HistoryExplainer

The Korean War never technically ended. Here’s why

Seventy years ago, conflict erupted over who would control the Korean Peninsula. It stoked tensions that still roil today—and changed how wars are waged.

A South Korean infantry officer directs troops on the front lines of the Korean War on August 10, 1950. The conflict had erupted earlier that summer when North Korea invaded South Korea. Fighting would last for three years—and a peace treaty was never signed.

By Erin Blakemore

The National Geographic

PUBLISHED June 24, 2020

On June 25, 1950, North Korea’s surprise attack on South Korea sparked a war that pitted communists against capitalists for control of the Korean Peninsula. Fought between 1950 and 1953, the Korean War left millions dead and North and South Korea permanently divided.

But though it was dubbed the “forgotten war” in the United States due to the lack of attention it received during and after the conflict, the Korean War’s legacy is profound: Not only does it still shape geopolitical affairs—it technically never ended—but it also set a precedent for American presidents to wage wars without consent of Congress.

The war had its roots in Japan’s occupation of Korea between 1910 and 1945. As World War II came to an end and the Allied powers began dismantling Japan’s empire, Korea’s fate became a bargaining chip between the United States and the U.S.S.R. The former allies distrusted each other, and in 1948, as a check on one another’s influence, they established two separate Korean nations demarcated by a border at the 38th parallel, the line of latitude that crosses the Peninsula. North Korea would be a socialist state led by Kim Il-sung and backed by the U.S.S.R., and South Korea a capitalist state led by Syngman Rhee and backed by the United States. (Here's how a National Geographic map helped divide the peninsula after WWII.)

View Images

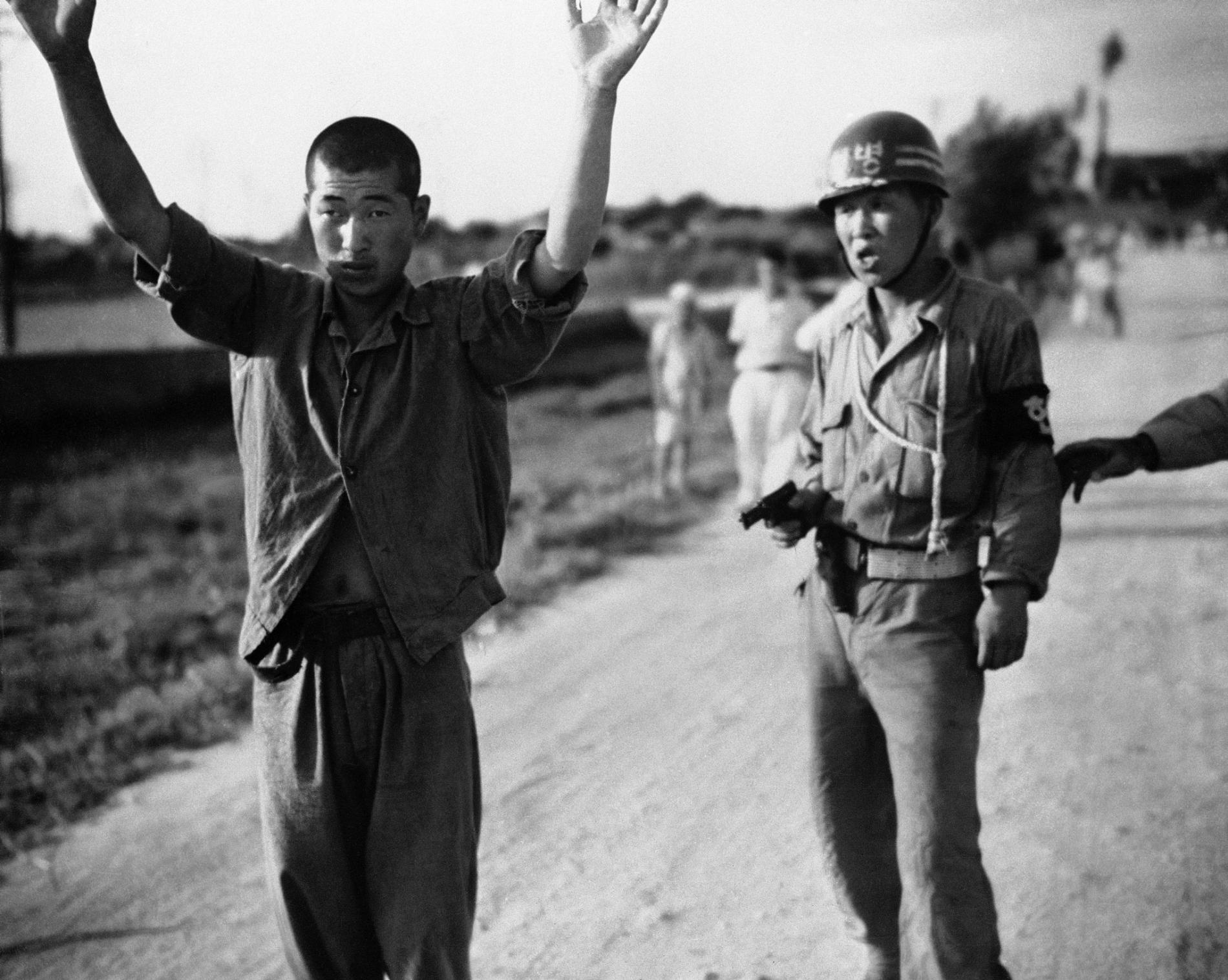

A South Korean military policeman marches a North Korean prisoner of war to a stockade in South Korea on July 21, 1950. The fate of POWs was a major sticking point in negotiations to end the Korean War.

Photograph by AP

The hope was that the two nations would balance power in East Asia, but it quickly became clear that neither state saw the other as legitimate. After a series of border skirmishes, North Korea invaded its southern neighbor in June 1950. This invasion set off a proxy war between the two nuclear powers—and the first conflagration of the Cold War.

The U.S. pressed the newly created United Nations Security Council to authorize the use of force to aid South Korea, and President Harry Truman committed troops to the cause—without seeking the approval of Congress, which alone has the power to declare war. It was the first time the United States entered a large-scale foreign conflict without an official declaration of war.

“We are not at war,” Truman told the press on June 29, 1950. “[South Korea] was unlawfully attacked by a bunch of bandits which are neighbors of North Korea.” Despite questions about whether Truman overstepped presidential authority, U.S. involvement in the conflict was officially chalked up to a “police action.”

View Images

U.S. soldiers share a light for cigarettes amid smoldering ruins in Seoul, South Korea, in September 1950. The Korean War marked the first time a U.S. president committed troops to a large-scale foreign conflict without a Congressional declaration of war.

Photograph by Max Desfor, AP

The U.S. had assumed the war would be quickly won, but that notion was soon proved wrong. In the early days of the conflict, UN forces pushed into North Korea and toward the border of communist China, which responded by deploying more than three million troops to North Korea. Meanwhile, the U.S.S.R. supplied and trained North Korean and Chinese troops, and sent pilots to fly missions against UN forces.

By summer 1951, troops had settled into a dangerous stalemate around the 38th parallel. Casualties mounted. Negotiations began in July, but both sides faltered at the negotiating table over the fate of prisoners of war. Though many POWs captured by American forces did not want to go back to their home countries, both North Korea and China insisted on their repatriation as a condition of peace. During a tense series of prisoner exchanges ahead of the armistice in 1953, more than 75,000 communist prisoners were returned; over 22,000 defected or sought asylum.

On July 27, 1953, North Korea, China, and the United States signed an armistice agreement. South Korea, however, objected to the continued division of Korea and did not agree to the armistice or sign a formal peace treaty. So while the fighting ended, technically the war never did.

View Images

On April 26, 1953, men, women, boys, and soldiers stand beneath a waving banner during a demonstration in Seoul against resumption of the Korean peace talks.

Photograph by AP

It is still unclear how many people died in the Korean War. Nearly 40,000 American troops, and an estimated 46,000 South Korean troops, were killed. Casualties were even higher in the north, where an estimated 215,000 North Korean troops and 400,000 Chinese troops died. But the vast majority of the dead—up to 70 percent—were civilians. As many as four million civilians are thought to have been killed, and North Korea in particular was decimated by bombing and chemical weapons.

Many troops were also unaccounted for at the end of the war. About 80,000 South Korean troops were caught in North Korea when the war ended. Though the North has denied taking them prisoner, defectors and South Korean officials report that the trapped soldiers were put to work as forced laborers. The whereabouts of the remains of most of those POWs will never be known. In June 2020, however, the U.S. identified and returned 147 South Korean POWs whose remains had been handed over by North Korea in 2018. Meanwhile, more than 7,500 U.S. troops are still missing.

View Images

In August 2000, a South Korean woman touches the face of her North Korean son as she sees him for the first time since they were separated during the Korean War. Though conflict still simmers on the Korean Peninsula, many hope to see the two countries reunified.

Photograph by David Guttenfelder, AP/Nat Geo Image Collection

Seventy years after the war began, the two Koreas are still divided. Hopes for reunification briefly flickered in 2000, when both nations issued a joint declaration that they would make “concerted efforts” to reunify, and again in 2018 after a summit in which the countries’ leaders shook hands and hugged. But those hopes have slowly faded, and in June North Korea blew up a joint office that served as an embassy between the embattled nations. (See why the border between North and South Korea is normally packed with tourists.)

But while the Korean War has largely faded in the memories of Americans—overshadowed by World War II and the Vietnam War—the precedent set by Truman’s actions in Korea has been used by U.S. presidents as justification for military interventions in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, and UN missions in Bosnia and Haiti. The first-of-its-kind decision has been debated ever since. Undeclared, unresolved, and largely unremembered, the war’s unsettling legacy lives on.

'6.25 動亂史' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 김학준이 다시 쓴 6·25전쟁 16大 쟁점 (0) | 2020.06.30 |

|---|---|

| On Korean War 70th Anniversary, What Does the North's Kim Jong Un Want? (0) | 2020.06.26 |

| The Korean War “created a blood debt that is crucial to understanding North Korean behaviour ever since” (0) | 2020.06.21 |

| 한국전쟁은 어떻게 유권자들을 이념적 보수화 시켰나? (0) | 2019.01.17 |

| 박만순의 기억 전쟁 - 한국전쟁기 대전·충청지역 민간인학살 피해자들의 알려지지 않은 이야기 (0) | 2019.01.08 |