We talk so much about innovation these days that it has become a buzzword, drained of clear meaning. So in my latest book, The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution, I set out to report on how innovation actually happens in the real world by focusing on a dozen or so of the most significant breakthroughs of the digital age and the people who made them. How did the most imaginative innovators of our time turn disruptive ideas into realities? What ingredients produced their creative leaps? What skills and traits proved most useful? And, most importantly as I discovered, how did they think and lead and collaborate?

Throughout history the best leadership has come from teams that combined people who had complementary talents. That was the case with the founding of the United States. The leaders included an icon of rectitude, George Washington; brilliant thinkers such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison; men of vision and passion, including Samuel and John Adams; and a sage conciliator, Benjamin Franklin. Likewise, the founders of the Internet precursor ARPANET included visionaries such as J.C.R Licklider, crisp decision-making engineers such as Larry Roberts, politically adroit people handlers such as Bob Taylor, and collaborative oarsmen such as Steve Crocker and Vint Cerf.

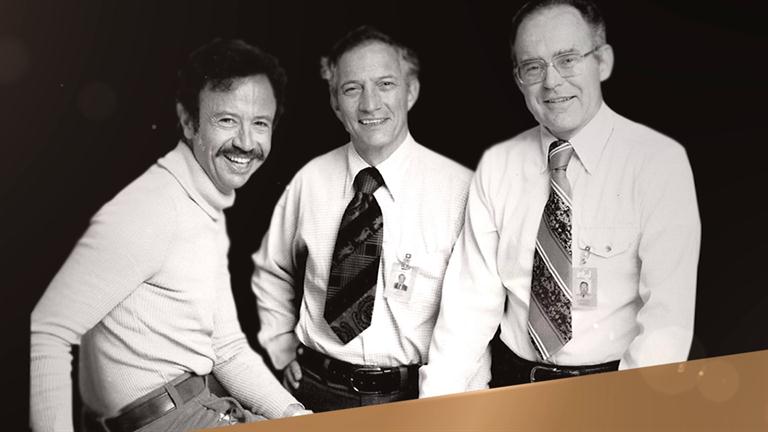

Another key to fielding a great team was pairing visionaries, who can generate ideas, with operating managers, who can execute them. Visions without execution are hallucinations. Intel’s Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore were both visionaries, which is why it was important that their first hire at Intel was Andy Grove, who knew how to impose management procedures, force people to focus, and get things done.

Visionaries who lack such teams around them often go down in history as merely footnotes. There is a lingering historical debate over who most deserves to be dubbed the inventor of the electronic digital computer: John Atanasoff, a professor who worked almost alone at Iowa State, or the team led by John Mauchly and Presper Eckert at the University of Pennsylvania. In this book I give more credit to members of the latter group, partly because they were able to get their machine – ENIAC – up and running and solving problems. They did so with the help of dozens of engineers and mechanics plus a cadre of women who handled programming duties. Atanasoff’s machine, by contrast, ended up not fully working, partly because there was no one to help him figure out how to make his punch card burner operate. It ended up being consigned to a basement, then discarded when no one could remember exactly what it was.

The most successful endeavors in the digital age were those run by leaders who fostered collaboration while also providing a clear vision. Too often these are seen as conflicting traits: a leader is either very inclusive or a passionate visionary. But the best leaders could be both. Noyce was a good example. He and Moore drove Intel forward based on a sharp vision of where semiconductor technology was heading, and they both were collegial and non-authoritarian to a fault. Even Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, with all of their prickly intensity, knew how to build strong teams around them and inspire loyalty.