Titanic: A Night to Forget

For a century the sinking of the Titanic has attracted intense interest. Yet there have been many vested interests keen to prevent media attention.

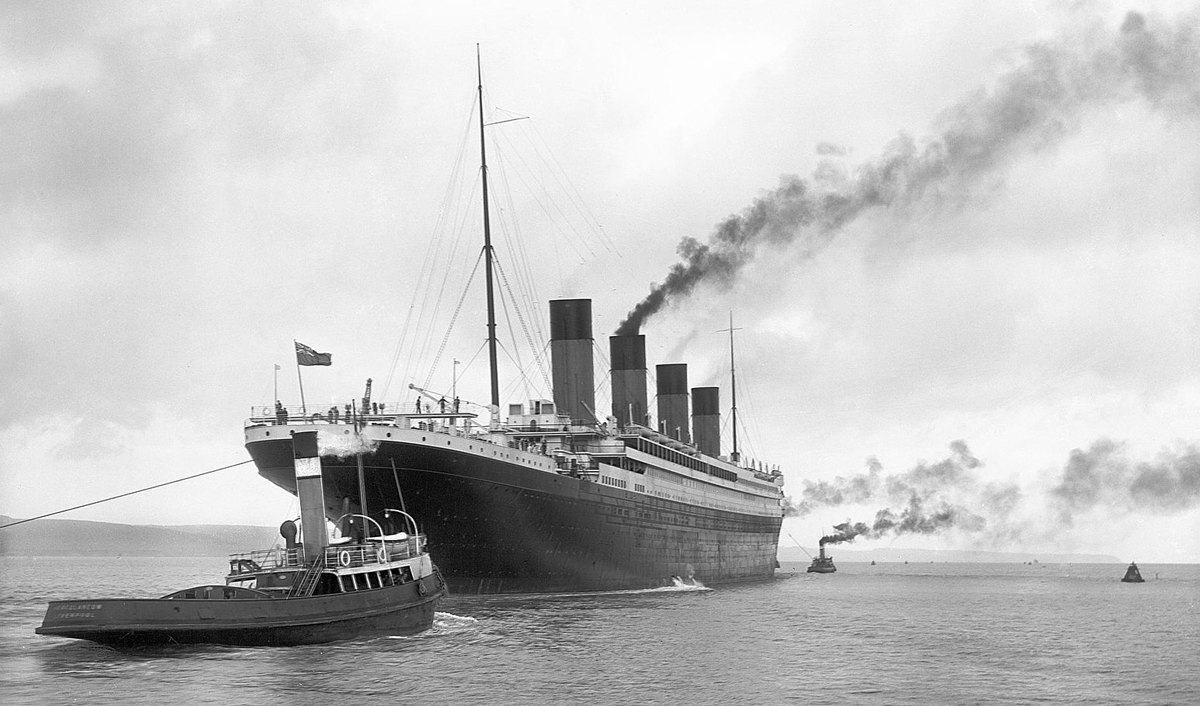

Even before the sea closed over the stern of RMS Titanic on the morning of April 15th, 1912 the task of representing the sinking – its tragic hubris, its lessons for society and above all its human cost – began in earnest. Within 40 minutes of the fatal collision the first portrayal of the disaster sparked across the airwaves in Morse code: ‘CQD [Come Quick, Danger] CQD CQD CQD CQD CQD MGY [Titanic’s radio call-sign] Have struck an iceberg. We are badly damaged. Titanic. Position 41º 44' N, 50º 24' W.’ Ever since this first broadcast the story of the Titanic has been told and retold in books, articles, films, TV and radio broadcasts, sound recordings, the visual and dramatic arts, exhibitions, computer games, websites, official and unofficial inquiries, in the courtroom and in dedicated memorials across the world.

Understandably historians have tended to focus on explaining why we have been (and remain) so fascinated by the tragedy. Straightforward answers to this question – nostalgia for yesteryear, exhilarating human drama, fascinating social dynamics, intriguing counterfactual questions and a thrilling disaster narrative – have recently come to be replaced by more sober explanations at the hands of cultural historians. According to these the dense and multiple narratives of the sinking could act as both a warning against blind faith in technology and a reassurance of the technological age (thanks to the ‘marvel’ of wireless), as a signal that modern society was ‘broken’ (given class disparities in the lost and saved, or the view that the disaster was a consequence of plutocratic greed) and a comfort that all was well (it really was a case of ‘women and children first’ and men ‘died like heroes’ in best Edwardian fashion).

The Titanic narrative could be all things to all people and its malleability made it useful for a range of storytellers over the course of the century, from the Nazis’ efforts to highlight British profiteering in their 1943 film, Titanic, to Anglo-American national and class concerns of the 1950s and the Hollywood fascination with technological nemesis in the 1970s and 1990s. By simultaneously addressing the concerns of the moment, while purporting to record the disaster for posterity, it is small wonder that the Titanic disaster has enjoyed an enduring popularity with both contemporary audiences and later enthusiasts.

What has been less apparent, however, is just how unpopular the Titanic story could be, especially within Britain. As we look back from this centenary year and see the global efforts to commemorate the disaster as the culmination of a century’s worth of interest, this seems counterintuitive. Yet over the course of the 20th century a range of different interest groups – governmental, industrial and personal – have sought to correct and sometimes suppress representations of the sinking. Where historians once thought that the relative dearth of Titanic portrayals prior to Walter Lord’s 1955 account, A Night to Remember, was due to a lack of interest, it now appears that this is also due to the efforts of a wide array of different groups. Resistance to ‘talking Titanic’ has a fascinating history of its own.

The early years

The rawness of feelings in the months immediately following the catastrophe was no impediment to those seeking to represent the event. The story remained newsworthy until the outbreak of the First World War and those elements that remain part of our cultural lexicon – the ‘unsinkable’ ship, the supposed attempt to make a record crossing of the Atlantic, the band playing ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ as the liner sank – were in place early. Some produced material on the disaster for the benefit of the bereaved: in 1912 a gramophone record containing the songs ‘Be British’ (based on the reputed last words of the ship’s captain, Edward Smith) and ‘Stand to Your Post’ was released to encourage donations to the charitable funds set up for those who lost husbands and parents. But most sought to exploit the topicality of the disaster to produce books, illustrated special issues of newspapers and magazines, magic lantern slide shows (still a going concern in 1912) and films. The first two films of the disaster, the American Saved from the Titanic and German In Nacht und Eis (In Night and Ice) were both fictionalised accounts and both produced in 1912. The American film was released in the US within a month of the sinking and starred Dorothy Gibson, a young actress who had herself survived the disaster.

Even in this initial flurry of creativity, however, there was opposition to portrayals of the disaster. Complaints were made about several of the available newsreels because footage of RMS Olympic, which was filmed more than her famous sister, was passed off as the Titanic. Beyond the concern for accuracy, however, lay some recognition of the obstacle that the feelings of the bereaved might pose for storytellers. The British cut of Saved from the Titanic was a full third shorter than the original and the delay in its European release (in July 1912) suggests some nervousness among distributors about a fictional treatment so soon after the sinking. Likewise In Nacht und Eis was copyrighted in America, but apparently not released in the wider English-speaking world.

Little was produced on the Titanic disaster in the aftermath of the First World War. The horror of death in the icy water was soon supplanted by that of the mud and blood of the trenches; on the sea, the diffuse angst and anger following the events of 1912 were replaced by a more directed and furious outrage when the Cunard liner RMS Lusitania was sunk by a German torpedo in May 1915.

Interwar anxieties

But interest in the disaster was dormant, not extinct, and it awoke in 1929 with the West End success of Ernest Raymond’s play The Berg, which was filmed as an Anglo-German co-production later that year and released with the title Atlantic. It was the first multiple-language film; the entire screenplay was re-shot in English, German and French as film-makers attempted to come to terms with the complexities of the new ‘talkies’. It was apparently popular in Britain and Europe, but despite (or perhaps because of) this popularity shipping interests in particular took a dim view of the whole enterprise. The White Star Line (erstwhile owners of the Titanic) was aghast that the makers, British International Pictures, should produce ‘a film so inimical to British interests’. This comment was uttered in despair after White Star’s efforts to stifle the production proved fruitless. It had simply found out about the film too late and the Board of Trade – to whom the shipping line complained – were sympathetic but ineffectual as it shied away from questions of censorship. The frustrated pleadings of White Star fell on deaf ears even though it pointed to the German media’s use of Atlantic (in a Bavarian newspaper) as a warning against travelling by British shipping.

The public was soon to prove less languid, however. Filson Young, a regular columnist for the Radio Times, who in early 1932 submitted a proposal for a radio play on the disaster, intended to represent it as ‘pure heroic tragedy’. A short but furious storm of protest emerged after the press got hold of the story. According to the Daily Herald: ‘The BBC is planning to give its vast public a night of horror which, in gruesome realism, is likely to surpass anything given before.’ Pointing to the significance of radio for the Titanic story the newspaper interviewed the sister of Jack Phillips, the senior wireless operator, who died in the disaster. The Evening Standard obtained comment from Sir Arthur Rostron, captain of the Carpathia (the ship that rescued the Titanic’s survivors), who was squarely opposed to the programme’s transmission.

The potential realism of the broadcast played a large part in provoking opposition to the play. The Manchester Guardian acknowledged that not merely did the story provide an opportunity for the BBC to use a ‘whole armoury of sound effects’, but that ‘the story of the Titanic is a story in sound, and silences more memorable than sound’.

Survivor memoirs point to the noise of the sinking and its immediate aftermath, followed by hours of silent waiting as the Carpathia steamed ever nearer. Moreover all this took place in the dark of a moonless night, just the sort of visual conditions recommended by Young and others to realise the potential of radio drama. In his memoir Titanic and Other Ships (1935) the liner’s senior surviving officer, Charles Lightoller, hinted at the suicide of individuals in the years after 1912, caused by their dwelling on ‘heart-rending, never-to-be-forgotten sounds’. As a ‘West-End specialist’ commented in the Daily Herald, ‘to anyone who is at all neurotic, definite damage is likely to be caused’.

Unwilling to court controversy over a play as yet unwritten, the BBC quickly announced that it would abandon the project, placing an exculpatory notice in the Radio Times and a peevish comment on the episode in its yearbook.

It might have been saved some embarrassment had it looked across the Channel, where in 1922 a radio play entitled Maremoto, which depicted the sinking of an ocean liner, had been banned by the French government as too realistic and prone to cause panic. The furore surrounding Young’s proposed play is a valuable reminder of the uncertainty surrounding the rapid pace of technological change in the interwar years. Radio broadcasters could now penetrate the inner sanctum of the home and flood the airwaves with content over which listeners had little control.

However not all programmes about the disaster proved as troublesome. Indeed Lightoller himself contributed a talk on the sinking to the radio series I Was There in November 1936. The BBC was understandably apprehensive and braced itself for the worst, but the talk proved so popular that it was repeated in 1937 and Lightoller was invited to speak again in April 1938. The success of his talks, as well as of The Berg and Atlantic, appears to confirm that the controversy over Young’s play and the earlier Maremoto can be attributed to the infancy of radio and the public’s unease with the power of the medium and those who controlled it.

But no means of representation was to prove acceptable to shipping interests, who busied themselves in the autumn of 1938 with attempts to suppress the latest film project on the Titanic, one which was to feature Alfred Hitchcock as director and David O. Selznick (whose studio produced Gone With the Wind) as producer. All the indications were that the public actively looked forward to this film, so even though Cunard White Star (the companies had merged in 1934) had waxed indignant at the earlier German use of Atlantic, the Board of Trade again made sympathetic noises, but did nothing more. This time, however, Cunard White Star took advantage of the fact that the film was to be a product of Hollywood and took their case to the US Embassy in London. At first the ambassador, Joseph Kennedy (father of the future president, John F. Kennedy), promised action, but when the Americans discovered that the Board of Trade would not oppose the film, much to the continued chagrin of the shipping companies, they were disinclined to try to get it suppressed. Hitchcock himself made all the right noises about the film ‘glorify[ing] British seamanship and heroism’, but this was a sop to the interests of the shipping business, who feared for the worst from the coming picture.

Such fears turned out to be groundless. Selznick became concerned that a planned French film on the subject would pip him to the post, that production difficulties were insurmountable and costs exorbitant and that continued British resistance would exclude the British Empire as an export market. He quietly dropped the project in the autumn of 1938, in time for a far more hostile set of film-makers to mould the Titanic narrative to their own purposes.

War and austerity

The Nazi film Titanic (1943) was one solution to a propaganda conundrum: how to attack Britain, which had been actively courted for an alliance in the 1930s and whose population, according to Nazi thinking, was not deemed ‘racially inferior’. The answer was to make the film a story of British greed, as the corrupt shareholders of White Star Line – especially the cowardly ‘Sir’ Bruce Ismay (see Southampton’s Deep Sorrow) – sought to recover from a falling share price by driving the Titanic across the Atlantic at breakneck pace and capturing the ‘Blue Riband’. The lone voice in the wilderness pointing to the folly of all this is the (fictional and German) First Officer Petersen, who only places Ismay in a lifeboat to ensure that he answers before the Maritime Board. A whitewash inevitably ensues and the film closes with the comment that ‘the deaths of 1,500 remain unatoned for, an eternal condemnation of England’s thirst for profit’.

Perhaps because the film was not released in Germany (it premiered in Prague in September 1943), it slipped through the net after 1945 as the Allied occupation authorities vetted the films of the Third Reich. Shortly after censorship responsibilities were transferred to the new Federal Republic of Germany in late 1949 the film was released, albeit with the most offensive anti-British elements (including the final ‘whitewash’ scene) removed. By March 1950 interest in Titanic was dying down in Germany, but it was only at this point that news of the film’s German release broke in Britain. Loud calls for an immediate ban prompted a revival of the film’s popularity in Germany, but a weakened Attlee government (which had just seen its majority in the Commons fall from 166 to 5) felt unable to resist calls for its suppression. A ban on it being shown in West Germany came into effect on April 1st, but naturally had no effect in the Soviet zone, where it was shown in two large cinemas less than a week later.

Battles of the Atlantic

The shipping interests were curiously silent in the furore over the Nazi Titanic, perhaps because opposition to the film was loud enough not to require the addition of their voice, but also possibly because their anxieties about representing the disaster had been roundly rejected in a recent contest with the BBC.

In November 1946 Cunard White Star discovered that the Corporation was planning another broadcast on the disaster, scheduled for the following February. It immediately complained but, following the successful broadcasts of the later 1930s, the BBC stuck to its guns. It insisted that the disaster could be legitimately treated as history and that the public was not so stupid as to suppose that the defects of 1912 were applicable in the late 1940s; to ensure this, the programme would stress the safety measures subsequently adopted by British shipping. At a meeting held in January 1947 the BBC cast aside the objections of the shipping companies, speaking confidently of the knowledge it had of public feeling. As February rolled around, the BBC appeared in complete command of the situation.

So it came as a shock when it discovered that Harland and Wolff (the Belfast shipyard which had built all White Star ships, including the Titanic) was due to launch its first postwar Cunard White Star liner on the very day of the planned transmission on the disaster. Moreover the BBC itself was to produce an outside broadcast covering the launch. Given the intransigence of the BBC over the previous months, the shipping companies realised that their approaches were likely to be rebuffed, so they employed force majeure to produce a postponement – if not cancellation – of the programme. On the same day that they wrote to the BBC about the clash, a telegram was sent to the Corporation by Basil Brooke, the prime minister of Northern Ireland, and representations were made by the Home Secretary, the Northern Ireland government and Cunard itself. Inundated, the BBC announced the postponement of the broadcast for a week, but insisted that it was entitled to produce programming on the subject of the Titanic.

Clearly, to have any effect, efforts to oppose representations of the disaster required either overwhelming public support or all the sinews of government to produce the desired effect. When they attempted to act on their own, the shipping companies failed to prevent people from engaging with the Titanic. Two examples from the 1950s show this most clearly.

In 1956 the Titanic disaster made its debut on British television. Hollywood had produced its first film on the event in 1953 and two years later Walter Lord’s bestselling account hit the shelves in the US. Its publisher in Britain, Longman, approached the BBC with a proposal for a dramatic production to coincide with the UK publication of the book. Unlike NBC in the US, which produced a classic of live TV drama with its A Night to Remember (1956), the BBC felt that a dramatic treatment was beyond its capabilities. It did, however, opt to make a documentary programme with a mix of interviews, archive footage and forensic analysis. Aware that a frontal assault on the BBC stood little chance of success, Cunard applied pressure on its current and retired employees not to assist the programme-makers. Believing that they were ‘having difficulty in finding any reliable witnesses’, Cunard’s managers felt that ‘with a little further discouragement they might of their own accord drop the idea’. But this attempt at sabotage ended in failure and the BBC’s own audience research report on the programme points to its success: over 75 per cent of those surveyed graded the programme in the top two of five possible overall ratings and this popularity was believed to be due to the factual and analytic nature of the programme.

The relative absence of dramatic embellishment also characterises what many still believe is the best Titanic film, A Night to Remember (1958), recently described by one scholar as a ‘docudrama on an epic scale’. When pitching the film to the Rank Organisation, its producer, William MacQuitty, insisted that the ship itself would be the star, but for this to ring true it was necessary to procure the use of a ship to film at least the exterior scenes. Harland and Wolff refused to have anything to do with the project – despite having assisted Walter Lord in the compilation of his account, on which the film was based – and the shipping lines urgently got in touch with one another (and anybody else with an available vessel) to stop the film-makers from obtaining the use of one. Yet the shipping lines’ call to a Clydeside ship-breaking firm came hours too late and their efforts to prevent consideration of the Titanic were again frustrated.

Portrait of a Captain

This was not the only attempt to interfere with A Night to Remember. Thanks to the widespread publicity about the film, the octogenarian Captain Stanley Lord (no relation to Walter), erstwhile Master of the Californian – the ship accused of standing by and doing nothing except count the Titanic’s distress rockets – got an inkling of how he was portrayed in the film. Without watching it or reading the book he approached his trade union, the Mercantile Marine Service Association (MMSA), to obtain assistance. His contact at the MMSA, Leslie Harrison, began a one-man crusade to clear Captain Lord’s name and managed to secure some mostly cosmetic changes to the text of A Night to Remember, conceded by the author and publishers on account of the captain’s age. The limited number and extent of these changes clearly frustrated Harrison, who was bound by the wishes of the captain during his lifetime.

But when Stanley Lord died in 1962, Harrison renewed his campaign with vigour. This culminated in the 1992 reappraisal of the conclusions concerning the Californian made by the original Board of Trade inquiry. There was no exoneration of Lord, but it was admitted that there was little he could have practicably done.

The Titanic was discovered at the bottom of the Atlantic in the early hours of September 1st, 1985. The technological success of the discovery, photography, filming and repeated visitation of the wreck has transformed the Titanic into an historical entity. James Cameron’s epic Titanic (1997) tells a human story of the disaster through a fictional, melodramatic plot, framed by a present-day narrative of crass and unethical exploitation of the wreck in the name of profit. The extreme old age of the Rose DeWitt Bukater/Dawson character (played by Kate Winslet and Gloria Stuart) in the present-day framing story is a clear sign that the Titanic has become something historical, about which fictional and exagerrated stories can be told.

But even as the ship and its sinking have passed into the past, shifting from the realm of living memory to that of myth and history, sensitivities remain. In response to local anger at Cameron’s depiction of First Officer Murdoch (shown committing suicide after shooting passengers), his local community of Dalbeattie in Scotland was given a £5,000 donation by the film-makers. Even spin-offs of the 1997 film attracted complaint. A spoof ‘making-of’ documentary constituted the lion’s share of the Christmas 1998 BBC TV special of French and Saunders. Cameron was portrayed as a foul-mouthed, gun-toting psychopath, his slick computer-generated imagery parodied as an infantile daub and the Irishness of the Titanic’s steerage passengers represented by line dancers and leprechaun puppets. Notwithstanding the clearly parodic intent, the programme still attracted complaints from viewers who felt that it was disrespectful. As late as 2007 a complaint from the last living survivor of the Titanic, Millvina Dean, about the use of the narrative in the Christmas special of Doctor Who was printed in several newspapers.

With the death of Dean in 2009 the disaster and its victims moved beyond living memory. Combined with both the demise of the passenger shipping industry and the media’s familiarity with the actual disaster, the likelihood of future controversy is small. But as Belfast and Southampton remember the Titanic this month, we should also recall how, why and under what circumstances people sought to forget the event. Only occasionally was this because of personal pain; more often, it stemmed from political, national, or industrial concerns. For most this was a night to remember; for others, however, it was one to forget.

Andrew Wells is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Edinburgh

Related Articles

Popular articles

'記憶해 두어야 할 이야기' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Neoliberalism died long before Ukraine (0) | 2022.05.16 |

|---|---|

| Look on the dark side (0) | 2022.04.28 |

| 제주 4·3사건, 그날의 진실 (0) | 2022.04.07 |

| 괴테, 아인슈타인보다 정치인이 존경받는 나라… 그래서 난 독일이 부럽다 (0) | 2022.02.13 |

| 국제그룹 해체의 진상 (0) | 2022.01.12 |