What Happens to fascist architecture after fascism?

On first appearances, Bolzano in the far north of Italy is just like any other alpine town. Nestled in a valley lined by steep green hills peppered with castles, barns and churches, and terraced with vineyards, the city is a whimsical snow globe of winding streets, pastel-coloured houses and Baroque taverns.

But cross the Talfer river on the western edge of town, and suddenly it's a different story. The cosy streets are replaced by wide avenues and large, solemn squares overlooked by austere, grey buildings. The architecture is linear, monotonous and domineering, with porticoes of tall, rectangular columns and strange, looping arches that gallop across the avenues like viaducts to nowhere.

More like this:

- Why the tiny house is perfect for now

- Ten visionary ideas for the future

- Poland's extraordinary churches

Amidst this gloomy ensemble, two structures stand out. The first is the city's tax office, a hulking grey block adorned with a gigantic bas-relief depicting – across 57 sculpted panels – the unassailable rise of Italian Fascism, from the March on Rome to the colonial conquests in Africa. In its centre is a depiction of Mussolini on horseback, his right arm outstretched in a Roman salute. It's a remarkable piece of fascist agitprop architecture – awe-inspiring, odious and perplexing all at once.

The Victory Monument in Bolzano has been described as "the first truly fascist monument" (Credit: Alamy)

The second is the Bolzano Victory Monument, a striking arch made of white marble, with columns sculpted to resemble fasces, the bundle of sticks that symbolised the fascist movement. It has an ethereal, almost ghostly presence, rising like a mirage out of the grey apartment buildings and green trees that surround it. Along its frieze, an inscription in Latin reads: "Here at the border of the fatherland set down the banner. From this point on we educated the others with language, law and culture."

Erected in 1928, it's currently surrounded by a high, metal fence. It has been a rallying point for far-right marches and the object of several attempts to blow it up. The historian Jeffrey Schnapp has described it as "the first truly fascist monument".

Yet today these two pieces of fascist architectural propaganda are the centrepiece of a bold artistic experiment in addressing the debate around contested monuments, one which offers a template for other communities divided over whether to tear down or keep up monuments with racist, imperialist or fascist connotations.

Prior to World War One, Bolzano (or Bozen as it's known in German – both names are official) was the largest city in South Tyrol, a mountainous province within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Both city and province were overwhelmingly German speaking, but at the 1919 Peace Conference they were awarded to Italy on security grounds. South Tyrol would provide Italy with a natural northern border along the ridgeline of Alps, and grant it control of the strategic Brenner Pass.

As a border town with a mostly non-Italian population, it was subject to a policy of intense Italianisation under Mussolini. Place names were changed, Tyrolean cultural institutions were closed, and German – the native language of 90% of the province – was effectively banned.

The Valley of the Fallen in Spain is Franco's most notorious architectural legacy (Credit: Getty Images)

A huge new city quarter and industrial zone were built across the river from Bolzano, and thousands of Italians were encouraged to settle. The new town was festooned with numerous monuments and buildings dedicated to the "glory" of fascism.

After the War, the Italian government attempted to atone for the fascist policies by granting the inhabitants of South Tyrol a high level of autonomy. Cultural and linguistic rights would be respected, public service jobs would be allocated proportionally based on language, and 90% of tax revenue would remain inside the region.

Frequent attempts to resolve the conflict ultimately collapsed into mutual incomprehension

However, the landscape of fascist monuments remained a source of friction. "For German speakers, they were a symbol of the fascist Italianisation process which had tried to annihilate their culture and language. They wanted the monuments torn down," says Andrea Di Michele, professor of contemporary history at the University of Bolzano. "While Italians, now a majority in Bolzano but surrounded by a predominantly German-speaking province, latched on to the Victory Monument in particular as a symbol, not of fascism, but of their Italian identity in the region."

Persistent vandalism and attempted bombings saw a large metal gate erected around the Victory Monument, while the tax office had to be guarded around the clock by military police. The two buildings were used as a rallying point for rival marches between Italian- and German-speaking far-right groups. Frequent attempts to resolve the conflict ultimately collapsed into mutual incomprehension.

Nazi-era sculptures by Karl Albiker at Berlin's Olympic stadium remain standing (Credit: Alamy)

Italy is not the only country that has struggled with the architectural legacy of its fascist era. In Spain, a "pact of forgetting" meant that fascist monuments from the Franco era remained largely undisturbed until 2007, when the Historical Memory Law provided a legal framework for their removal. In 2010, an inscription glorifying Franco was removed from the frieze of the Spanish National Research Council, leaving a largely blank slate. Meanwhile the last public statue of Franco was taken down in February 2021, a move opposed by Vox, Spain's third largest political party.

Buildings that are too large to dismantle continue to pose a challenge. The University of Gijon is the largest building in Spain, built during the early years of the Franco regime in a Neo-Herrerian style, and described as having "exceptional architectural value". Yet the left-wing council in the region has repeatedly vetoed attempts to have it proposed for Unesco recognition, saying that "a building linked to Francoism cannot be a World Heritage Site".

Franco's most notorious architectural endowment is the Valley of the Fallen – a gigantic compound containing a basilica, a guest house, several monuments, a huge cross and a mausoleum containing the remains of more than 30,000 people. Franco intended it as a monument of national reconciliation and its crypt was consecrated by Pope John XXIII in 1960. But others consider it an exaltation of Francoism and have compared it to a Nazi concentration camp. In 2019, the remains of Franco were exhumed and removed, and in 2020 the government proposed turning the site into a civil cemetery. But the debate has remained largely a binary one – removal or preservation, with little in between. The contested legacy of the Spanish Civil War and Francoist rule is what makes the debate so polarised and complicated.

In Germany, meanwhile, you would struggle to find any architecture from the Nazi period. Most of it was destroyed during the War, or shortly afterwards as part of the country's denazification process. Surviving fascist buildings were simply repurposed by scrubbing away swastikas and other fascist symbols – most notably in the Berlin Olympic Stadium. Others, like the 1935 Congress Hall in Nuremberg, were chosen to house Nazi documentation centres, their monumentalism seen as symbolic of the hubris and megalomania of Hitler's architectural ambitions.

All fascist symbols have been erased from the Berlin Olympic stadium – and from all of Germany's Nazi-era architecture (Credit: Alamy)

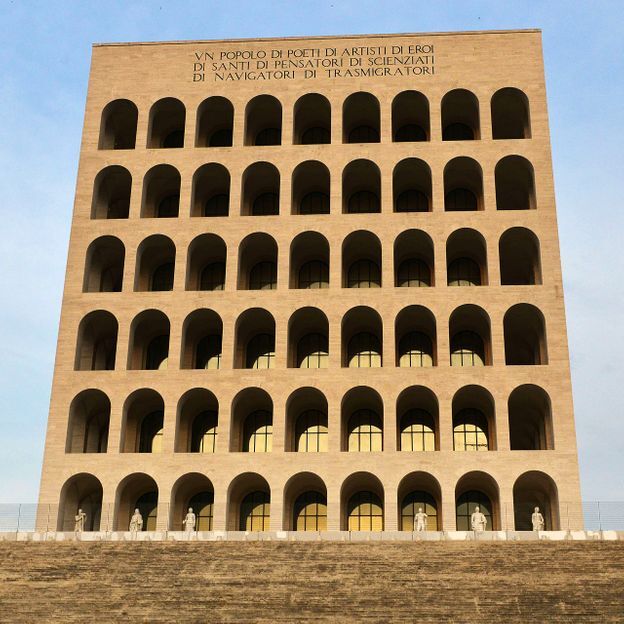

In Italy, the EUR district in Rome was conceived by Mussolini as an architectural celebration of fascism. Wandering its eerie landscape, you come across the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (also known as the Square Colosseum), whose façade is emblazoned with a quotation taken from Mussolini's speech announcing the invasion of Ethiopia. Just north of Rome's city centre lies the Foro Italico sports complex, whose entrance features a 17.5m-tall obelisk with the words MUSSOLINI DUX carved into it. Inside the Foro Italico hangs The Apotheosis of Fascism, a painting depicting Mussolini as a kind of God-Emperor. It was covered up by the Allies in 1944 for being too grotesque, and then uncovered by the Italian government in 1996.

"In Italy, which has allowed its fascist monuments to survive unquestioned, the risk is different," writes the historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat. "If monuments are treated merely as depoliticised aesthetic objects, then the far right can harness the ugly ideology while everyone else becomes inured."

Contested spaces

In 2014, a cross-communal group of historians and artists in Bolzano convened to discuss how to resolve what was becoming an increasingly fractious and emotionally charged dispute. The social dynamics of the city had turned the buildings into contested spaces, creating a necessity and a sense of urgency that a solution be found.

"The binary choice was either to destroy the monuments or leave them up," says Hannes Obermair, professor of contemporary history at the University of Innsbruck and one of the experts tasked with finding a solution to the Bolzano issue. "But if you remove the monuments, you remove the evidence, and avoid dealing with the complex layers of history and identity which drive this dispute. Alternatively, keeping the monuments up without challenging them simply normalises their fascist rhetoric."

The Palazzo della Civiltà – or "Square Colosseum" – in Rome was conceived by Mussolini as an architectural celebration of fascism (Credit: Getty Images)

In the end, a creative solution was found, one that managed to unite the city and defuse the tension between the two communities. The solution was to "recontextualise" the monuments, maintaining their artistic integrity and historical importance, while simultaneously neutralising and subverting their fascist rhetoric.

"This was an opportunity for the city to have an honest conversation about its history," says Obermair. "The disputes are less about the past than about the present. So what kind of society are we now? Are we a society riven by past ideologies or are we a democratic and pluralistic society that believes in the values of participation, tolerance and respect for humanity?"

First up the Victory Monument, which elicited strong emotions on both sides. It is explicitly fascist, extolling the conquest and colonisation of South Tyrol and the alleged superiority of the Latin civilisation. But through a complex palimpsest of ideologies and symbols, it is also seen as a celebration of Italian victory in World War One and a memorial to the fallen Italian soldiers of the war.

Their idea was simple: to take a building with explicitly fascist rhetoric, and recontextualise it as an anti-fascist monument

The monument also has significant historical value – as the first fascist monument anywhere in the world – and artistic merit, being an eminent example of Italian Rationalism, a movement now seen as important to the development of modern architecture as French Art Deco and German Bauhaus. Some of the most important Italian architects and artists of the time worked on the monument, including Marcello Piacentini and Adolfo Wildt.

The first intervention was to affix an LED ring around one of the columns, symbolically stifling the fascist rhetoric without damaging the artistic integrity of the monument. Next, a museum was built in a crypt beneath the building, which detailed the turbulent modern history of Bolzano, putting the monument's creation into context, and exploring the debate surrounding it.

Next came the bas-relief. The task fell to two local artists, Arnold Holzknecht and Michele Bernardi. Their idea was simple: to take a building with explicitly fascist rhetoric, and recontextualise it as an anti-fascist monument.

The artists decided to emblazon the Hannah Arendt quote "Nobody has the right to obey" across the frieze in German, Italian and Ladin – the region's three official languages. The quote is even more subversive when you remember that the building currently houses the city's tax office.

The explicitly fascist tax office in Bolzano has recently been recontextualised (Credit: Città di Bolzano)

"Leaving the monuments in situ allows you to contemplate the context in which they were created," explains Di Michele, who was also a member of the cross-communal taskforce. "It creates a dialogue about them and about fascism in general, and allows us to better understand the strong urban impact of fascist architecture and the far-reaching dimensions of the artistic interventions. If you move them to a room in a museum you cannot understand what impact they were intended to have and have had on the city, on the urban and symbolic layout."

The artistic interventions were a huge success, praised by politicians and civil society members from both communities. There are still occasional communal tensions, but not about buildings. That chapter has been closed. They even managed to neutralise the extremist rallies that were blighting the city.

"The Italian far-right used to assemble every year in front of the bas-relief and perform the fascist salute," says Obermair. "But with the Arendt quote there, they feel humiliated. So they've stopped coming. Likewise, the far-right groups from the German-speaking community used to rally in front of the Victory Monument to say 'Look how Italy is oppressing us', but now they can no longer say that. We've destroyed their toys, so to speak."

Obermair is enthusiastic that the Bolzano model could be successfully replicated in other parts of Italy, as well as in other countries struggling with divisive and complex fascist legacies, such as Spain. The model also offers a solution to the debate over statues in the UK and US. "Of course the social context in Bolzano is important, and each community needs to imagine its own artistic intervention," says Obermair. "But the basic idea, that we shouldn't destroy monuments but radically transform them, is a powerful one. It provides people with the tools to reflect on history, question ideology and critically examine the built environment around them. No architecture is neutral. Ultimately it is we, not the monuments, who should have the final word."

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

'建設, 建築' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Welcome to Neom, Saudi Arabia’s desert dystopia in the making (0) | 2023.01.30 |

|---|---|

| Why Is Canadian Architecture So Bad? (0) | 2022.01.26 |

| Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency review – how energy shaped the way we built the world (0) | 2021.05.30 |

| When Is the Revolution in Architecture Coming? (0) | 2021.05.11 |

| 200,000 miles of Roman roads provided the framework for empire (0) | 2021.01.28 |