While nowadays he might be best known for the cut of meat that bears his name, François-René de Chateaubriand was once one of the most famous men in France — a giant of the literary scene and idolised by such future greats as Alphonse de Lamartine and Victor Hugo. Alex Andriesse explores Chateaubriand’s celebrity and the glimpse behind the public mask we are given in his epic autobiography Memoirs From Beyond the Grave.

In the spring of 1816, Alphonse de Lamartine was restless, ambitious, and twenty-five years old. Four years later, with the publication of his Méditations poétiques, he would be the toast of Paris, but for the moment he was just another provincial scribbler in the capital, too shy and proud, he says in his memoirs, to set foot in a literary salon. He therefore decided he would do the next best thing. He would travel four miles to the south, to the leafy Vallée aux Loups, and roam the forest, hoping to catch sight of one of the “great living figures of our era.”1

This figure was François-René de Chateaubriand. A Bourbon royalist, a Catholic apologist, and the author of several popular books (including the novels Atala and René), Chateaubriand held a fascination for his contemporaries hard for us to understand. His fiction, which we often find high-flown and formal, they experienced as daring and wild; his conservative politics, which some of us regard with suspicion, were appreciated for being admirably idiosyncratic. Chateaubriand may have coined the word “conservative” in the political sense (by titling the Bourbonist journal he edited Le Conservateur), but he was also, in Anka Muhlstein’s words, “a liberal, open to modernity” (modernité being another word he is said to have coined).2

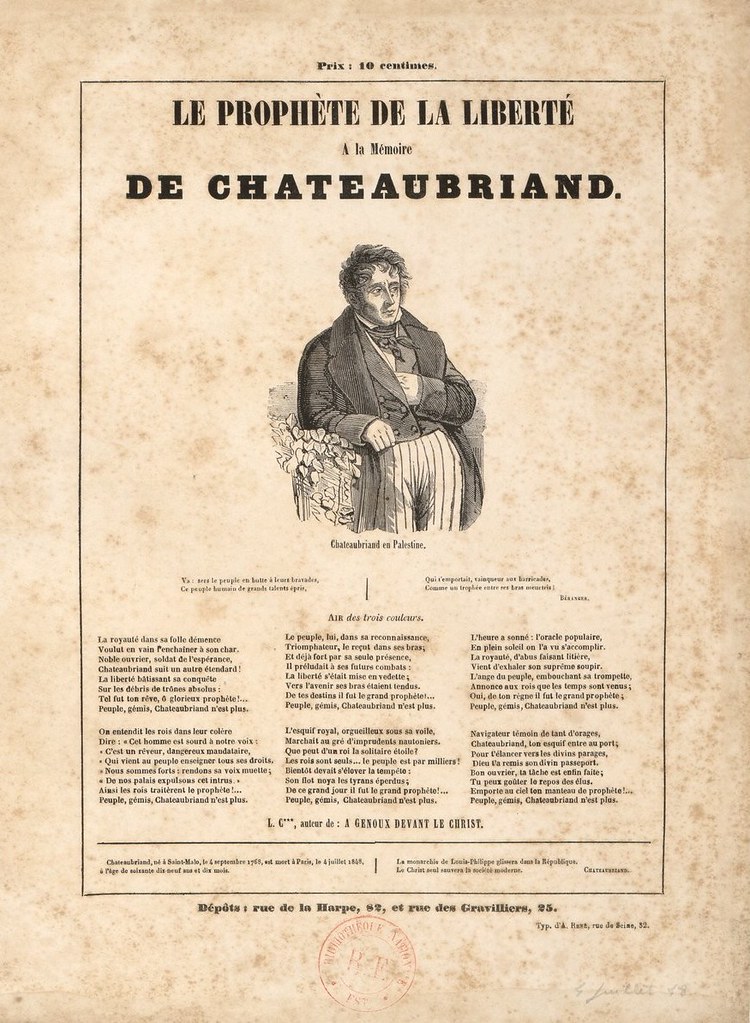

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, the French public looked to Chateaubriand as a man of principle, a defender of the freedom of the press, and an independent thinker unafraid to criticize both the tyrannical Napoleon and the disappointing Bourbon king Louis XVIII. In 1830, a few days before he resigned his seat in the Chamber of Peers — refusing to swear allegiance to the “usurping” king Louis-Philippe — a group of university students spotted him in the street and spontaneously hoisted him onto their shoulders, chanting “Long live freedom of the press! Long live Chateaubriand!” Yet, following his death in 1848, the reasons for his reputation soon grew vague. The entry for Chateaubriand in Gustave Flaubert’s Dictionary of Accepted Ideas, a book of bourgeois bromides compiled in the 1870s, might as well have been written yesterday: “Best known for the cut of meat that bears his name.”3

Back in the 1810s, no one would have associated Chateaubriand with sirloin. He was famous and subject to fame’s magnifying lens. “I want to be Chateaubriand or nothing”,4 the fourteen-year-old Victor Hugo wrote in his diary, only a month or two after Lamartine, that fanboy avant la lettre, had gone to skulk around Chateaubriand’s house in the Vallée aux Loups. Adolescent identification with this tragic master of melancholy — who’d spent seven years of the 1790s exiled in England while several members of his family were guillotined under the Reign of Terror — drove many young romantics to a kind of madness, although none, so far as I know, acted on their madness with as much fervor as Lamartine.

Wandering the Vallée aux Loups, Lamartine found Chateaubriand’s house easily enough. He was unable to see anything over the garden wall, however, and so he climbed into some trees overlooking the property. “I stayed sitting in the branches, hidden by the leaves, from noon until night, but to no avail”, he recalls in his memoirs; “I saw nothing moving except a trickle of water that sparkled as it sputtered from a stucco fountain, and the shadows that shifted and spread over the grass beneath the weeping willows.”5 When night fell, Lamartine was forced to return to Paris. But he had not abandoned his folly. By noon the next day, he was back, like Calvino’s baron, in his perch among the branches:

Half the afternoon elapsed in the same silence and disappointment as the afternoon before. Finally, at sunset, the door of the little house turned slowly and noiselessly on its hinges. A short man in black clothes, with broad shoulders, skinny legs, and a noble head, emerged, followed by a cat, to whom he threw balls of bread to make it gambol on the grass. Soon, both cat and man were swallowed by the shadows of an alley of trees; the undergrowth hid them from my sight. A moment later, the black clothes reappeared at the threshold of the house, and locked the door. This was all I saw of the author of René, but it was enough to satisfy my poetic superstitions. I went back to Paris dizzy with literary glory.6

In later life, Lamartine’s fervor for Chateaubriand inevitably cooled. He could no longer see what had once excited him in the writing, which he now found too theatrical (“always treading the boards”).7 As for the man, Lamartine would be introduced to him several times in the embassies and palaces of Paris, London, and Rome. “But the Chateaubriand of the Vallée aux Loups has for me always been the real Chateaubriand”, he concluded: “The person, rather than the persona.”8

Like every celebrity, from Virgil to Marilyn Monroe, the “real” identity of Chateaubriand was an object of speculation. Readers approached him expecting to find the living embodiment of his books, and Chateaubriand, for his part, made an effort to oblige. “He is too grave and serious”, the American scholar George Ticknor wrote in his diary after dining with Chateaubriand at a soirée held on May 28, 1817,

and gives a grave and serious turn to the conversation in which he engages; and even when the whole table laughed at Barante’s wit, Chateaubriand did not even smile; — not, perhaps, because he did not enjoy the wit as much as the rest, but because laughing is too light for the enthusiasm which forms the basis of his character, and would certainly offend against the consistency we always require.9

Consistency of character was a tenet of the nineteenth-century belief in “great men”, whose conduct never wavered, but even if the culture encouraged such consistency, Chateaubriand took it to extremes. Amélie Lenormant (the niece and adopted daughter of Chateaubriand’s longtime mistress and renowned salon hostess Madame Récamier) observed that, by placing him on a pedestal, Chateaubriand’s admirers “often put him in the awkward position of striking a pose.”

When there were no strangers present, and he was alone with people he liked, and of whose affection he was certain, he gave himself up to his true nature and became entirely himself. His animated conversation, which often edged into eloquence, his cheerful witticisms, and his hearty laughter made his company incomparably delightful. In private, no one was so easygoing and childlike, if I may use this word in speaking of a man whose genius and character inspired so much respect. But all it took was the presence of a stranger, or sometimes a single word, to make him resume his Great Man’s mask and his stiffness of manner.10

The mask that Chateaubriand wore to face the public was not meant to be charming; it was meant to be impressive, in keeping with the impressive principles he’d pledged to uphold. George Ticknor — calling on Chateaubriand at his home a few days after the formal dinner during which His Eminence had appeared so humorless — was surprised to find him relaxed enough to chat candidly about a bad review while playing with his cat “as simply as ever Montaigne did”.11 But this sense of surprise may tell us more about the naivety of Ticknor than the personality of Chateaubriand, who wrote in his Memoirs from Beyond the Grave: “Do you think I’m stupid enough to believe that my nature has changed because I’ve changed my clothes?”12 If Chateaubriand could be pompous, bombastic, and vain, he could also — at least once he had closed the door on the world outside — laugh at the absurdities of existence with the best of them.

In Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, the more than two-thousand-page autobiography he composed between 1803 and 1847, Chateaubriand allowed himself to drop his great man’s mask at length. Although the Memoirs are often looked upon as a historical document, they are more than that: they’re a masterwork of literary style as the expression of sensibility — an exploration, in the tradition of Montaigne’s Essays, of the moods and memories of an individual mind. Abridgements of the work, which boil it down to “essentials”, do readers a disservice by eliminating Chateaubriand’s digressions, which are precisely what give the work its zest. Sainte-Beuve was the first in a long line of practical-minded critics to complain of these digressions: “At the most critical and decisive moments, he turns into a dreamer and starts talking to swallows and crows in the trees along the road.”13 But the Memoirs are not always about what they claim to be about. The Old Regime, the Revolution, the Empire, the Restoration, the July Monarchy — all of these form a backdrop for the book’s central subject, which is the author himself.

Chateaubriand had originally intended Memoirs from Beyond the Grave to be published fifty years after his death. However, when he resigned from the Chamber of Peers in 1830, he forfeited his government pension. By 1834, he was broke. Madame Récamier came to his rescue, arranging for readings of the Memoirs at her house and publication of excerpts from them in journals. She even helped organize a society of shareholders whose payments — investments in the Memoirs’ future sales — would provide Chateaubriand with a modest annuity to the end of his days. The formation of this society also placed the Memoirs out of Chateaubriand’s legal control. In his last years, he was pained to realize the autobiography he’d regarded as private would be published the moment he died, in order to generate profits for shareholders. This was far from the glorious future he had imagined for his work.

The end of Chateaubriand’s life was harrowing. Immobilized by rheumatism, suffering bouts of neuralgia and vertigo, he was vulnerable to the swarm of Boswells who surrounded him. These ranged from his secretary Julien Danièlo — who published a worshipful and paranoid book called Conversations with Monsieur de Chateaubriand: Against His Accusers (1864)14 — to Victor Hugo and Alexis de Tocqueville. Hugo, who had long ago given up wanting to be Chateaubriand, wrote in detail of the elderly man’s physical decline and of his daily visits with Madame Récamier, at her house a few blocks away:

By early 1847, Monsieur de Chateaubriand was a paralytic and Madame Récamier was blind. Every day, at three in the afternoon, Monsieur de Chateaubriand was carried to Madame Récamier’s bedside. The scene was touching and sad. The woman who could no longer see fumblingly stretched out her hands to the man who could no longer feel; their hands met. God be praised! Life was dying, but love still lived.15

Tocqueville, Chateaubriand’s nephew and friend, chronicled the “sort of speechless stupor” that, during his final months, in 1848, “sometimes led us to believe his mind had gone”.

Yet, while in this state, he heard the rumble of the February Revolution and wanted to know what was happening. He was told that they had just overthrown Louis-Philippe’s monarchy. He said, “Well done!” and fell silent again. Four months later, the noise of the June days reached his ear and again he asked what it was. We told him that there was fighting in Paris and he was hearing gunfire. At this, he made futile efforts to stand up, saying: “I want to go there and see.” Then he fell quiet, and this time forever, for he died the next day.16

The day after Chateaubriand died, on the fifth of July, Hugo paid a visit to the death chamber, criticized the bedstead (“of rather doubtful taste”), described the corpse, and inventoried the room with an exactitude that, depending on one’s point of view, either attests to Hugo’s stylistic clarity or to his love of cleanliness and fine décor. He was especially horrified to learn that the forty-eight notebooks containing the Memoirs were “in such disorder…that one of them had been found that very morning in a dark and dirty corner where the lamps were cleaned.”17

Chateaubriand’s last years were so well documented, it may come as no surprise that even his barber wrote a memoir about him. The book, titled (what else?) Chateaubriand’s Barber, by Adolphe Pâques, is of limited interest, even if Pâques — who not only cut his client’s hair, but shaved him daily — does paint a memorable picture of Chateaubriand in the years before he was confined to bed:

I can still see him sitting in a big armchair. on his left is the fireplace, where a bright fire used to crackle in every season, for he was very prone to chills. on his right was a table piled with papers, books, and political and literary journals of every size and hue — all of it pell-mell and in an admirable disorder. I was permitted to take whatever journals I liked from the pile, and every day I carried off three or four to the greatest satisfaction of the clients at my shop. The kettle containing the shaving water sloshed around before the hearth. I shaved him on the spot. I have already spoken of the simplicity of the great writer’s tastes; the frockcoat he used as a housecoat was threadbare; its lapels made very clear, to anyone who was not already aware, that the porter’s breakfast must have been chocolate.18

More interesting to consider are the two pictures Pâques painted using Chateaubriand’s own hair, which he had saved for years in a wooden box before — during his retirement and long after Chateaubriand’s death — he daubed and arranged it in such a way as to represent, on one canvas, the room in which Chateaubriand was born and, on another, the tomb in which he was buried. The idea of painting with a dead man’s hoarded hair is ghoulish. Still, one has to admit the results are not half bad.

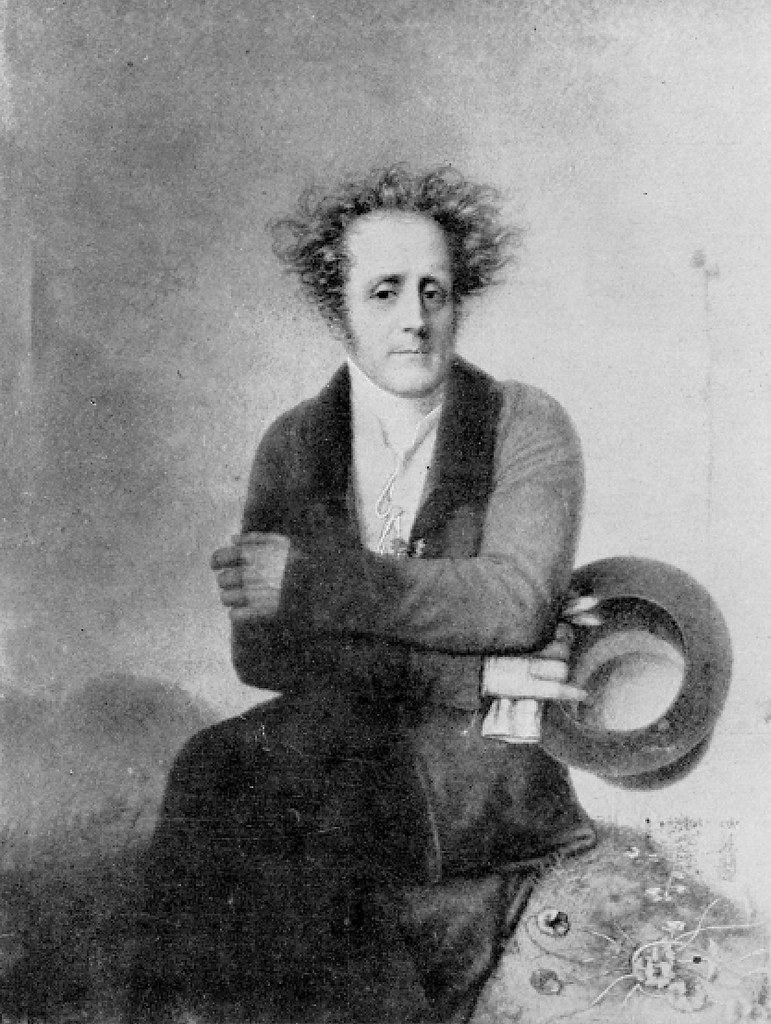

Chateaubriand’s fame ensured he would be documented by any number of writers and portrayed by any number of artists. But he did not think highly of any of the portraits made during his lifetime. He believed they bore him no resemblance because the portraitists had proceeded from an idea of who he was which had little to do with reality: “The crowd”, he writes in Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, “is too frivolous, too inattentive to give themselves the time, unless they’ve been warned beforehand, to see individuals as they are.”19

The smiling public man — or rather the glowering public man — is certainly what we see in the well-known portrait by Girodet. The Roman ruins in the background, the heroic pose, and the far-off stare keep the viewer at arm’s length. The only portrait I’ve come across that suggests something of the author we meet in the Memoirs is a pencil drawing by Hilaire Ledru done in 1820, when Chateaubriand was in his early fifties. Here, again, he has been posed, but his crossed arms and cautiously amused expression intimate a wry melancholy, obscurely reinforced by the gloves and the open shell of the top hat he holds in his right hand.

The images of Chateaubriand as seen by others are intriguing for the insight they give us, especially into the role he played in the collective imagination of early nineteenth-century France. The Memoirs, on the other hand, are a self-portrait, almost cubist in their complexity, dominated by shadows, contradictions, and doubts. Chateaubriand, like his contemporaries, may have imagined he was destined to be remembered for having defended tradition, poeticized religion, and served the nation of France. As it turned out, though, his greatest gift was for translating personhood into prose. His masterpiece was the private life.

Alex Andriesse received his doctorate in English literature from Boston College in 2013. His writing has appeared in Granta, 3:AM Magazine, and The Millions. His ongoing translation of Chateaubriand’s Memoirs from Beyond the Grave — the first volume of which appeared in 2018 — is published by NYRB Classics.

1. Alphonse de Lamartine, Cours familier de littérature: un entretien par mois, vol. 2 (Paris: Self-Published, 1856), 250. All French texts translated by Alex Andriesse, unless otherwise indicated.↩

2. Anka Muhlstein, introduction to Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, 1768–1800, trans. Alex Andriesse (New York: NYRB Classics, 2018), xvii.↩

3. Gustave Flaubert, A Dictionary of Accepted Ideas, trans. Jacques Barzun (New York: New Directions, 1967), 23.↩

4. Adèle Hugo, Victor Hugo raconté par un témoin de sa vie, vol. 2 (Paris: Société d’éditions littéraires et artistiques, Librairie Paul Ollendorff, 1926), 6.↩

5. Lamartine, Cours familier, 253.↩

6. Lamartine, Cours familier, 254.↩

7. Lamartine, Cours familier, 254. There appears to be no small amount of stagecraft in Lamartine’s own story of spying on Chateaubriand. The woodsy romantic setting and the cat (le chat) bounding at his side like a warlock’s familiar seem too perfect to be true.↩

8. Lamartine, Cours familier, 254.↩

9. George Ticknor, Life, Letters, and Journals of George Ticknor (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1878), 1:137.↩

10. Amélie Lenormant, Souvenirs et correspondance tirés des papiers de Madame Récamier (Paris: Michel Lévy, 1859), 2:438.↩

11. Ticknor, Life, 139.↩

12. Chateaubriand, Memoirs, 242.↩

13. Sainte-Beuve quoted in Muhlstein, Memoirs, xviii.↩

14. Julien Danièlo, Conversations de M. de Chateaubriand: Ses agresseurs (Paris: E. Dentu, 1864).↩

15. Victor Hugo, Choses vues (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1900), 208.↩

16. Alexis de Tocqueville, Souvenirs (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1893), 255.↩

17. Victor Hugo, Choses vues, 205.↩

18. Adôlphe Paques, Le coiffeur de Chateaubriand (Rennes: La Découvrance, 1872; reprinted in 1998), 151–152.↩

19. Chateaubriand, Memoirs, 462.↩