He who is afraid of his own memories is cowardly, really cowardly.

The Remembered Past

On the beginnings of our stories—and the history of who owns them.

By Lewis H. Lapham

Hot Springs of the Yellowstone, by Thomas Moran, 1872. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Beverly and Herbert M. Gelfand.

What, generally speaking, is history? A fable agreed upon.

—Napoleon Bonaparte

Who controls the past...controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.

—George Orwell

A person without a memory is either a child or an amnesiac. A country without a memory is neither a child or an amnesiac, but neither is it a country.

—Mary Astor

Donald J. Trump was elected president of the United States on November 8, 2016. In the three years since, on all platforms of the news and social media, voices choked with anecdote and rage have been asking themselves—and their Twitter followers, the bus driver, Jimmy Kimmel, and the dog—what kind of country are we living in? No news cycle rests content until it calls upon America to remember who and what it is, to get back on the horse of its fabled history.

The commandment strikes a noble pose to camera, but how is it to be carried out? America is a country without a nationalist fatherland like the ones belonging to Germany and France; Americans aren’t bound one to another in blood and soil. The Declaration of Independence endows them with a fable not meant to be agreed upon. In place of a country, we possess the inalienable right to bet our lives and liberties on the reach of our free and equal imaginations. The result is not one history but, as with Walt Whitman, a multitude of histories, and in the autumn of 2019, no small number of them embedded in the memories of politicians and broadcast booths arguing for and against the impeachment of President Trump, accusing one another of trampling out the vintage where the grapes of truth are stored, seeing everywhere on the horizon fact-free dictators slouching toward Facebook to be born.

The spectacle makes a woeful noise unto the Lord, but it provides occasion to ask in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly: What is memory and where is history? The questions have been shaping the hyperpolarized forms of American identity politics for the past thirty years, demanding removal of statues from public parks, freedom of speech from private schools, drumming up the sound and fury of the country’s culture wars, dividing we the people into militant factions of us and them.

The discord follows from the absence of a fable agreed upon, the asset listed in Plato’s Republic as the “noble falsehood” that binds society together in the swaddling cloth of self-preserving myth. Socrates teaches the lesson to a young Athenian aristocrat in the fourth century bc—the children of the city must be told that the god who made all of them mixed some of them with gold, thereby equipping a precious few to rule the city “because they are the most valuable.” Whether the intel is true or false, fake news or the solid nonpareil, matters less than the children remembering their duty to believe it, to know what their rulers would have them know in order to maintain the health and well-being of the body politic.

But not the health and well-being of the individual required to give up an owner’s interest in his or her own mind. Which is the lesson taught by George Orwell in the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four to the democrat Winston Smith, who realizes that if the ruling party of Big Brother “could thrust its hand into the past and say of this or that event, it never happened—that, surely, was more terrifying than mere torture and death.”

Orwell’s novel argues that control of the past is best left to the individual, because memory is the making of ourselves as once and future human beings. We have no other star to steer by, no other ship in which to sail. The mythology of the ancient Greeks marries Mnemosyne, goddess of memory, to Zeus in his persona as the force of nature; the nine Muses born of their union, among them those of history and astronomy, bestow the arts with which humankind discovers who and what and where it is. Saint Augustine, fourth-century Christian bishop in North Africa, says of memory that “it is awe-inspiring in its profound, incalculable complexity. Yet it is my mind: it is my self. What, then, am I, my God? What is my nature?”

The nineteenth-century British novelist Samuel Butler locates memory in the bottomless well of consciousness at the center of every human universe.

To live is to continue thinking and to remember having done so…Thought, in fact, and memory seem inseparable; no thought, no memory; and no memory, no thought. And as conscious thought and conscious memory are functions one of another, so also are unconscious thought and unconscious memory. Memory is, as it were, the body of thought, and it is through memory that body and mind are linked together.

Memory is also the link that contradicts the dictum of the eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon, author of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, who rates history as “little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind.” He refers to the recorded past, the one carved in stone, stored in libraries, given up for dead. History is better understood as the remembered past, the one recognized by Augustine as “the great force of life in living man,” identified by the historian Margaret MacMillan as “that imaginary place, ‘the real world.’ ” The recorded past is a spiked cannon. The remembered past is live ammunition—not what happened two hundred or two thousand years ago, a story about what happened two hundred or two thousand years ago. The stories change with circumstance and the sight lines available to tellers of the tale. Every generation rearranges the furniture of the past to suit the comfort and convenience of its anxious present. Michel de Montaigne in one of his essays provides, as is his custom, an apt quotation:

See how Plato is moved and tossed about. Every man, glorying in applying him to himself, sets him on the side he wants. They trot him out and insert him into all the new opinions that the world accepts.

To read three histories of America’s founding, one of them composed in the nineteenth century, the others in the twentieth and twenty-first, is to travel in time to three castles in air. The must-see tourist attractions remain securely in place—Jefferson drafting the Declaration of Independence, Washington crossing the Delaware, Hamilton organizing a national bank—but as to the light in which events are to be seen, accounts differ. The histories are posed in sculptured marble or framed in Hollywood tinsel, but in no instance is the immortal American past the product or property of a country. Countries are figurative entities on the field of a flag; they don’t own things. The immortal American past belongs to the people who carry it around in their heads. The Pennsylvania countryside blossoms every summer with the appearance of ten thousand volunteers in Civil War uniforms to revive the Battle of Gettysburg.

Francesco d'Este, by Rogier van der Weyden, 1460. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931.

So vivid in the popular imagination is the iconography of the American past that it’s no surprise when in the course of reviewing the day’s news, somebody at the kitchen table or the hotel bar wonders what John Adams would have said about the pornographic film industry, how John Wayne would handle the Mexicans crossing the Rio Grande. Why candidates for political office promise to take America back but don’t take follow-up questions. Back where and from whom? By what means of conveyance? In a covered wagon or aboard a corporate jet? If back home on the range, do the deer and the antelope still play with Kevin Costner and the Teton Sioux? If from the grasp of venal politicians and vampire capitalists, does Susan B. Anthony go to the White House and John D. Rockefeller to prison? If a happy return to the American Garden of Eden, who among the founders deserves credit for design of the landscape—the Jefferson who planted the seeds of liberty or the Jefferson who used slaves to work the plantation?

The Constitution makes no claim to the possession of a storied past. The institutions of American government were meant to support the liberties of the people, not the ambitions of the state. Given any ambiguity on the point, it is the law that gives way to the citizen’s freedom of thought and action, not the citizen’s freedom of thought and action that gives way to the law. The Bill of Rights establishes the order of priority in the two final amendments, the Ninth (“The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people”) and the Tenth (“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states, respectively, or to the people”). Even so faithful a servant of the moneyed interests as Daniel Webster understood the message—“The public happiness is to be the aggregate of the happiness of individuals. Our system begins with the individual man.” Construed as means instead of end, the Constitution stands as preamble to a narrative rather than plan for a monument. Individual narratives running on memory and making themselves up as they roll merrily or not so merrily along.

But where do the stories begin, how far back in the reaches of time? Socrates in the Phaedo says that memory is bestowed on us before birth, that all knowledge (historical and ahistorical, public and private, conscious and unconscious) is prior knowledge: “If anyone recollects anything, he must have known it before…as long as the sight of one thing makes you think of another, whether it be similar or dissimilar, this must of necessity be recollection.” The newborn infant comes into the world full-blown from the head of Zeus, reliably informed about “all those things which we mark with the seal of ‘what it is.’ ”

Our twenty-first-century psychologists suggest that the whereabouts of memory is no longer a question of metaphysical speculation. According to the essayist

So, too, I’m bewildered by wonders that never cease and unable to look a gift horse in the mouth. I have no evidence with which to challenge the wisdom of Saint Augustine and Plato, or to quarrel with Mark Twain’s 1903 advisory to Helen Keller:

As if there was much of anything in any human utterance, oral or written, except plagiarism! The kernel, the soul—let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances—is plagiarism. For substantially all ideas are secondhand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources…not a rag of originality about them anywhere except the little discoloration…revealed in characteristics of phrasing.

About my own memory, all I can say for certain is that it’s an equal-opportunity employer, a work in progress, and a democratic society open to millions of secondhand ideas interleaved with more millions of firsthand fears, instincts, and emotions. To the best of my knowledge and recollection, I’ve never had an original thought. Fortunately, I was endowed by the creator with a love of reading.

So was

Someone will remember us

I say

even in another time.

The pamphlet is the founding document of the American Revolution. Paine levels a fierce polemic against “the disease of monarchy,” asks why should someone rule over us simply because he is someone else’s child. Common Sense forces the point that all men deserve free and equal ownership of their own minds. Their memories are not the property of Big Brother King George III. The time was at hand to do away with hereditary succession, class privilege, and titled aristocracy. It was, he said, “the birthday of a new world.”

Paine’s words were received with hats-in-the-air excitement everywhere in the colonies. The pamphlet sold 150,000 copies in six months, an enormous circulation for the day and age. It was proof of an emerging national resolve that emboldened Thomas Jefferson to borrow Paine’s notion of all men being created equal when he came to the writing of the Declaration in June 1776.

The revolution was fought with words as well as muskets, none more effective than Paine’s Crisis papers, begun while he was serving in the ranks of Washington’s dispirited army, retreating south through New Jersey in the autumn of 1776 from its lost battles in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Washington ordered the reading of the most famous Crisis paper—“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman”—to volunteer militia on the night of their crossing the Delaware River to mount a surprise attack on British and Hessian troops celebrating Christmas Eve in Trenton. Washington credited the victory to Paine’s inspired rhetoric. Years later he went on to say that if his army had not won the fight at Trenton, America would have lost the Revolutionary War.

All the founders of the American republic were devoted students of history and readers of books. Madison and Adams framed their envisioning of just government on the works of Cicero, Polybius, and Plutarch as well as on those of Montesquieu, Hobbes, and Locke. They drew heavily on the live ammunition that is the past living in the present and the present living in the past.

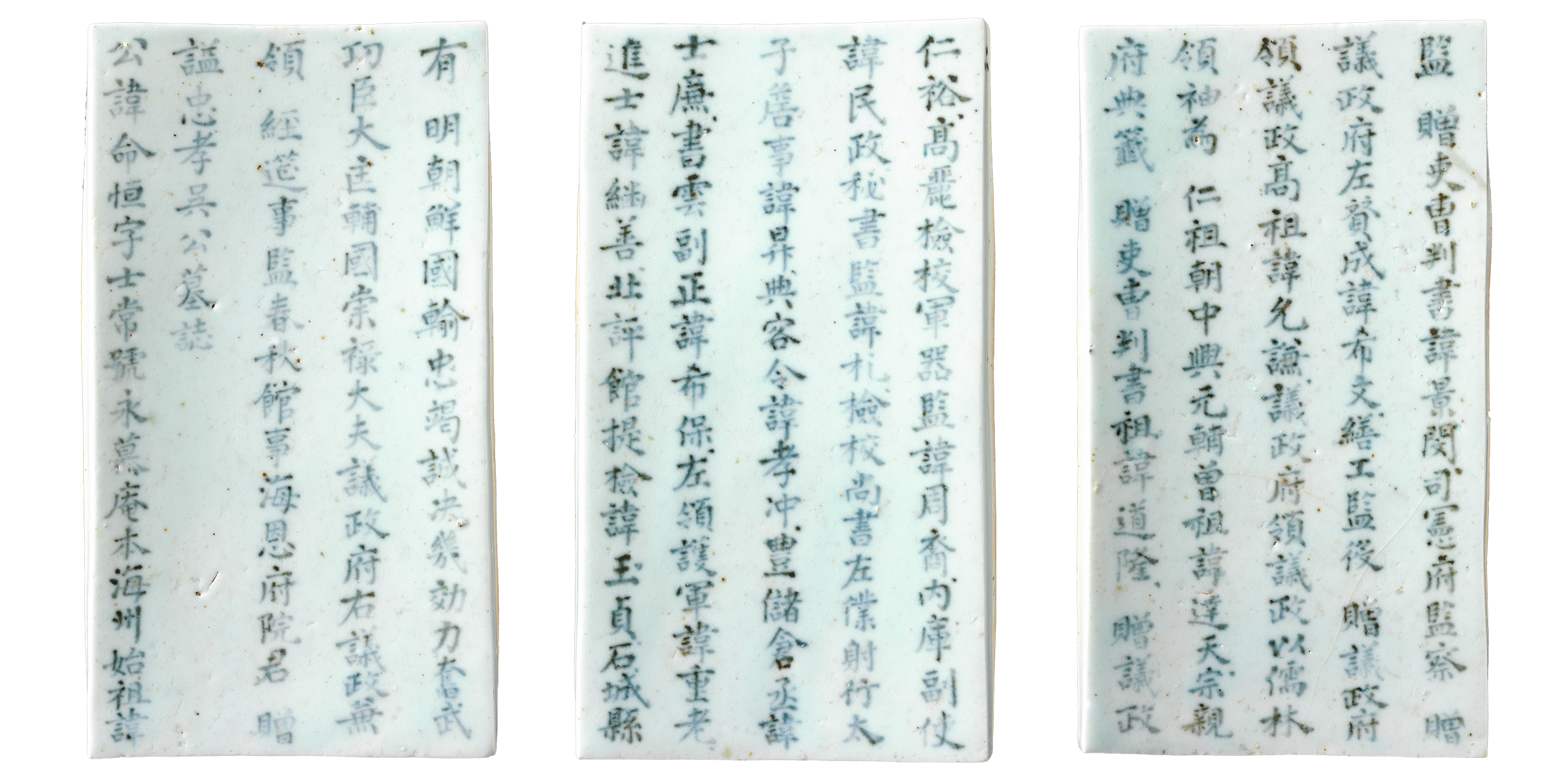

Myoji (epitaph tablets) commemorating the life of the calligrapher and statesman O Myeong-hang, Korea, 1736. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of The Honorable Joseph P. Carroll and Mrs. Carroll, to commemorate the opening of the Arts of Korea Gallery, 1998.

To read Paine is to encounter the elevated thought of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment rendered in language easily understood by everybody in the room. Madison and Adams addressed the well-educated members of their own privileged class. Paine talks to ship chandlers and master mechanics and tavern keepers, to wives, widows, and orphans. In place of a learned treatise, he substitutes the telling phrase and the memorable aphorism.

Once America won the war for independence, Paine found his particular talents no longer called for, and in 1787 he sailed to Europe, still bent on political transformation and social change. In England he wrote Rights of Man, the book in which he sought to give programmatic form to a just society and which, 150 years ahead of its time, anticipates much of the legislation that eventually shows up in the United States under the rubric of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal—government welfare payments to the poor, pensions for the elderly, public funding of education, reductions of military spending, an estate tax limiting the amount of an inheritance. The book appeared in two volumes, in 1791–92, instantly and immensely popular with the reading public not only in England but also in France. The sale of 500,000 copies ranked it as the best-selling book of the entire eighteenth century and prompted the British government to charge its author with treason and declare him an outlaw.

When Paine crossed the Channel to Calais in the summer of 1792, a rejoicing crowd of newly enfranchised citizens accorded him a hero’s welcome. To the makers of the French Revolution, Rights of Man bore the stamp of divine revelation, and as testimony of their appreciation, they promptly elected Paine to the political assembly then at work in Paris on the construction of another new republic.

The abundance of Paine’s writings flows from the spring of his optimism, and during the twenty years of his engagement in both the American and French revolutions, he counts himself a “friend of [the world’s] happiness.” No matter what question he takes up (the predicament of women, the practice of slavery, the organization of government), he approaches it with generous impulse and benevolent purpose, invariably in favor of a new beginning and a better deal.

When it shall be said in any country in the world, my poor are happy; neither ignorance nor distress is to be found among them; my jails are empty of prisoners, my streets of beggars; the aged are not in want, the taxes are not oppressive…when these things can be said, then may that country boast its constitution and its government.

The democratic idea is not a fable crowned in marble or a tip on a dead horse. It is work in progress, the shaping and reshaping of a once upon a time that proceeds on the assumption that nothing is final; like memory, the democratic idea is the discovery and rediscovery of what it means to be a human being. Roosevelt voiced Paine’s thought in a radio broadcast in the autumn of 1938, talking to the American people about the reactionary Wall Street interests seeking to break down the structures of the New Deal:

I venture the challenging statement that if American democracy ceases to move forward as a living force, seeking day and night by peaceful means to better the lot of our citizens, then Fascism and Communism, aided, unconsciously perhaps, by old-line Tory republicanism, will grow in strength in our land.

American democracy ceased to move forward as a living force in the 1980s. Given the impetus of what was billed as the Reagan Revolution, old-line Tory republicanism has grown into the petrified forest of a selfish and frightened plutocracy distilled in the essence of Donald J. Trump. We live in the spirit of an age convinced that money is the hero with a thousand faces, technology the salvation of the human race.

Increasingly over the past forty years, we have learned to live in a world in which it is the thing that thinks and the man who is reduced to a thing. In place of memory, we have machines to tell us who and how and what we are, where to go and what to do, text A for yes, B for no. Not only do we not object to our dehumanization, we regard it as a consummation devoutly to be wished—to be minted into the coin of celebrity, become a corporation, a best-selling logo or brand, an immortal product in place of mortal flesh.

Our remembered past becomes the property of Big Brother Facebook, heir to the throne of Big Brother King George III. The company’s market capitalization of $550 billion accrues from the sale and resale of other people’s memories—their lives and liberties and pursuits of happiness included in the low, low bargain price for their likes and dislikes. Facebook algorithms some years ago started cheerfully suggesting to survivors of terrorist attacks happy reminiscences of the tragedies. Embarrassed by its stupidity, Facebook in 2018 proudly introduced a new algorithm designed to detect and suppress undesirable memories.

There’s hope a great man’s memory may outlive his life half a year.

—William Shakespeare, 1600America’s democratic republic is founded on the meaning and value of words. Silicon Valley’s data-mining engineers have no use for the meaning and value of words; their machines process words as lifeless objects, not as living subjects. Not knowing what the words mean, the technology neither knows nor cares to know who or what or where is the human race, why or if it is something to be deleted, edited, or saved.

The expanding reach of the internet broadens the market for “innovative delivery strategies,” brightens our horizons “with quicker access to valued customers.” But the incessant bombardment of new and newer news blows away the chance of knowing what most or any of it means, and darkens the approach to the value of our minds. The sound and fury of an instantly shattering Now carries away all thought of what happened yesterday, last week, two hundred or two thousand years ago. Not only do we lose track of our own stories, we forget that the stories in the old books are also our own. Cicero made the point fifty years before the birth of Christ—“Not to know what happened before one was born is always to be a child.”

Paine took the advisory to heart, characterizing his own writing as “the undisguised language of historical truth.” The problems that engaged his reading and writing in the late eighteenth century are the ones we know today under the headings of income, racial, and gender inequality, class conflict, the war between rich and poor. The Trump government currently occupying Washington Paine would have recognized as “royalist” in sentiment, “monarchical” in its mistrust of freedom, “evangelical” in its worship of property. The voice of Thomas Paine speaking to his hope for the rescue of mankind is, by comparison with the sound bites now littering the floors of Congress and the White House, the sound of water in a desert.