Colonial Graveyard at Lexington, by Childe Hassam, c. 1891. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly.

Tombstones have always been tools of memory. “If a man do not erect in this age his own tomb ere he dies, he shall live no longer in monument than the bell rings and the widow weeps,” Benedick warned in Shakespeare’s sixteenth-century play Much Ado About Nothing. And few want to be forgotten, as the rows of carved granite and marble that fill cemeteries across the United States attest—even if the methods of rendering that remembering into a symbol or setting have changed and the context of these memorials has altered enough to make it hard to understand what we were supposed to remember in the first place.

The image of cemeteries that people in the United States might be familiar with—verdant hills and quiet—is a product of changes in how the living chose to remember the dead that culminated in the nineteenth century. In previous centuries people were often memorialized as part of a collective, whether that was a church, society, or family. In the Victorian era, the emphasis was much more on the individual and their glory, both on this earth and in a believed next life. The American rural cemetery movement that established many of the spaces we know today expelled the dead from the urban centers. There they had been part of neighborhoods in churchyards, private burial grounds, and potter’s fields. The movement relocated burials to garden-like spaces where the dead could be mourned in rustic settings that didn’t impede city development. For the elite, this meant more space for elaborate memorials and mausoleums; for the middle class, there were the orderly lines of plain granite tombs promoted by the newly burgeoning funeral industry. For the marginalized, the public burial grounds were also pushed to the edges but often in more hidden areas, such as New York’s Hart Island, where they were interred in mass graves.

Before the nineteenth century, death in the United States, like life, largely revolved around religion. Those who were part of a congregation were often buried in the churchyard or the crypts underneath the church. An American Puritan burial ground mirrored the traditions of England and could appear grim, with its headstones adorned with skeletons extinguishing candles, gnawing on bones, and lounging with scythes as if resting from a busy day of harvesting souls. As Francis Y. Duval and Ivan B. Rigby, who spent two decades researching early American gravestone art through photography, plaster casts, and articles, noted in their 1978 book Early American Gravestone Art in Photographs, these seventeenth-century burial grounds were visually expressive at a time when meetinghouses and churches did not have religious imagery. “The secular life was not allowed to intrude on the sanctity of these buildings,” they wrote. “But burial grounds were outside ecclesiastical jurisdiction: even though gravestone carvings glorified the destiny of all men—death and the resurrection of the soul—they were aimed at the edification of the living.” Parishioners walking the burial grounds would see these animated corpses and flying hourglasses as reminders of their own future decay and the fate of their souls. The warnings of death and its eternal judgment that punctuated sermons found an evocative outlet and a corporeal form in these tombstones.

This Great Awakening—a time of religious revival in the English colonies in North America—focused on personal salvation. In 1741 one of the most famous preachers of the era, Jonathan Edwards, famously warned that hell was real and we were all “sinners in the hands of an angry god.” This idea of memento mori—the Latin freely translates as “remember you will die”—developed in Christianity not just as a reminder of the brevity of life but also as the need to consider one’s salvation in the afterlife. Where funereal imagery in classical antiquity tended toward more of a carpe diem spirit, the macabre symbols of death preferred by eighteenth-century Christians—skulls, decaying corpses, and the Grim Reaper—were visceral calls for the living not to cling to earthly rewards and dwell instead on how their ultimate fate in heaven or hell would be decided by this fleeting existence and its temptations to sin.

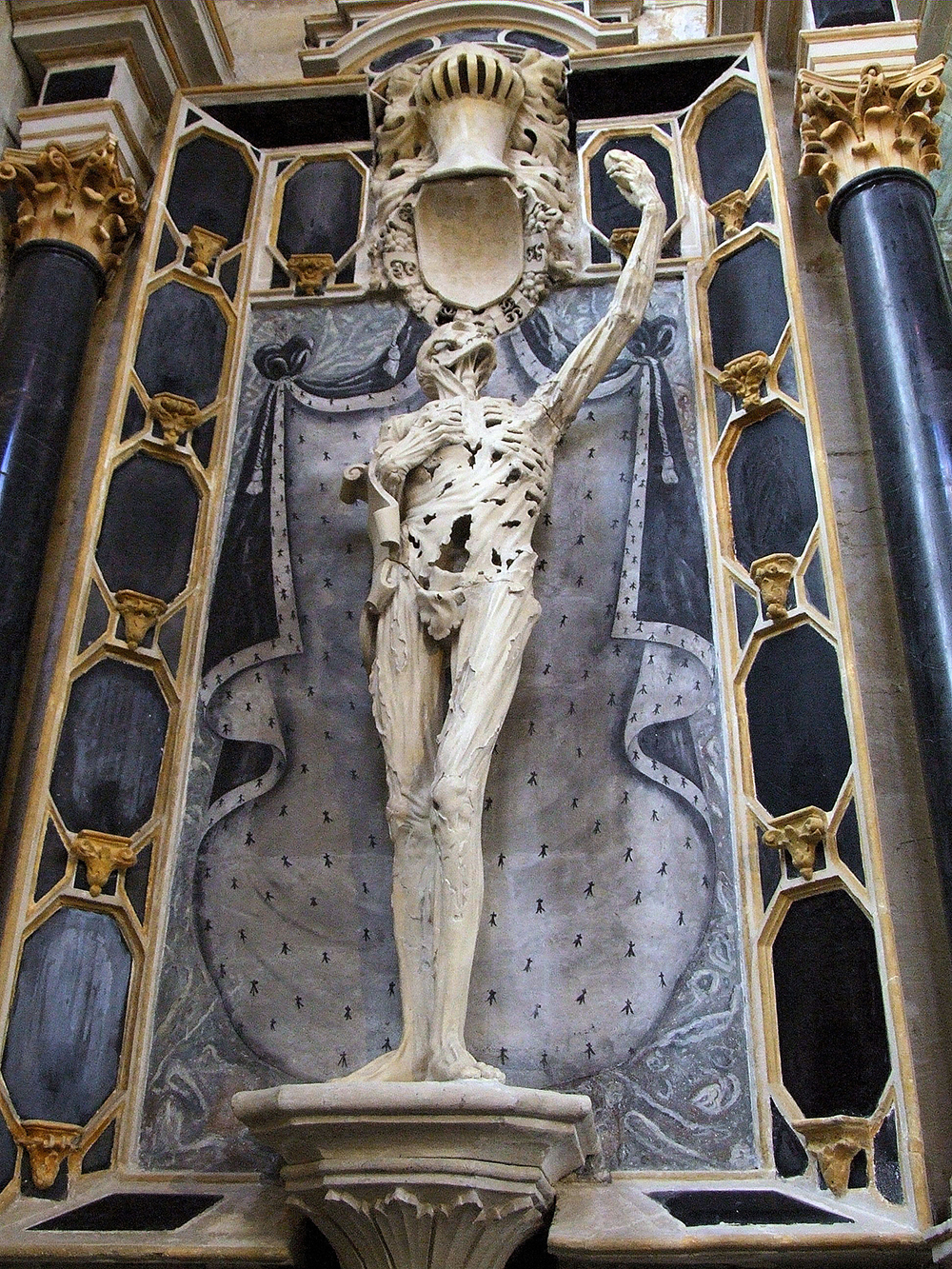

The tombstones appearing in colonial graveyards had a forebear in the transi tombs of the late Middle Ages. Also known as cadaver monuments, these sculptures found in European churches featured representations of rotting cadavers, sometimes accompanying an effigy of the living person. Examples continued into the late Gothic period, with one of the most dramatic being the cadaver tomb of René de Chalon in the church of Saint-Étienne in Bar-le-Duc, France, sculpted with detailed realism between 1544 and 1557 by Ligier Richier. It memorializes the Prince of Orange, who died at twenty-five, as a rotting corpse standing upright and holding his arm aloft. He appears dramatically animated at the same time that his flesh is falling apart. A viewer cannot forget that all that made them human will one day dissolve and become indistinguishable from dirt.

One of the most popular memento mori epitaphs of the colonial era can still be read on the 1769 tombstone of James Davis, “late Smith of the Royal Artillery,” in Trinity Churchyard in Lower Manhattan:

Behold and See as you Pass By

As you are Now so once was I

As I am Now you Soon will Be

Prepare for Death and Follow Me.

Made from Portland brownstone (the same sandstone quarried in Connecticut seen on row houses around New York City), the tombstone is decorated with a flying soul: a cherubic face bordered by two wings. Earlier carvings of winged effigies—often interpreted as the flight of the soul after death or the regeneration of the deceased—were often represented with death’s heads or a grim skull instead of the angelic visage. By the time Davis was memorialized in 1769, the flying soul had largely supplanted skulls as a gentler reminder of death.

The name cemetery—initially applied to the Roman catacombs and derived from the Greek “koimeterion” or “sleeping place”—was introduced to memorial spaces in the nineteenth century, replacing the more visceral “burying” or “burial” ground. And as the word for burial ground grew softer, so did its imagery: flying souls replaced death’s heads, flying birds replaced flying souls, and sleeping bodies supplanted skeletons. Death was but a slumber from which one would wake and receive the afterlife’s reward. The surrounding landscapes would reflect this more sentimental era of death.

By the nineteenth century, as cities such as New York and Boston became more crowded, a desire to recapture the pleasures of nature had emerged. City officials were also increasingly concerned over the sanitary conditions of the old burial grounds. An 1823 report given to a special committee of the Board of Health about a yellow fever epidemic in New York describes how lime was poured across the city to control “miasmas,” or bad air, which were believed to be spreading the disease. At Trinity Churchyard “fifty-two casks of lime” were “slackened upon the spot and spread upon the graves. The whole of this burying ground is represented as being at that time very offensive.” Soon burial restrictions were established within New York City, with an 1823 ordinance forbidding burials in Lower Manhattan and then, in 1852, another ordinance banning them below 86th Street. The dead were no longer welcome in Manhattan.

Boston physician Jacob Bigelow was also concerned about the unsanitary conditions in cemeteries. In 1825 he led a meeting of civic leaders to address the public health concerns around old burial grounds—where bodies scarcely had time to decompose before the ground needed to be reopened to admit another—and discuss the potential for a new kind of space that would elevate nature. As he argued in his speech “A Discourse on the Burial of the Dead,” presented in 1831 to the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, “when nature is permitted to take its course, when the dead are committed to the earth under the open sky, to become early and peacefully blended with their original dust, no unpleasant association remains.” Rather than placing the dead under ominous skulls and bones in festering burial grounds, why not let them rest eternally in a rustic landscape where they would have room to become one with nature? This change, Bigelow believed, could alleviate societal anxiety around death.

That year a Massachusetts Horticultural Society committee implemented Bigelow’s idea in Cambridge. on seventy-two acres that featured forests, wetlands, and hills, Mount Auburn Cemetery was founded. “We stand, as it were, upon the borders of two worlds,” said U.S. Supreme Court justice Joseph Story at a dedication ceremony on September 24 of that year. He exalted the natural setting and how its cycles embodied ideas of salvation, from the “tree that sheds its pale leaves with every autumn, a fit emblem of our own transitory bloom,” to “the evergreen, with its perennial shoots, instructing us that ‘the wintry blast of death kills not the buds of virtue.’ ” He concluded by declaring, “Here let us erect the memorials of our love, and our gratitude, and our glory.”

Mount Auburn’s ensuing popularity inspired a wave of rural cemeteries around the country, including Bangor, Maine’s Mount Hope Cemetery, founded in 1834; Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery, founded in 1836; and Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, founded in 1838. The public flocked to them not only to mourn but also to stroll among the trees and tombs and maybe spread out a picnic next to an obelisk or pick up a souvenir stereoscopic image. When landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing, who had helped design the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, argued for more public parks and gardens in the 1840s and ’50s, he focused on this booming rural cemetery movement. Jackson wrote in 1848 that, based on “the crowds of people in carriages, and on foot, which I find constantly thronging Green-Wood and Mount Auburn, I think it is plain enough how much our citizens, of all classes, would enjoy public parks on a similar scale.”

Death may come for all—“There is no armor against Fate,” as playwright and poet James Shirley wrote in his seventeenth-century poem “Death the Leveller”—but memorials for the departed have never been equal. Rather than joining the dead together in a utopic natural terrain, the rural cemetery was divided by wealth and class.

Roomier burial grounds also allowed for greater exaltations of individuals. Whereas the headstones in colonial churchyards tend to appear uniform, reflecting that these people had been interred as part of a congregation, a rural cemetery is ostentatious, with monuments seeming to compete in ornamentation, height, and grandeur. Tombs were a status symbol, as was prime grave real estate, located on hills or alongside lakes. All the class separation of life continued in death. Although some perceived the rural cemetery, without the church oversight of colonial graveyards, as a form of democratization, in many ways it made the divisions even deeper, including over who was buried in the ground and who was preserved in a granite monolith.

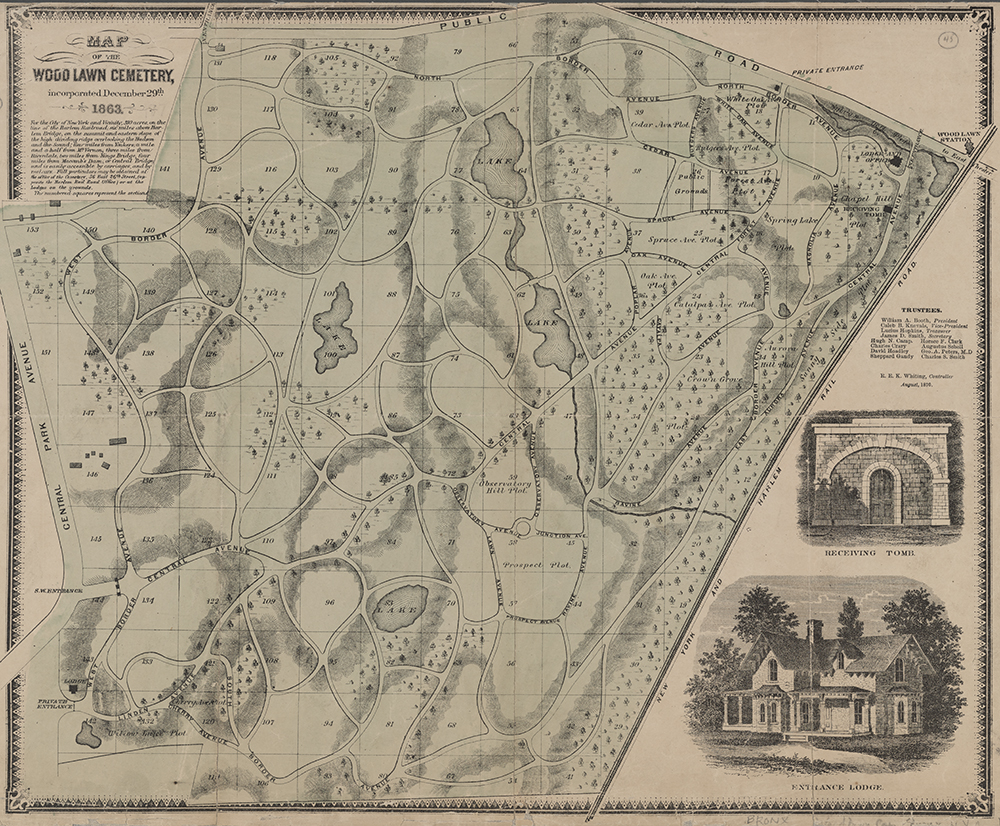

This trend accelerated with the Gilded Age, whose tycoons were buried like emperors. Robber baron Jay Gould’s mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx resembles the Parthenon; down the road, Frank Winfield Woolworth’s mausoleum is an Egyptian Revival temple guarded by two bare-chested sphinxes. While some tombs used broken columns as reminders of mortality—symbolizing that even ruin comes to once great civilizations—this borrowing from the past mostly suggested a sense of permanence and a person’s place in the history of human greatness.

For people who weren’t wealthy enough to commission their own personalized monuments, the growing funeral industry provided mass-produced versions, including in the catalogues of Sears, Roebuck and Co. Architectural critic Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer devoted a whole chapter of her 1893 book Art Out-of-Doors to cemeteries, arguing that in “telling other people that we loved our dead, we could consent to speak less loudly and more carefully.” By 1915 certain styles were so ubiquitous that Monumental News published a satirical cartoon titled “Swan Song of Some Dead Types of Monuments,” including the “oratorical angel” and “semi-finished horror” awaiting the hook on a stage.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that the rural cemetery was followed by what came to be called the “landscape-lawn plan,” pioneered by landscape gardener Adolph Strauch at Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the late 1850s. It regulated tombstone height, banned iron fences, and promoted a unified appearance. It was also easier to maintain and more affordable, which led to its adoption across the country.

Many of the nineteenth-century rural cemeteries were founded on what were then the outskirts of cities and are now surrounded by development while running out of space for traditional burials. Families of the interred have moved away or completely died out, or they may have simply lost interest in visiting the graves of relatives they never knew. Locks on crypt doors have caked with rust; small tombstones have sunk into the earth and are barely visible above the grass. Metal chairs placed in mausoleums in expectation of visitors are covered with dust. Although these cemeteries opened with a spirit of respectful recreation, offering carriage rides and picnics alongside the tombs, visitors have thinned considerably over the years. With the opening of museums and the public park movement of the later nineteenth century, fewer of the living wanted to pair their walks outside and sculpture appreciation with the dead.

For other perspectives and narratives about remembering that we will all become the past, explore Memory, the Winter 2020 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.