I worry, sometimes, that knowledge is falling out of fashion – that in the field in which I work, nature writing, the multitudinous nonfictions of the more-than-human world, facts have been devalued; knowing stuff is no longer enough.

Marc Hamer, a British writer on nature and gardening, said in his book Seed to Dust (2021) that he likes his head ‘to be clean and empty’ – as if, the naturalist Tim Dee remarked in his review for The Guardian, ‘it were a spiritual goal to be de-cluttered of facts’. ‘It is only humans that define and name things,’ Hamer declares, strangely. ‘Nature doesn’t waste its time on that.’ Jini Reddy, who explored the British landscape in her book Wanderland (2020), wondered which was worse, ‘needing to know the name of every beautiful flower you come across or needing to photograph it’. Increasingly, I get the impression that dusty, tweedy, moth-eaten old knowledge has had its day.

Sure, it has its uses – of course, we wouldn’t want to do away with it altogether. But beside emotional truth, beside the human perspectives of the author, it seems dispensable.

Am I right to worry? I know for a fact, after all, that there are still places where knowledge for its own sake is – up to a point – prized, even rewarded.

Some years ago, I appeared on the long-running British television quiz programme Mastermind. I did fairly well, answering questions on ‘British birds’, and afterwards I was recruited to write questions for the show, working alongside a small team of ex-contestants and quiz champs, all of whom knew a great deal more than I did about practically everything. It was an excellent schooling in what we might call raw knowledge. We didn’t have an office but, if we had, we might have pinned a motto from Charles Dickens’s Mr Gradgrind on the corkboard: ‘What I want is, Facts … Facts alone are wanted in life.’

The quiz-show contestant is, like Gradgrind himself, ‘a kind of cannon loaded to the muzzle with facts’. They are not there to impart information – the host, after all, has all the answers written on his cards. They are not there to explain anything (there’s no time for that) or show off their powers of logic or articulation. Facts, sir! The contestant is there to present facts.

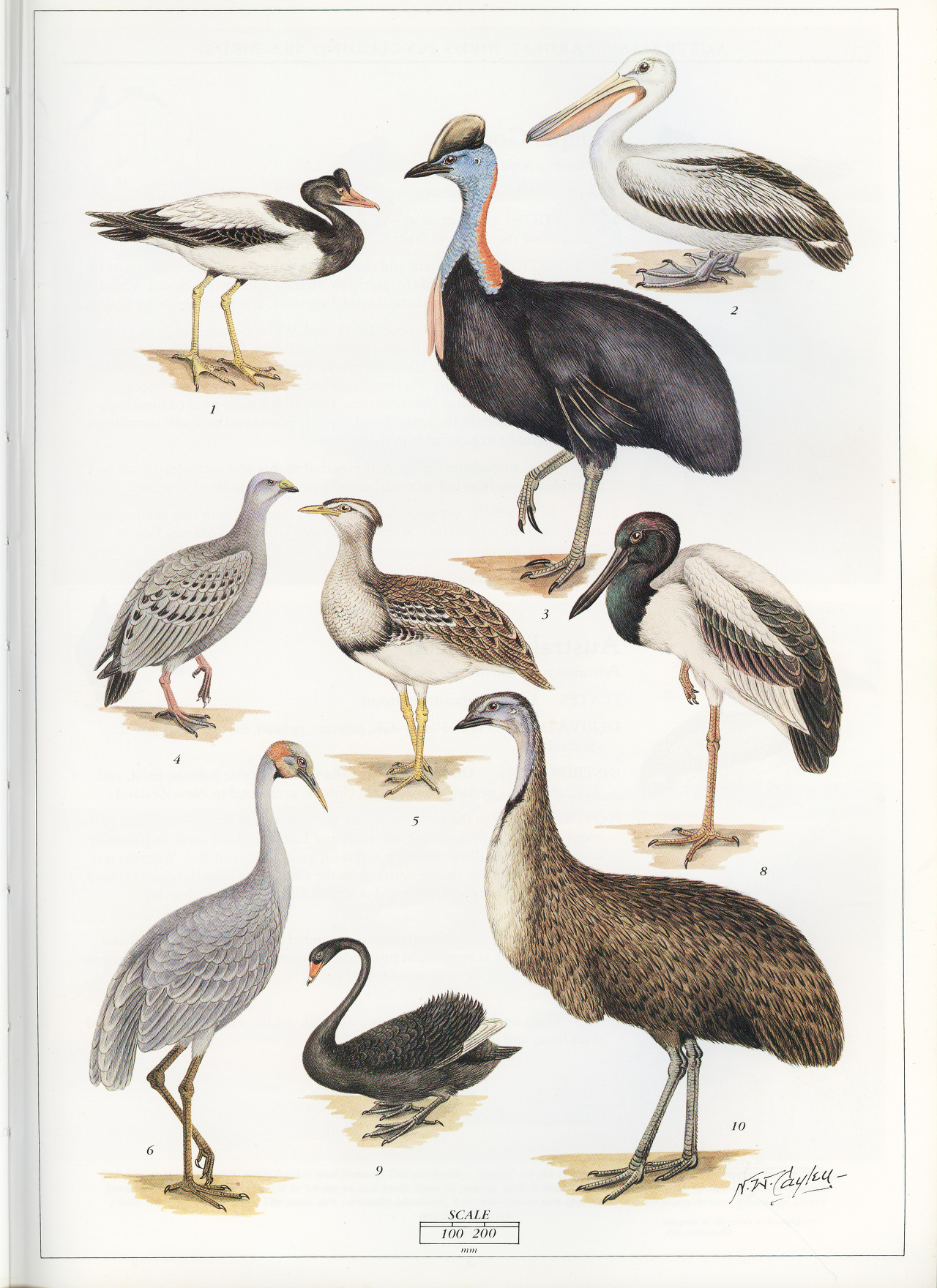

As a contestant, I duly put across my share of knowledge – the Eurasian jay! The black-tailed godwit! The peregrine falcon! And over the next few years I trafficked extensively in the same undressed product: facts about the Battle of Balaklava, Charles Schulz, Porsche cars, the Pentateuch, grime music, disaster movies, Isaiah Berlin, Tottenham Hotspur football club, malt whisky, Monty Python, John Steinbeck, the Manhattan Project; something in the vicinity of 3,000 questions: 3,000 airless, decontextualised base-units of trivia.

At the end of each season, the Mastermind champion is presented with a beautifully engraved glass bowl – and no money, this being the BBC and not NBC, where the closest US equivalent is Jeopardy! It’s a pretty big deal, among people who care about this kind of thing. Knowing stuff, just knowing it, still has some cachet, some meaning.

Meaning is of course fundamental to knowing – the search for the significant datapoint, the sifting of the signal from the noise. Yet there are as many ways of finding meaning in nature as there are people on our planet – as there are people who have ever lived.

The American poet Wallace Stevens wrote of 13 ways of looking at a blackbird. Perhaps there are different ways of knowing about a blackbird, too; perhaps, in different knowledge systems, different traditions of learning, there are different blackbirds.

Natural history can certainly accommodate a profusion of perspectives – indeed, it will always benefit from greater diversity in how we look and think. But I wonder if there are unhelpful dichotomies in play, where we pit ‘knowledge’ against lived experience, against emotional engagement, and where the idea of scientific expertise in nature summons nothing in us but Linnaean binomials, mothballed drawers of beetles, airless data, the charts and graphs of dead white European men.

The English journalist John Diamond, shortly before his death from throat cancer in 2001, wrote that ‘there is really no such thing as alternative medicine, just medicine that works and medicine that doesn’t’. Ecological knowledge might be thought of as similarly indivisible. There are no alternative birds, non-traditional plants, complementary ecologies. More often than not, bodies of knowledge develop not in opposition to one another but along parallel tracks.

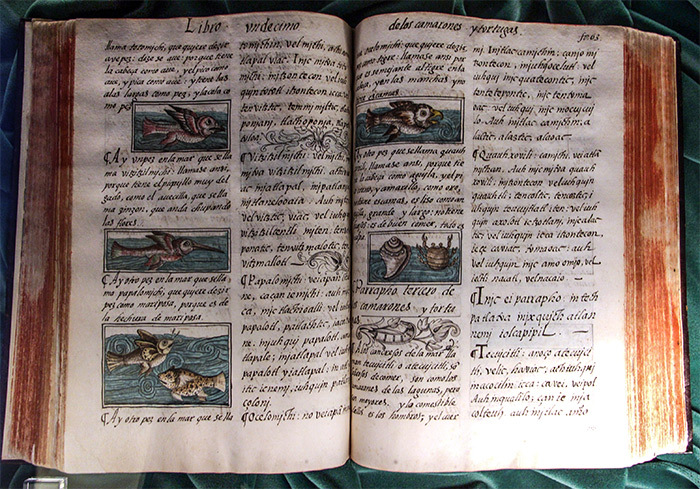

The Florentine Codex, for example, was compiled between 1558 and 1569 by the Spanish scholar Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, with the aim of documenting Indigenous Aztec knowledge of the natural history of the Valley of Mexico: around 725 life-forms are catalogued, very much in accordance with any modern zoological survey. A 2008 study of Indigenous names for plants in the Ejina area of Mongolia showed a high degree of correspondence with ‘scientific’ names (‘a total of 121 folk names of local plants have correspondence with 93 scientific species’). Research among the Akan people of Ghana in 2014-15 found that Indigenous bird-naming systems ‘follow scientific nomenclature’.

None of this, to be clear, is a question of one body of knowledge requiring corroboration or validation from another. Rather, this is about overlap and commonality; more than that, it makes the point that knowledge, the knowing of things, identification, distinction, naming, is a foundation of any understanding of the more-than-human world.

‘The term “traditional knowledge” is not in keeping with the Inuit definition of the world around us,’ argue the Inuit rights activist Rosemarie Kuptana and the author Suzie Napayok-Short. This term, imposed by ‘outsiders’, limits the Inuit way of knowing (Inuit Ilitqusia) to the past, reducing it to ‘a source viewed as anecdotal evidence and of little consequence for inclusion in discussions that impact Inuit in the Arctic.’ Rather, it is the dictionary definition of ‘science’, they point out, that ‘closely reflects the Inuit Way of Knowing’. The Inuit do not dismiss ecological knowledge – the whats and wheres of the places they inhabit – as clutter. Far from it.

The ecological knowledge of generations was mapped out across these five-foot sheets

In the 1970s, the Canadian government commissioned the Inuit Land Use and Occupancy project, to establish the ‘nature and extent of Inuit use and occupation’ of the Arctic – the Inuit being a people who live lightly on the land, leaving few permanent traces. The project leaders – not themselves Inuit – wanted to better establish the Inuit ‘way of owning their world’, as the anthropologist Hugh Brody wrote in 2018. Perhaps because love cannot be marked on a map, because complex relational concepts such as respect and familiarity aren’t easily quantifiable, knowledge, as a product of the lived experience of the Inuit, came to define Inuit possessions in the Arctic.

The maps drawn up by the Inuit through the occupancy project are maps, therefore, not of infrastructure or architecture but of lived knowledge, knowledge hard-acquired – what Brody calls ‘[the] most valuable tool’ of people who hunt. Long lists of every creature and plant hunted or gathered by the Inuit became the basis for the occupancy project maps: each Inuit hunter was asked to show where in their territory they had hunted harp, ringed or bearded seal; where they had trapped Arctic fox; where they had fished for Arctic char, sculpin, sea-trout, cod; where they could find eider duck or tundra geese, collect the eggs of Arctic terns or black guillemots, gather blueberries or cranberries. The maps, gradually, collaboratively, came to show caribou movements, bear denning sites, the reaches of open water where narwhal could be hunted. Brody describes the maps as biographical – since they also detail sites of historical, family and community interest. But they are also, of course, ecological. The ecological knowledge of generations was mapped out across these five-foot sheets.

Knowledge alone cannot define Inuit relationships with Inuit land (it cannot alone define any human relationship with anything). The emotional and spiritual bonds between people and land are complex and perhaps unfathomable.

But they depend upon the hard groundwork of knowledge, of knowing what is what. It would be perverse to think that Indigenous people, over-cluttered with data, encumbered by facts, are missing out on some sort of spiritual clarity.

Ecological knowledge like that of the Inuit is, of course, not concerned only with opportunity; people who make their living in landscapes that can kill you are also intimately familiar with risk. The British nature writer Jon Dunn, travelling in Alaska in search of rufous hummingbirds in his book The Glitter in the Green (2021), strikes up a conversation with two Yup’ik men on their way to work at a fish-processing plant in Cordova:

We’ve got bears here. Where you’re going, there’s bears … You need to take care, man … My dad, he was a hunter … He always told us to watch out for bears. You’re best carrying a gun.

There are further warnings when the conversation turns to killer whales: ‘They’re really bad news, my dad always said. He didn’t like them at all. You can’t trust them.’

It’s the sort of well-informed bio-realism that one would expect to see from anyone who has lived observantly, thoughtfully, among wild things. Every writer on nature comes to their own accommodation with the hard facts of wild life. We needn’t all look at them too closely, or for too long – but, if we don’t look at them at all, I’m not sure what our writing is for. Where we connect with nature, we make a complicated music. We lose a good deal, I think, if we miss or mute the minor chords.

Nature writing that turns aside from detail, that comes from a place of rarefied factlessness, can feel to me unmoored, and adrift. In Wanderland, Reddy, searching for spiritual connection in the landscape, watches ‘a bird of prey soar[ing] overhead. A hush descends and the bird’s presence feels like a blessing. I can feel the emotion pouring from it, a kind of love and wildness and wisdom.’ It isn’t only that I don’t recognise this sort of connection with wild things (though I don’t): it’s that I can’t see any secure points of correspondence, any way to map the feeling to the facts.

It’s telling to set Reddy’s bird of prey, whatever it was, alongside others from the past few years of British nature writing. Consider three goshawks (these hulking forest raptors have a magnetic appeal for nature writers). In Helen Macdonald’s genre-shaping memoir H Is for Hawk (2014), a falconer advises:

If you want a well-behaved goshawk, you just have to do one thing. Give ’em the opportunity to kill things … Murder sorts them out.

The ornithologist Conor Mark Jameson admits in Looking for the Goshawk (2018) to ‘sometimes flinch[ing] at the deadly ruthlessness’ of his subject (even as he finds in it ‘a kind of haunting’). Most starkly, in Goshawk Summer (2021), the photographer and filmmaker James Aldred watches a ‘gos’ bring the severed head of a baby robin home to its own chicks:

Its puffy red eyes are closed as if sleeping … It’s a pitiful sight made all the more poignant from knowing that the chick would have instinctively reached up to beg for food as the hawk’s shadow fell across it … For a goshawk, it sometimes seems as if life is simply nature’s way of keeping meat fresh.

Macdonald, Jameson and Aldred are immensely knowledgeable writers. All three, evidently, have formed deep emotional attachments to the goshawks they have studied, but all three acknowledge, too, that these attachments are – to say the least – complicated; that these birds are brutal, that wild life is hard life, that whatever it is we see in the goshawk, whatever the goshawk may show us of ourselves, it may not be pretty, may have little to do with harmony and love, may indeed be something we do not much care to be shown.

The complex relationships that can emerge between human and nonhuman participants in an ecology or landscape have to do with knowledge, of course, with what one knows of the other and the other of the one, but there may be a better term for this kind of knowing. Introducing Great Possessions (1990), the journals of the Amish farmer David Kline, Wendell Berry notes that Kline writes ‘not just from knowledge, but from familiarity. And that distinction is vital, for David’s acquaintance with the animals, birds, plants, and insects that he writes about is literally familiar: they are part of his family life.’ Berry is referencing Kline’s immediate family, his wife and children and their shared enjoyment of the natural world, but also the idea of nature as family, as something known intimately, something everyday, something close (these are the earliest meanings of familiar in English).

The Korean writer and photographer Sooyong Park expresses a subtle variant on familiarity, on intimate knowing, in his remarkable book The Great Soul of Siberia (2015):

You must have faith. Walking through the woods, you often come across owl pellets … When you find one of these, you know an owl is sitting on a branch over your head, looking down at you. You may be overcome by the urge to look up and see the owl for itself. But the moment you give in and look up, the owl will fly away. I trust the owl is up there and continue on my way … Trusting an animal is there by looking at its traces rather than pursuing the animal itself: this is faith in nature.

I heard an unsentimental echo of this when one autumn day I was out with an expert birder on a woodland patch near where I live in Yorkshire. Something small and yellowish called briefly in a tree as we passed. ‘Blue tit or great tit?’ I queried – both are very common birds here. ‘This is why I don’t work on the census,’ the birder said, trudging on. ‘I don’t give a shit.’ Subtle are the ways of those who know things.

Knowledge is not only a matter of seeing what is. It can also be a matter of seeing what is not, or not quite, not exactly – seeing the shadows of one thing in the shapes of another.

Science and metaphor have always maintained a busy two-way trade: think, perhaps, of the dream-image of the snake biting its tail that led August Kekulé to the structure of the benzene ring in 1865, or of the ‘tangled bank’ that illustrates the emergence of complex and interdependent life from fundamental laws of variation and inheritance in Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). Samuel Taylor Coleridge, asked why he attended lectures on chemistry, replied: ‘To improve my stock of metaphors.’ Writers on nature, too, readily commit to metaphor and symbol, and so J A Baker’s peregrine falcons stand for death, and any English undergrad can tell you what the white whale Moby-Dick represents (two or three of them might even agree).

Is moss, though, choosing to live as it does? Is moss generous?

The Tewa author and scholar Gregory Cajete stresses the centrality of ‘the metaphoric mind’ not only to Native science but to ‘the creative “storying” of the world by humans’. We are always interpreters – even at our most baldly empirical, we are at one remove from the action, and in that sense we are always storytellers.

The pursuit of metaphor in nature introduces once again the question of how humans should be expected to engage or interlock with the nonhuman world; what are we to it, and what is it to us? Annie Dillard, in Teaching a Stone to Talk (1982), lightly derides the idea of mapped point-to-point learnings from wild things: ‘I don’t think I can learn from a wild animal how to live in particular – shall I suck warm blood, hold my tail high, walk with my footprints precisely over the prints of my hands?’ Dillard instead seeks to take broader lessons, in ‘mindlessness’ and ‘the purity of living in the physical senses’.

The Potawatomi biologist and nature writer Robin Wall Kimmerer is less cautious. In an interview with The Guardian in 2020, she spoke of what the study of moss might teach us: ‘of being small, of giving more than you take, of working with natural law, sticking together. All the ways that they live I just feel are really poignant teachings for us right now.’ Is moss, though, choosing to live as it does? Is moss generous (is it meaningful to speak of the generosity of moss?) The shift from literary or explicatory metaphor to moral allegory feels profound and somewhat destabilising.

We see the same sort of thing in a recent work of British landscape writing, Anita Sethi’s I Belong Here (2021), in which the author considers a blade of grass:

Can you imagine a blade of grass having low self-esteem, being made to hate its colour or shape? Despite being so literally trodden upon, it is so sure of itself, so confident in its skin. Be more like grass growing, I think.

We are in the same moral-imaginative realm here as the classic fables of the scorpion and the frog, or the grasshopper and the ant. Certainly, we can find fables in nature – an infinite range of them, exemplifying whatever lesson we wish to hear – and, through these fables, we might come to understand new things about ourselves. How much these selective lessons can tell us about the nonhuman, however, is a different question.

In Homing (2019), his book on pigeons and the sport of pigeon-racing, Jon Day recounts a conversation with Rupert Sheldrake, a parapsychology researcher best known for his theory of morphic resonance (the idea – generally regarded as pseudoscience – that ‘natural systems … inherit a collective memory from all previous things of their kind’). ‘The question of whether or not he was correct,’ writes Day, ‘did not feel particularly important: it was as a metaphor that I was most interested in the notion of morphic resonance … The attractiveness of his theory stems from the fact that it suggests we are all connected: part of a web of memory linked by the morphic field.’ This seems less a metaphor than an exercise in wishful thinking: it would be nice if this were true.

Kimmerer, however, does have a true talent for metaphor. A wonderfully affecting chapter in Braiding Sweetgrass (2013) draws on the author’s botanical knowledge in exploring her bittersweet experience of motherhood. Raking pondweed from a long-clogged pond on her family smallholding, she reflects on the hexagonal structures of the alga Hydrodictyon and its system of clonal reproduction:

In order to disperse her young, the mother cell must disintegrate, freeing the daughter cells into the water … I wonder how the fabric is changed when the release of daughters tears a hole. Does it heal over quickly, or does the empty space remain?

Analogy rather than fable; enlightenment, rather than instruction.

The English novelist John Fowles made a subtle case against the sanctification of names and knowing in his short book The Tree (1979). Having experimented with what he calls ‘Zen theories’ of aesthetics, of learning ‘to look beyond names at things-in-themselves’, he concludes that ‘living without names is impossible, if not downright idiocy, in a writer’:

I discovered, too, that there was less conflict than I had imagined between nature as external assembly of names and facts and nature as internal feeling; that the two modes of seeing or knowing could in fact marry and take place almost simultaneously, and enrich each other.

There are fair reasons to mistrust knowledge and those who have it. It can be (and is) used to gatekeep, to exclude those who lack it – that is, those who lack the background, education or life circumstances necessary to have acquired it. More fundamentally, there are problems with competitive hierarchies of knowledge in which certain knowledge forms or learning traditions are privileged or elbowed out, with concomitant impacts on justice and representation across a host of sociopolitical variables (class, ethnicity, sex and culture among them). It can also be hard not to track the obvious connections – historical, cultural, though perhaps not inevitable – between identification, collection, colonialism and plunder.

In The Tree, Fowles is shamefaced in confessing his tendency to approach nature – orchids, in particular – avariciously, thinking of nothing more than ‘identifying, measuring, photographing’, and, ultimately, not seeing, ‘set[ting] the experience in a sort of present past, a having-looked’ (in his journals, Fowles in fact confesses to rather more: he was prolific in collecting, smuggling and attempting to naturalise rare orchids in his English garden). The book – an essay, really – argues against formalised knowledge and in favour of an untutored, undirected appreciation of nature (this ‘green chaos’) – a mode of appreciation we more readily associate with art than with scientific subjects. ‘In science greater knowledge is always and indisputably good,’ he writes. ‘It is by no means so throughout all human existence.’

The Tree also offers up an unexpected – indeed, accidental – characterisation of ‘nature writing’ as we know it in the UK. When Fowles writes of ‘its personal interpolations, its diffuse reasoning, … its frequent blend of the humanities with science proper – its quotations from Horace and Virgil in the middle of a treatise on forestry’, he is describing science writing as it existed before the specialisation and professionalisation of the Victorian era (at around the time Charles Waterton was warning of naturalists who spend more time in ‘books than bogs’). He might as well, however, be talking about the latest prize-shortlisted book on hiking with otters or finding peace among botflies (in British nature writing, the feather-footed shadow of Evelyn Waugh’s ‘questing vole’ is never far away). But what Fowles goes on to say is, in my view, the real strength of ‘nature writing’ done well: ‘that it is being presented by an entire human being, with all his complexities, to an audience of other entire human beings’.

How can we be moved or inspired or enchanted without a clear sight of what we are enchanted by?

Writing on nature is an ecology of knowledge forms. There is scope for immense variation and fruitful cross-pollination. Traditions in science writing inform work that builds on native knowledge or transcendentalism, and vice versa; writers rooted in materialism (‘I am deeply a materialist,’ says Richard Mabey, ‘but if materialist has a bad ring, call me a matterist’) engage in profound ways with the emotional or cultural content of the living world around them; fresh light (or deeper shade) is thrown on to known facts by writers for whom the self is the starting point.

Not that there isn’t a degree of friction. In recent years, writers in this last subcategory have for many readers come to define what is meant by ‘nature writing’, in the UK if not beyond. Robert Macfarlane has been foremost among them since at least 2007 and the publication of his landscape exploration-cum-meditation The Wild Places.

Macfarlane’s considerable influence extends beyond his own books: it has been joked before that his forewords, afterwords, introductions and prefaces would fill a hefty volume (to which we might add that his generous cover blurbs might furnish a considerable appendix). Like H Is for Hawk and Amy Liptrot’s memoir The Outrun (2015), his work has contributed to the construction of British nature as an emotional space, and of nature writing as a form that is more about the writer than about the nature.

The idea, of course, is not new – and nor is the friction. In 1946, the ornithologist James Fisher bitterly lamented the Romantic influence on nature writing:

Oh, the critics and reviewers, the weekly columnists, the nature correspondents, who find Nature ‘charming’; who find [Gilbert] White’s Selborne ‘charming’; who find the emotional, romantic outpourings of [Richard] Jefferies ‘charming’; who find the humourless introspection, the self-conscious pessimism, the nostalgic obscurantism of [W H] Hudson ‘charming’; and who lump them altogether in their charming paragraphs to charm those to whom the country is a plaything!

Fisher wanted to hear only from observers, from those who offered reportage, data, information, who took the study of nature seriously, who added things to our knowledge of nature and in doing so renewed and reshaped it. This is no small thing – there is a greater cause here, for Fisher. Facts, from this perspective, are the foundation of our understanding, from which all else follows. How can we be moved or inspired or enchanted without a clear sight of what we are enchanted by? We might as well be writing poetry about cardboard scenery. One needn’t be a pedant or a Gradgrind to sympathise.

Even if we do seek only to observe, to see, to be Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ‘transparent eyeball’ (or long-legged walking eyeball, splendid in tailcoat and hat, in C P Cranch’s satirical sketch of the great Transcendentalist) we are still not quite on neutral ground. We may be looking, but which way are we looking? Out, or in? The importance of nature, for Emerson, lay in its relation to humankind. Without the human gaze, the human filter, nature was an instrument lying idle. People, in this sense, were the point of nature.

We can never entirely escape from human-centric narratives of nature; they have always been our primary means of interpreting and coming to terms with the landscapes in which we find ourselves. Kimmerer writes of a thanksgiving address among the Onondaga, ‘The Words That Come Before All Else’, in which the speaker expresses gratitude for the fish who ‘give themselves to us as food’, the fruit and grains that ‘helped the people survive’, and so on. We are a part of the living world, of course – but also, the living world is important because we are important.

It feels like a heretical statement, in our age of anthropic guilt: we are important. But of course we are important, to us, and, if we weren’t, then there would be little point in any sort of nature writing, because the nature writer’s job, after all, is to build, no, to be a bridge between two cultures (or more) – to pull together the world of us and the world of not-us. It’s all translation, and any good work of translation must value the ‘to’ as well as the ‘from’.

In Birds Art Life (2017), the Toronto-based author Kyo Maclear writes that the best writing on nature ‘capture[s] the sweet spot between poetic not-knowing and scientific knowing’. I like this – and I think there’s much to like, too, in what we find as we pitch between these two poles, in almost-knowing, sort-of-knowing, best-guess knowing, not-sure-how-I-know-but-I-know knowing (in a writer, being honest is a far better thing than being sure).

I’m a matterist – ah, hell, I’m a materialist. I’ll always value knowledge for its own sake (aside from anything else, it’s the only way to do well on TV quizzes). But when we speak of nature we are always, always speaking of ourselves – our voices give us away, every time – and what we observe at our end of the telescope, what we see in ourselves, what passes between us and not-us, will never not matter (I’m thinking again of the things the Inuit couldn’t put on their maps).

This is knowledge, too, as much as the Latin name of a bird or the distribution pattern of a wildflower or the shade of a moth’s wing. The trick, as always, is to see it clearly, and catch it cleanly.