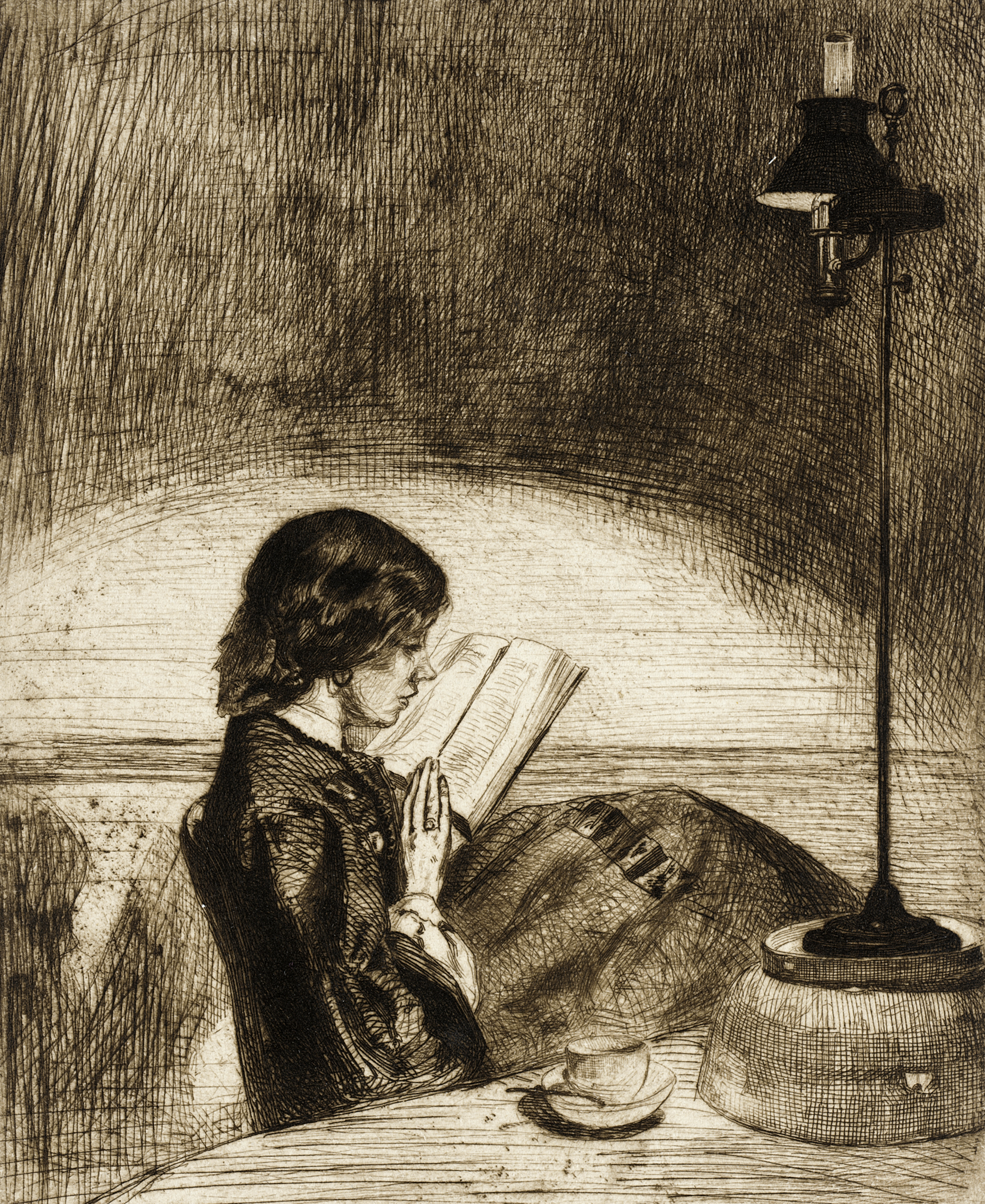

Reading by Lamplight, by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, c. 1853. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Wallace L. De Wolf.

At the beginning of her essay “How Should one Read a Book?”—published in 1932 in the second series of her Common Reader—Virginia Woolf writes, “Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply only to me and not to you.”

The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess. After all, what laws can be laid down about books? The battle of Waterloo was certainly fought on a certain day; but is Hamlet a better play than Lear? Nobody can say. Each must decide that question for himself. To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none.

But to enjoy freedom, if the platitude is pardonable, we have of course to control ourselves. We must not squander our powers, helplessly and ignorantly, squirting half the house in order to water a single rosebush; we must train them, exactly and powerfully, here on the very spot. This, it may be, is one of the first difficulties that faces us in a library. What is “the very spot”? There may well seem to be nothing but a conglomeration and huddle of confusion. Poems and novels, histories and memoirs, dictionaries and bluebooks; books written in all languages by men and women of all tempers, races, and ages jostle each other on the shelf. And outside the donkey brays, the women gossip at the pump, the colts gallop across the fields. Where are we to begin? How are we to bring order into this multitudinous chaos and so get the deepest and widest pleasure from what we read?

Here is a less than exhaustive set of beginnings from Woolf’s own life of reading, found in her literary criticism, books, letters, and diaries.

Cookbooks

“Independent of the knowledge they convey, cookery books are delightful to read,” Woolf—then still Ms. Stephens—wrote in a 1909 Times Literary Supplement review of The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tallybronie.

A charming directness stamps them, with their imperative, “Take an uncooked fowl, and split its skin from end to end”; and their massive common sense which stares frivolity out of countenance. Then, apart from the wonderful suggestive power of the words they deal in—Southdown mutton, hares, jugged venison, fresh strawberries—it is pleasant to think of herbs growing on moors, hares running in the stubble, spices brought with bales of embroidery from the Indies; and the strings of words themselves often have a beauty such as poets aim at.

“Strain it and sweeten to taste with sugar honey or candied Eringo root…add a few cloves, whole pepper, salt, a bay leaf, a sprig of thyme, one of marjoram, and some parsley…Then a finger-glass and rose and orange water poured over the guests’ hands.”

Leonard Woolf

On January 31, 1915, shortly after tea, Virginia starting reading her husband’s second novel, The Wise Virgins. She finished it just before bed and recorded her very honest review of it in her diary.

My opinion is that it’s a remarkable book; very bad in parts; first-rate in others. A writer’s book, I think, because only a writer perhaps can see why the good parts are so very good, and why the bad parts aren’t very bad. I was made very happy by reading this.

Henry James

“All great writers have, of course, an atmosphere in which they seem most at their ease and at their best,” Woolf wrote in a Times Literary Supplement review of James’ posthumously published and unfinished autobiography The Middle Years in October 1917, “a mood of the great general mind which they interpret and indeed almost discover, so that we come to read them rather for that than for any story or character or scene of separate excellence.”

For ourselves Henry James seems most entirely in his element, doing that is to say what everything favors his doing, when it is a question of recollection. The mellow light which swims over the past, the beauty which suffuses even the commonest little figures of that time, the shadow in which the detail of so many things can be discerned which the glare of the day flattens out, the depth, the richness, the calm, the humor of the whole pageant—all this seems to have been his natural atmosphere and his most abiding mood.

Twenty days before her death by suicide on March 28, 1941, Woolf wrote in her diary, “I intend no introspection. I mark Henry James’ sentence: Observe perpetually. Observe the oncome of age. Observe greed. Observe my own despondency. By that means it becomes serviceable. Or so I hope. I insist upon spending this time to the best advantage.”

Joseph Conrad

“Mr. Conrad’s genius is a very complex one,” Woolf wrote in a Times Literary Supplement review of Lord Jim published in July 1917. “Although his characters remain almost stationary they are enveloped in the subtle, fine, perpetually shifting atmosphere of Marlow’s mind; they are commented upon by that voice which is so full of compassion, which has so many deep and fine cadences in its scale.”

Mr. Conrad has told us [in A Personal Record] that it is his conviction that the world rests on a few very simple ideas, “so simple that they must be as old as the hills.” His books are founded upon these large and simple ideas; but the texture through which they are seen is extremely fine; the words which drape themselves upon these still and stately shapes are of great richness and beauty. Sometimes, indeed, we feel rather as if we were lying motionless between sea and sky in that atmosphere of profound and monotonous calm which Mr. Conrad knows so strangely how to convey. There is none of the harassing tumult and interlocking of emotion which whirls through a Dostoevsky novel, and to a lesser extent provides the nervous system of most novels. The sea and the tropical forests dominate us and almost overpower us; and something of their largeness, their latent inarticulate passion seems to have got into these simple men and these old sea captains with their silent surfaces and their immense reserves of strength.

Fyodor Dostoevsky

“In reading him,” Woolf wrote in a TLS review of Dostoevsky’s The Eternal Husband and Other Stories in February 1917, “we are often bewildered because we find ourselves observing men and women from a different point of view from that to which we are accustomed.” She explained,

We have to get rid of the old tune which runs so persistently in our ears, and to realize how little of our humanity is expressed in that old tune. Again and again we are thrown off the scent in following Dostoevsky’s psychology; we constantly find ourselves wondering whether we recognize the feeling that he shows us, and we realize constantly and with a start of surprise that we have met it before in ourselves, or in some moment of intuition have suspected it in others. But we have never spoken of it, and that is why we are surprised.

James Joyce

On September 6, 1922, after days of grumbling about it in her diary, Woolf finished Joyce’s Ulysses.

Genius it has I think, but of the inferior water. It is underbred, not only in the obvious sense, but in the literary sense. A first-rate writer, I mean, respects writing too much to be tricky; startling; doing stunts. I’m reminded all the time of some callow bored schoolboy, full of wits and powers, but so self-conscious and egotistical that he loses his head, becomes extravagant, mannered, uproarious, ill at ease, makes kindly people feel sorry for him, and stern ones merely annoyed; and one hopes he’ll grow out of it; but as Joyce is forty this scarcely seems likely. I have not read it carefully; and only once, and it is very obscure; so no doubt I have scamped the virtue of it more than is fair. I feel that myriads of tiny bullets pepper one and spatter one; but one does not get one deadly wound straight in the face—as from Tolstoy, for instance, but it is entirely absurd to compare him with Tolstoy.

After Leonard gave her an “intelligent” review of Ulysses from The Nation, she slightly revised her opinion of the book. “Still I think there is a virtue and some lasting truth in first impressions; so I don’t cancel mine,” she wrote in her diary a day later.

Charlotte Brontë and Jane Austen

In the first series of The Common Reader, from 1925, Woolf thought about what Charlotte Brontë could have written if she had lived just a little longer.

She might have become like some of her famous contemporaries, a figure familiarly met with in London and elsewhere, the subject of pictures and anecdotes innumerable, the writer of many novels, of memoirs possibly, removed from us well within the memory of the middle-aged in all the splendor of established fame.

She might have been wealthy, she might have been prosperous. But it is not so. When we think of her we have to imagine someone who had no lot in our modern world; we have to cast our minds back to the Fifties of the last century, to a remote parsonage upon the wild Yorkshire moors. In that parsonage, and on those moors, unhappy and lonely, in her poverty and her exaltation, she remains forever.

And she wondered what would have happened in the six novels Jane Austen would never write in an essay first published in The New Republic in 1924.

She would not have written of crime, of passion, or of adventure. She would not have been rushed by the importunity of publishers or the flattery of friends into slovenliness or insincerity. But she would have known more. Her sense of security would have been shaken. Her comedy would have suffered. She would have trusted less (this is already perceptible in Persuasion) to dialogue and more to reflection to give us a knowledge of her characters. Those marvelous little speeches which sum up, in a few minutes’ chatter, all that we need in order to know an Admiral Croft or a Mrs. Musgrove forever, that shorthand, hit-or-miss method which contains chapters of analysis and psychology, would have become too crude to hold all that she now perceived of the complexity of human nature. She would have devised a method, clear and composed as ever, but deeper and more suggestive, for conveying not only what people say, but what they leave unsaid; not only what they are, but what life is. She would have stood farther away from her characters, and seen them more as a group, less as individuals. Her satire, while it played less incessantly, would have been more stringent and severe. She would have been the forerunner of Henry James and of Proust—but enough. Vain are these speculations: the most perfect artist among women, the writer whose books are immortal, died “just as she was beginning to feel confidence in her own success.”

William Hazlitt

“There can be no question that Hazlitt the thinker is an admirable companion,” Woolf wrote in the second series of her Common Reader.

He is strong and fearless; he knows his mind and he speaks his mind forcibly yet brilliantly too, for the readers of newspapers are a dull-eyed race who must be dazzled in order to make them see. But besides Hazlitt the thinker there is Hazlitt the artist…Hazlitt felt with the intensity of a poet. The most abstract of his essays will suddenly glow red-hot or white-hot if something reminds him of his past. He will drop his fine analytic pen and paint a phrase or two with a full brush brilliantly and beautifully if some landscape stirs his imagination or some book brings back the hour when he first read it.

She had previously written that he “was not one of those noncommittal writers who shuffle off in a mist and die of their own insignificance” when reviewing his essays in the TLS in September 1930.

His essays are emphatically himself. He has no reticence and he has no shame. He tells us exactly what he thinks, and he tells us—the confidence is less seductive—exactly what he feels. As of all men he had the most intense consciousness of his own existence, since never a day passed without inflicting on him some pang of hate or jealousy, some thrill of anger or pleasure, we cannot read him for long without coming in contact with a very singular character—ill-conditioned yet high-minded; mean yet noble; intensely egotistical yet inspired by the most genuine passion for the rights and liberties of mankind. Certainly, no one could read Hazlitt and maintain a simple and uncompounded idea of him.

Shortly before the review appeared, Woolf wrote in her diary that when it came to Hazlitt, she was “not sure that I have speared that little eel in the middle—which is one’s object in criticism.”

D.H. Lawrence

“I am reading D.H. Lawrence with the usual sense of frustration,” Woolf wrote in the October 2, 1932, entry in her diary.

I don’t escape when I read him; what I want is to be made free of another world. This Proust does. To me Lawrence is airless, confined: I don’t want this, I go on saying. And the repetition of one idea. I don’t want that either. I don’t want “a philosophy” in the least. I don’t believe in other people’s reading of riddles.

Vera Brittain

“I am reading with extreme greed a book by Vera Brittain called The Testament of Youth,” Woolf wrote in her diary on September 2, 1933.

Not that I much like her. But her story, told in detail, without reserve, of the war, and how she lost lover and brother, and dabbled her hands in entrails, and was forever seeing the dead, and eating scraps, and sitting five on one WC, runs rapidly, vividly across my eyes. A very good book of its sort. The new sort, the hard anguished sort, that the young write; that I could never write. Nor has anyone written that kind of book before. Why now? What urgency is there on them to stand bare in public? She feels that these facts must be made known, in order to help—what? Herself partly I suppose. And she had the social conscience. But I give her credit for having lit up a long passage to me at least. I read and read and read.

Sophocles

“Reading Antigone,” Woolf wrote in her diary on October 29, 1934. “How powerful that spell is still—Greek. Thank heaven I learnt it young—an emotion different from any other.”

Geoffrey Chaucer

“Read Chaucer,” she wrote in her diary on April 29, 1939. “Enjoyed it. Was warm and happy.”

Before her death, Woolf was working on a book with the working title Reading at Random, an expansive history of English literature, starting before Chaucer, skipping the present, and ending in the future. She read G.M. Trevelyan’s History of England for research and probably descended back into other books she had read before, as well as many new to her. “I am almost—what d’you call a voracious cheese mite which has gnawed its way into a vast Stilton & is intoxicated with eating as I am with reading history, & writing fiction & planning—oh such an amusing book on English literature,” she wrote to Ethel Syth on November 14, 1940.

William Shakespeare

June 22, 1940, was a “heavy gray day,” and Woolf was “depressed and irritated.” Nightly raids kept happening in London; people kept dying.

I would like to find one book and stick to it. But I can’t. I feel, if this is my last lap, oughtn’t I to read Shakespeare? But can’t. This, I thought yesterday, may be my last walk. The corn was flowing with poppies in it. And I read my Shelley at night.

She wrote often about Shakespeare in her diary. “By the way,” she wrote in August 1924, “why is poetry wholly an elderly taste?”

When I was twenty I could not for the life of me read Shakespeare for pleasure; now it lights me as I walk to think I have two acts of King John tonight, and shall next read Richard the Second. It is poetry that I want now—long poems. I want the concentration and the romance, and the words all glued together, fused, glowing: have no time to waste any more on prose.

For a look at more reading ideas and suggestions, see the other entries in our reading list series: Frederick Douglass, Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roosevelt, Nella Larsen, Flannery O’Connor, and Emily Dickinson.