more sceptical attitude has increasingly gained sway, seeing this as an essentially political or cultural assertion that certain Eurocentric ways of thinking are universally valid, and hence legitimating the intellectual colonization of other parts of the world, and the suppression of other forms of rationality. Historical research shows up the existence of multiple forms of rationality in different cultural and historical contexts. They may have been suppressed in the past by the Enlightenment monomyth of a single universal rationality. However, what some are calling “epistemological decolonization” is gaining sway, especially in intellectual circles in South America and southern Africa.

So does this mean that we abandon any hope of finding a rational way of thinking, capable of engaging questions about how our universe functions, and deeper existential questions about meaning, value, and purpose? No. This does not give us any reason to believe what we like. It rather invites us to think more deeply about what it means to be rational. This concern lies behind my recent work The Territories of Human Reason, which explores the historical plurality of cultural rationalities on the one hand, and the diversity of methodologies used in the natural sciences on the other, and tries to understand how a single person can be said to act rationally while holding views that have quite different rational foundations.

For example, consider Albert Einstein, easily one of the most significant thinkers of the twentieth century. Einstein saw no difficulty in holding together his scientific theorizing and socialist political beliefs, despite the fact that political and moral beliefs cannot be considered – contra Engels in the nineteenth century and Sam Harris in the twenty-first century – to have “scientific” foundations. Einstein quite happily worked with several different conceptions of what it meant to be rational, finding ways of knitting them together. Most of us do the same, weaving together scientific, religious, moral and political ideas which come from quite different sources, and which possess quite different rational credentials. These reflections don’t solve the problem, but they at least help us appreciate that challenge that awaits us if we try – like E. O. Wilson – to aim at the “unity of knowledge”.

'學術, 敎育' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Capitalism’s New Clothes (0) | 2019.02.08 |

|---|---|

| The Decline of Historical Thinking (0) | 2019.02.07 |

| How Diderot’s Encyclopedia Challenged the King (0) | 2019.01.31 |

| What Is College Worth? (0) | 2019.01.20 |

| Why Literature Professors Turned Against Authors — Or Did They? (0) | 2019.01.15 |