In the 1850s, when he was in his early 20s, John Beasley Greene packed up his equipment and headed to Egypt. From Alexandria, the young photographer lugged his supplies onto a ship bound for Cairo, and then transferred to a smaller, private vessel that could navigate the Nile’s cataracts. Greene, born in France to wealthy American parents, would go on to visit Egypt twice in total—each time, training his lens on monumental structures, sweeping swaths of desert, and the go-on-forever sky.

He wasn’t the first European to apply the nascent medium of photography to Egypt’s then-moldering monuments, date palms, and riverside views. At least two others had beat him to it: Maxime Du Camp (who traveled with Gustave Flaubert) and Félix Teynard had made separate trips just a few years before.

Unlike Du Camp and Teynard, Greene had begun taking photos before his trips to Egypt, and kept at it afterward, writes Corey Keller, curator of photography at SFMOMA, in Signs and Wonders: The Photographs of John Beasley Greene. (An exhibition of Greene’s work is on view at the museum through January 5, 2020.) Greene was “probably the first photographer we know of who was trained archaeologically,” says Frederick Bohrer, an art historian at Hood College in Maryland, and the author of Photography and Archaeology.

In the 19th century, the two disciplines lurched toward a kind of maturity together. Earlier excavations had begun to investigate Stonehenge and other English megaliths, as well as the ash-covered ruins of Pompeii. But for the most part, like the medium of photography, archaeology—at least as it was practiced in Egypt, by Europeans—was an invention of the 1800s. Before that, enthusiasts of history were known as antiquarians, and many were just as invested in sifting through libraries as through dirt.

The switch to the shovels-in-the-ground approach of archaeology happened just before the middle of the 19th century, and by the time Greene first went to Egypt, scientific societies had begun to see photography as a useful research tool for the new field. Drawing, painting, and engraving had worked well enough for the many hundreds of plates and maps in the Description de l’Égypte, the sprawling tome compiled by Napoleon’s brigade of scientists at the end of the 18th century, but the techniques were hugely labor-intensive.

“To copy the millions of hieroglyphics which cover even the exterior of the great monuments of Thebes, Memphis, Karnak, and others would require decades of time and legions of draftsmen,” grumbled mathematician and physicist François Arago, who tried to persuade his peers at the Académie des Sciences that photography was the cataloguing tool of the future. The Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres agreed, Keller writes, and dispatched Du Camp to Egypt, with instructions to “take advantage of every favorable moment” and “to always apply himself, as much as location and time permits, to complete the general views and the details of a monument, whether an entire legend of a complete hieroglyphic tablet.” The idea was to capture everything he could.

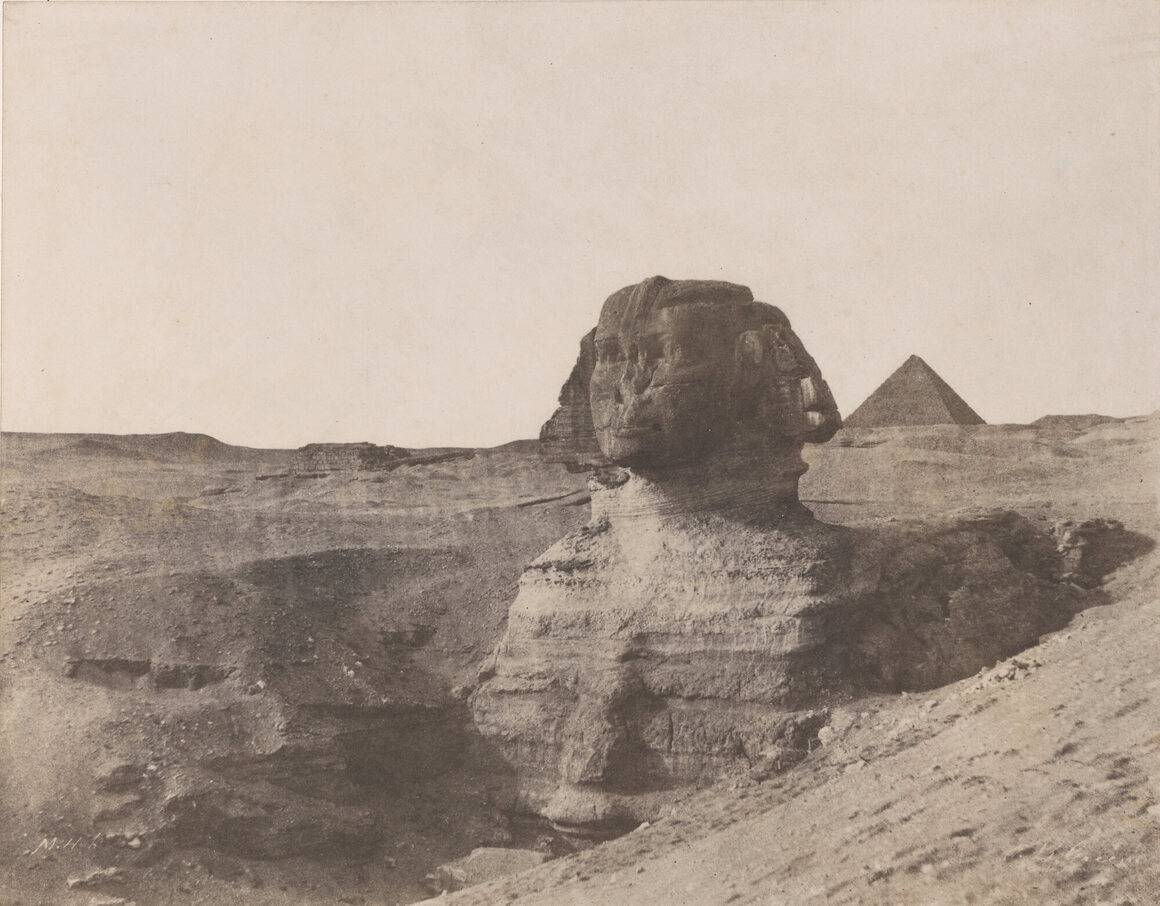

Greene’s approach was rather different. He appears to have been the first science-trained photographer to depict an excavation in progress—his own, at Medinet Habu, plus a dig near Giza—writes archaeologist Michael Press in Hyperallergic. Greene’s photographs are quiet, heavy on ground and sky, and nearly empty of people. Because European excavations in Egypt hadn’t yet reached the frenzied pitch they soon would, many of the structures he photographed were still swallowed by centuries of rubble. one example is the Temple of Dendur—long before it made the journey to America, where it now sits in its own room in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Today, it’s surrounded by soaring glass and a placid pool; in Greene’s photos, it’s strewn with chunks of rock.

It’s not that it was impossible to include people in images. Exposure times could be less than a minute (but were often much longer), meaning that while movement was impossible to capture as anything other than a blurry, ghostly streak, subjects could sit, stand, or sprawl long enough to show up clearly. But even when figures are present in the images, Press points out, Greene’s captions ignore them. An 1854 image featuring a clearly defined, contemporary structure and blurry figure is titled “Etudes de dattiers” (or “Studies of Date Palms”), Press notes, “as if the person and their domicile were invisible or incidental.”

Some contemporary scholars suspect that Greene’s compositions were informed by artistic choice, and the European perspective that sidelined or erased indigenous residents of other countries. His sweeping landscapes borrowed from the atmospheric style of his teacher Gustave Le Gray, who pioneered a technique of waxed paper negatives and salted paper prints, Press writes. But portraying these landscapes as vast and empty also affirmed a colonial agenda, suggesting that that these were places just waiting for Europeans to stroll in and make their mark.

“Photographs like these are engaging with conventions of artistic representation in many areas of the world, and the Middle East in particular, that were being seen as empty spaces ripe for Europeans to go in and give meaning to,” says Christina Riggs, a historian of archaeology, photography, and ancient Egyptian art at Durham University and a fellow at Oxford’s All Souls College. “Colonialism is a crucial factor in considering the circumstances in which such photographs were being made in the first place.” Later photos taken by the English photographer Francis Frith featured many more people, but they were there for scale, as proxies for traveling Europeans or armchair adventurers, or as local representations of the titillating and ‘exotic,’ Keller writes.

As archaeology and photography continued to develop in tandem, Bohrer explains, crews would sometimes literally sweep aside the people who lived in a place before they photographed it. At the Acropolis in Athens, he says, archaeologists removed homes, military barracks, and a mosque before snapping photographs. A site “never looks the way it did when these photographs were taken,” he says.

Greene’s life was short, and details about him are hard to come by. Many of his photographs were exhibited before he died of an illness in Cairo in 1856, at the age of 24, but then his work “languished in almost total obscurity for a hundred years,” Keller writes. It was dusted off in the 1970s and 1980s “as part of a resurgent interest in the medium’s early history.” His images don’t tell any sort of complete story of Egypt, then or now. But they have become artifacts in their own right.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.