Tradition and Invention

The idea that Jews had a tradition of political thought, as well as an active political life that continued in various shapes and forms over the vast expanse of their diaspora existence, is a new one. It is difficult for most people living today to imagine a time when the notion of Jews as a people who had lived without a continuous political life for two thousand years was virtually a matter of common consensus. Christians conceived of Jews as having exhausted their right to a political existence following their rejection of Jesus as their savior. The figure of Synagoga adorning so many medieval cathedrals always appears bereft of her crown and holding a broken staff or lance to symbolize this loss of sovereignty. Jews were entitled to practice their religion but were politically subordinate within the orbit of Islam as well.

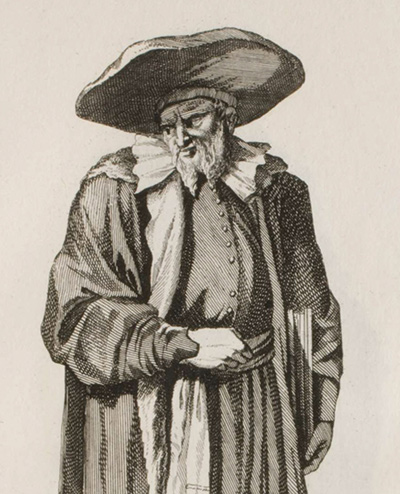

Any overt expressions of political ambition, such as messianic movements, were brutally suppressed. The most notable of these movements was that of Shabbtai Zevi in the 17th century. Whether this upsurge represented the culmination of medieval messianic dreams or the inauguration of a modern revolt against a powerless life in the diaspora is still a matter of scholarly debate. But however one characterizes the Sabbatean movement, it barely altered the perception that Jews were a people without politics.

In the modern era of civic and legal emancipation, the Jews often acquired equal rights as citizens of the nation-state under the explicit condition that they surrender all vestiges of autonomous political life. As the Count of Clermont-Tonnerre famously declared in 1789 during the debate over Jewish citizenship in the French Assembly: “The Jews should be denied everything as a nation, but granted everything as individuals,” a bargain that French Jews tried hard to accept. Nevertheless, antisemitic classics produced in this period, such as Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Jacob Brafman’s Book of the Kahal, depicted a unified Jewish people as politically vibrant, xenophobically separatist, and globally ambitious. These works inverted the picture of political quietism and harmlessness projected by Jewish leaders. Even (or particularly) within the 19th-century movement to develop and promote the academic study of Jewish culture, history, and religion, known in German as Wissenschaft des Judentums, Jewish political life barely registered as a subject. If the term “politics” entered into discussion, it almost always meant the negotiations between Jews and a non-Jewish political entity and only rarely something that Jews practiced themselves.

If Jews were included in early 20th-century discussions of political communities, it was generally concerning their right to preserve their language and culture, along with other minorities, at a time when empires were being dismantled. The neglect of the idea of Jewish political life largely persisted until the rise of Zionism and the subsequent establishment of the State of Israel. In short, the idea that the Jews possessed a distinctive political tradition during the two millennia of diaspora only arose around the emergence of a modern sovereign Jewish state. All of which is to say that The Jewish Political Tradition, a projected four-volume anthology reaching back to the Bible, the Talmud, medieval philosophers, and halakhic authorities and culminating in our own times, the third volume of which has recently appeared, would have been almost inconceivable not long ago.

The project is animated by the presiding intellectual spirit of Michael Walzer, the eminent political theorist and moral philosopher, who has coedited each of the volumes along with the scholars of Jewish thought Menachem Lorberbaum and Noam Zohar. Each volume collects texts around a central theme: the first, authority; the second, membership; and the present volume (for which coeditor Madeline Kochen joined the three founding editors), community.

In his introduction to the first volume, Walzer wrote that “the tradition as a whole is our subject in these volumes” (my emphasis) and described their project as threefold: an act of retrieval, integration, and criticism. That is, it would retrieve “central texts and arguments” of Jewish political thought and make them available to new generations of readers. “Never before,” Walzer wrote, “has the tradition been looked at . . . with our specific set of questions about political agency and authority in mind.” But it would also “take . . . Jewish thought out of its intellectual ghetto,” by integrating it with “Greek, Arabic, Christian, and secularist modes of thought.” Finally, their project would not simply accept the arguments and doctrines of this tradition but rather “argue and . . . encourage others to argue about which of them can usefully be carried forward under the modern conditions of emancipation and sovereignty.”

To that end, each of the volumes seeks to trace the development of Jewish political ideas through a rich range of beautifully translated texts, culled with evident care and discernment. These sources are accompanied by brief reflective essays from leading American and Israeli jurists, philosophers, and political thinkers. Thus, in the new volume on community, Judge Jed Rakoff writes on the courage and responsibilities of judges; the noted Harvard political theorist Michael Sandel discusses the parallels (or lack thereof) between community and nation-state bonds; and Fania Oz-Salzberger contributes a commentary titled “Tzedakah, Zionism, and the Modern Jewish Citizen.”

However, the problem with the project is more fundamental than its gathering of experts in other fields (after all, outsiders sometimes see things that the experts have missed). In his foreword to the first volume, the late David Hartman, founding director of the Shalom Hartman Institute, writes:

Israel’s loss of sovereignty and its exile from the land did not mean the end of this community. Rabbinic Judaism developed a comprehensive way of life mediated by explicit and precise legal norms that sustained the collective thrust of Judaic spirituality. . . . But with the establishment of the state of Israel—the third Jewish commonwealth—Jewish thinkers have to address again the central issues of collective existence.

It is undoubtedly true that the loss of sovereignty did not spell the end of organized community life. As Walzer writes, “[P]olitics is pervasive, with or without state sovereignty.” Rather, the issue is that trying to retrieve models from the past with a decidedly contemporary political purpose makes it difficult to see what those past models were, how to interpret them, and even where to look for them.

The imposing volumes of The Jewish Political Tradition confront the reader with an almost seamless new scripture on Jewish politics. Texts that were originally contingent, dialectical, interpretive, or narrative appear alongside apodictic and authoritative pronouncements, joined together in one comprehensive tradition. Yet such a presentation inevitably violates the true meaning of the texts, which were written in wholly different historical contexts and distinct literary genres. Rather than being presented as part of conversations that took place in response to specific challenges in other times, places, and political configurations, they appear here only as snippets in intertextual dialogue with one another.

Moreover, no attempt is made to differentiate between ideas expressed in biblical and Second Temple texts when Jews had at least some measure of sovereignty and those that developed during a period of extensive communal autonomy within another state such as the geonic period or, finally, those that arose in vulnerable Jewish communities, some of them living on the verge of expulsion. It is hard to see how a usable tradition can be retrieved with such methods. It is here that the perspective of historians could have come in handy, but no historians of the Jewish political experience itself appear in the pages of this volume.

In a project whose stated goal is to provide inspiration and guidelines for a thriving state, the absence of lived historical context is particularly puzzling. The book contains, for instance, no echo of the world documented by the Cairo Geniza, with its multiple competing Jewish communities (rabbinic-Babylonian, rabbinic-Palestinian, and Karaite) and its (sometimes polygamous) family structures, deeply embedded in the caliphal framework. The emphasis on text over experience produces a far more idyllic image of Jewish politics past than history itself actually reflects.

The illusion of continuity of a tradition over time and the presentation of texts without a sense of the historical context in which they were produced (or even the approximate dates when they were written) deprives the reader of insight into one of the most remarkable aspects of exilic Jewish life over the past two millennia: the repeated invention and reinvention of Jewish political life. The Jews who fashioned new organizational structures and new kinds of relationships with governing authorities in Abbasid Babylonia, in Umayyad Spain, and in the newly settled Rhineland communities in the 10th century inherited no usable template from antiquity. The achievement of the Babylonianexilarchs and geonim and of Rabbeinu Gershom and his contemporaries and successors was a grand rethinking of what it would take to establish Jewish collective life in new and unfamiliar circumstances. In each case, there was a complete reconception of the very basis of power, polity, community, and kinship in Jewish life.

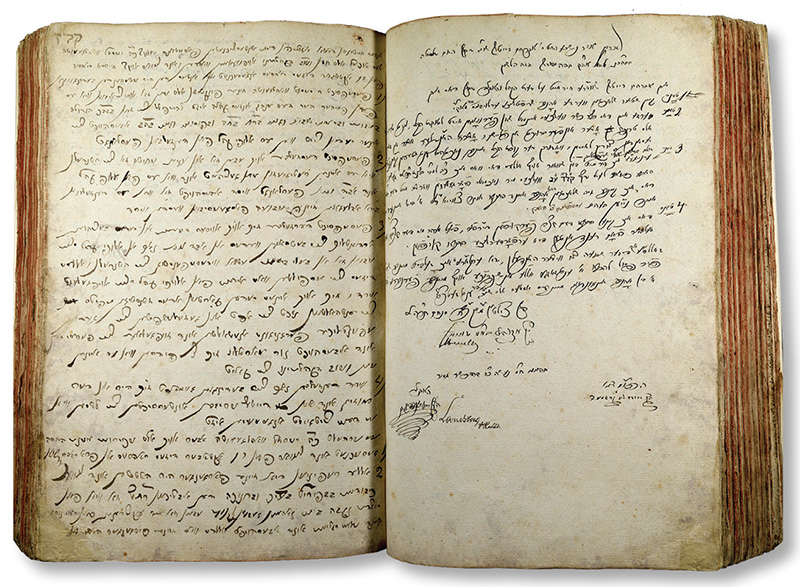

The introduction to this third volume describes the kahal, which was the elected governing body over the Jewish community (kehilla), as its embodiment. It speaks of “the days of the kahal” as a discrete period, yet with a few exceptions, this volume scants the period of greatest actualization of the power of the kahal. Jews of the early modern period who resettled in Europe have left us a veritable treasure trove, thousands of records of their bylaws and institutions, a literature collectively dubbed pinkasim that has just begun to draw the scholarly attention it deserves. This profusion of regulations and documents from the 16th through the 18th centuries, which parallels the growth of bureaucratic culture in Europe, provides the clearest picture of the actual workings of Jewish political life as opposed to its idealized representation. It receives very short shrift in The Jewish Political Tradition, whose editors thus missed an opportunity. They explain this omission on the grounds that “most of the texts come from rabbis.” While this is true regarding contested matters that required halakhic decisions, the majority of texts issuing from a kahal were written by scribes at the behest of lay leaders. Voluntary societies, chevrot, we are told, were “governed by a book of rules drawn up . . . by the founders—a kind of constitution (which the kahal never had).” But many kehillot, such as Krakow, for example, did draw up founding documents, takkanot, with preambles and governing principles that resemble constitutions in this period.

Such blind spots lead to significant errors of generalization. Thus, the third volume’s introduction claims that “the family generally is shielded from communal interference and regulation.” In fact, documents from the archives of hundreds of kehillot demonstrate the opposite. No marriage could proceed, no family could be formed, without the consent of the kahal. It extended its protection to certain families but not to others, and acted in the place of families when they could not care for their dependents.

The absence of kehilla-generated material is particularly glaring in the final chapter of the book, devoted to “the courts.” We now know a great deal about the procedures of Jewish courts in early modern Europe, the ways they adapted to the broader legal environment, and how they dispensed justice, but no hint of what Simha Assaf described decades ago or what Jay Berkovitz and Edward Fram have written more recently intrudes here. Drawing a direct line from antiquity to the 20th century without elucidating the shifting contextual frameworks ignores the genius and persistent innovation of Jewish community life when it arguably reached its apogee in “the days of the kahal.”

Instead of instances of kahal governance and legislation, we get an encomium to the Council of Four Lands (Va’ad Arba Aratzot) that misunderstands its function and role. The councils instituted by the Polish government in the 16th century to collect taxes more efficiently from Jews ultimately served other purposes as representatives and intercessors for Jews. They had no real authority over Jewish communities, and their resolutions were not binding. None of the councils ever presented themselves, nor were they ever conceived in their own time as a representative body of all Polish Jews. When they address questions of “percentage of suffrage”—how many Jews participated in the vote or its decision procedures—the editors demonstrate that they subscribe to an even more idealized picture of the council than the 17th-century chronicler Nathan ben Moses Hannover, who is criticized by the editors for romanticizing the institution. The moment the Polish government decided to disband the council, it disappeared. No effort was made by Jews to continue its other functions privately.

The retrojection of notions of “suffrage” into the discussion of the Council of Four Lands exemplifies the teleological cast of the entire project. An underarticulated argument inspires the compendium: From its inception as theocracy, Jewish political life has always been advancing toward democracy. The idea of a continuous political arc diminishes the value we can attribute to the creation of new forms of Jewish political organization, from the exilarchate and kahal councils to what historian Yosef Yerushalmi has called “Israel, the unexpected state.”

Despite often extremely harsh conditions, ranging from outright physical violence to existential negation of all their claims to a place in history, Jews fashioned means to persevere, to organize social structures, to elaborate their traditions, and even to create monumental works of jurisprudence, liturgy, art, and philosophy. The materials in these volumes have to be understood as much more than the unwitting foundations for a modern Jewish state. They are—despite having emerged mainly outside the context of a state, or perhaps because of it—independent achievements that stand as remarkable in their own right and in the absence of any subsequent vindication by the Jews’ ultimate acquisition of a more conventional sort of political power. Sit in on a meeting of the board of any Jewish organization or watch the Knesset Channel for an hour, and you will find ample confirmation that Jewish politics—voluntary and local or governmental and national—is messy. This is not necessarily a bad thing. It is, in fact, the hallmark of democracies and a point of pride for many Jews. (Amy Gutmann’s essay in this volume, “Meaning and Value of Deliberation,” provides an eloquent reminder of why this must be so.) The decorous tone of the sources and essays that have appeared in the first three volumes of The Jewish Political Tradition dulls some of this vibrancy. Reading them, one can forget about the unexpected twists and turns of history and the spirited inventiveness at the heart of Jewish political life. It might have been different if a historian or two had been invited to participate in the project.