演藝, 팻션

The Best Movies of 2018 (So Far),,,이창동 감독의 "버닝"이 18위

The Best Movies of 2018 (So Far)

From the multiplex to the art house, here are the year's standout films.

Cinephilia is a year-round condition, and thus it’s always an ideal time to honor the best of the current movie crop. Now nearing the end of 2018, a wide range of stellar offerings have illustrated that, no matter the genre, potential greatness abounds at both the multiplex and the art house. With seasons to go until the calendar once again turns, this rundown will undoubtedly transform in a variety of unexpected ways before reaching its final form in December—a situation almost guaranteed by the fact that works from the likes of Alfonso Cuarón, Robert Zemeckis, and Barry Jenkins are still on their way. Nonetheless, at present, these are our picks for the best movies of 2018.

In the bleak, barren Outback circa 1929, an Aboriginal man named Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris) finds himself on the run from pursuers—with his wife in tow— after he kills a nasty white man in self-defense. Dramatized without musical accompaniment, Warwick Thornton’s gripping and gorgeous Australian Western recounts Sam’s fictional ordeal with potent authenticity, his feel for the hardscrabble region and its legacy of violence and bigotry doing much to infuse the action with rugged life.

As a preacher with Sam’s best interests at heart, Sam Neill is his usually magnetic, compelling self, while Bryan Brown brings complex determination to his role as a military sergeant tasked with tracking Sam down. Most powerful of all, though, is the standout performance of Morris, who with minimal words and slight gestures—a nod of the head, a shift in body weight, an expression of closed-eyes resignation or defiance—conveys the immense toll of ingrained historic prejudice on an individual’s, and a nation’s, soul.

As energized as anything he’s made in years, Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman tackles our current white nationalist-stained era via the based-on-real-events tale of 1970s African-American rookie undercover detective Ron Stallworth (John David Washington), who infiltrates the KKK with the aid of Jewish partner Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver). Lee has a tendency to let scenes run on long after their point (and impact) has been made, yet here, that habit rarely undercuts the electricity of his action, which has Stallworth and Zimmerman posing as a racist white man (the former on the phone, the latter in person) to gain the confidence of the Klan and its leader, David Duke (Topher Grace)—all as Stallworth develops a less-than-upfront relationship with an African-American activist (Laura Harrier).

Concerned with issues of intolerance and identity (and what it takes to “pass” in particular societies), rife with current-events parallels, and canny about its own place in cinema history (and movies’ effect on the national discourse), it’s amusing, suspenseful, and intensely engaged with the present moment

Few exploitation-cinema subgenres are as durable (and problematic) as the rape-revenge fantasy, and French writer-director Coralie Fargeat’s contribution to that group has a fierce vitality and self-conscious sense of humor that invigorates its familiar premise. In a vast desert, a married man’s (Kevin Janssens) sexy young mistress (Matilda Lutz) is sexually assaulted by one of his two visiting friends; when she subsequently flees, they attempt to kill her, albeit unsuccessfully.

That instigates a game of cat-and-mouse in the vast, arid middle of nowhere, which Fargeat stages with extreme stylishness, whether it’s close-ups of gushing wounded flesh or a dream-within-a-dream-within-a-hallucination sequence that underlines her playful attitude toward the proceedings. Refusing to revel in its heroine’s torment, indulging in over-the-top symbolism, and delivering action set pieces that are equally thrilling and goofy—including a mountain-road showdown and climactic single-take pursuit that confirm Fargeat’s formal dexterity—it proves a righteously wicked midnight movie for the #MeToo era.

Green Room director Jeremy Saulnier once again pits men against each another in a hostile environment in Hold the Dark, a frost-bitten clash between the modern and the ancient. In a remote Alaskan town, a woman (Riley Keough) claims that her son has been snatched by wolves, and calls upon an author (Jeffrey Wright) with considerable experience living amongst the creatures to find the kid. The writer’s search soon takes a turn for the twisted, and then for the deadly, once Keough’s mom goes AWOL and her husband (Alexander Skarsgard) returns from overseas military duty, a look of cold, amoral ruthlessness in his eyes.

These characters’ ensuing game of hunt-or-be-hunted is cast in bleak shadows and blinding whites by Saulnier, whose serpentine camerawork augments his panoramas of grief, isolation, misery and viciousness. Complemented by a terrifying Skarsgard and mysterious Keough, Wright delivers a performance of quiet, complex intensity that reconfirms his status as one of cinema’s premiere actors.

In Zambia, women are still accused of being witches—and then sent to live in camps, forced to perform manual labor, and (most stunning of all) compelled to preside over criminal trials, where they’re supposed to use their supernatural powers to make judgments. This insane real-life scenario is brought to bleakly satiric life by I Am Not a Witch, Rungano Nyoni’s directorial debut about a young girl dubbed Shula (Maggie Mulubwa) whose world is turned upside-down after authorities determine she’s a witch.

Under the guidance of government official Mr. Banda (Henry B.J. Phiri), Shula embarks on an odyssey that’s littered with indignities and absurdities, including appearing on a TV talk show where she’s asked to hawk magic “Shula eggs” to the audience like some infomercial huckster. Set to an eclectic score (sharp strings, harsh noise) that’s sometimes at odds with the action, Nyoni’s drama—playing like a droll, horrifying 21st century riff on The Crucible—is a startlingly inventive story about modern institutionalized misogyny.

Tom Cruise risks life and limb—literally, in many instances—for his sixth go-round as Ethan Hunt in Mission: Impossible – Fallout, the finest action film since 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road. In writer/director Christopher McQuarrie’s adrenalized espionage thriller, Hunt is tasked with recovering a trio of plutonium cores while juggling his relationships with colleagues (Simon Pegg, Ving Rhames, Alec Baldwin), alluring spy Ilsa Faust (Rebecca Ferguson), and former wife Julia (Michelle Monaghan)—not to mention CIA-assigned assassin August Walker (Henry Cavill), who has orders to kill Hunt should he stray from his assignment.

That intertwining of the personal and professional provides a sturdy backbone for a series of set pieces that, especially in IMAX, are nothing short of astonishing, as McQuarrie begins with a slam-bang bathroom brawl and then continually ups the eye-opening ante, culminating with an aerial showdown between Hunt and Walker aboard helicopters that establishes Cruise, and the series, as the reigning kings of Hollywood spectacle.

In 1917, the sheriff of Bisbee, Arizona—a remote mountain-nestled enclave then known for its wealth of copper—rounded up the town’s striking German and Mexican miners and, with the aid of a 2,000-man posse, took them out to the desert and left them there, never to be seen or thought about again. Robert Greene’s daring and accomplished Bisbee '17 refuses to consign those unjustly persecuted victims to the forgotten realms of history, instead using traditional documentary footage and dramatic reenactments—often taking the surprising form of musical numbers—to revisit that calamitous event.

As in his prior Actress and Kate Plays Christine, Greene’s blending of fiction and non-fiction techniques is assured, and results in an insightful investigation into race relations, class conflicts, and the nature of memory. A mournful ghost story that doubles as an act of resurrection and reclamation, it’s a saga about past crimes with undeniable present relevance.

The angry disaffection of South Korean youth, and the sinister trouble it can breed, is the focus of Lee Chang-dong’s Burning, which melds suspense and social commentary to eerie effect. Jong-su (Ah-in Yoo) is a delivery boy whose heart is enflamed after a run-in with beautiful Haemi (Jong-seo Jun), a former classmate he can’t remember. After having Jong-su catsit for her while she visits Africa, Haemi returns with a new friend in tow—wealthy, suave Ben (Steven Yuen), whose intrusion into their budding romance frustrates the jealous Jong-su.

While that set-up suggests a love triangle drama, what ensues is something far more beguiling, as Haemi goes missing and Ben expounds on his fondness for setting rural greenhouses on fire. Thrust into the role of detective, Jong-su searches for Haemi but, as with her cat (which is never seen), he finds few answers to his questions about anyone, or anything. Led by exceptional turns by Yoo and Yuen, Lee’s latest is an ambiguous examination of class, envy and the unknowable mysteries of the world.

Eight years after her last fictional feature (2010’s Winter’s Bone) introduced the world to Jennifer Lawrence, writer-director Debra Granik returns with Leave No Trace, a pensive, thorny character study about a father (Ben Foster) and daughter (newcomer Thomasin McKenzie) illegally living off the grid in the national forests of the Pacific Northwest.

Once again teaming with co-screenwriter Anne Rosellini and cinematographer Michael McDonough (this time on an adaptation of Peter Rock’s novel My Abandonment), Granik details the ins and outs of her characters’ isolated circumstances while plumbing the trauma that’s driven Foster’s dad to retreat from society—and the tension that develops between him and his daughter, who finds it difficult to assume her father’s grievances (and, thus, lifestyle). There’s no judgment here, just empathetic curiosity about unique lives situated on society’s fringe—as well as some fantastic acting from a silently tormented Foster and a confused and brave McKenzie in a sterling debut performance.

Can a man change his malevolent ways—and, more difficult still, manage to help a loved one do likewise? Such is the question at the heart of The Sisters Brothers, an eccentric and disarming Western from director Jacques Audiard (A Prophet) about two assassins (Charlie, played by Joaquin Phoenix, and Eli Sisters, played by John C. Reilly) ordered by their boss (Rutger Hauer) to track down a chemist (Riz Ahmed) with the assistance of a detective (Jake Gyllenhaal).

That phenomenal foursome is led by Reilly in a career-best performance as a killer caught between loyalty to his merciless sibling and a personal desire to forever holster his six-shooters in favor of a more cultivated existence (here epitomized by his experimentations with a toothbrush). Adapted from Patrick deWitt’s novel, the film segues between no-nonsense action, dry comedy, and lyrical drama, all of which is expertly rooted in the tension—both individual and national—between the civilized and the wild.

Thai prisons are best avoided at all costs, and Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire’s adaptation of Billy Moore’s autobiography is disturbing proof of that fact. After a life of selling (and abusing) drugs lands him in the notorious “Bangkok Hilton,” boxer Moore (Joe Cole) struggles to survive a new world for which he’s not prepared. Acts of rape and violence are omnipresent in this ramshackle environment, which Sauvaire brings to horrifying life through blistering handheld cinematography and equally jarring sound design, replete with Thai dialogue that’s left un-subtitled for maximum disorientation.

Tracing Moore’s rocky path from wanton self-destruction to uneasy transcendence, the film is as unsentimental as it is brutal, especially in its pugilistic sequences, which the director shoots with an astounding measure of up-close-and-personal viciousness and an apparent lack of choreography, as combatants wail on each other with reckless abandon. Cole’s go-for-broke performance as this out-of-control man—all crazy-eyed desolation and battering-ram physicality—is the stuff that turns actors into stars.

Indie directors Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead’s first two features, 2012’s Resolution and 2014’s Spring, were an idiosyncratic blend of indie character drama and supernatural menace and madness. That mix is even more apparent in their excellent third feature, which charts the odyssey of two brothers (played by Benson and Moorhead) as they make a return visit to the remote California UFO sex cult that they first fled—under controversial, and headline-making, circumstances—years earlier.

Existing in the same fictional cine-verse as their low-budget debut, The Endless generates unease, and then dawning terror, from its raft of beguiling mysteries, which, from a simple starting point, spiral outward in an increasingly all-consuming manner. Yet no matter its gradual descent into unreal terrain, its primary focus remains the fraught relationship between its sibling protagonists, whose push-pull rapport is central to the film’s overarching, and affecting, examination of conformity, rebellion, and the insidious cycles (of thought, and behavior) that threaten to trap us where we stand.

A superior slice of children’s entertainment, Paul King’s sequel to 2015’s Paddington is a sheer joy, infused with comic inspiration and irresistible sweetness. In this second series installment based on the stories of author Michael Bond, the perpetually hatted Paddington (voiced by Ben Wishaw) winds up in prison after he’s framed for the theft of an elaborate pop-up book that he planned to purchase for his dear Aunt Lucy (Imelda Staunton)—a crime that’s actually been perpetrated by a faded local actor (and master of disguise) played to cartoonish perfection by Hugh Grant.

The set pieces are uniformly inventive, the hybrid live-action/CGI aesthetics are superb, and the supporting cast—including Sally Hawkins, Brendan Gleeson, Julie Walters, Jim Broadbent, and Peter Capaldi—is across-the-board fantastic. only the hardest of hearts could resist its good-natured charm, epitomized by its sincere belief (advocated by Paddington himself) that the key to improving the world (and ourselves) is compassion, affection, politeness, and positivity.

Thunder Road begins with a ten-minute single-take scene of such cringe-worthy humor and wrenching pathos that it’s a borderline miracle the film manages to live up to it. That it certainly does, as writer-director-star Jim Cummings’s first feature deftly navigates the uneasy tragicomic territory inhabited by its main character, Texas police officer Jim Arnaud. Reeling from the death of his mother (whose funeral is the setting for the aforementioned opener), and coping with an impending divorce from his ex (Jocelyn DeBoer) and the cold-shoulder treatment from his fourth-grader daughter (Kendal Farr), Jim begins to lose it both at home and at work, this despite the best efforts of his compassionate partner (Nican Robinson).

Cummings’ expertly calibrated turn moves between heartbreaking and absurd at a moment’s notice, providing an unvarnished snapshot of one angry, unstable but good-natured man’s grief-stricken disintegration. It’s a film that knows what it’s like to feel as if your world is falling apart, and the difficulty of making it—and yourself, and your family—whole again.

Leon Vitali delivered a star-making turn as Lord Bullingdon in Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 period-piece Barry Lyndon. After that performance, however, the actor opted to become his director’s right-hand man—a position he would hold until Kubrick’s death in 1999. Filmworker, Tony Zierra’s outstanding documentary about Vitali, is a portrait of a man who subsumed his own priorities and personality in order to be whatever his employer required, which in this case included operating as an acting coach, a script supervisor, an exacting technician, and an advertising manager.

A study of obsessive devotion and self-destruction, Zierra’s film conveys the round-the-clock arduousness of assisting a perfectionist like Kubrick, and the toll such employment took on Vitali’s health and relationship with his family. Now an apprentice without a master, Vitali proves a complex figure of commitment taken to a crazy extreme—as well as a charismatic artist in his own right, whose recognition for the work he did alongside the 2001 and The Shining auteur remains long overdue.

Teenagerdom is tough, and Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade captures the difficult ups and downs of that universal experience with amusing and moving realism. Elsie Fisher is a revelation as thirteen-year-old Kayla, whose day-to-day existence on the cusp of middle school graduation is defined by social media, squabbles with her single dad (Josh Hamilton), and social anxiety and ostracism.

Burnham’s plot is littered with specific bits that anyone who is (or is living with someone) this age will recognize as spot-on (“LeBron James!”). More compelling still is his depiction of social media’s role in kids’ process of self-definition, of girls’ awkward and often unpleasant first forays into romantic and sexual territory, and of the peer pressure-created insecurities that complicate one’s maturation (and relationship with parents). Unvarnished to the point of sometimes being outright cringe-worthy, it recognizes how tough it is to figure out who you are—and locates hope in the knowledge that that process continues long after you’ve moved on to high school.

Rosamund Pike gives the performance of the year in A Private War, exuding a complex mixture of fierce determination and PTSD-fueled torment as real-life war correspondent Marie Colvin, who perished during Syria’s Siege of Homs in 2012. Directed by Matthew Heineman (Cartel Land, City of Ghosts), this jagged, riveting drama details the acclaimed career of Colvin, whose fearless expeditions to global hot-spots to capture the human face of war took an immense toll on her psyche.

Donning the reporter’s signature eye patch and speaking in her gravelly voice, Pike brilliantly evokes the messy contradictions of Colvin’s life—her bravery, her instability, and her dogged desire to make people care about the world’s horrors as much as she did. Her performance is matched by the direction of Heineman, who employs a fractured editorial structure and tragic up-close-and-personal warfare imagery in order to carry on Colvin’s mission of making the political deeply personal. In an age in which the media is under increasing attack, it’s a bracing and timely portrait of journalistic courage and sacrifice.

Before passing away in 2016 at the age of 76, Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami completed work on this, his final film, an experimental documentary that serves as a melancholy meditation on mortality and the moving image. As original as it is striking, 24 Frames features twenty-four scenes, each containing a still photograph taken by Kiarostami (save for the opening shot of Pieter Bruegel’s 1565 painting The Hunters in the Snow) that then slowly comes to animated life courtesy of sly digital effects that cause animals to run, clouds to roll by, and smoke to billow from chimneys. By lingering on each of these sights as they spring into action, the director situates viewers in a trancelike realm.

While no overt commentary is provided, the repetition of objects, figures and rhythms soon impart the project’s underlying fascination with issues of loneliness, compassion, romance, and the inexorable forward march of time—a subject that, in the end, reveals Kiarostami’s swan song as a moving treatise on his, and mankind’s, fundamental impermanence.

Ten years after The Headless Woman, Argentinean director Lucrecia Martel returns with another mesmeric reverie—Zama, an adaptation of Antonio di Benedetto’s 1956 novel about an 18th century Spanish official, Don Diego de Zama (Daniel Giménez Cacho), stuck in a Paraguay River outpost from which he cannot escape. Awash in existential doubt and despair, Zama tends to mundane magisterial tasks, flirts with a noblewoman (Lola Dueñas), and vainly requests transfer back home to see his wife and kids—the last of which is pointedly, and hilariously, dramatized during a scene in which a llama wanders into the frame behind Zama, accentuating his absurdity.

Cinematographer Rui Poças’ exquisitely framed imagery, and Guido Berenblum’s arresting natural-noises sound design, lend unreal beauty to the first half’s series of go-nowhere bureaucratic and personal encounters, which underline the protagonist’s purgatorial condition as well as the prejudiced power dynamics that serve as this new society’s foundation. A finale in which Zama takes action then transforms the film into a nightmare of confusion, alienation, and futility.

It’s been forty-two years since Taxi Driver first verified Paul Schrader’s greatness, and with First Reformed, the writer-director provides a magnificent companion piece to that earlier triumph. Also indebted to Robert Bresson, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Ingmar Bergman, Schrader’s religious drama (shot in a boxy 1.37:1 aspect ratio) fixates on Reverend Toller (Ethan Hawke), an upstate New York man of the cloth whose ongoing crisis-of-faith is accelerated by an encounter with an environmental activist beset by hopelessness and anger.

Toller’s ensuing relationship with that man’s wife (Amanda Seyfried), as well as the leader of a local mega-church (Cedric the Entertainer), forms the basis of Schrader’s rigorously ascetic—and occasionally expressionistic—film, which is guided by Toller’s journal-entry narration about his fears and doubts. Formally exquisite and led by a tremendous performance from Hawke as a Travis Bickle-like country priest who can’t quell the darkness within, it’s a spiritual inquiry made harrowing by both its mounting misery and its climactic ambiguity.

The West is wild to its core in Chloé Zhao’s The Rider, a stunning verité drama about a young rodeo star facing an uncertain future after a catastrophic accident. Zhao amalgamates fact and fiction for her sophomore behind-the-camera effort, as her story is based, in part, on the life of actor Brady Jandreau (here cast alongside his own relatives and acquaintances in his native South Dakota). That life-art marriage lends bracing potency to this ode to frontier existence, as does the quiet magnetism of its twenty-something lead.

Nonetheless, the material is truly enlivened by the director’s artful aesthetics, which balance intimate close-ups and at-a-remove panoramas of solitary figures set against expansive rural landscapes—never more so than in a late oncoming-storm shot that could double as an Old West painting. Meanwhile, multiple sequences in which Jandreau trains stallions provide a powerful, tactile sense of communion between man and beast, and in doing so, silently evoke the warring emotions battling for supremacy in the young bronco rider’s soul.

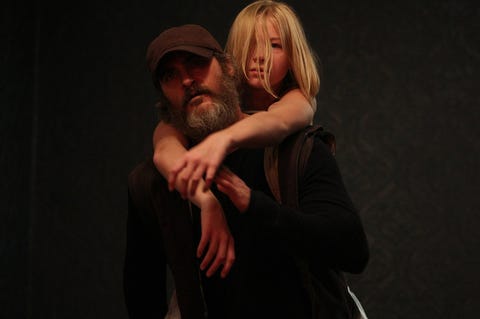

Joaquin Phoenix reconfirms his status as his generation’s finest leading man with You Were Never Really Here, a startling drama that cares less for straightforward thrills than for penetrating psychological intensity.

Barreling forward with both urgent momentum and fragmented lyricism (thanks to oblique edits and jarring flashbacks), the latest from Scottish auteur Lynne Ramsay (Ratcatcher, We Need to Talk About Kevin) tracks a mentally scarred war vet (Phoenix) as he tries to rescue a senator’s young daughter from a child prostitution ring. There’s plenty of bloodshed throughout that underworld quest, yet Ramsay’s treatment of violence is anything but exploitative; rather, her masterful film resounds as a lament for the trauma of childhood abuse, which lingers long after adolescence has given way to adulthood.

Reminiscent of Taxi Driver and energized by Phoenix’s magnetic embodiment of masculine suffering and sorrow, it’s a gut-wrenching portrait of a volatile man’s attempts to achieve some measure of solace from his inner demons—sometimes via the use of a ball-peen hammer.

The type of mature adult drama that mainstream American cinema rarely produces these days, writer-director Russell Harbaugh’s exceptional debut mires itself in a thicket of barbed emotions. In the wake of her husband’s death, Suzanne (Andie MacDowell) strives to start anew, as does her son Nicholas (Chris O’Dowd)—albeit, in the latter’s case, in ways that are as clumsy as they are ugly. Their concurrent efforts to find a way forward (romantically and otherwise) unfold with fractured grace and beauty, as Harbaugh plumbs profound depths via evocative compositional framing and a seductive editorial structure.

Complications soon pile on top of each other until practically no one is capable of breathing (save for during release-valve outbursts), with a piercing MacDowell and magnetic O’Dowd (in a staggeringly raw performance) digging deeply into their characters’ interior messes. What they ultimately discover are alternately unpleasant and inspiring truths about what we do—and what it takes—to survive in the aftermath of tragedy.

Annihilation is the best sci-fi film in years, a mind-blowing trip into an inscrutable heart of darkness that marks writer-director Alex Garland as one of the genre’s true greats. Desperate to understand what happened to her soldier husband (Oscar Issac) on his last mission, a biologist (Natalie Portman) ventures alongside four comrades (Jennifer Jason Leigh, Tessa Thompson, Gina Rodriguez, Tuva Novotny) into a mysterious, and rapidly growing, hot zone known as the “Shimmer.”

What follows is an unsettling and finally hallucinatory tale of destruction and transformation, division and replication—dynamics that Garland posits as the fundamental building blocks of every aspect of existence, and which fully come to the fore during a climax of such surreal birth-death insanity that it has to be seen to be believed.

Apropos for a story about nature’s endless cycles of synthesis and mutation, it combines elements of numerous predecessors (Apocalypse Now, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stalker, The Thing) to create something wholly, frighteningly unique.

The psychosexual hallucinatory heavy-metal grindhouse revenge saga of your cinematic dreams, Mandy is a midnight movie of mythic madness. Director Panos Cosmatos’s wickedly deviant and humorous follow-up to 2011’s Beyond the Black Rainbow concerns a woodsman named Red (Nicolas Cage) whose wife, Mandy (Andrea Riseborough), is taken hostage at their secluded forest home by cultists led by crazed guru Jeremiah Sand (Linus Roache). In the aftermath of tragedy, Red embarks on a rampage as trippy as it is brutal, as Cosmatos creates a pulpy atmosphere of pulsating LSD-fueled doom and gloom that envelops his protagonist as he descends into ever-more-depraved territory.

Torture, mayhem, and shadowy supernatural fiends factor into this orgiastic pulp, which features—among its many euphorically insane sights—its hero lighting a cigarette from a flaming decapitated head, a boozy bathroom freak-out, and the greatest big-screen chainsaw fight since 1986’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. Hovering over the action like a wide-eyed goth specter, Riseborough proves an enchanting object of black-magic desire. A maniacal Cage is equally transfixing in a turn of fantastical, often silent ferocity that culminates in a triumphant smile designed—like the gonzo film itself—to haunt your nightmares.

Watch Next

John Wayne's Personal Bourbon Is the Perfect Gift for Your Dad

'演藝, 팻션' 카테고리의 다른 글

| BTS is first K-pop act to appear on Bloomberg 50 - UPI (0) | 2018.12.08 |

|---|---|

| 「“K”から世界へ」の舞台裏 ――韓国のコンテンツ戦略 (0) | 2018.12.07 |

| How BTS Is Taking Over the World - TIME Magazine (0) | 2018.10.11 |

| K팝이 아니다, BTS-팝이다! (0) | 2018.09.29 |

| Jane Fonda Is Paying Close Attention (0) | 2018.09.28 |

'演藝, 팻션'의 다른글

- 현재글The Best Movies of 2018 (So Far),,,이창동 감독의 "버닝"이 18위