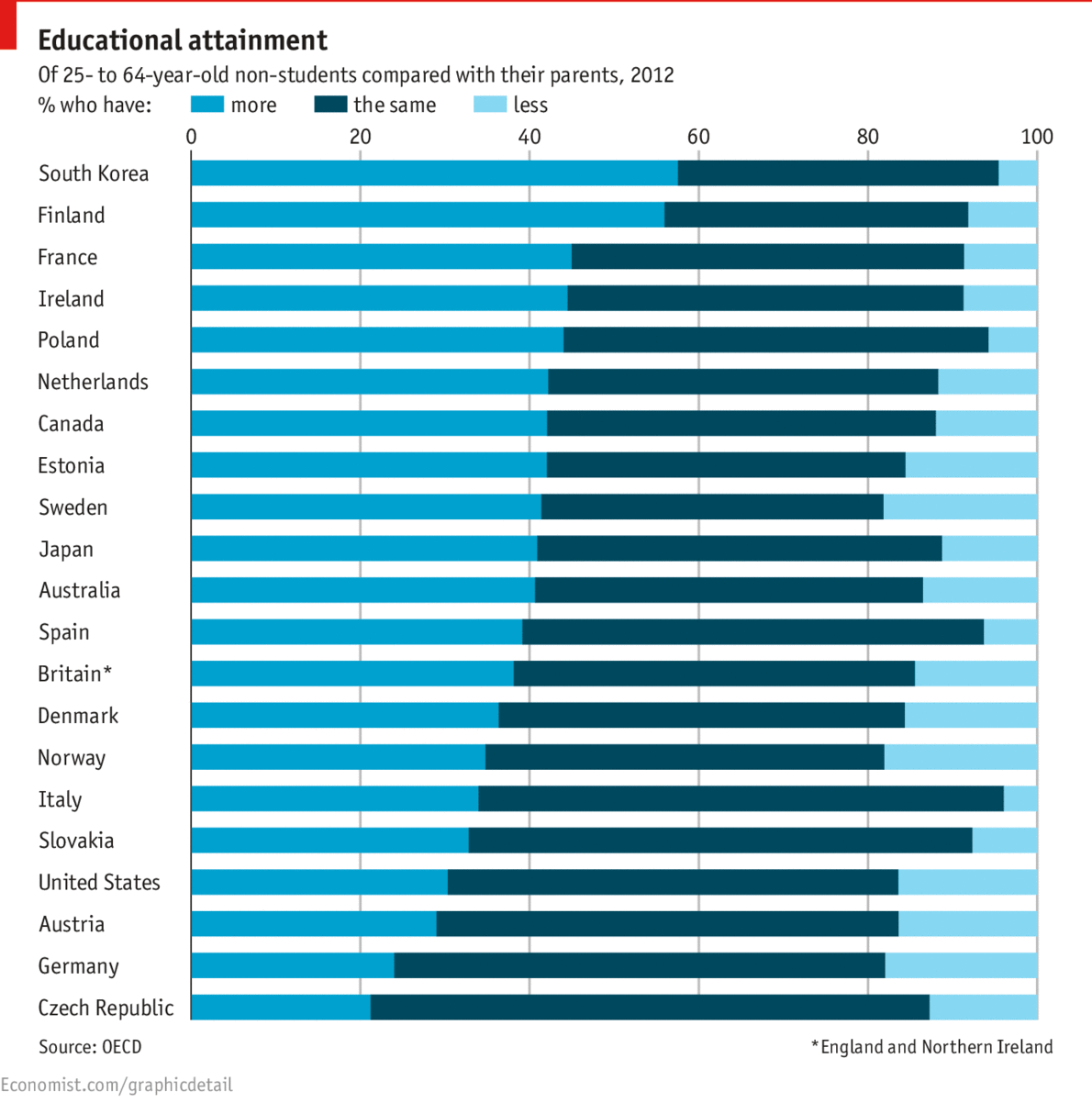

How kids compare against their parents’ level of schooling

SOCIAL mobility, or the lack of it, gnaws at the consciences of governments. Better opportunities for those born without the local equivalent of a silver spoon in the mouth is a common electoral promise. Some recent data suggest it is hard to deliver.

The OECD’s latest "Education at a Glance" report compares how well rich countries are faring in spreading educational opportunity, by ranking countries according to the proportion of 25- to 64-year-olds who are better educated than their parents. A striking feature is a strong correlation of socially mobile countries at the top of the table with excellent test results in secondary schools (as measured by the OECD’s regular PISA tests and others). So South Korea heads the education-mobility league, just ahead of Finland. Both have been consistently high in the rankings for student performance too.

Below that though, things become perplexing. Although they lag significantly behind the stars, France and Ireland score highly. Moreover France, the Netherlands and Poland fare well in terms of opportunity, though their educational performances differ: Poland and the Netherlands receive strong marks in PISA; France less so. Though France has lots of graduates from elite universities whose parents are also well educated, it is adept at pushing able pupils into good-quality technical schools—which may explain its high educational mobility.

At the bottom end of the table, there is bad news for Germany. It shows a low level of upward mobility—about the same as the Czech Republic’s. But because many Germans match their parents’ level of education, this may explain why they are not more anxious about being Europe’s social mobility laggards. As for Britain, where the topic is a staple of political debate, it sits below the chart’s average.

America’s reputation as the land of opportunity looks frayed too, with low upward movement in terms of schooling and high downward mobility. A worrying factor overall, says Andreas Schleicher, who runs PISA, is that the "expansion of higher education has often failed to produce greater social mobility". Working out why and what to do about it is the next big challenge from Berlin to Boston and beyond.