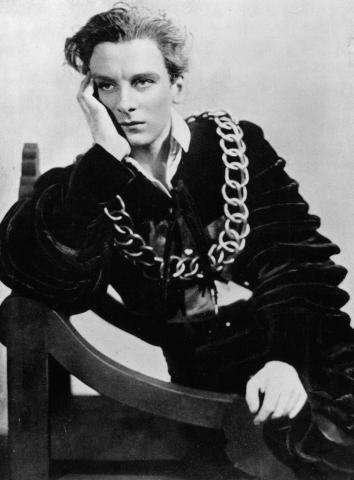

Photo by Johan Persson/Barbican Theatre

Picture for a moment Hamlet, the melancholy prince of Denmark. Chances are, you’re imagining a dashing gentleman who looks like one of the many famous actors who’ve played him. Kenneth Branagh, say, or Laurence Olivier, or Jude Law or David Tennant. You might even picture Benedict Cumberbatch, who is drawing crowds to London to see him play the role. As the Guardian’s Michael Billington put it, “Cumberbatch has many of the qualities one looks for in a Hamlet. He has a lean, pensive countenance, a resonant voice, a gift for introspection.”

Billington is right: one does look for a Hamlet that is lean and pensive or, failing that, an action hero like Mel Gibson or Keanu Reeves, who both played the role in the 1990s. Cumberbatch combines aspects of both, having recently played both Sherlock Holmes and a genetically engineered supersoldier in Star Trek: Into Darkness.

But what if our mental image of Hamlet is wrong? What if the grieving, vengeful prince is actually fat? Just because you’ve never considered the possibility doesn’t mean that Shakespeare scholars haven’t argued about it, just one front in a centuries-old debate about how you determine meaning in Shakespeare’s plays.

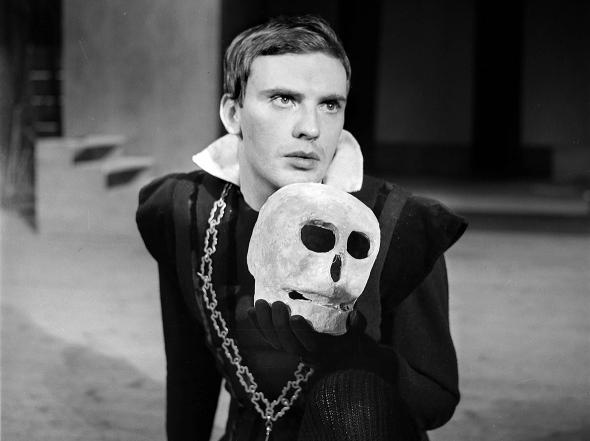

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The most straightforward way to figure out whether Hamlet is fat is to look at the text itself, in which Hamlet’s own mother calls him fat. During the play’s final sword duel, King Claudius turns to Queen Gertrude and says that Hamlet will win the duel, and Gertrude replies, “He’s fat and scant of breath,” before turning to Hamlet and telling him to “take my napkin, rub thy brows.”

Oh, great! you might think. Hamlet’s fat! Someone get Benedict Cumberbatch on the phone and tell him to start pounding the Big Macs. But just when you thought Shakespeare might, for once, make things easy, it turns out this line doesn’t prove anything. For one thing, there is no definitive text of Hamlet. Most versions of Hamlet we see or read are cobbled together from multiple editions, none of which had Shakespeare’s direct involvement. Gertrude’s line about her son being fat and scant of breath, for example, doesn’t appear in the earliest published edition of the play. We’re also not entirely sure where that first edition (called the “first quarto,” or “the bad Hamlet”) came from. It may be a first draft written by Shakespeare, or it could be pirated by an audience member furiously scribbling the play down as it was performed, or reconstructed by one of the actors who played a minor role in the show.

Maybe the line’s absence doesn’t matter. After all, the bad Hamlet is bad. It’s the version of Hamlet where the play’s most famous speech begins, “To be or not to be, aye, there’s the point.” But its absence in an early version could also demonstrate that Shakespeare added the line about Hamlet being “fat and scant of breath” later, as Richard Burbage, the actor playing Hamlet, like so many of us in our late 30s, got a little fat and scant of breath.

Photo by Gordon Anthony/Getty Images

Looking at Burbage—Shakespeare’s leading man and business partner—is another way we can determine if Hamlet is fat. The problem is that we have only one portrait of Burbage, and it dates from later in his life. (He doesn’t look that fat.) We know from a funeral elegy that Burbage’s “stature” was “small,” but although there’s a tradition that holds that he was somewhere between 14 and 17 stone (200-240 pounds), there’s no real evidence that this is true. Some scholars feel Julius Caesar might hold a clue; Burbage almost certainly played Brutus and Hamlet in the same year, and Caesar famously describes another character as too skinny to be trusted, implying perhaps that Brutus, on the other hand, isn’t skinny. At this point, though, we’re grasping at the leanest and hungriest of straws.

We can also look at the history of scholarship of Hamlet, as University of Wisconsin–Whitewater professor Elena Levy-Navarro does in this wonderful essay on the subject of Hamlet’s fatness. Levy-Navarro documents how, during the Victorian era—a time of fad diets and fitness crazes where one’s weight was mistaken for an indication of one’s moral fiber—a vocal minority of Shakespeare scholars, following the lead of Goethe, believed Hamlet was fat and that his fatness indicated weakness. A Victorian actor named E. Vale Blake declared in an 1880 article for Popular Science Monthly that Hamlet was “imprisoned in walls of adipose,” which, “essentially weakens and impedes … the will,” leading to his inability to, as Levy-Navarro puts it, “act decisively to avenge his father.”

We also live in a time of fad diets and fitness crazes where one’s weight is mistaken for an indication of one’s moral fiber. Today, however, Hamlet’s heroism is taken for granted, and very few people believe that the text of Hamlet definitively shows he is fat. According to Levy-Navarro, some scholars claim “the word must be a printer’s error. Shakespeare must have written ‘hot,’ ‘faint,’ or ‘fey.’ ” Plumbing the depths of Shakespearean listservs, we find similar arguments. Harvard’s Eric Johnson-DeBaufre suggested, for example, that “ ‘fat’ is Shakespeare’s truncation of ‘fatigate,’ an adjective [meaning weary] in regular use during the period,” including in texts Shakespeare likely read.

Even if it’s not a printer’s error or a truncation, fat might not mean what we think it means. In Elizabethan times, fat also meant sweaty. Since Gertrude offers Hamlet her napkin to wipe his face, perhaps context reveals that fat refers to his perspiring brow. This begs the question: How can anyone ever definitively say what the meaning of a word is in Shakespeare?

I decided to get to the bottom of this with some help from John-Paul Spiro, a Shakespearean scholar who teaches at Villanova. According to Spiro, investigating the meaning of specific words in Shakespeare is particularly fraught because Shakespeare was the Ornette Coleman of language. Beyond inventing more than 1,700 words, Shakespeare was “deliberately coming up with new meanings of words, and opening up new conceptual spaces,” Spiro said. The play Macbeth invents the contemporary definition of the word success, for example, and Shakespeare was the first person to use crown as a verb.

In order to figure out what fat means at this specific moment of Hamlet, then, we must look not only at how Elizabethans understood the term, but how his contemporaries used the term, how Shakespeare uses it in his plays in general, and how Shakespeare uses it in Hamlet. To the Elizabethans, fat could indeed mean sweaty, but “sweaty in the way fatty meat is sweaty when you cook it,” Spiro said. “Even in Elizabethan times, you would never say, ‘I went for a run, and now I’m fat.’ ”

Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images

But how did Shakespeare use it? At my urging, Spiro dug out his concordance and looked up every single usage of the word fat in Shakespeare. Of the 80 or so times Shakespeare uses fat, there are two usages outside of Hamlet where the Bard could be referring to sweat, but in general “ ‘stuffed’ is really what it’s used to mean,” Spiro told me. “Not just heavy. Overfull, teeming, something fatted and overfed, like livestock.”

It has other connotations as well, particularly around clumsiness. “If you have a fatted goose, it’s not going to walk well,” he says. “If you go back to references to Falstaff and a few other characters, there’s also a hint of calling someone effeminate. You’re clumsy the way a very pregnant woman is clumsy.”

In Hamlet itself, fat is used in ways that reference fullness and death. Fat appears first in Act I, when the Ghost tells Hamlet that if he is not interested in the Ghost’s story, he will be “duller … than the fat weed/ That roots itself in ease,” on the banks of the river Lethe, which cleansed newly dead souls of their memory in Greek myth. In the Queen’s bedchamber scene, Hamlet expresses his horror at his mother sleeping with her husband’s brother/murderer, ranting, “forgive my this my virtue/ For in the fatness of these pursy times/ Virtue itself of vice must pardon beg.” Hamlet is declaring Denmark so stuffed with corruption that virtue is subservient to vice.

Photo by Roger Viollet/Lipnitzki/Getty Images

The most explicit linkage of the word fat with both fullness and death comes in Act IV. When Claudius asks Hamlet—who has just murdered Polonius—where Polonius is, Hamlet responds that he is currently being eaten by worms, before saying:

Your worm is your only emperor for diet: we fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots: your fat king and your lean beggar is but variable service, two dishes, but to one table: that's the end.

Here we see Shakespeare’s joy in multiple meanings on glorious display, using fat as both adjective and verb to describe a grimly comic circle of life in which everything and everyone is doomed and, in a worm’s belly, equal.

Less than an hour later instage time, Gertrude’s line about Hamlet’s fatness appears. According to Spiro, Hamlet’s use of the word in Act IV and Gertrude’s in Act V are connected. Claudius says that Hamlet will win, and Gertrude replies, in essence: “Look at him, he’s heavy, he’s not moving well, he’s already out of breath, he’s going to get carved up.” This line both recalls for the listener Hamlet’s speech about death and paves the way for Hamlet’s own demise. This link doesn’t work unless fat carries with it the connotations of overfull livestock about to die.

So most of the evidence indicates that when Gertrude uses the word fat referencing Hamlet, she means, well, fat. There’s even additional—although, of course, ambiguous—evidence elsewhere in the play that Hamlet is fat. Ophelia, who gives the most detailed physical description of Hamlet in the play, talks about a sigh “shatter[ing] all his bulk” while he’s pretending to be mad. The word bulk is used elsewhere by Laertes when he describes Hamlet’s love for Ophelia waxing and waning like the moon in its bulk. Yet not only is Hamlet’s fatness a minority position within Shakespeare studies, but in the past 15 years, only two high-profile productions of Hamlet—one with Simon Russell Beale, the other Paul Giamatti—have starred actors who weren’t svelte. Perhaps the more pertinent question, then, is why we assume—or even need—Hamlet to be thin.

Photo by Richard A. Brooks/AFP/Getty Images

Shakespeare performance and study, of course, relies on tradition in the absence of primary sources. As Spiro put it in our interview, “Most of what we ‘know’ about Shakespeare comes from a couple of centuries after his death.” Our traditional idea of what Hamlet is like—thin, melancholy, a bit dashing, like an Oedipally fixated sexy Ph.D. candidate—is at this point bolstered by both centuries of questionable scholarship and a long line of memorable performances on stage, television, and film.

There’s a darker underbelly here, however. In the age of the gym body, we expect our heroes to look like this. Hamlet gets to romance (and doom) a young woman, and kill people, and escape from pirates, and think deep thoughts about life and death, and recite gorgeous poetry, and die in the midst of a spectacular sword duel. At no point in any of this is his fatness a source of pain or mocked the way that, say, Falstaff is mocked.

These two problems reinforce each other. Tradition holds that Hamlet is lean and pensive; this jibes with our ideas of what a hero is and feels right; the tradition is then bolstered further. Reviews of both Beale’s and Giamatti’s performances, for example, tended to mention their unconventional bodies, with the Boston Globe’s Don Aucoin noting that Giamatti’s age, height and “paunch” made him “far from the heroically dashing Laurence Olivier model of the melancholy Dane.”* An interview from the time of Beale’s Hamlet reveals how the actor’s body shaped his career, confining him to both the stage and comic roles at the beginning of his career while contemporaries like Ralph Fiennes decamped for Hollywood. The only way to break this cycle is to create a counter-tradition of overweight Hamlets, opening up the role to actors we would not have normally considered. Some lean actors will be disappointed, I’m sure. But they can comfort themselves knowing that nearly every other leading role ever written was made for them.

*Correction, Sept. 21, 2015: This article originally misidentified the Boston Globe critic who reviewed Hamlet, starring Paul Giamatti, as Dan Aucoin. It was Don Aucoin.