Does an event have to be true in order to be accepted as true, or does belief in the truth of an event already make it true, even if the thing that supposedly happened did not happen? And what if, in spite of your efforts to find out whether the event took place or not, you arrive at an impasse of uncertainty and cannot be sure if the story someone told you on the terrace of a café in the western Ukrainian city of Ivano-Frankivsk was derived from a little known but verifiable historical event or was a legend or a boast or a groundless rumor passed on from a father to a son? Even more to the point: If the story turns out to be so astounding and so powerful that your mouth drops open in wonder and you feel that it has changed or enhanced or deepened your understanding of the world, does it matter if the story is true or not?

Circumstances led me to Ukraine in September 2017. My business was in Lviv, but I took advantage of an off-day to travel two hours to the south and spend the afternoon in Ivano-Frankivsk, where my paternal grandfather had been born sometime in the early 1880s. There was no reason to go there except curiosity, or else what I would call the lure of a counterfeit nostalgia, for the fact was that I had never known my grandfather and still know next to nothing about him. He died 28 years before I was born, a shadow-man from the unwritten, unremembered past, and even as I traveled to the city he had left in the late 19th or early 20th century, I understood that the place where he had spent his boyhood and adolescence was no longer the place where I would be spending the afternoon.

Still, I wanted to go there, and as I look back and ponder the reasons why I wanted to go, perhaps it comes down to a single verifiable fact: The journey would be taking me through the bloodlands of Eastern Europe, the central horror-zone of 20th-century slaughter, and if the shadow-man responsible for giving me my name had not left that part of the world when he did, I never would have been born.

What I already knew in advance of my arrival was that before it became Ivano-Frankivsk in 1962 (in honor of Ukrainian poet Ivan Franko), the 400-year-old city had been known variously as Stanislawów, Stanislau, Stanislaviv, and Stanislav, depending on whether it had been under Polish, German, Ukrainian, or Soviet rule. A Polish city had become a Hapsburg city, a Hapsburg city had become an Austro-Hungarian city, an Austro-Hungarian city had become a Russian city in the first two years of World War I, then an Austro-Hungarian city, then a Ukrainian city for a short time after the war, then a Polish city, then a Soviet city (from September 1939 to July 1941), then a German-controlled city (until July 1944), then a Soviet city, and now, following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, a Ukrainian city.

At the time of my grandfather’s birth, the population was 18,000, and in 1900 (the approximate year of his departure) there were 26,000 people living there, more than half of them Jews. By the time of my visit, the population had grown to 230,000, but back during the years of the Nazi occupation the number had been somewhere between 80,000 and 95,000, half Jewish, half non-Jewish, and what I had already known for several decades by then is that after the German invasion in the summer of 1941, 10,000 Jews had been rounded up and shot in the Jewish cemetery that fall and by December the remaining Jews had been herded into a ghetto, from which 10,000 more Jews had been shipped off to the Belźec death camp in Poland, and then, one by one and five by five and twenty by twenty throughout 1942 and early 1943, the Germans had marched the surviving Jews of Stanislau into the woods surrounding the city and had shot them and shot them and shot them until there were no Jews left—tens of thousands of people murdered by a bullet to the back of the head and then buried in the common pits that had been dug by the murdered ones before they were killed

A kind woman I had met in Lviv took charge of organizing the trip for me, and because she had been born and raised in Ivano-Frankivsk and still lived there, she knew where to go and what to see and even went to the trouble of enlisting someone to drive us there. A young lunatic with no fear of death, the driver barreled down the narrow two-lane highway as if he were auditioning for a stuntman’s job in a racing-car movie, taking inordinate risks to pass every car in front of us as he calmly and abruptly swerved into the other lane even as oncoming cars hurtled toward us, and several times during the trip it occurred to me that this dull, overcast afternoon on the first day of autumn 2017 would be my last day on earth, and how ironic it was, I said to myself, and yet how terribly fitting, that I should have come all this way to visit the city my grandfather had left more than a hundred years ago only to die before I got there.

Fortunately, the traffic was sparse, a mix of fast-moving cars and slow-moving trucks and, at one point, a horse-drawn wagon loaded down with a massive pile of hay, moving at one-tenth the speed of the slow-moving trucks. Stout, thick-legged women with babushkas on their heads trudged along the side of the road carrying plastic bags filled with groceries. Except for the plastic bags, they could have been figures from two hundred years ago, Eastern European peasant women trapped in a past so old that it had lived on into the 21st century. We passed through the outskirts of a dozen small towns as large, recently harvested fields stretched out on either side of us, but then, about two-thirds of the way there, the rural landscape dissolved into a no-man’s-land of heavy industry, the most spectacular example being the gargantuan power plant that suddenly rose up before us on our left.

If I have not scrambled what the kind woman told me in the car, that monolithic installation supplies Germany and other Western European countries with the bulk of their electricity. Such are the contradictory truths of that 800-mile-wide buffer state locked in the slaughter-lands between East and West, for even as Ukraine feeds one side with the electrical juice to light the lights and keep things running, on the other side it goes on spilling blood to defend its shrinking, embattled territory.

Ivano-Frankivsk turned out to be an attractive place, a city that bore no resemblance to the disintegrating urban ruin I had pictured in my mind. The clouds had dispersed just minutes before we got there, and with the sun shining and scores of people walking around in the streets and public squares, I was impressed by how clean and well-ordered it was, not some provincial backwater stuck in the past but a small contemporary city with bookstores, theaters, restaurants, and a pleasing blend of new and old architecture, the old having survived in the 17th- and 18th-century buildings and churches constructed by the Polish founders and their Hapsburg conquerors.

I would have been content to wander around for two or three hours and then head back, but the kind woman who had orchestrated the visit understood that my purpose in going there had been connected to my grandfather, and because my grandfather had been a Jew, she thought it might be helpful for me to talk with the one rabbi left in town, the spiritual leader of Ivano-Frankivsk’s last remaining synagogue—which proved to be a solid, handsomely designed building from the first years of the 20th century that had somehow managed to come through the Second World War with only minor damages, all of which had long since been repaired.

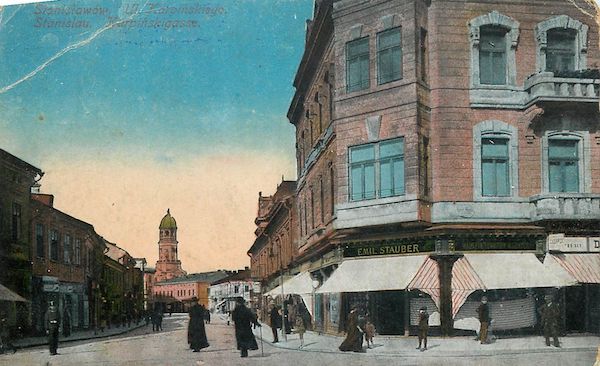

Stanislau, circa 1912.

Stanislau, circa 1912.I’m not sure what I thought, but I had no objection to talking to the rabbi, since he was probably the only person still above ground anywhere in the world who might—just might—have been able to tell me something about my family, that nameless horde of invisible ancestors who had scattered and died and subsequently vanished from the realm of the knowable, for it was all but certain that their birth records had been destroyed by a bomb or a fire or the signature of some over-zealous bureaucrat at some point in the past hundred years. Talking to the rabbi would be a useless errand, I realized, a by-product of the counterfeit nostalgia that had brought me to the city in the first place, but there I was, there for that day and that day only, with no thought of ever coming back, and what harm would it do to ask some questions and see if any of them could be answered?

There were no answers. The bearded, Orthodox rabbi welcomed us into his office, but beyond telling me what I had already known—that Auster was a name common among the Jews of Stanislav and nowhere else—and then digressing briefly into a story from the war about a woman named Auster who had eluded capture by the Germans by hiding in a hole for three years and after those three years had emerged from the hole insane, a mad person for the rest of her life—he had no information to give me. A hectic, jittery man who chain-smoked ultra-thin cigarettes throughout the conversation, stubbing them out after just a few puffs and then pulling fresh ones from a plastic bag on his desk, he was neither friendly nor unfriendly, simply distracted, a man with other things on his mind and, as far as I could tell, too busy with his own concerns to show much interest in his American visitor or the woman who had arranged the meeting.

By most accounts, there are no more than two or three hundred Jews living in Ivano-Frankivsk today. It is unclear how many of them practice their religion or attend services at the synagogue, but from what I had witnessed an hour before I met the rabbi, it would seem that no more than a small fraction of that diminished number take part. By pure chance, my visit happened to fall on Rosh Hashanah, one of the most sacred days on the liturgical calendar, and only 15 people had been present in the sanctuary to listen to the sounding of the shofar that ushers in the new year, 13 men and two women. Unlike their counterparts in Western Europe and America on such occasions, the men had not been wearing dark suits and ties but nylon windbreakers, and their heads had been covered by red and yellow baseball caps

We went back outside and wandered around for an hour, an hour and a half, perhaps longer. The kind woman had arranged for me to talk with another person at four o’clock, a poet from Ivano-Frankivsk who had apparently spent years delving into the city’s history, but for now there was time to explore some of the places we had missed earlier, and so we pushed on with our rambles until we had covered a large part of the city. The sun was blazing by then, and in that beautiful September light we drifted onto a large, open square and found ourselves standing in front of the Church of the Holy Resurrection, an 18th-century baroque cathedral that is considered to be the most beautiful Hapsburg structure from the years when Ivano-Frankivsk had been known as Stanislau. As was the case with other beautiful churches and cathedrals I had visited in Western European towns and cities, I assumed it would be mostly empty when we walked in, with no one about except for some random tourists and their cameras. I was wrong.

This was not Western Europe, after all, it was the far western edge of what had once been the Soviet Union, a city located in the province of Galicia at the far eastern edge of the former Austro-Hungarian empire, and the church, which was not Roman Catholic or Russian Orthodox but Greek Catholic, was nearly full with people, none of them tourists or scholars of baroque architecture but local citizens who had come to pray or to think or to commune with themselves or the Almighty in that vast stone space with September light pouring through the stained-glass windows. There must have been a hundred people, perhaps two hundred, and what struck me most about that large, silent crowd was how many young people were in it, a good half of the total number, men and women in their early twenties sitting in pews with their heads bowed or on their knees with their hands clasped and their heads turned upward and their eyes fixed on the light pouring through the stained-glass windows.

An ordinary weekday afternoon, with nothing to distinguish it from any other day except that the weather had become exceptionally fine, and on that radiant afternoon the Church of the Holy Resurrection was full of young people who were neither at work nor sitting around in outdoor cafés but kneeling on the stone floor with their hands clasped and their heads turned upward in postures of prayer. The chain-smoking rabbi, the red and yellow baseball caps, and now this.

And after this, which had come after that, it made perfect sense to me that the poet turned out to be a Buddhist. And no, he was not some New Age convert who had read a couple of books about Zen but a long-time practitioner who had just returned from a four-month stay at a monastery in Nepal, a serious man. And also a poet, and also a student of the city in which my grandfather had been born. He was a large, hulking fellow with meaty hands and an affable manner, a clear-eyed, thoughtful person dressed in European clothes who mentioned his commitment to Buddhism only in passing, which I took to be an encouraging sign, and therefore I trusted him and felt I could depend on him to tell me the truth. The meeting took place just two and a half years ago, but the odd thing about our encounter is that even after such a short time and even though I have thought about it almost every day since, I am unable to remember a single thing he told me about the city before he mentioned the wolves. once he began to tell that story, everything else was obliterated.

We were sitting on the terrace of a café looking out at the largest square in the city, the central hub of Stanislau-Stanislav-Ivano-Frankisvk, a broad space awash in sunlight with no cars and a great many people walking from here to there in all directions, not one of them making a sound as I remember it, nothing but a mass of silent people passing in front of me as I listened to the poet tell the story. We had already established the fact that I was familiar with what had happened to the Jewish half of the population between 1941 and 1943, but when the Soviet army rolled in to capture the city in July 1944, he said, just six weeks after the Allied invasion of Normandy, not only had the Germans already cleared out but the other half of the population was gone as well. They had all run away in one direction or another, east or west, north or south, which meant that the Soviets had conquered an empty city, a domain of nothingness. The human population had dispersed to the four winds, and instead of people the city was now inhabited by wolves, hundreds of wolves, perhaps thousands of wolves.

Horrible, I thought, so horrible that it contained the horror of the most horrible dream, and suddenly, as if rising up from a dream of my own, the poem by Georg Trakl came rushing back to me—Eastern Front, which I had first read 50 years earlier, had read again and again until I knew it by heart and then had retranslated for myself, the World War I poem from 1914 written about Gródek, a Galician city not far from Stanislau that ends with the stanza:

A thorn-studded wilderness girds the city.

From bloody stairs the moon

Chases terrified women.

Wild wolves have stormed through the gates.

How did he know this? I asked.

His father, he said, his father had told him about it many times, and then he went on to explain how his father had been a young man in 1944, barely into his twenties, and after the Soviets took control of Stanislau, henceforth to be known as Stanislav, he had been conscripted into the army unit assigned to the task of exterminating the wolves. The job took several weeks, he said, or perhaps it was several months, I can’t quite remember, and once Stanislav was fit for human habitation again, the Soviets repopulated the city with military personnel and their families.

I looked out at the square in front of me and tried to imagine it in the summer of 1944, all the people walking around on their errands from here to there suddenly gone, erased from the scene, and then I began to see the wolves, dozens of wolves loping through the square, moving along in small packs as they searched for food in the abandoned city. The wolves are the endpoint of the nightmare, the farthest outcome of the stupidity that leads to the devastations of war, in this case the three million Jews murdered in those eastern bloodlands along with countless other civilians and soldiers from other religions and no religion, and once the slaughter has ended, wild wolves come crashing through the gates of the city. The wolves are not just symbols of war. They are the spawn of war and what war brings to the earth.

I have no doubt that the poet believed he was telling me the truth. The wolves were real to him, and because of the calm conviction in his voice as he told me the story, I accepted them as real myself. Admittedly, he had not seen the wolves with his own eyes, but his father had, and why would a father tell his son such a story if it hadn’t been true? He wouldn’t, I told myself, and when I left Ivano-Frankivsk later that afternoon, I was convinced that for a short time after the Russians had taken control of Stanislav from the Germans, wolves had ruled the city.

In the weeks and months that followed, I did what I could to investigate the matter more thoroughly. I talked to a friend who had contacts with historians at the university in Lviv (formerly known as Lvov, Lwów, and Lemberg), in particular one woman who specialized in the history of the region, but in none of her past research had she ever stumbled across anything about the wolves of Stanislav, she said, and when she looked into the matter more thoroughly herself, she failed to turn up a single reference to the story the poet had told me. What she did turn up, however, was a short film that documents the capture of the city by Soviet troops on July 27, 1944, and when a video of that film was sent to me, I was able to watch it for myself as I sat in the same chair I am sitting in now.

Fifty or a hundred soldiers in neatly ordered ranks march into Stanislav as a small crowd of well-dressed, well-fed citizens cheers their arrival. The scene then plays out again from a slightly different angle, showing the same fifty or a hundred soldiers and the same, well-dressed, well-fed crowd. The film then cuts away to an image of a collapsed bridge, and then, before it dribbles to its conclusion, cuts back to the original shot of the soldiers and the cheering crowd. The soldiers might have been genuine soldiers, but in this instance they had been asked to play the role of soldiers, just as the actors who had been directed to play the cheering crowd were performing their roles in a crudely edited, unfinished propaganda film intended to glorify the heroic goodness and valor of the Soviet Union.

Needless to say, not one wolf appears anywhere in the film.

Which brings me back to the place where I began and the question that has no answer: What to believe when you can’t be sure whether a supposed fact is true or not true?

In the absence of any information that could confirm or deny the story he told me, I choose to believe the poet. And whether they were there or not, I choose to believe in the wolves.

*

Brooklyn, March 27, 2020

(In Covid-19 lockdown)

Featured art

The Struggle for Existence

George Bouverie Goddard (1879)