China’s tried to lure researchers to the mainland for years.

Photographer: Stephen Shaver/BloombergChina’s growing technological prowess in areas such as artificial intelligence is making Washington very nervous. U.S. efforts to fight back, though, could make the problem worse.

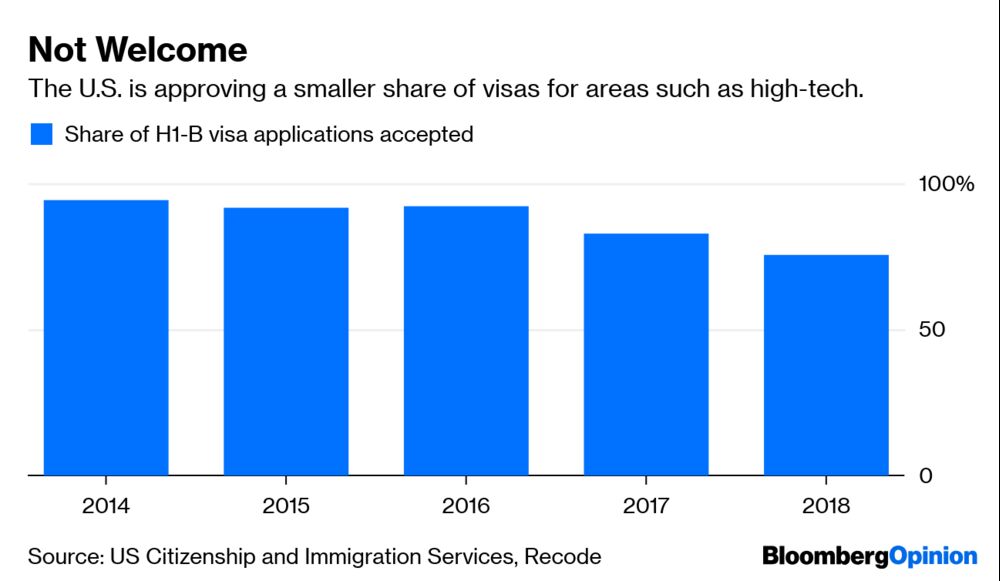

In U.S. policy circles, suspicion of China is starting to resemble a new Red Scare. Universities are heightening scrutiny of research proposals from China and, in some cases, restricting collaboration. Chinese scientists’ visas are being delayed for conferences and exchanges. Visas for Chinese graduate students studying topics such as robotics or advanced manufacturing have been shortened to one year from five.

Last week, the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston kicked out three senior researchers of Chinese ethnicity after the U.S National Institutes of Health said they had potentially violated disclosure and confidentiality rules. Workers at various technology companies have been charged with stealing trade secrets in recent months.

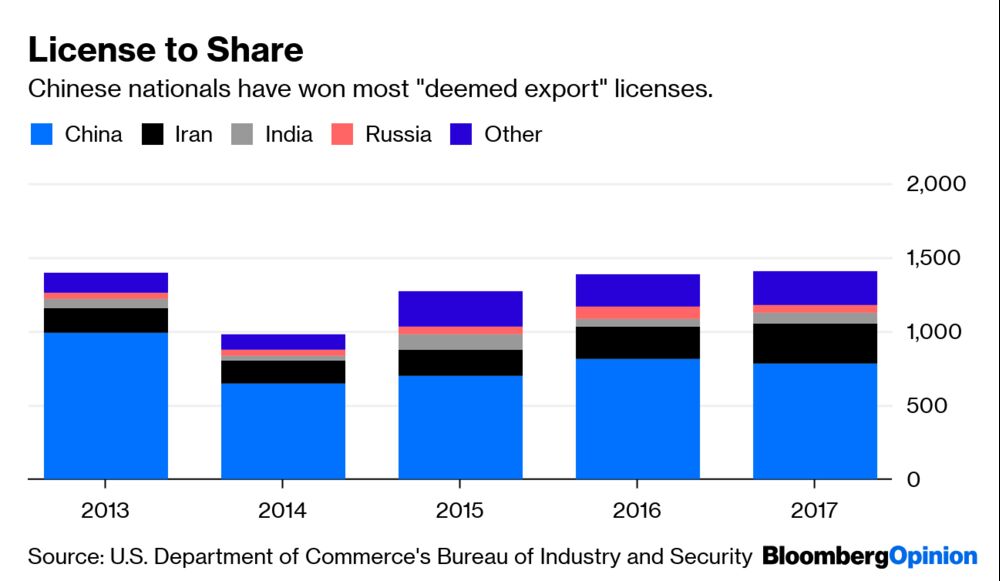

More formal rules are coming. After President Donald Trump signed the Export Control Reform Act last year, the U.S. put in place new policies to restrict Chinese investment in American high-tech companies. It also began a process of reexamining export controls on sensitive “emerging and foundational” technologies. That process is nearly complete: The Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security is holding seminars over the next few months to help companies understand how to comply with the tighter restrictions.

While the details are still murky, one thing is clear about the new rules: Like the old ones, they’ll apply not just to hardware shipped overseas, or even software and algorithms. They will cover individuals and ideas as well.

The disclosure of proprietary information or controlled information to a foreign national, even within the U.S., triggers the need for an export review process. If such an exchange were to happen elsewhere in the world — between a U.S. national and a foreign national — it would be considered an export to that country.

Among other things, this means that U.S. tech companies may not be able to use Chinese researchers to work on certain critical technologies, including AI. The kind of intellectual collaboration that’s produced some of the greatest advances in the field may no longer be possible.

This could be a boon for China. Beijing for years has tried to lure talent to the mainland. It’s set up generous benefits for so-called sea turtles — Chinese nationals who have “swum” abroad to study and work and then returned — from cheap housing to lucrative research grants. Those efforts have had mixed success: Fears of censorship and red tape have dissuaded some; a desire to live and work with the best minds in the world has motivated others to stay on in the U.S.

If new export controls are enforced in their harshest form, the calculus for many Chinese scientists and engineers may change. Their job possibilities in the U.S. will be limited. A potentially cumbersome visa process could discourage many American companies and universities from even interviewing qualified Chinese candidates.

For those who do find work, living under constant suspicion will be far from pleasant. In a letter to Science magazine last month, associations representing Chinese-American scientists said even they fear being singled out and racially profiled.

Some Chinese researchers may seek opportunities in Europe instead, or in countries such as Israel or India with thriving high-tech industries. Many more are likely to go home.

This would drain the U.S. of some of its best talent; institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology rely on foreign students and academics for a significant part of their research capability. It’ll also limit the ability and willingness of U.S. companies and universities to learn from Chinese counterparts: The Commerce Department’s latest “unverified list” — essentially a red flag that requires U.S. companies to do more diligence and provide additional information about a listed company or person, while imposing license requirements — includes mostly Chinese academic institutions, research centers and tech companies.

More conversations will begin taking place outside the U.S. In its global strategy report, MIT noted that “America’s relative economic weight in the world has been declining for decades, and as other countries grow more prosperous, a growing share of global R&D is originating outside the U.S.” Collaborations between Chinese and European researchers will no doubt increase; Washington’s inability to persuade its allies to reject technology from Huawei Technologies Co. has shown the limits of its influence.

When it comes to certain sectors, including artificial intelligence and autonomous vehicles, an influx of new talent now could spur major advances in China. The country already offers some key advantages for researchers — including the reams of data available and fewer privacy concerns. Smart researchers could leverage those tools to leapfrog U.S. technology.

Export controls covering technical information have been around since at least the 1940s. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration also erected barriers to scientific collaboration, fearing Soviet efforts to steal U.S. technology. Universities were pressured to close their doors to foreigners, among other isolationist measures.

Such restrictions ultimately failed to slow the transfer of ideas and technologies. If anything, they blinded the U.S. to its rivals’ growing capabilities. Washington might want to study that history, along with where technology is headed, before isolating itself again.