Why We Choose to Suffer

In the search for a meaningful life, simply seeking pleasure isn’t enough. We need struggle and sacrifice.

By Paul Bloom

When life is going well, we can forget how vulnerable we are. But reminders are everywhere. There is always the possibility of pain—a sudden ache in the lower back, a cracked shin, the slow emergence of a throbbing headache. Or emotional distress, such as realizing that you just used Reply All to reveal an intimate secret. Such examples only touch the surface. There is seemingly no limit to the misery we can experience, often at the hands of others.

The simplest theory of human nature is that we work as hard as we can to avoid such experiences. We pursue pleasure and comfort; we hope to make it through life unscathed. Suffering and pain are, by their very nature, to be avoided. The tidying guru Marie Kondo became famous by telling people to throw away possessions that don’t “spark joy,” and many would see such purging as excellent life advice in general.

But this theory is incomplete. Under the right circumstances and in the right doses, physical pain and emotional pain, difficulty and failure and loss, are exactly what we are looking for.

A study of mountain climbers found that those who suffered the most were the most positive about their experience. Photo: OLIVIER CHASSIGNOLE/AFP/Getty Images

Think about your own favorite type of negative experience. Maybe you go to movies that make you cry or scream or gag. Or you might listen to sad songs. You might poke at sores, eat spicy foods, immerse yourself in painfully hot baths. Or climb mountains, run marathons, get punched in the face in a gym or dojo. Psychologists have long known that unpleasant dreams are more frequent than pleasant ones, but even when we daydream—when we have control over where to focus our thoughts—we often turn toward the negative.

Some of this is compatible with a sophisticated version of hedonism, one that appreciates that pain is one route to pleasure. The right kind of negative experience can set the stage for greater pleasure later on; it’s a cost we pay for a greater future reward. Pain can distract us from our anxieties and help us transcend the self. Choosing to suffer can serve social goals; it can display how tough we are or serve as a cry for help. Emotions such as anger and sadness can provide certain moral satisfactions. And effort and struggle and difficulty can, in the right contexts, lead to the joys of mastery and flow.

But many of the negative experiences we pursue don’t provide pleasure at all. Consider now a different kind of chosen suffering. People, typically young men, sometimes choose to go to war, and while they don’t wish to be maimed or killed, they are hoping to experience challenge, fear and struggle—to be baptized by fire, to use the clichéd phrase. Some of us choose to have children, and usually we have some sense of how hard it will be. Maybe we even know of all the research showing that, moment by moment, the years with young children can be more stressful than any other time of life. (And those who don’t know this ahead of time will quickly find out.) And yet we rarely regret such choices. More generally, the projects that are most central to our lives involve suffering and sacrifice.

Research shows that raising young children is one of the most stressful parts of life, yet parents seldom regret it. Photo: Getty Images

The importance of suffering is old news. It is part of many religious traditions, including the story in Genesis of how original sin condemned us to a life of struggle. It is central to Buddhist thought—the focus of the Four Noble Truths.

Not all suffering is valuable, though. To tell someone who is deeply depressed that they need more pain in their life would be cruel if it weren’t so ridiculous. I know psychologists who will tell you that bad experiences are good for you—they speak about post-traumatic growth, an increase in kindness and altruism, more meaning in life—and this sometimes does happen. But the evidence suggests that common sense is right here: Unchosen suffering is awful; avoid it if you can.

But chosen suffering is a different story. A life well lived is more than a life of pleasure and happiness. It involves, among other things, meaningful pursuits. And some forms of suffering, involving struggle and difficulty, are essential parts of achieving these higher goals, and for living a complete and fulfilling life.

Some people report more meaning in their lives than others. In a landmark 2013 study in the Journal of Positive Psychology, Roy Baumeister and colleagues asked hundreds of subjects how happy they were and how meaningful their lives were, and then asked other questions about their moods and activities. It turns out that some features of one’s life relate to both happiness and meaning—both are correlated with rich social connections and not being bored. They are also correlated with each other: People who report high levels of happiness tend to say the same about finding meaning in their lives, and vice versa. You can have both.

“The more people report thinking about the future, the more meaning they say they have in their lives—and the less happy they are.”

But there are also differences. Health, feeling good and making money are all related to happiness but have little or no relationship to meaning. Moreover, the more people report thinking about the future, the more meaning they say they have in their lives—and the less happy they are. The same goes for stress and worry—more meaning and less happiness.

All of this suggests that meaning and struggle are intertwined. In another study, done by the software company Payscale, more than 2 million people were asked what they did for a living and how much meaning they have in their lives. It turns out the most meaningful job is being a member of the clergy. Others at the top of the list include teachers, therapists, physicians and social workers. All of these jobs involve considerable difficulty and a lot of personal engagement.

What about day-to-day experiences? In a study published in the Journal of Positive Psychology in 2019, Sean C. Murphy and Brock Bastian asked people to think back on their most significant experiences, to describe each one in a paragraph and to rank them for how meaningful they were. Participants were also asked to indicate the extent to which the experiences were pleasurable or painful. It turned out that the most meaningful events tended to be on the extremes—those that were very pleasant or very painful. These are the ones that matter, that leave a mark.

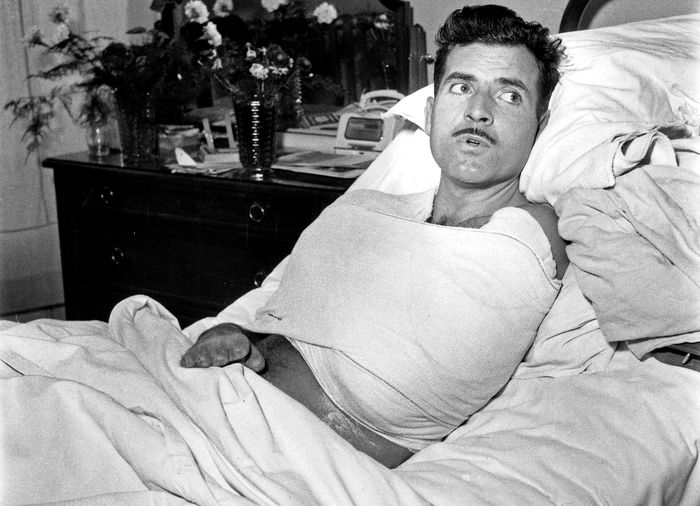

In a discussion of high-risk mountain climbing published in 1999, the economist George Loewenstein notes that some of the people who had suffered the most were the most positive about their experience. Maurice Herzog, who in 1950 was part of the first team to summit Nepal’s Annapurna, lost several fingers and parts of his feet but said that the ordeal “has given me the assurance and serenity of a man who has fulfilled himself. It has given me the rare joy of loving that which I used to despise. A new and splendid life has opened out before me.” Lowenstein dryly concludes, “Meaning-making may also be enhanced by the loss of body parts.”

Mountaineer Maurice Herzog lost several fingers and parts of his feet after climbing Nepal’s Annapurna in 1950. Photo: AGIP/Bridgeman Images

Few of us voluntarily surrender our appendages in the pursuit of a good life, but we often do seek out more minor negative experiences, in part for their transformative effect but also because we might simply want to possess these experiences later. We want to store them in memory and consume them in the future. As the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca put it, “Things that were hard to bear are sweet to remember.” They are part of what we see as a meaningful life.

Not everyone is convinced. Some people, like some of the subjects in the Baumeister study, focus on pleasure and happiness and are less interested in meaning and suffering. Is this really such a mistake? As an argument against these hedonists, the philosopher Robert Nozick gave the example of an “experience machine” in his classic 1974 book, “Anarchy, State and Utopia.” Being plugged into the machine will generate the illusion of living a life of intense pleasure, happiness and satisfaction. Concerned that you’ll feel that you’re missing out on the real world? No worries—the machine can blot out your memory that you are in the machine.

Nozick said that he wouldn’t plug himself into the machine, and many people, including me, wouldn’t either. We want to live in the real world—to do things, not just to have the experience of doing things. Indeed, for Nozick, “it is only because we first want to do the actions that we want the experience of doing them.” More generally, “someone floating in a tank is an indeterminate blob”—and who wants to live their life as an indeterminate blob?

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Does suffering play a role in having a meaningful life? Join the conversation below.

Not everyone has the same reaction. A recent post on Twitter (from @PhilosophyTube) made me laugh, but I know that some people do think this way:

Philosopher Robert Nozick: “Now this experience machine can perfectly simulate a life in which you get everything you ever want—”

Me: “Sign me up.”

RN: “No, see, it won’t be real; you’ll think it is, but—”

Me, already plugging in: “Bye nerd.”

After all, there are those who choose to take drugs that blot out any chance of meaning and authenticity, hoping to achieve hedonic bliss. Surely, they would sign on to the machine.

It turns out, though, that exclusively seeking happiness is a mistake—even if all you care about is being happy.

Research by Brett Q. Ford and her colleagues, published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology in 2015, explores the effects of being motivated to pursue happiness by asking people to rate themselves on items such as “Feeling happy is extremely important to me” and “How happy I am at any given moment says a lot about how worthwhile my life is.” Those who highly agree with such items are less likely to get good outcomes in life and more likely to be depressed and lonely.

More Saturday Essays

- Can the Technology Behind Covid Vaccines Cure Other Diseases? February 4, 2022

- ‘No Regrets’ Is No Way to Live January 28, 2022

- The Once and Future Drug War January 21, 2022

- The Putin Puzzle: Why Ukraine? Why Now? January 14, 2022

Perhaps the self-conscious pursuit of happiness makes you think a lot about how happy you are, and this gets in the way of being happy, in the same way that worrying about how good you are at kissing probably gets in the way of being good at kissing.

But another explanation is that the happiness-pursuers often focus on the wrong things. A meta-analysis by Helga Dittmar and her colleagues, published in 2014 in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, summed up more than 200 studies and found that “respondents report less happiness and life satisfaction, lower levels of vitality and self-actualization, and more depression, anxiety, and general psychopathology to the extent that they believe that the acquisition of money and possessions is important and key to happiness and success in life.”

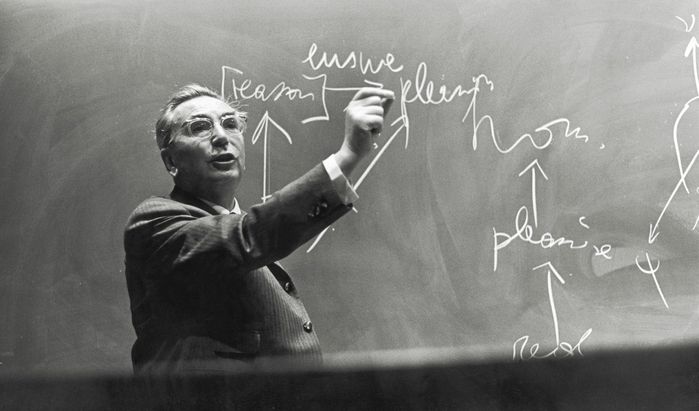

Psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl in 1967. Photo: Imagno/Getty Images

Consider the work of the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, who survived the Holocaust. In his early years practicing in Vienna, in the 1930s, Frankl studied depression and suicide. During that period the Nazis rose to power, and they took over Austria in 1938. Not willing to abandon his patients or his elderly parents, Frankl chose to stay, and he was one of the millions of Jews who ended up in a concentration camp—first at Auschwitz, then Dachau. Ever the scholar, Frankl studied his fellow prisoners, wondering about what distinguishes those who maintain a positive attitude from those who cannot bear it, losing all motivation and often killing themselves.

He concluded that the answer is meaning. Those who had the best chance of survival were those whose lives had broader purpose, who had some goal or project or relationship, some reason to live. As he later wrote (paraphrasing Nietzsche), “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how.’

“The good news is that we don’t have to choose between meaning and pleasure.”

The good news is that we don’t have to choose between meaning and pleasure. We know from the work of Baumeister and others that a meaningful life can also be a happy one. There are plenty of people who have lives of both great joy and great struggle.

Human motivation is a lot richer than many people, including many psychologists, believe. The point was nicely made by Aldous Huxley in his 1932 novel “Brave New World.” He described a society of stability, control and drug-induced happiness—a society that sacrificed everything else for the goal of maximizing pleasure. Near the end of the book, there is a conversation between Mustapha Mond, the representative of the establishment, and John, who has rebelled against the system. Mond argues heatedly for the value of pleasure. He goes on about the neurological interventions being developed to maximize human pleasure, how convenient and easy it all is, and he concludes by saying, “We prefer to do things comfortably.”

And John responds, “But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.” There is no better summary of human nature.

Mr. Bloom is a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. This essay is adapted from his new book, “The Sweet Spot: The Pleasures of Suffering and the Search for Meaning,” which will be published on Nov. 2 by Ecco (which, like The Wall Street Journal, is owned by News Corp).

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the October 16, 2021, print edition as 'Why We Choose to Suffer The Struggle for a Meaningful Life.'