The Art Movement That Embraced the Monstrous

Since its formation in the 1920s, surrealism has produced works that are unnerving, disturbing—and perversely appealing as well.

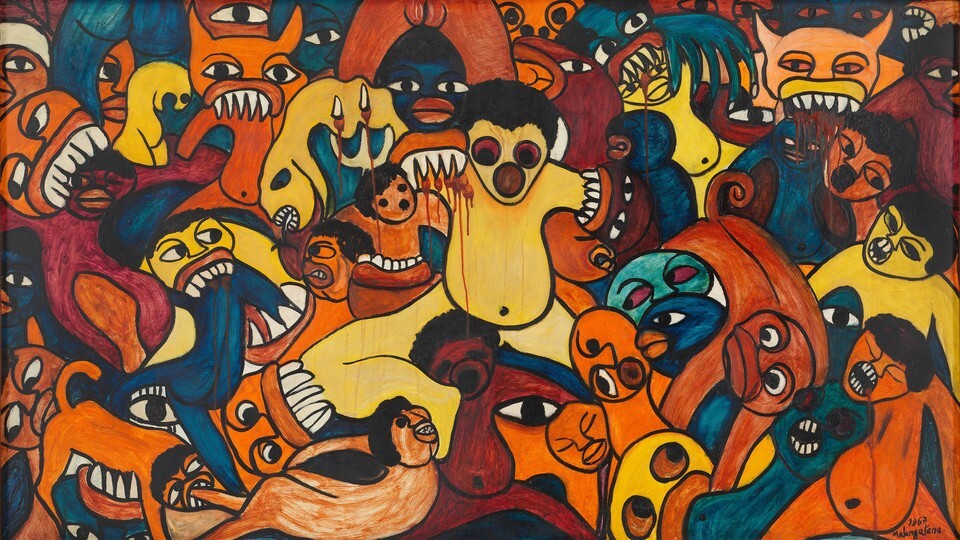

An untitled work by Malangatana Ngwenya, 1967 (Tate)

By Sophie Madeline Dess

The Atlantic, January 10, 2022

To be on the internet today is to confront unsettling images—of war, climate change, humanitarian crises. Weird visuals crop up too. A YouTube algorithm provides me, for instance, with videos of a pimple-popping bonanza, or a series of videos in which young men eat glue. If disquieting sensory experiences abound in daily life, why go and seek more out? That question might be put to visitors of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Surrealism Beyond Borders” exhibition, a show filled with grotesque representations of political upheaval and private horror, but also with thrillingly odd and beautiful demonstrations of imagination.

The Met’s exhibition aims to show a nonchronological and nongeographical view of surrealism, which became a transnational aesthetic phenomenon after being formally established in Paris in 1924 and spreading globally throughout the 20th century. Its founder, André Breton, defined surrealism as pure “psychic automatism”—in which the whims of the artist’s unconscious direct their art making. Artists deployed surrealist techniques to process demons, both internal and external, but also to challenge conventional thinking (is a pipe really a pipe, as René Magritte famously queried?) and to express fantasies of artistic or political liberation. The Freudian-influenced idea was that by unlocking the unconscious, artists could assert the independence of their and their viewers’ interior worlds. Radical nonconformism was a central tenet, which led some artists to use the form to challenge the pressures and constraints of oppressive regimes.

The Mozambican artist Malangatana Ngwenya (known professionally as Malangatana) adapted surrealist tradition in this very way. Through the ’60s, as Malangatana participated in Mozambique’s protracted war for independence from Portugal, the surrealist touch was vital—it allowed his images to be legibly brutal without being (perhaps incriminatingly) specific. At the Met, an untitled work from 1967 features a compressed pack of bright and feral, phantasmagoric beasts. The center figure is being eaten alive, blood dripping down his chest, his eyes wide in horror. Sounds of a feeding frenzy seem to buzz forth. The figures appear to be in a hellish prisonscape—fitting, as Malangatana himself was arrested only four years prior for revolutionary activities.

Like all good art, though, the image is broad in implication. It could suggest the exploitative ferocity of the Portuguese colonizers, ruthlessly thirsting for power, or the psychological state of Mozambicans, who were pushed into war with their oppressors (as Malangatana shared in a 2007 interview, during the fight for independence, Mozambicans had no way out). The varied readings of these wild figures add to the work’s surreality. The pain in the painting transcends the specifics of its time and place. It rises to the level of archetype, representing a broader spectrum of violence and unease. If one feels an uncanny kinship with these demons, that is the exact kind of pact surrealism allows.

The form, however, can charm even as it unnerves, as is the case in the Puerto Rican artist Frances del Valle’s Guerrero y Esfinge (“Warrior and Sphinx”), on view near the Malangatana. Del Valle’s 1957 painting makes me laugh. In it, a huge, sphinxy figure kneels not just a little sexually on what appears to be a postapocalyptic Egyptian vista. The sphinx puppets a crouched, contorted warrior who has, apparently, just been made to pulverize his own head. The image is baffling, oddly divine. Its shapes are compellingly fluid. The massive sphinx looks both fetal and futuristic, and the warrior’s ravaged head—a cluster of bright pink—resembles a knotted placenta. But the horrific is made gentle through del Valle’s thick, luminescent paint. Pearly limbs recall unicorns, fairies. The softness of these textures, paired with the tyrannical posture of the sphinx, turns the painting into a cryptic yet alluring riddle. Del Valle reveals the perverse appeal in confronting the confounding.

Perhaps the most perplexing and amusing image in surrealism is Magritte’s 1934 painting Le Viol (“The Rape”), housed permanently in Houston’s Menil Collection. Like Malagatana’s Untitled, it has the power to disturb, and yet, like del Valle’s work, it evokes a strange sense of mirth as well. Le Viol is a figurative portrait of sorts—except with bare breasts in place of eyes, a belly button in place of a nose, and a frothily haired crotch where the mouth would be. Rendered in Magritte’s careful hand, these parts become so expressive that the nipples seem to squint, the belly button seems to breathe, the sex seems to smile. If a viewer laughs, they laugh not just at the sudden liveliness of these features. Instead, they may also be responding to a dissonant synthesis: the absurdity of the image paired with the declarative violence of the title, and the utter seriousness of the painting method. In Le Viol, each brushstroke is made with painstaking deliberation, resulting in a weighty stillness that calls to mind the Mona Lisa.

Read: How surrealism enriches storytelling about women

That one can laugh while viewing this sort of work is key to surrealism’s machinations—getting us to do and feel things we did not know we could do or feel. The experience provokes questions: If nipples, too, can suddenly blink, see, judge, emote—if all parts of the body teeter on the edge of animacy—what are we really doing when we touch them? How much more violent is every violation?

Magritte freely exploited surrealism’s ability to distress. “A picture that is really alive should make the spectator feel ill,” he once told his art dealer. Indeed, at the Met’s show, that sustained viewing of biomorphic forms and cluttered limbs can unsettle a person. And though many art historians consider surrealism to have ended—often citing different dates in the latter half of the 20th century—its legacy, or at the very least the discomfort it inspires, continues to evolve.

Prior to the Met’s show, my most recent of these disquieting experiences involved, coincidentally, another encounter with breasts-and-eyes imagery. This past April, at Sotheby's New York location, I turned a corner and came across the Kenyan-born American artist Wangechi Mutu’s Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumors (2005). The work consists of 12 surrealist-inspired collages in which anatomical diagrams are layered with images from fashion spreads, pages from African-art books, and pictures yanked from National Geographic, forming distorted female faces. In one instance, blubbery breasts spill out from drooping eyes; in another, a bent knee becomes a fleshy nose; in yet another, a vagina smothers the top third of a woman’s face, and her mascaraed eyes blink like indented cysts. In other words, visual mayhem.

Mutu’s use of layered imagery echoes the barrage-like experience of the digital world. Everything in the collages seems to be happening at once. To process the work, one must slow down and decode each face, treat every cut-out bit with suspicion. The result, paradoxically, is that the collages appear startlingly clear. In one instance, what appears to be an upside-down fennec fox sits between the nose and upper lip of one of Mutu’s women: Never have I approached an animal with a fiercer sense of interrogation. The artist seemingly pressed pause on my rapid-fire visual intake, showing me the constituent parts both individually and as a devotedly curated whole.

Read: Lorna Simpson maps the complex galaxies of Black women’s hair

Mutu is not alone among contemporary artists in keeping the surrealist vein flowing. The American artist Juliana Huxtable, for example, poses as a sexualized shitting cow in Cow 1 (2019). The coy pose slightly recalls del Valle’s sphinx, as do the chalky pink-and-technicolor-unicorn vibes. Here the face of the cow is the artist’s own. As she defecates, she makes a face not of embarrassment but of exhausted sexual invitation. Huxtable mimes the self-fashioning that is bred on social media. Hers, however, is at once more knowing, and more self-deprecatory. Similarly, in Appetizer (2017), the French painter Julie Curtiss lays a severed (and immaculately manicured) finger over sushi rice in a macabre distortion of shrimp tempura. As in Huxtable’s work, the curated body is repackaged and hyperaware. The slashed-finger sushi asks, Don’t I look tasty? And the answer is, weirdly, Yes, you kind of do.

In the 21st century, surrealism might no longer be the art world’s reigning movement, but it is uniquely positioned to slow down the absorption of what we’d otherwise find familiar. In twisting everyday imagery into the monstrous, or simply infusing it with quirk, surrealism offers a new clarity of vision. These artworks demand that we actively process what we see; that we stop gazing at images and start interrogating them. If today’s surrealism makes us feel a little ill, we know that it is working.

'藝術' 카테고리의 다른 글

| How Nudity Both Reveals and Conceals (0) | 2022.02.18 |

|---|---|

| What Will the “Metaverse” Do to Art and Culture? (0) | 2022.01.26 |

| If You Frame It Like That (0) | 2021.05.31 |

| Obscura No More (0) | 2021.05.05 |

| The Swirl of History (0) | 2021.04.22 |