Credit: Sotheby's

To an untrained eye, the "Mona Lisa" up for auction at Sotheby's next week is indistinguishable from its namesake hanging in the Louvre.

The columns painted either side of the canvas are just a small giveaway that this isn't Leonardo da Vinci's original. But there is another, more noticeable difference: the price tag.

Produced during the 1600s, perhaps more than a century after Leonardo's death, this "Mona Lisa" is expected to sell for $60,000 to $80,000. And in a highly unusual move, Sotheby's has included a batch of six other copies in Thursday's sale.

Among them are reproductions of other iconic artworks, including Caravaggio's "Medusa" and Hieronymus Bosch's triptych "The Garden of Earthly Delights." Versions of works by other Old Masters -- the greats of pre-19th-century European art -- such as Diego Velázquez and Correggio will also go under the hammer.

A 19th-century copy of Diego Velázquez's "Triumph of Bacchus" has a low estimate of just $10,000 at Thursday's sale. Credit: Sotheby's

Copies may be associated with art-world fraud, but there are many legitimate reasons why they were made, according to Christopher Apostle, senior vice president and head of Old Masters at Sotheby's.

"Historically speaking, a copy wasn't necessarily viewed as negatively as it might have been later," he said on the phone from New York, where the sale is taking place. "We know that collectors of famous paintings hired specific artists to create copies that they could give away or hang in other residences."

As late as the 20th century, reproducing Renaissance or Baroque masterpieces was also a common part of formal artistic training, helping students to perfect their color, shading and composition, Apostle said. Some replicas were even produced by the original artists' own students. Proteges and trainees were often permitted to copy their masters' work, although only once they had acquired the requisite skill to do them justice.

A 19th- or 20th-century copy of Hieronymus Bosch's triptych "The Garden of Earthly Delights." Credit: Sotheby's

"Very often, a copy was the only way that an artist could disseminate a famous or successful composition," Apostle said. "The artists themselves might run a workshop, if they thought 'wow, I really hit a home run with this particular composition,' and their pupils would then make replicas."

The seven paintings going under the hammer Thursday are all what Apostle calls "honest copies" (according to the auction catalog, such artworks were "rarely intended to deceive potential buyers"). But their stories, and proximity to the originals, differ greatly.

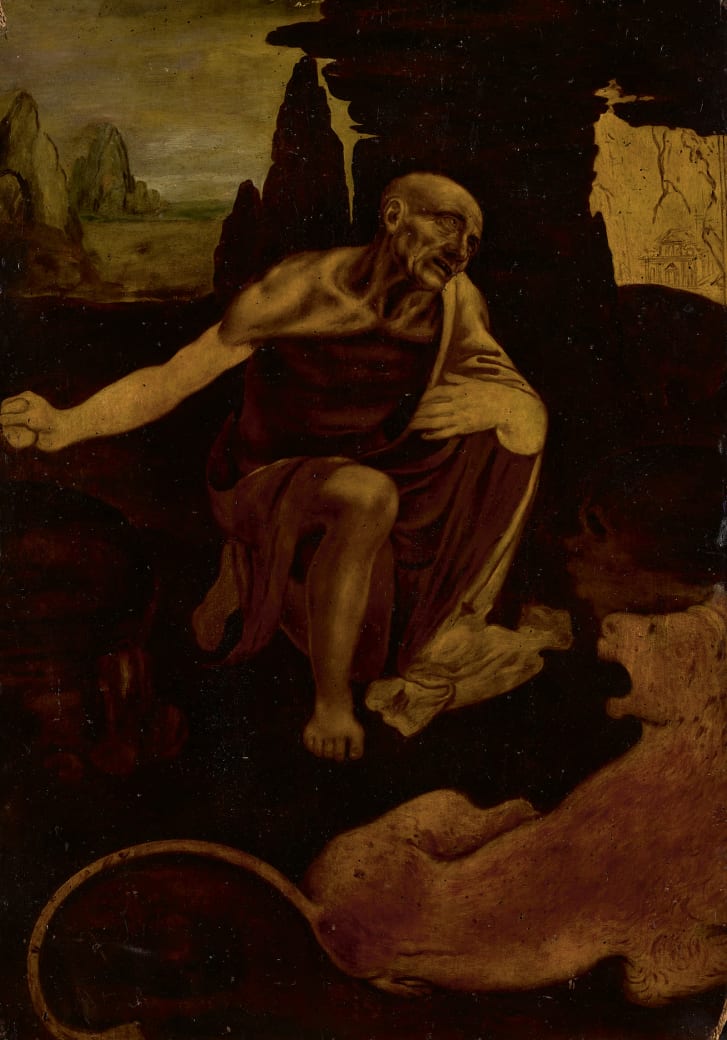

Most were painted after the original artists' lifetimes -- though in the case of another Leonardo copy on sale, "Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness," only by a few decades. The aforementioned Bosch triptych, meanwhile, could have been painted as recently as the 20th century.

But the oldest of the works being auctioned, a copy of Michael Sweerts' "Plague in an Ancient City," is attributed to someone in the Flemish painter's direct circle, though little is known about the copyist.

A copy of Michael Sweerts' "Plague in an Ancient City" is attributed to someone in the painter's immediate circle. Credit: Sotheby's

Although far cheaper than originals, copies can still attract significant sums on the art market. Just last year, Sotheby's oversaw the sale of a different "Mona Lisa" for almost $1.7 million, which the auctioneer believes to be a record for a copy.

Nonetheless, Sotheby's is hoping the relatively low prices will appeal to a new type of collector. Apostle said that copies can serve as an affordable way into the often-extortionate world of Old Masters. A 19th-century copy of Velázquez's "Triumph of Bacchus," for instance, has a low estimate of just $10,000 going into Thursday's sale.

"As our market becomes more global, and we get more buyers from places like Asia and other emerging markets, I think a copy is a very acceptable starting point," Apostle said. "They can buy their Leonardo or their Caravaggio at a price-point that is not reflective of an original."

Sotheby's believes this to be the only known to-scale replica of Leonardo da Vinci's "Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness." Credit: Sotheby's

As for whether they might constitute a sound investment, UK-based art adviser Tim Warner-Johnson recommended distinguishing between copies of "truly iconic" paintings, such as the "Mona Lisa," and lesser-known images.

Why is art so expensive?

But Warner-Johnson, who worked at Christie's before setting up his own art advisory firm, warned that the auction might attract unexpected buyers, which could inflate prices. Rather than adding to their Old Master collections or investment portfolios, prospective buyers may be acquiring the works for personal reasons, he suggested.

"You would probably be bidding against someone who is making a one-off purchase and is not thinking in terms of investment," he explained. "So they would probably outbid you at auction.

"If I had a client who collected works by Leonardo's pupils, I might consider recommending a good copy of a Leonardo to fit into that collection. But for a 'Mona Lisa' you're probably going to be competing with people who will spend far more than you would advise someone to spend -- people who just want an iconic image."

A copy of Caravaggio's "Medusa" has an auction estimate of $70,000 to $90,000. Credit: Sotheby's

Apostle, though not an owner himself, can attest to the appeal of having an Old Masters on the wall -- he has been keeping the copy of Caravaggio's tortured "Medusa" in his office at Sotheby's in the weeks leading up to the auction.

"I've hung it there because I want to scare people out," he joked. "It's a great image. They can be great fun. I think today they are -- just as they were in the 16th and 17th centuries for the original owners -- signifiers of a kind of culture and love for the artists.