The Disaster Poet

On William McGonagall, the worst famous poet in the English language.

Lapham's Quarterly

Monday, August 17, 2020

Thunderstorm with the Death of Amelia, by William Williams, 1784. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

It’s the rare story that’s equally familiar to both engineers and literature students: On December 28, 1879, a train was carrying passengers across Scotland’s River Tay from Wormit to Dundee on a very windy evening. The Tay Bridge, which had been completed only a year earlier, spanned some two miles. When it opened, it was the longest railway bridge in the world; the chief engineer was honored for his achievement with a knighthood from Queen Victoria. But this same engineer had neglected to ensure that his construction would withstand particularly heavy gales, and as the train’s six cars reached the center of the bridge’s span, the structure gave way, plunging an estimated seventy-five passengers and crew members into the river’s freezing depths. No one survived.

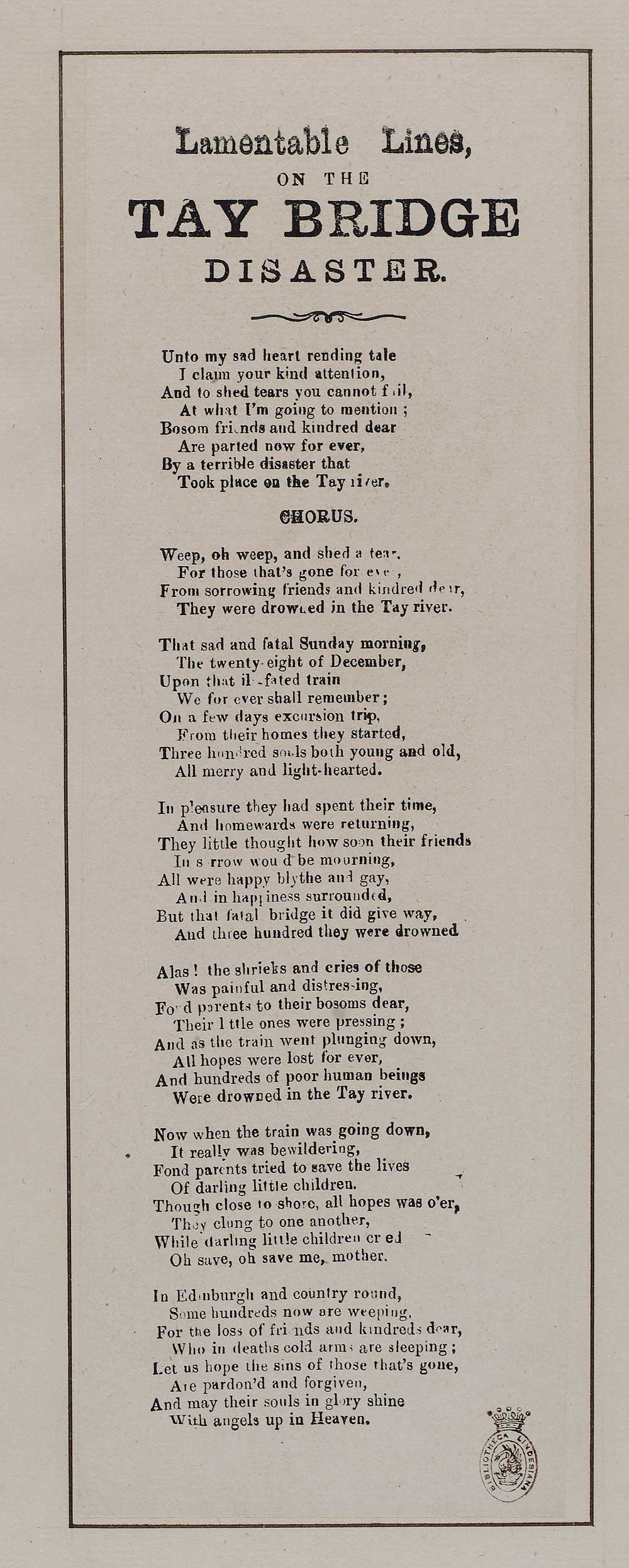

The incident made front-page news across Britain. Queen Victoria had a missive sent directly to the lord provost of Dundee: “The queen is inexpressibly shocked, and feels most deeply for those who have lost friends and relatives in this terrible accident.” (Initial reports suggested that the death toll was higher, around two hundred, further compounding the intensity of national emotions.) Despite the carnage, however, the wreck is principally known today as the occasion for one of the English language’s clumsiest poetic efforts, William McGonagall’s “The Tay Bridge Disaster.” Here is one of its infamous stanzas:

So the train mov’d slowly along the Bridge of Tay,

Until it was about midway,

Then the central girders with a crash gave way,

And down went the train and passengers into the Tay!

The Storm Fiend did loudly bray,

Because ninety lives had been taken away,

On the last Sabbath day of 1879,

Which will be remember’d for a very long time.

The syntax of the “Disaster” is tortuously arranged to hit the poem’s rhymes; its literalness preempts any possibility for gravitas or emotional weight; and its meter seems beamed in from an alien universe. Undermined by its own technical haplessness, written with the impregnable conviction of the talentless, the “Disaster” is a heartfelt paean to the doomed train passengers that—however ironically and unfortunately—better serves as a memorial to the poet’s own buffoonery.

Not unjustly, McGonagall is rarely mentioned without an epithet: some version of “the worst poet in the English language.” And by any reasonable account, any judgment based on the most universally shared values of poetics, prosody, and taste, there is little to admire in McGonagall. The rest of his corpus shares—replicates, really—the faults of “The Tay Bridge Disaster”: its lapses into bathos, its involuted syntactical structures, its rhymes so slanted as to be more or less horizontal.

There have been worse poets, of course, and as such it would be more accurate to describe McGonagall as the worst famous poet in the English language, a testament in part to the man’s powers of self-promotion and the caprices of literary history. But McGonagall’s notoriety still owes much to the singularly strange power of his own badness. There’s something, I think, in poems like “The Tay Bridge Disaster”—as well as McGonagall’s many poems on his great themes of death and destruction—that is worth examining; something that might redeem him, ever so slightly, from the annals of amusing semi-obscurity; something unsettling about his ostensibly blinkered artistic vision that might help to account for why he lingers as the patron saint of misbegotten verse.

Scotland has justifiably claimed him as its own, but in all likelihood McGonagall was born in Ireland, in 1825. His family migrated to Dundee when William was a child, and like much of the city’s population, he grew up to be a weaver. The textile business was booming then, though the apogee of the mechanical revolution wasn’t far behind. And as the industry began to make workers redundant amid its collapse in 1877, McGonagall had a conveniently timed epiphany. Sitting in his room on a spring day, he recalls, “I seemed to feel as it were a strange kind of feeling stealing over me…I imagined that a pen was in my right hand, and a voice crying, ‘Write! Write!’” He complied, writing a graceless tribute to the Scottish preacher George Gilfillan (himself a poet, although the misfortune of having been eulogized by his fellow Dundonian has been the better part of his literary legacy). McGonagall sent the results to Dundee’s Weekly News, where they were subsequently published by a deeply bemused editorial staff.

What followed over the next two and a half decades was one of the most bizarre careers in Victorian letters. The Weekly News proved a reliable publisher, though it often accompanied McGonagall’s hapless texts with scathingly ironic commentary (a courtesy they were not inclined to extend to their more traditional poetic contributors). Encouraged by what he misconstrued to be rightful artistic recognition, the poet took to local theaters to read his own works and recite Shakespearean soliloquies, whereupon he was often met with raucous crowds who either mockingly encouraged him—sometimes carrying him aloft into the streets—or pelted him with garbage.

(Contemporary accounts allege that among the objects he was barraged with were potatoes, footwear, rotten eggs, fish, sacks of soot, peas, snowballs, and, on at least one occasion, a brick.) His profile rising amid these riotous performances, McGonagall increasingly became the victim of a number of cruel pranks, which only served to inflate his own sense of vocational destiny. He trekked to Balmoral Castle seeking an audience with Queen Victoria after someone had passed him a sham letter of patronage; he was tricked into dining with an imposter posing as the dramatist Dion Boucicault; and in the last years of his life, McGonagall was made a knight of the fictional “Holy Order of the White Elephant,” an honor supposedly bestowed upon him by the king of Burma, and of which he proudly and obliviously boasted until his death.

Many of McGonagall’s poems, which he churned out at a reliable clip after his poetic conversion, were benign and banal odes to Scottish and English landscapes in the manner of a one-man lyrical tourism bureau. He writes that Crieff, a trendy nineteenth-century vacation spot, “is admirably situated from the cold winter winds / And the visitors, during their stay there, great comfort finds, / Because there is boating and fishing, and admission free, / Therefore they can enjoy themselves right merrily.” What’s more: “There is also golf courses, tennis greens, and good roads, / Which will make the traveling easier to tourists with great loads.” The specificity of McGonagall’s laundry list of amenities is at every point undermined, in his typical manner, by a penchant for recycling some wonderfully ungainly idioms. Parts of Montrose in “Bonnie Montrose,” for instance, are “most magnificent to be seen,” “most charming to be seen,” and “most beautiful to see,” in three successive stanzas. Even with their regional particularity, the poems feel perfectly interchangeable. The poem’s titles often do the work of announcing the sameness of their portrayals: “Bonnie Kilmany” and “Bonnie Callander,” “Beautiful North Berwick” and “Beautiful Village of Penicuik.”

Despite a penchant for the versified guidebook, however, the principal thematic fixture of McGonagall’s career was cataclysm. “The Tay Bridge Disaster” was only the inaugurating work in a long series of calamity chronicles. It seems as if the poet never met a catastrophe that he didn’t contrive to transform into misguided elegy. Shipwrecks were his forte, but any disaster would do, really. He memorialized the victims of fires, tornadoes, stampedes, floods, military routs, any mass-casualty event that would have found its way into the Dundee press. According to Norman Watson, McGonagall’s biographer, out of the 270 poems attributed to McGonagall, twelve are on funerals, six on fires, fifty on battles, and twenty-four on “maritime disasters.” The poems’ rote, straightforward titles compose a global charnel house of grisly incident: “The Terrific Cyclone of 1893,” “The Pennsylvania Disaster,” “The Horrors of Majuba,” “The Wreck of the Steamer ‘Stella,’ ” “The Great Yellow River Inundation in China.”

While remaining true to the general principles of McGonagallian style, these poems carried with them their own particular formal and phrasal tics. “The Pennsylvania Disaster,” written to commemorate the Johnstown Flood, is a useful case in point. The poem opens with a kind of dateline: “’Twas in the year of 1889, and in the month of June, / Ten thousand people met with a fearful doom.” The death count established, the reader adequately oriented in historical time, McGonagall moves on to narrate the horrors of the flood in his characteristic tragic mode: comically flattened affect punctuated by mannered exclamations of grief.

Oh, heaven! it was a pitiful and a most agonizing sight,

To see parents struggling hard with all their might,

To save their little ones from being drowned,

But ’twas vain, the mighty flood engulfed them, with a roaring sound.

In the end, virtually all of his poems conclude with the assertion that these events “will never be forgot,” or “will be remember’d for a very long time,” manifesting a certain (and ultimately, somehow, warranted) confidence about the afterlife of his verse itself. But in poems like “The Pennsylvania Disaster,” McGonagall also tends to fixate on more particular, character-driven vignettes—a husband and wife lifting a dead child from a burning cradle, an orphaned “beautiful girl, the belle of Johnstown” staring into the torrent of water in which her parents had just drowned, a heroic telegraph operator wiring messages until the bitter end—that often derive from contemporary accounts.

For that reason, Watson and other critics have contended that McGonagall’s poetry might be considered a kind of nineteenth-century news broadcast. It’s a neat way of making sense of these poems’ strangeness—their fixation on specificity of number, time, and place might be McGonagall’s way of incorporating or transforming the generic markers of “news” into literature. His plodding couplets constitute a kind of doleful formal grid onto which any instance of horror can easily be installed, not unlike the strictures of an Associated Press dispatch or evening news segment. But I found myself wondering if his disaster poetry might be less a dramatization of the news than a staging of its consumption.

The most recognizable elements of his poems—the banal repetitiveness (both across individual works and within them), the recourse to platitude and bromide, the obsession with quantification and particularity—it all bears the contemporary hallmarks of the experience of news. Prior to this year, it was most familiar with regard to mass shootings—the obsessive tracking of the escalating death count; the offerings of hackneyed “thoughts and prayers,” followed by the complaints that have become their own benumbing clichés; the avowals that it will never happen again, supplemented by reassurances that it will be “remembered for a very long time.” Any disaster, in this way, is both devastatingly unique and inevitably iterative.

This year we’ve been introduced to the same phenomenon on a far more deadly scale than McGonagall’s most ghastly memorials could have accounted for. But the plot of this infectious disaster still follows the standard arc of his poems, drifting inexorably from particularity toward abstraction and thus detachment, as the Covid-19 death toll in the United States reached five, then six figures. In this sense, McGonagall’s poetry feels eerily familiar, not unlike reading a versified front page of the New York Times. All that’s left to do is count the dead, mourn predictably, and await the next catastrophe, until the dimly recalled horrors of Covid-19 feel as distant as the litany of nineteenth-century disasters toward which McGonagall’s poetry endlessly gravitated.

The final years of McGonagall’s life, like his poems’ metrical schemas, were a set of frustrated expectations. He had thus far managed to eke out a piddling living through his live performances and the pecuniary kindness of certain acquaintances, but by the end of the nineteenth century he had been banned from most public performances in Dundee. Imposters sent imitations of his work to the local newspapers, one of his sons was accused of breaking the ribs of a local ropemaker, and another was placed in an asylum. The aging poet could hardly leave his home without being ridiculed on the streets with a vehemence that verged on assault. More or less destitute, he took on a few commercial jobs, producing verses in celebration of Sunlight soap and Beecham’s Pills, a laxative.1 When McGonagall died of a brain hemorrhage in 1902, his death certificate misspelled his name.

McGonagall faded from the public’s imagination for several decades, but the inevitable cult gradually began to coalesce. Appreciation societies were formed, plaques were erected, Dundee and Edinburgh squabbled over who deserved to claim McGonagall as a native son. A 1974 film, The Great McGonagall, starred one of the poet’s biggest boosters, the comedian Spike Milligan, in the title role. (It was a flop, and featured an incongruous nude scene inserted at the insistence of the film’s producer, a noted pornographer.) More recently, J.K. Rowling’s Professor Minerva McGonagall was named for the poet, the belabored joke being the apparent vast intellectual gulf between the clueless William and Greek mythology’s sage Minerva.

One school of thought still wonders whether or not McGonagall was the genuine rube that he often seems; whether there was a subtle careerism at play, even a knowing hucksterism; and whether he might have been perfectly willing to play to his audience’s expectations for a meager income in desperate times. It’s a theory that could partly explain his fixation on national tragedy: What better way to elevate himself above his provincial status than to garner notice by casting himself as national bard? As poetic town crier on a countrywide scale?

This is likely an irresolvable question, and any honest account of McGonagall’s career has to settle somewhere in between these two poles—assuming that the poet was aware of the joke if never entirely in on it (by the end of his life, McGonagall’s card identified himself as both a poet and a comedian). But to regard him chiefly as a fool, to laugh at him from a comfortable historical distance, is to ignore the ways in which his disaster poetry, in all its maladroit amateurism, can make contemporary readers uncomfortable, sensitive to the distance, even the callousness, with which the unimaginable must be confronted.

McGonagall’s poems seem to mark the point at which language fails to adequately respond to a kind of loss that is, perhaps literally, unimaginable. Its desperate recourse is the jumbled McGonagallisms for which the poet is known but with which we’re all familiar as a way of processing tragedy. There’s something funny about “The Tay Bridge Disaster,” to be sure, but I wonder whether its critics have missed the mark about the nature of its comedy. I wonder, especially now, whether it isn’t nervous laughter after all.

1 In addition to curing constipation, wrote McGonagall, “They are admitted to be worth a guinea a box / For bilious and nervous disorders, also smallpox, / And dizziness and drowsiness, also cold chills, And for such diseases nothing else can equal Beecham’s Pills.” ↩

Matthew Sherrill is a senior editor at Harper’s Magazine.

'文學, 語學' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Love and Desolation: Remembering Eileen Chang(張愛玲) (0) | 2020.09.30 |

|---|---|

| How Chekhov invented the modern short story (0) | 2020.08.28 |

| Stuck with Ezra Pound (0) | 2020.08.14 |

| Dickens in Brooklyn (0) | 2020.08.06 |

| An Elegy for the Landline in Literature (0) | 2020.07.28 |