Pause and Effect

The past and future of punctuation marks

Detail from the cover of Le Mot, 1 May 1915, illustration by Paul Iribe. Photo © Bridgeman Images

Detail from the cover of Le Mot, 1 May 1915, illustration by Paul Iribe. Photo © Bridgeman Images

We send each other millions of faces each day, hoping to press complex emotional tones into waywardly arranged punctuation marks: a colon, a dash, half a bracket, closed if happy, open if sad. This seems like a radical reinvention of these marks, yet the real leap of thought happened much earlier.

In classical times there were no punctuation marks or spaces between words. Since punctuation determines sense (‘Let’s eat, Grandpa’ versus ‘Let’s eat Grandpa’), scriptio continua allowed scribes to offer their masters a clean text, waiting to be interpreted by those higher up the social ladder. Writing was merely a recording of, or preparation for, speech: any punctuation that was inserted had oratorical, rather than grammatical, functions, indicating the degree of pauses upon delivery only. There was no such thing as reading at first sight.

During late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages, classical texts were under threat as fewer and fewer knew how to punctuate them. Faced with a potential loss of meaning, scribes and scholars introduced a system of marking pauses, which included a pause between elements of a single sentence whose sense is not complete (which would become a comma), a pause between elements whose sense is complete yet their sentence is not (the future colon) and a pause between two sentences (the full stop). These pauses were marked with dots, respectively low on the line, in the middle and suspended at the top. In the seventh century, Isidore of Seville wrote about the systematisation of punctuation, suggesting a move towards grammatical punctuation, or at least a thorough conflation of grammar and oratory.

Over the following centuries, the existing punctuation marks became increasingly differentiated in order to prevent confusion. At the same time, new marks such as the question mark were born, evidencing a need for further distinction of written language. The 15th century saw a boom of inventive punctuation, including the exclamation mark, the semicolon and brackets (or parentheses). New marks arise when a lack of clarity needs to be redressed, communication controlled and sense disambiguated, an emergency perhaps stemming from greater reliance on written diplomacy as well as the newly fashionable art of letter writing. Brackets, for example, first appeared in the 1399 manuscript De nobilitate legum by the Italian humanist Colluccio Salutati. Salutati’s own additions of the marks around certain sentence elements are visible between the text noted down by his secretary.

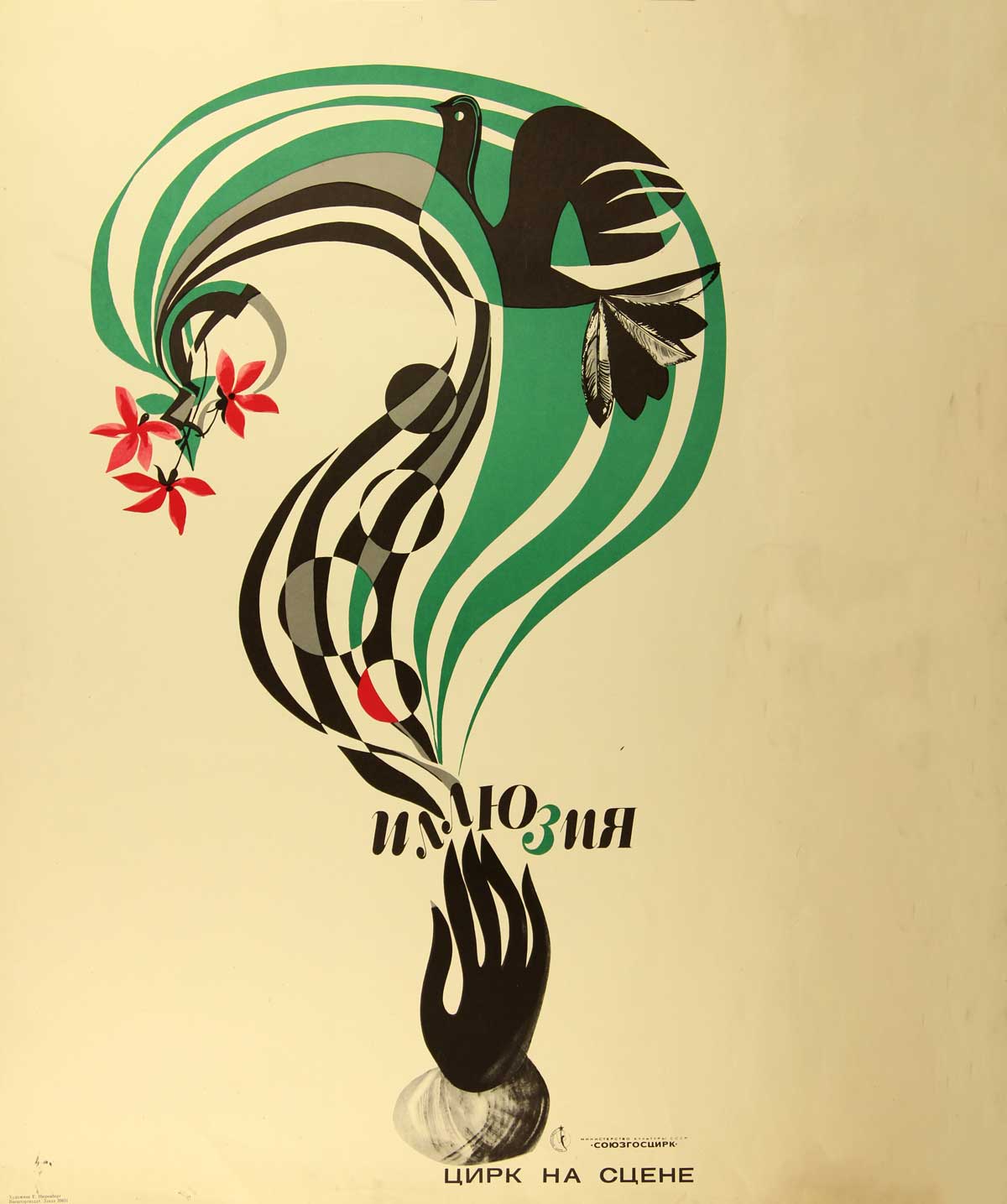

Poster by Elena Krylova-Nurenberg, 1972 © Elena Krylova-Nurenberg, 1972/Bridgeman Images.

Poster by Elena Krylova-Nurenberg, 1972 © Elena Krylova-Nurenberg, 1972/Bridgeman Images.

Such an act of deliberate invention and intervention was imitated around a century later by the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius, who created the hybrid semicolon in Pietro Bembo’s account of his climb of Mount Etna, printed in 1494. Both marks encourage pausing in new ways: brackets introduce (seemingly) external matter into sentences and sense, signalled by their porous typographical walls. How do the eyes – and the mind – move when encountering a bracket? The eye may linger, enter the bracket, at its end circle back to the beginning of the sentence, then jump over those already-read words to the other side of the parenthesis and continue the rest of the sentence. Or we may re-read the entire sentence without leaping around. Or read right through the bracket in the first place, only just registering that there has been a disturbance. Yet a disturbance there has been: the eye and the mind have paused. We have had time for reconsideration of what we read. The semicolon also trades with pauses, although in a more linear fashion; a semicolon lets you go on forever; sentences may be finished or not; you can just let your thoughts flow; and so on.

The printing press allowed the standardisation and rapid spread not only of language and its looks, but also of marks of punctuation. Enthusiastically taken up by humanists and authors across Europe, the correct use of punctuation marks became an intrinsic part of good education and breeding. Yet their ambivalent nature, halfway between speech and writing, continues to reverberate: the 16th-century English educator Richard Mulcaster called brackets, for instance, ‘creatures to the pen, and distinctions to pronounce by’. Their indeterminacy, perhaps, makes theorists of rhetoric and grammar nervous: they prescribed the use of certain punctuation marks as both elegant and reprehensible, something to do by all means – and not do under any circumstances.

By the 18th century, English punctuation trod on the spot, having embraced other early modern inventions such as the dash and ellipses, permitting yet more refined ways of interrupting, hesitating and changing of thought. By the 20th century, punctuation had, again, regained its strong connection to speech, although it did not denote an actual guide to performance, but rather imitated how the voice might look on the page. It also came to inspire modernist writers in their exploration of the human mind and the strange ways consciousness moves. At one end stands Ernest Hemingway, whose numerous full stops cut his prose into repressed chiselled parcels of supposedly objective observations; on the other, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, manipulating the lack of punctuation as a representation of the vagaries of thought. one look at the end of Ulysses suffices to see how Joyce imitates the breathlessness of Molly Bloom’s thought pouring out in masturbation-orgasm as she yes comes on unpunctuated strings yes of words ending yes on yes

The latest major invention dates back to the 1960s, when journalist-turned-advertisement agent Martin Speckter felt only a new sign could express the force of rhetorical questions he needed for his job. The interrobang was born, a monster made by superimposing an exclamation and a question mark. Why on earth did it not catch on? !

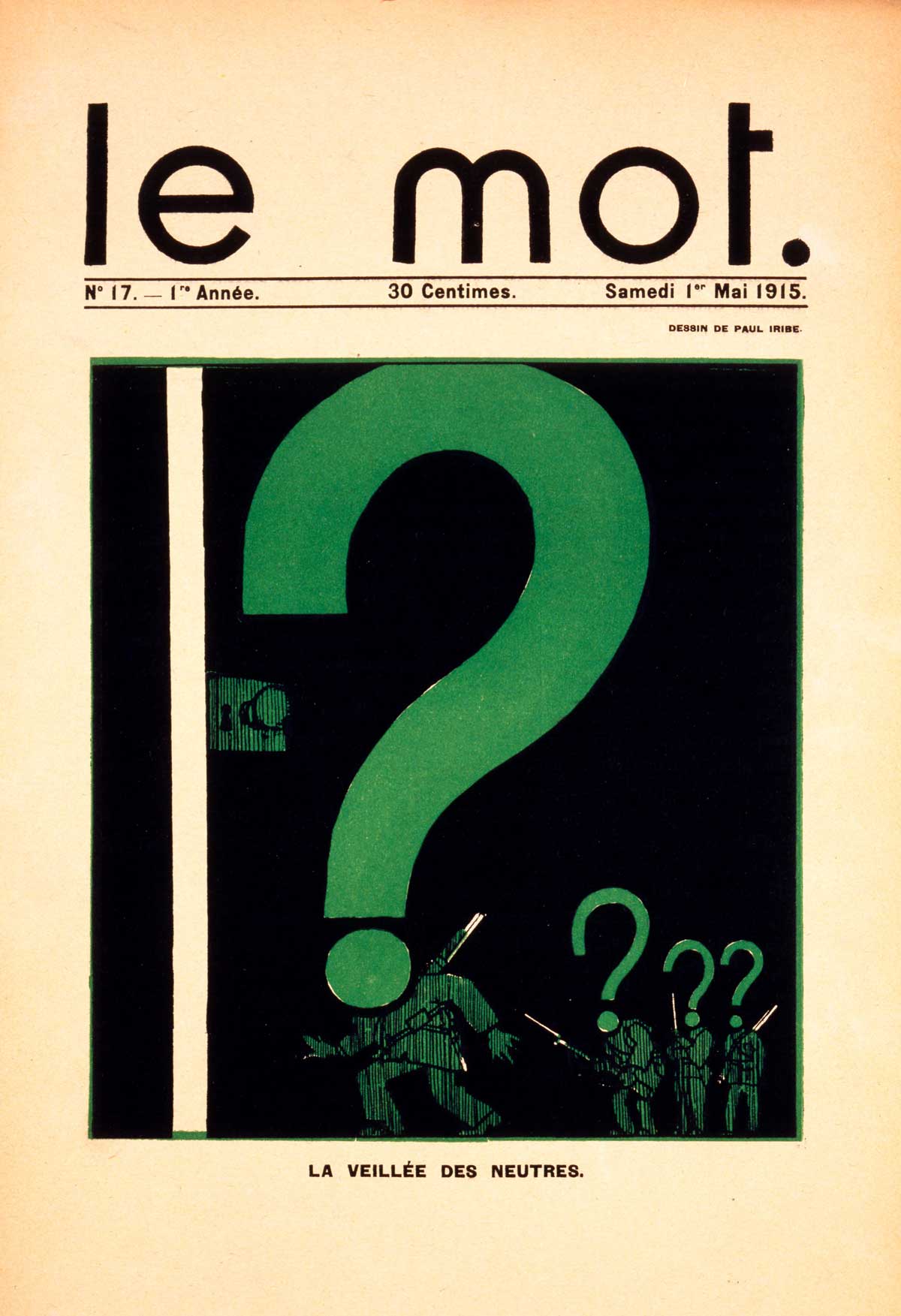

Cover of Le Mot, 1 May 1915, illustration by Paul Iribe. Photo © Bridgeman Images

Cover of Le Mot, 1 May 1915, illustration by Paul Iribe. Photo © Bridgeman Images

What the interrobang does show, however, is that our prime concern today crowds around the absence of tone in writing. In speech, a gesture or facial expression upend the emotional charge of that which is said. Having no way of indicating tone is a recipe for disaster, resulting in an avalanche of smiley faces after a dangerously ambiguous text message. It is not for nothing that Amharic has a sign to identify sarcasm (called ‘temherte slaq’). on the other hand, raising the ‘beware irony’ flag would impoverish its deliciously mysterious ways and where would we be without Jane Austen’s subtle ways of saying one thing and meaning another?

When constant availability makes us minimise the effort and time we devote to messages, one may assume that punctuation is doomed. After all, December 2019 saw the demise of the Apostrophe Protection Society, because the ‘ignorance and laziness present in modern times have won’, according to its former president. Yet studies on the use of the full stop in text messaging have shown that we do care about punctuation, even in a medium that promises endless continuation. When is it time to not send another text back? A full stop, the study suggests, comes across as aggressive and cuts conversation short. Perhaps a new mark is necessary?

Florence Hazrat is a Fellow of English at the University of Sheffield, working on the bracket in Renaissance literature.

'文學, 語學' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 왜 ‘대가리’는 비속어가 되었을까? (0) | 2020.01.31 |

|---|---|

| On the Hatred of Literature (0) | 2020.01.28 |

| Kafka and Dickens: A Case Study (0) | 2020.01.17 |

| James Wood: What is at Stake When We Write Literary Criticism? (0) | 2020.01.17 |

| Herman Melville the Poet (0) | 2020.01.06 |