Working as a novelist can be a truly discouraging occupation. On my bad days, I look at my bookshelf and see nothing but how fierce the competition is. As a footballer, or a chef, or a neurosurgeon, at least you only compete with those of your profession who are still alive. Shockingly, as a novelist, your fiercest competitors are dead people. And there are quite a few of those.

On my good days, however, I look at my bookshelf, pick up a book, and start reading, delighted with what great stories humans have been telling for millennia, and all the things that I can learn from them, even when they’ve been dead for more than 2,000 years.

One such book that I regularly pick off my shelf to rejoice in is Herodotus’ Histories. Alex Talbot, writing for Antigone, calls Herodotus “that curious world traveler,” an “entertainer” who “loved flinging out fireworks of wonders from his faraway travels left and right to explode his audience’s minds.” I can only agree with Alex: The liveliness of Herodotus’ accounts, his willingness to admit that he may be wrong, and his curiosity about the world are the ingredients that make his enquiries (for that is what his “Histories” are) such a great pleasure to read, even some 2,500 years after they were written.

Or perhaps especially 2,500 years after they were written: As one of his translators, Tom Holland, points out, “Herodotus understood… that he was living in a globalized era.” So are we, of course, if perhaps we are globalized in a different way. This may be why my favourite episodes in Herodotus’ Histories are those where he speaks of far-away lands and peoples, in particular the cosmopolitan, constantly travelling Scythians.

The word “Scythian” is in fact used by the Ancient Greeks as an umbrella term for a diverse number of nomadic and semi-nomadic horse-archer communities sharing a common cultural spectrum. They lived in the first millennium BC on the eastern fringes of the world known to the Greeks, and have been occasional visitors to the pages of Antigone. Back in Antiquity, these horse-archers could be found moving through and living on lands that stretched from the Himalaya and Altai mountains in modern-day China to the Black Sea in modern Georgia. From there, it isn’t too far a ride to the Greek cities of Asia minor (modern Turkey), such as Halicarnassus (where Herodotus was born), Smyrna (which may have been the birthplace of Homer: a controversial topic!), or the non-Greek Wilusa (better known to us as Troy). From the 8th century onwards, they appeared in important Greek accounts. As Barry Cunliffe has written, “Stories of strange people who lived in the lands of mists on the north shores of the [Black] sea were circulating in the eighth-century Greek world and were known to both Hesiod and Homer.”[1]The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe (Oxford UP, 2019) 30.

Herodotus displays great accuracy in his descriptions of Scythian customs, burial rites and material culture, much of his accounts having been widely confirmed by modern-day archaeologists. Quite aside from their accuracy, they are also immense fun. My all-time favourite episode concerns my most beloved group of characters in Herodotus who operate among the Scythians: the Pirate Amazons.

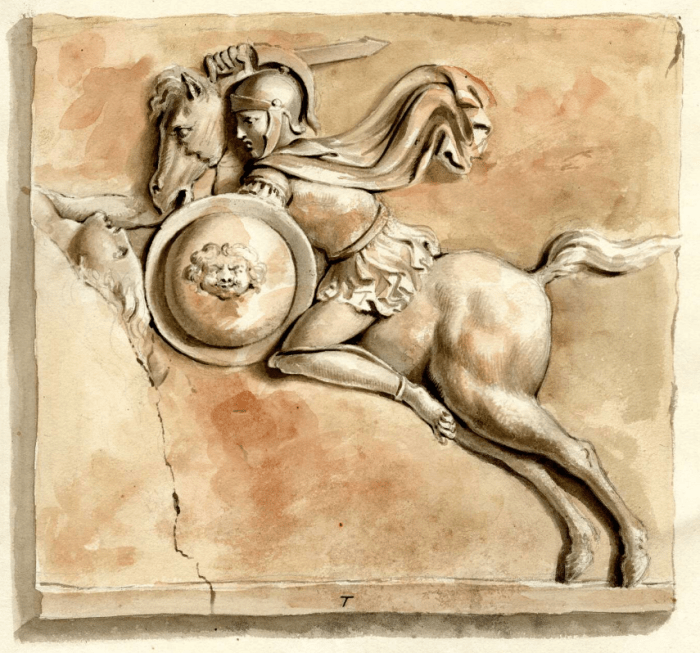

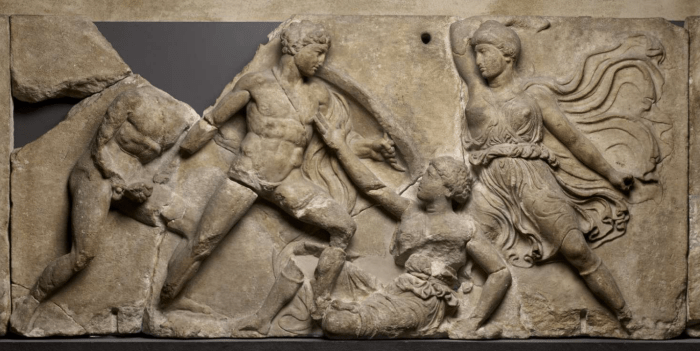

The episode was first brought to my attention by Adrienne Mayor in her study of Scythian warrior women, whom she identifies as the historical counterparts of the mythical Amazons, legendary female warriors in Ancient Greece. In Book 4 of his Histories, Herodotus tells us of something that happened during “the war between the Greeks and the Amazons”: after the Greeks, led by the mythical hero Heracles, won a battle against the Amazons at the mouth of the river Thermodon, they sailed away in three ships, taking the surviving Amazons with them to serve as their slaves.

However, the Amazon women didn’t much feel like living a life of slavery and concubinage. While the ships were out at sea, they started a mutiny. Rising up against their Greeks captors, they “hacked them down” (4.110) and took control of the ships. Unfortunately, there was one thing the Amazons had not considered: only after they’d killed all their captors did it occur to them that they had no idea how to steer a ship. They were horse-archers, not sailors.

There they were, stranded out on the Black sea, imprisoned on a ship that they had no clue how to control. They were, in Herodotus’ words, at the “mercy of the waves and the wind” (4.110).[2]This passage, and all of the others cited in this article, can be freely read in English and Greek via the Perseus Project here.

Now, you might remember what happened when another fleet of ships in Greek myth found itself at the mercy of the waves, winds, and weather gods. When the Greek warrior Odysseus tried to return home to Ithaca after the Trojan war, the sea gods made sure it took him ten years to reach the safety of his home, in spite of his mastery of the art of sailing.

Interestingly, the gods and elements who chose to be so disruptive to Odysseus decided they would be much kinder to the Amazon women aboard their captors’ ships: wind and waves brought them directly to a friendly coast, bordering Lake Maeëtis in “the Land of the Free Scythians”. Even more than that: “The first thing they came across was a herd of horses, which they promptly seized, saddled up and used to plunder all they could from the Scythians.”

At this stage, surely, it would be time for Herodotus to punish these women, who kill Greek slavers, then steal horses and food from Scythian men? If this were Greek myth, I suspect that all of them would at this point be turned into lionesses, or reeds, or perhaps some animal that Zeus could have his way with without his wife noticing.

Not in Herodotus, though. Instead, he tells us how some of the Scythian men react to the appearance of these Pirate Amazons. Quite unexpectedly, they decide to offer themselves up as willing sexual partners. These young men took one look at the Amazons and apparently decided that here were the future mothers of their children.

The Amazons turned out to be very enthusiastic about this idea, telling all of their friends about it, and coming back for more on a daily basis. Quite soon, the two camps merged into one, and the Scythian men suggested they should marry the Amazon women, return them to their settlements and have children together: “we have parents, and we have our own belongings” (4.114).

Pirate Amazons, living as Scythian housewives? “We would never be able to settle down with your women… We shoot arrows, throw javelins, ride horses. But what do your women do?” (4.114) The women made an alternative suggestion: “If you really want us as your wives, and to be seen to behave with complete honour as well, go to your parents and take the due share of your possessions. Then, on your return, we can go and set up a home together of our own” (4.114).

The young men agreed, went and got their things, then settled in a new place with their brides, together founding the new tribe of the Sauromatians. And so the Pirate Amazons lived happily ever after, Herodotus tells us. “And from that time to this, the Sauromatian women have kept to their primal way of life: they go out hunting, whether their husband are with them or not, they go to war and they dress exactly like the men” (4.117).

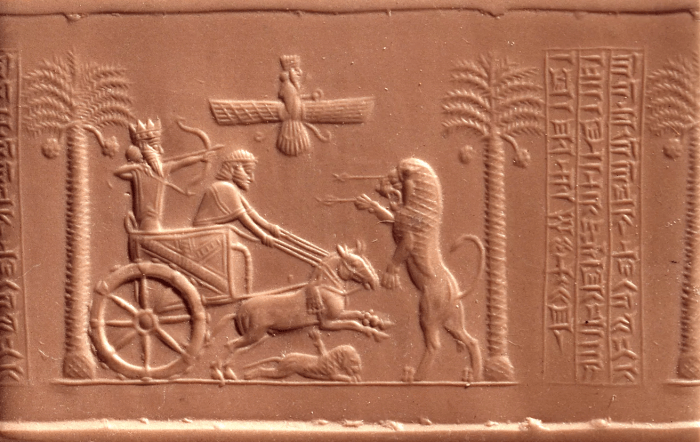

In retelling this episode – and on insisting on the independence and emancipation of Scythian women, which made them so unlike the women of Herodotus’ Ancient Greek homeland – Herodotus displays the central quality that many great storytellers have possessed throughout the ages. He had no fear of what was strange to him but met it with great curiosity and without judgment. He applied the same principle to the Persian King Darius, often thought to be one of the main enemies of the Ancient Greeks.

Where history conventionally turns strangers into enemies, one party into victors and another into losers, Herodotus instead shows strangers to be people: as humane, as clever, as strong, and sometimes even wiser than we are.

Speaking of Darius and the Scythians, I could also tell you about the ingenious way the Scythians engaged the Persian armies of King Darius, winning a war without taking any casualties, and the wonderful letter the Scythian commander wrote to the Persian King.

But that will have to wait for another day – or you may grab a copy of Herodotus’ Histories and look it up yourself.

[3]4.121–42, with the wonderful letter at 126–7. I promise you that you’ll enjoy it. Whether he speaks of Egyptian cats or Scythian warrior women, Herodotus paints a much livelier and more exciting picture of our historical ancestors, women and men, than we are accustomed to. The tendency to think of earlier humans – or those from strange lands, speaking strange languages – as less creative, imaginative, and smart than ourselves still sits deep, as David Wengrow and the late David Graeber have pointed out in their recent study The Dawn of Everything. Reading Herodotus is a wonderful antidote to that. Travelling, seeing the world, meeting strangers has always been fun, whether they live in distant lands or far-flung periods of the past. Writing about them as people, with curiosity, passion, and an open mind, is not only a pleasure, it is our obligation as story-tellers, historians, writers, humans.

Fortunately, Herodotus has left us his Histories to show us how it’s done.

Christine Lehnen is a novelist and researcher at the University of Manchester. She is currently working both critically and creatively on a rewriting of the story of Penthesilea. Her previous essay for Antigone, on Penthesilea, can be read here.

Further Reading

Adrienne Mayor’s The Amazons (Princeton UP, 2014) is the first book to turn to if you are interested in these mythohistorical warrior women; her article for Antigone on Plato’s take on the Amazons can be read here. Further historical context is given by David W. Anthony’s The Horse, the Wheel, And Language (Princeton UP, 2007) and Barry Cunliffe’s The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe (Oxford UP, 2019).

For Herodotus, I recommend Tom Holland’s excellent translation of the Histories (Penguin Classics, London, 2013). His revealing blog post on Darius, Herodotus and the Scythians can be read on the British Museum’s site here.

A brilliant introductory video to Herodotus, animated by Cindy Zeng of McGill University, can be watched here.