The Rise and Fall of Nimrud

Before its untimely end this once great city was the centre of a vast and powerful civilisation.

'The

Palaces at Nimrud Restored', 1853, imagined by the city's first excavator,

Austen Henry Layard and architectural historian James

Fergusson

'The

Palaces at Nimrud Restored', 1853, imagined by the city's first excavator,

Austen Henry Layard and architectural historian James

Fergusson

When the Islamist terror group ISIS used hammer blows, bulldozing and explosions to destroy the ancient city of Nimrud in March this year, they wiped out a relic of Iraq’s glorious past.

Nimrud (known in ancient times as Kalhu) was once a major city and briefly the capital of the great Assyrian state that collapsed in the late seventh century BC. Its ruins, first excavated in the mid-19th century and then in much greater detail in the 20th century, are dated to the second millennium BC, although the city’s role within the broad sweep of Mesopotamian history takes us back to nearly 2000 BC, when a separate Assyrian state emerged.

The word Assyrian comes from the city of Ashur on the west bank of the Tigris about 300 km north of Baghdad and 100 km south of Mosul. In the early second millennium BC it became an important entrepôt, whose great trading houses and their colonies in central Anatolia organised trade that sent copper and tin – the constituents of bronze – in one direction and finished textiles in the other. As a city state it gave allegiance to no one and was ruled by a vicegerent on behalf of the god Ashur.

Then in the mid-18th century BC Babylon suddenly arose to prominence and Assyria went into decline, only emerging from the shadows in the 14th century under a bold king named Ashur-uballit (1365-30 BC). At the start of his reign the major players in the Near East were Egypt, Babylonia and the Hittite Empire and in his unsolicited greeting-gift to the Egyptian king (a chariot and pair of horses, plus a choice stone of lapis lazuli) Ashur-uballit dared not address him as an equal. By the time of his next letter to Egypt, military success had emboldened him and he demanded substantial return gifts. He married one of his daughters to a prince of Babylon and when his grandson, as king of Babylonia, was assassinated in favour of another claimant, an aged Ashur-uballit immediately attacked the city, executed the usurper and placed his own choice on the throne.

Having made Assyria one of the great powers in the Near East with Ashur as its capital, he was succeeded by a series of some dozen kings who expanded the state and created regional administrative centres including Kalhu (Nimrud), built, or at least rebuilt, by Shalmaneser I (1274-45). Assyria remained a powerful state, even when Mediterranean lands were attacked in about 1200 BC by the ‘Sea Peoples’ (including Philistines and Arameans), but the Arameans caused increasing trouble and, after the reign of a powerful king, Tiglath-pileser I (1114-1076), the Middle Assyrian period came to an end.

The Neo-Assyrian period started in 934 BC when a succession of three strong kings re-asserted Assyrian control, using the spoils of war for great new building works and the consolidation of state power. This set the stage for an immensely powerful king, Ashurnasirpal II (883-59), who mounted far-reaching campaigns northwards and to the west, where he ceremonially washed his weapons in the Mediterranean.

He transferred the capital from the ancient city of Ashur to Kalhu and his victorious rule brought great wealth that he ploughed into this massively rebuilt city, where the surviving carvings, by craftsmen imported from abroad, show a quality far outshining anything produced under his predecessors. The construction and decoration of the magnificent palace and temples is described in detail on the ‘banquet stele’, a sandstone block bearing a 154-line inscription and an image of the king. The inscription also describes herds of wild and exotic animals, the digging of a canal to supply the city with orchards and the palace gardens with fragrant plants and fruit-bearing trees:

The canal cascades from above into the gardens. Fragrance pervades the walkways. Streams of water [numerous] as the stars of heaven flow in the pleasure garden.

To cap it all the text gives a long and detailed list of the food provided at a banquet thrown to celebrate the opening of the palace, at which numerous guests feasted for ten days:

I gave them food, I gave them drink, I had them bathed and anointed. [Thus] did I honour them.

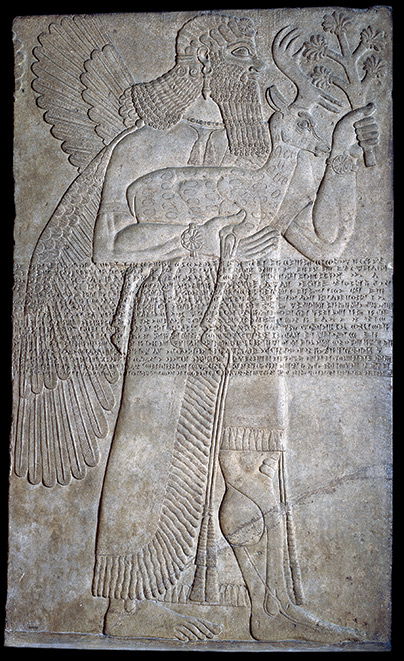

It was during Ashurnasirpal’s reign that magnificent narrative reliefs began to appear – kings and gods and colossal statues of human-headed winged bulls, inscribed with cuneiform writing – portraying the ever-increasing power of Assyria which over the next quarter-millennium turned into one of the greatest empires the world had ever seen.

Towards the end of the seventh century BC, Assyria collapsed. Babylon took over before being conquered by the emerging Persian Empire in the mid-sixth century, which in turn fell to Alexander the Great two centuries later.

Empires rise and fall, and ISIS, who want to found a new one – a Caliphate embracing the Islamic world – will surely fail. In the meantime, the remains of Nimrud leave a hole in history, vandalised for the sake of nothing.

Mark Ronan is Honorary Professor of Mathematics at University College London.

'寫眞' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 한국 현대사의 최대 미스터리 (0) | 2015.10.06 |

|---|---|

| 광복후 한국은 '결핵 공화국'… 9세 少女 몸엔 1063마리 기생충도 (0) | 2015.10.06 |

| 1948年の韓国・ソウル。戦火を逃れた貴重な写真の数々(モノクロ画像) (0) | 2015.10.06 |

| 빌딩화재의 화염을 뚫고 5마리 새끼고양이를 모두 구해낸 어미고양이 (0) | 2015.09.29 |

| 프란츠 페르디난드 오스트리아 황태자가 마지막 입었던 피묻은 코트 (0) | 2015.09.29 |