Russian ear market

The New Criterion, January 2022

Gorbachev in 1985 at a summit in Geneva, Switzerland

When the kgb chief Yuri Andropov became the Soviet leader in 1982, candidates for office besieged him. Whenever someone began, “Let me tell you about myself,” Andropov replied: “What makes you think you know more about yourself than I know about you?”

The totalitarian Soviet Union, which kept such a close eye on its citizens, seemed stable, but it collapsed with incredible speed. Almost no one expected that, by the end of 1991, the Soviet Union would no longer exist and that fifteen squabbling republics would take its place. Why did this happen? This is the puzzle that Vladislav Zubok, once a researcher for the Soviet expert Strobe Talbott, sets out to explain in Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union.1

Nassim Nicholas Taleb famously described a “black swan” as a highly unlikely event that, after it happens, falsely seems as if it had been inevitable. Analysts who did not anticipate the end of the Soviet Union described it in retrospect as bound to happen. In fact, as Zubok demonstrates, the course of events ending in the country’s disintegration was anything but inevitable. Only a “hard-core determinist” who disregards the evidence, he asserts, could examine the details of what happened and conclude that no other outcome was possible. There were many turning points, and choices made a difference, as did accidents like Chernobyl. The result also depended crucially on the personalities of the leaders, especially the Communist Party leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

The totalitarian Soviet Union, which kept such a close eye on its citizens, seemed stable, but it collapsed with incredible

Andropov knew that the Soviet economy was in terrible shape. Since producers were evaluated on gross output, quality suffered, and since one factory’s output was another’s input, that quality worsened at each step in the production process. Poor-quality steel led to poor-quality nails which were used in buildings that readily collapsed. Televisions and other appliances were so poorly made that even Soviet citizens would not buy them. If one valued goods according to the market, as Western economists do, then these goods were worthless. Yet they consumed resources. Year after year, central planners mandated more production. Warehouses were built to contain ever-increasing piles of unsellable goods. For similar reasons, food was produced that rotted before it reached consumers. The only part of the economy that worked was the military-industrial complex.

Because Andropov died a mere fifteen months after assuming power, reform was left to his protégé, Mikhail Gorbachev, who, after the thirteen-month rule of the geriatric Konstantin Chernenko, took over in 1985. Although Andropov and Gorbachev both recognized the need for change, they differed in approach. Andropov represented the classical conservative reformer: step-by-step experiment, using trial, error, and correction to prepare for the next step. The all-powerful Communist Party, backed by the kgb, would implement the changes.

Given the severity of the country’s economic crisis, was such a slow approach feasible? Could a party filled with people brought up to think in terms of central planning, to prefer command to incentives, and to assume that consumers should be grateful for anything, actually make the economy more efficient? Could the secret police, who had mastered violence and intimidation, adopt a whole new mentality of innovation and risk-taking?

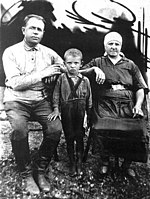

Gorbachev and his Ukrainian maternal grandparents, late 1930s

Unlike his mentor, Gorbachev answered these questions in the negative. He viewed the party as an obstacle. Rather than proceed step by cautious step, he pushed full speed ahead to implement change both extensive and irreversible. But he had no idea what he was doing. To remake an economy, it pays to know economic theory at a reasonably sophisticated level, but Gorbachev still thought in terms of Marxism-Leninism. He had little conception of what a “market” was. When I began my career in Slavist studies, scholars debated whether anybody still believed in Marxist-Leninism, but there is no question that Gorbachev idolized Lenin and blamed only Stalin for the country’s woes. So he kept looking in Lenin’s works for clues about what to do. Zubok makes this superstitious devotion to Lenin’s writings seem like a form of bibliomancy.

Lenin first tried to abolish all trade outside government control, to militarize labor so that absence from work would be treated as desertion, and to eliminate money. Peasants would not be paid for their grain, they would yield it at gunpoint. When they revolted, Lenin demanded they be suppressed with the greatest cruelty possible. In one case, poison gas was used. The predictable result was unprecedented mass famine, and so Lenin eventually retreated to the “New Economic Policy,” a return to the market meant to be as short as possible. Gorbachev took that return as his inspiration. Lenin had plunged headlong into radical reforms, so Gorbachev resolved to do the same.

As a Leninist, Gorbachev never quite reconciled himself to private property and kept seeking some middle way. The result, in 1987, was the oxymoronic “Law on Socialist Enterprises” designed to combine socialism with a (state-regulated) market. Each enterprise would henceforth belong to its management and “workers’ collective.” The “Three S’s” policy—self-accounting, self-financing, and self-governance—formed the basis of decision-making. For the first time, party bosses would not interfere. Enterprises also acquired freedom of export and could have their own currency accounts. In practice, they used their newfound freedom not for investment and innovation but to cannibalize their capital and send it abroad.

The Soviet Union had already acquired a mountain of debt, as had its satellites in Eastern Europe. At some point, lenders wonder whether they can ever be repaid, and they either dramatically raise interest rates—which makes repayment even harder—or refuse to lend any more. Instead of improving the dire situation, Gorbachev’s economic reforms made it worse. Tax receipts declined by more than half. Even old economic partners like Deutsche Bank and the Austrian banks, Zubok explains, closed off Soviet access to money markets. Would the country even be able to import needed food?

Far from providing their Russian rulers with wealth, the Eastern European countries required subsidies, as did Mongolia and Cuba. The infusion of rubles into the Soviet economy rose from under four billion in 1986 to over ninety-three billion in 1991.

Zubok compares Gorbachev to the sorcerer’s apprentice, who could not control what he had unleashed. Highly reluctant to use force, Gorbachev projected an image of weakness that the three Baltic republics—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—took as an opportunity to gain independence. Zubok repeats that if Gorbachev had been willing to use force, as the Chinese did in Tiananmen Square, and was less given to waffling, he could have held the country together long enough for some sort of reforms to work. Historians often assume that personalities don’t matter in comparison with underlying social forces, but Zubok maintains that “Gorbachev’s leadership, character, and beliefs constituted a major factor in the Soviet Union’s self-destruction” because “he combined ideological reformist zeal with political timidity, schematic messianism with practical detachment.”

The freedom to travel abroad that accompanied the economic reforms changed everything.

The freedom to travel abroad that accompanied the economic reforms changed everything. For the first time, many Soviet citizens could visit the West, and what they saw there dumbfounded them. For people accustomed to perpetually empty shelves and long lines, the sight of an ordinary Western supermarket, packed with choices and free of lines, proved almost unbelievable. On a trip to the West, these sights converted Yeltsin (when sober) from a socialist to a believer in markets.

With Gorbachev as the head of the Soviet Union, Yeltsin found a power base in the Russian republic (officially the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, or rsfsr). He therefore had every incentive to weaken the union and transfer power to the other republics. Instead of seeing Russia as the ruling part of the empire, he treated it as another victim of Soviet imperialism. It was as if not only Scotland wanted to secede from the United Kingdom, but England as well, while claiming Britain’s resources, army, and police for itself. Bit by bit, the Soviet Union lost out and eventually disappeared. Zubok describes Yeltsin as an alcoholic, sadistic bully who believed in democracy but loved to dictate. An economic reformer, he had no knowledge of economics and did not understand the radical reforms he demanded.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s book Rebuilding Russia impressed Yeltsin. Although Westerners who cannot get beyond ready-made categories have denounced Solzhenitsyn as a Russian chauvinist and imperialist, he was almost the opposite: a patriot who opposed all imperial ventures. In Solzhenitsyn’s view, Russia should have stopped controlling its neighbors and focused on its own spiritual renewal. It needed to recover a sense of morality after decades of Communist teaching that compassion and conscience are reactionary concepts. Further, he believed that the empire weakened Russia, which should consequently get rid of it.

Solzhenitsyn impressed Yeltsin with the idea that Russia should confine itself to the lands where the population is primarily Russian or, at least, Slavic. That meant letting the Baltic, Transcaucasian, and central Asian republics go their own way. Since the Soviets had set republican boundaries for arbitrary, political reasons, Solzhenitsyn saw no reason those boundaries should be respected. They should, rather, be redrawn to reflect the identity and desires of each region’s people. The new Russia would therefore include predominantly Russian areas of neighboring republics.

Yeltsin soon discovered that republics demanding the right to separate would not consider giving the same right to their own provinces. Reading Zubok’s account, I was struck by the fact that Crimea, which President Putin invaded in 2014, already posed an issue as the ussr was falling apart. With a population overwhelmingly Russian, it had been ceded to Ukraine by the Communist Party leader Nikita Khrushchev in 1954. The Donbass, the predominantly Russian area of Eastern Ukraine that is now the scene of armed conflict, also posed an issue as the country was breaking up. Would Ukraine have been better off had it not insisted on retaining these undigestible parts?

With Gorbachev trying to hold the ussr together in some form and Yeltsin siding with the republics wanting independence, their rivalry dominated the news. Zubok relates the story of how Richard Nixon, on a visit to the ussr in 1991, could not get an appointment with either Yeltsin or Gorbachev. Nixon’s advisor Dimitri Simes tried a ruse. Knowing the kgb was monitoring them, Nixon and Simes began to talk loudly in their hotel lobby about their upcoming meeting with Yeltsin. Within a few hours, Gorbachev invited Nixon for a chat, and an invitation from Yeltsin soon followed.

Even those familiar with the opulence in which the leaders of the world’s first socialist state lived will be shocked by Zubok’s description of the vacation villa Gorbachev had built in 1988. It cost one billion rubles at a time when the Soviet defense budget, which Zubok believes was fifteen per cent of gdp, was seventy-seven billion rubles. Today, the U.S. defense budget is about $750 billion, which would make the cost of an equivalent villa $9.75 billion. That doesn’t include the upkeep and endless staff, such as the scuba divers making sure no one could infiltrate by water. Given the country’s fiscal crisis, one can’t help but recall the extravagance of Louis XVI. As it happened, Gorbachev’s new Congress of People’s Deputies convened in 1989, just two hundred years after the Estates General, which, of course, also resulted from an inability to obtain more credit.

Had Gorbachev been the only incompetent waffler, the ussr might still be here.

Had Gorbachev been the only incompetent waffler, the ussr might still be here. Everyone resembled the Keystone Cops. In 1991 several Soviet leaders staged a coup against Gorbachev with the hope of preserving the union. So incompetent were they that they did not bother to turn off Yeltsin’s phone or prevent him from organizing opposition. One of Yeltsin’s supporters was able to fly to Paris, denounce the coup, and prepare, if necessary, to set up a government in exile. Opposition news sources, who knew what was happening better than the coup leaders themselves, continued their broadcasts to the West. “The situation was unbelievable,” one kgb general recalled. kgb analysts were learning about a crisis “in the capital of our Motherland from American sources.” When Margaret Thatcher accepted advice to telephone Yeltsin, she recalled, “to my astonishment I was put through.”

It was a Keystone coup. Right after the organizing meeting of the plotters’ Emergency Committee, Zubok explains, “some members went home and succumbed to various illnesses. [Valery] Boldin was already suffering from high blood pressure; he went to a hospital. [Valentin] Pavlov . . . tried to control his emotions and stress with a disastrous mixture of sedatives and alcohol. At daybreak, his bodyguard summoned medical help, as Pavlov was incapable of functioning.” Pavlov later took some more medicine to control his nerves and “had a second breakdown that incapacitated him for days.”

To be sure, some on the other side displayed similar ineptitude. “The mayor of Moscow, Gavriil Popov, who had just returned from vacation, huddled in a fortified basement of the [parliament] building, fearful for his life and totally drunk.” Alcohol figures in Russian history as nowhere else.

The coup might still have succeeded if the military had been willing to use force, as their Chinese counterparts had done. “[General Dmitri] Yazov found himself in an awkward situation: he had brought massive military force onto the streets of downtown Moscow, yet he did not want to use it.” The kgb chief Vladimir Kryuchkov proved no braver. He “was well aware of the requirements for a successful coup, but he simply lacked the guts to implement them.”

For Zubok, this indecisiveness marked a turning point. “Had the kgb chief been a resolute counter-revolutionary, history would have turned out differently.” I agree that the collapse of the Soviet Union was not inevitable, but this counterfactual fails to convince. Let us imagine that the coup plotters had retained power: as Zubok himself points out, the junta leaders “had launched emergency rule without any clear plan or a viable economic program.” How would tanks on the streets have refinanced the debit or reduced the deficit? How could these incompetents have managed the secession of the republics? It is hard to see how their rule would have made much difference.

Using remarkably copious archival sources, which he has mastered with impressive thoroughness, Zubok presents an almost day-by-day, or even hour-by-hour, account of events, with what he calls “many ‘fly on the wall’ episodes. . . . To make the texture of the historical narrative authentic, I give preference to instantaneous reactions, rumors and fears, rare moments of optimism and frequent moments of despair, that characterized those times.” It is not a technique for any but the most skilled writers to attempt. When Solzhenitsyn used such a fine-grained approach in his multi-volume novel about March 1917, he was able to convey the sense of events confusing to participants who did not know their outcome. With Zubok it is the reader who is confused. Anyone but a specialist on the fall of the ussr will not only lose the forest for the trees, but also the trees for the branches, even the branches for the twigs.

Since Zubok stresses the economic explanation for events, it is unfortunate that his economic commentaries sometimes lack clarity. On January 22, 1991, Pavlov announced that fifty- and hundred-ruble notes would no longer be valid and had to be exchanged within three days for new ones. Apparently, this forced exchange was supposed to soak up “30 billion rubles from the shadow entrepreneurs and currency speculators,” but Zubok does not explain how exchanging old notes for new ones would soak up anything, or why, if one is transitioning to a market economy, one would want to stifle entrepreneurship destined to be legal. Americans will look in vain for explanations that allow them to use basic economic theory, as taught in college economics classes, to comprehend what was happening.

Zubok accepts the myth, so flattering to some intellectuals, that “for almost two centuries, the intelligentsia had daydreamed about a constitution and people’s rights.” But beginning in the 1860s, the intelligentsia overwhelmingly rejected liberal constitutional reforms and individual rights in favor of one or another revolutionary program, like the intolerant one that eventually triumphed. Indeed, the strict sense of the very word “intelligentsia,” which we get from Russian, designated not educated people but extreme believers in a materialist, atheist, and revolutionary ideology hostile to all moderate change. A truly liberal movement had developed by the early twentieth century, but then even the Kadet (Constitutional Democratic) Party supported terrorism and tried to sabotage the fledgling Duma in order to maintain their credentials as true intelligents (members of the intelligentsia).

By Zubok’s own account, Yeltsin could not wait to get his own kgb and rule by decree.

Zubok’s logic occasionally puzzles. He argues that President Reagan’s increased defense spending, meant to pressure Soviet leaders to make changes, “did not push the Soviet leadership towards reforms: the realization of their necessity dated to the early 1960s.” But the fact that the necessity of reforms had been appreciated for decades does not contradict the possibility that Reagan’s policies “pushed” the leadership into actually embarking on them. Quite the contrary, they could only have been pushed to do what they already had in mind. Zubok also hopes that his book has put paid to the idea that Russia, steeped in despotism, was bound to choose authoritarianism over democracy. Yet the portrait of bungling “democrats” who did not understand democracy makes that view plausible. By Zubok’s own account, Yeltsin could not wait to get his own kgb and rule by decree.

These cavils aside, Zubok’s study presents a powerful, detailed picture of puzzling events of great importance. He wisely concludes: “This amazing story teaches us not to trust in the seeming certainty of continuity and should help us prepare for sudden shocks in the future.” One is bound to reflect: a long history does not guarantee stability or even continued existence. A country that acts as if debts can grow without limit, is led by a bumbling chief executive whose weakness is obvious to foreign enemies, and contains culturally different regions increasingly contemptuous of each other—and whose intellectual leadership no longer believes in its founding principles—such a country may experience a sudden catastrophe resembling the disappearance of the ussr.

Gary Saul Morson, the Lawrence B. Dumas Professor of the Arts and Humanities at Northwestern University, co-authored, with Morton Schapiro, Cents and Sensibility (Princeton).

This article originally appeared in The New Criterion, Volume 40 Number 5, on page 86

Copyright © 2022 The New Criterion | www.newcriterion.com

https://newcriterion.com/issues/2022/1/russian-bear-market

'러시아' 카테고리의 다른 글

| In Photos: St. Petersburg Grapples With Ice-Covered Streets (0) | 2022.01.22 |

|---|---|

| Sanctions on Putin Would be Step Too Far, Kremlin Warns U.S. (0) | 2022.01.13 |

| Why Russia Fears a Ukrainian Offensive (0) | 2022.01.09 |

| Three Decades After Soviet Collapse, Life in Russia Could Be Worse (0) | 2022.01.01 |

| Revisiting the Red Century (0) | 2021.12.20 |