From Voltaire and Rousseau to Sartre and De Beauvoir, France has long produced world-leading thinkers. It even invented the word ‘intellectual’. But progressives around the globe no longer look to Paris for their ideas. What went wrong?

Philosophy

From Voltaire and Rousseau to Sartre and De Beauvoir, France has long produced world-leading thinkers. It even invented the word ‘intellectual’. But progressives around the globe no longer look to Paris for their ideas. What went wrong?

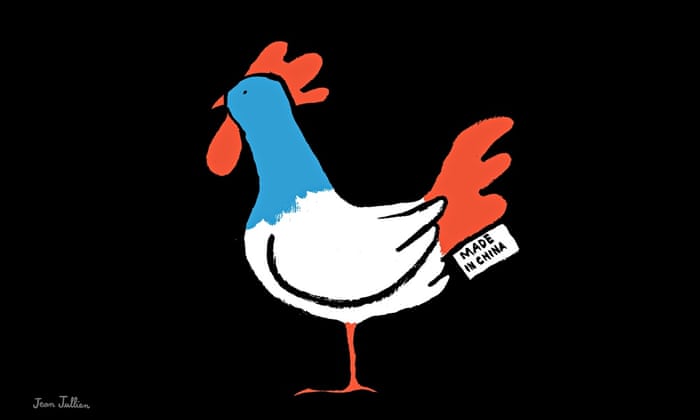

French thought is in the doldrums. French philosophy, which taught the world to reason with sweeping and bold systems such as rationalism, republicanism, feminism, positivism, existentialism and structuralism, has had conspicuously little to offer in recent decades. Saint-Germain-des-Prés, once the engine room of the Parisian Left Bank’s intellectual creativity, has become a haven of high-fashion boutiques, with fading memories of its past artistic and literary glory. As a disillusioned writer from the neighbourhood noted grimly: “The time will soon come when we will be reduced to selling little statues of Sartre made in China.” French literature, with its once glittering cast of authors, from Balzac and George Sand to Jules Verne, Albert Camus and Marguerite Yourcenar, has likewise lost much of its global appeal – a loss barely concealed by recent awards of the Nobel prize for literature to JMG Le Clézio and Patrick Modiano. In 2012, the Magazine Littéraire sounded the alarm with an apocalyptic headline: “La France pense-t-elle encore?” (“Does France still think?”)

Nowhere is this retrenchment more poignantly apparent than in France’s diminishing cultural imprint on the wider world. An enduring source of the French pride is that their ideas and historical experiences have decisively shaped the values of other nations. Versailles in the age of the Sun King was the unrivalled aesthetic and political exemplar for European courts. Caraccioli, the 18th-century author of L’Europe Française, expressed a common view when he enthused about the “sparkling manners and lively vivacity” of the French, before concluding: “Every European is now a Frenchman.” Through the revolutionary epics of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, French civilian and military heroes inspired national liberators throughout the world, from Wolfe Tone in Ireland and Toussaint L’Ouverture in Haiti to Simón Bolívar in Latin America. The Napoleonic Civil Code was widely adopted by newly independent states during the 19th century, and the emperor’s art of war was celebrated by progressive writers and poets across Europe, from William Hazlitt to Adam Mickiewicz, but also by Japanese samurai warriors and Tartar tribesmen (a Central Asian folk song celebrated “Genghis Khan and his nephew Napoleon”), and by the Vietnamese revolutionary hero Võ Nguyên Giáp. In the late 1930s, when he was a history tutor at the Than Long school in Hanoi, Giáp taught French revolutionary history; one of his students later recalled the “mesmerising” quality of his lectures on Napoleon.

Progressive men and women across Europe celebrated the heritage of the 1789 revolution throughout the 19th century, and the first generation of Russian Bolsheviks was obsessed by the analogies between their own revolution in 1917 and the overthrow of the French ancien régime. Lenin drew on the Jacobin heritage as an inspiration for his own revolutionary organisation in Russia, and dismissed those who opposed him as “Girondists”. Stalin’s francophilia extended to obsessively reading the novels of Victor Hugo. French ideas and symbols were universally equated with self-determination and emancipation from servitude: the Statue of Liberty, the iconic emblem of American-ness, was designed by the French sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi; Poland’s national anthem celebrated Napoleon Bonaparte, while Brazil’s flag bore the motto “order and progress”, after Auguste Comte’s motto of positivism. French inspiration was most evident in stimulating traditions of critical and dissenting inquiry about modern society: Olympe de Gouges’s Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen (1791) was embraced by champions of feminine emancipation across the world, while social inequality and political oppression were eloquently denounced by Rousseau and the radical republican tradition of Babeuf, Buonarroti and Blanqui all the way through to the works of Sartre, Fanon, Foucault and Bourdieu. Yet little of this ideological fertility is now in evidence, and French thinking is no longer a central point of reference for progressives across the world. It is noteworthy that none of the recent social revolutions, whether the fall of Soviet-style communism in eastern Europe or the challenge to authoritarian regimes in the Arab world, took their cue from the French tradition.