In 14th-Century Florence, Some Residents Socially Distanced While Others Hit the Bars

A contemporary debate would feel familiar to Europeans alive when the Bubonic plague arrived.

Atlas Obscura

August 19, 2020

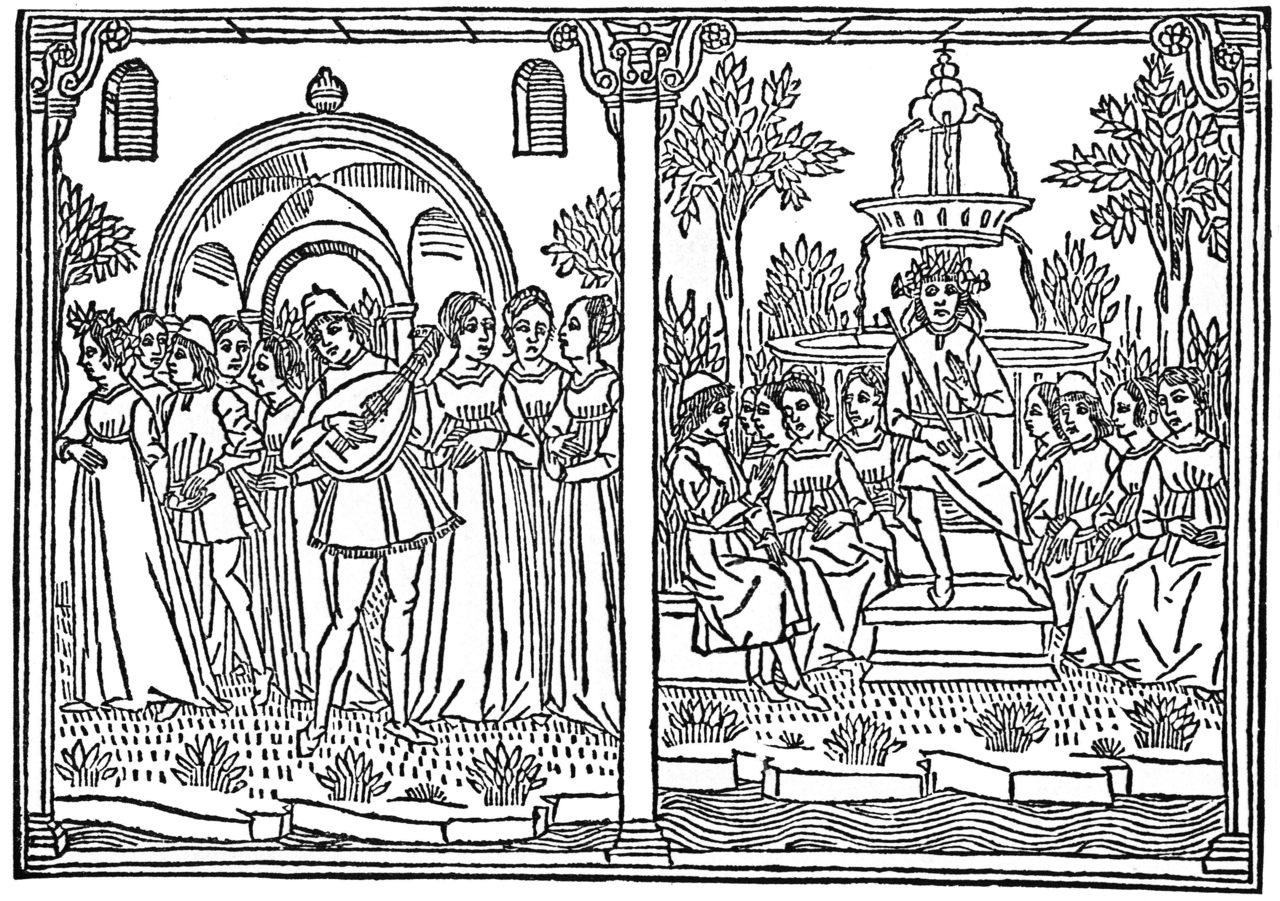

These woodcuts are from the Decameron, a collection of novellas in which young people fleeing plague-ridden Florence tell stories that often provide accounts of life during the pandemic. Charles Walker Collection / Alamy

In This Story

A global pandemic rages. In some cities, people shun society completely, while others sit in bars, downing beers and trying to forget about the disease raging around them.

But this isn’t 2020—it’s the mid 1300s. The Black Death, which arrived in Europe in 1347, ripped across the continent, killing around 50 percent of its population. Jean de Venette, a French Carmelite friar who documented the pandemic, called it “a most terrible scourge inflicted on us by God.” We now know that it was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which spread from rodents to humans through fleas. Commentators have frequently compared the time of the Black Death to the fallout from diseases including SARS, Ebola, and now COVID-19. As lockdowns around the world have begun to lift, we can extend that analysis to drinking habits.

The Decameron provides a fascinating account of how people from all social classes drank differently during the plague. In his celebrated collection of novellas, Giovanni Boccaccio describes the plague invading his home city of Florence in 1348. Food, and particularly drink, are central to this account.

Boccaccio uses mealtimes to illustrate how quickly the plague became fatal: “How many brave men […] broke fast with their kinsfolk, comrades and friends in the morning, and when evening came, supped with their forefathers in the other world.” He even describes symptoms with food metaphors, writing of “the emergence of certain tumours in the groin or the armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg.”

Vernaccia vineyards around San Gimignano, Tuscany. This fine white wine is referenced by Boccaccio’s characters who went into isolation. Giovanni Boscherino / Alamy

Florentines also reportedly sought out culinary “cures.” Tommaso del Garbo, a professor of medicine at Bologna and Perugia, advised stuffing one’s mouth with cloves, then eating “two slices of bread soaked in the best wine” as a remedy. However, confusion over what really cured the plague recurs throughout Boccaccio’s account. People began to guess at preventatives, or reject them altogether.

According to Boccaccio, two extremes emerged, and they may sound very familiar to modern readers deciding whether or not to take advantage of bars and restaurants reopening. While a lockdown wasn’t officially imposed during the Black Death, some Florentines went into voluntary hiding. They restricted their diet to simple meals and only drank small amounts of fine wine to sustain themselves; they were intent on “avoiding every kind of luxury, […] eating and drinking very moderately of the most delicate viands and the finest wines.” They believed gluttony was a root cause of plague and thought that “to live temperately and avoid all excess” would protect them. One of the fine wines they favored was likely Vernaccia; described in The Decameron as a “good white wine.” It is still considered one of Italy’s finest whites today.

Others went a different route. Florence was decimated and its population only recovered pre-plague numbers in the 1800s. Faced with almost certain death, many threw themselves among the dying for a cup of ale and maintained that “to drink freely, […] sparing to satisfy no appetite, was the sovereign remedy for so great an evil.” Pub crawls were a regular sight, with desperate citizens “resorting day and night, now to this tavern, now to that, drinking with an entire disregard of rule or measure.” A strange open-house policy emerged, as people invited passersby inside for a drink. “The owners, seeing death imminent, had become as reckless of their property as of their lives,” writes Boccaccio. Little did they know the true extent of their recklessness—scientists have since discovered that humans infected with plague pneumonia passed on infectious droplets via coughing and sneezing.

It’s understandable that Florentines felt like they needed a drink. incamerastock / Alamy

How did the two groups feel about each other? Clearly some hoped that the disease might be controlled, whereas others, consumed with desperation, resorted to binge drinking. Boccaccio describes a growing paranoia among the community: “Citizen avoided citizen, […] kinsfolk held aloof, and never met, or but rarely.” However, the author refuses to wholeheartedly condemn either party; the “fury of the pestilence” was so severe that there were no winners and no time for moral superiority. People died alone, bodies piled up, and most buildings were emptied of their former occupants.

Boccaccio himself preferred a third way: fleeing to the countryside. But for those who were unable to leave, plague-stricken Florence became a city in which “every man was free to do what was right in his own eyes.” Arguably both options had their merits.

'重要資料 모음' 카테고리의 다른 글

| スターリン、独ソ戦中にモンゴル巨大陣地 対日戦へ布石 (0) | 2020.09.05 |

|---|---|

| On This Day in 1945, Japan Released Me from a POW Camp. Then US Pilots Saved My Life (0) | 2020.08.28 |

| Hagia Sophia Past and Future (0) | 2020.08.18 |

| Korea’s 50 Richest People (0) | 2020.08.04 |

| Transnationally Asian (0) | 2020.07.22 |