Rethinking strategy and statecraft for the twenty-first century of complexity: a case for strategic diplomacy

International Affairs, Volume 98, Issue 2, March 2022, Pages 443–469,

https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab212

Abstract

Today's most pressing security and policy challenges—great power conflict, economic interdependence, peacebuilding, climate change and other non-traditional threats such as pandemics—are all complex problems. Hyperconnectivity, power diffusion and radical technological transformation are significantly shrinking the policy space available to governments and other international agencies in what has been called the twenty-first century of complexity. Thus, the practice of statecraft requires accentuated strategic rationale: clear emphasis on big-picture and longer-term purposes and priorities. While effective strategy is essential for mobilizing power and winning strategic contests, effective diplomacy is necessary for garnering support for the strategy. This article contributes to stepping up to this challenge in three innovative ways. First, it utilizes key insights from complex adaptive systems thinking to recast the conceptual underpinnings of power, strategy and statecraft. Second, the article advances a ‘strategic diplomacy’ diagnostic and policy framework to maximize policy space in dealing with complex systems problems in international affairs. And third, by applying the framework to three significant international policy challenges, the article demonstrates the utility and implications of the ‘strategic diplomacy’ framework for strategic policy in the twenty-first century.

Bosh! Stephen said rudely. A man of genius makes no mistakes. His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.

James Joyce, Ulysses (1922), ch. 9, ‘Scylla and Charybdis’

Strategy is ‘the art of creating power’,1 while statecraft is the skill of securing the survival and prosperity of a sovereign state. Statecraft demands the development and execution of strategies in the pursuit of national interests. At the height of the Cold War, the challenge for survival was abundantly clear, given the prospect of mutual assured nuclear destruction. As the American political scientist Morton Kaplan warned in 1952,

the successful or unsuccessful conduct of statecraft may settle the fate of our way of life; and given the possibilities of modern war, it may, in a deeper sense, settle the question of whether any type of civilized life … can survive.2

Today's survival challenges too, have become clear—great power conflict, conventional and nuclear; mutual economic dependence and destruction; climate change and other systemic threats such as pandemics. Strategy and statecraft often appear elusive in the face of these intersecting threats and risks. The Sino-American conflict resists being reduced to war-fighting or zero-sum alliances because of the two countries' deep and broad economic interdependence, and because of the diverse constituencies with active stakes in the relationship. To take another resonant example, national defence against COVID-19 clearly cannot be achieved within a state's borders alone. As corporate strategists have known for some time, approaching these ‘wicked’ problems requires us to be explicit about their complexity and to find ways to operate within this complexity, rather than to persist with policy tools that are not fit for purpose. In international affairs, such issue complexity is compounded by the changing operational environment of statecraft. The world's centre of gravity is shifting from West to East and South, and power is diffusing from state to non-state actors. While diffusion makes power easier to obtain, it also makes it harder to use—and easier to lose.3 Thus the need to develop strategies that are fit for purpose is very urgent indeed.

In this article, we advance a new ‘strategic diplomacy’ conceptual framework and policy tool for strategizing and exercising statecraft in what the late Cambridge theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking called the twenty-first century of complexity. The core problem for governments all around the world is the shrinking policy space caused by hyperconnectivity and power diffusion. Accentuated pluralism, with ‘more actors, more vectors, and more factors’, makes statecraft harder.4 Effective strategy is essential for mobilizing power and winning this strategic contest; and effective statecraft is essential for pursuing and selling this strategy. We argue that our reaction to recognizing complexity ought to be to develop better tools to deal with it, and we contribute to stepping up to this challenge in three ways. First, we use key insights from complex systems thinking to recast the conceptual underpinnings of strategy and statecraft. We argue that managing and harnessing complexity requires a transformative reimagining of strategy and statecraft. Second, we advance the ‘strategic diplomacy’ (SD) diagnostic and policy framework for dealing with such complex systems problems. And third, by applying the framework to three significant international policy challenges, we demonstrate the utility and implications of the SD framework for contemporary strategic policy.

We proceed in four steps. The first section situates strategy and statecraft in the longer history of globalization and the broader context of complex systems thinking. The second section introduces SD as an innovative diagnostic and policy framework. The third section demonstrates how the SD approach can be used to navigate major international challenges within their own complex systems context. We use three case-studies—power competition in Asia; intervention and peacebuilding; and pandemics and COVID-19—to show how SD generates critical leverage by recasting conventional analyses of well-known and debated contemporary strategic problems. The final section highlights implications for twenty-first-century strategy and statecraft.

Rethinking strategy and statecraft in a complex adaptive system

To grapple with the contemporary challenges of strategy and statecraft, we must first diagnose the problem.

Hyperconnectivity

Despite its protean meaning, globalization—understood as ‘the shrinkage of distance but on a large scale’5—captures the condition of accentuated connectivity we are trying to emphasize. Flows of information, ideas, people, goods and services build networks of interdependence among geographically distant units across the globe, transcending the local, national and regional levels. In the language of systems theory, those flows connect multiple nodes and networks, thereby creating a new, interrelated and interacting organism—a system. While globalization and interconnectedness are not new, the scope and intensity of post-twentieth-century globalization are. How to manage, and intervene in, systems in which many actors are so intensely interconnected, interdependent, interacting and adapting to each other, has presented significant policy problems.6

Moreover, connectivity is a double-edged sword. By connecting states and markets, globalization has facilitated economic growth, lifted millions out of poverty and contributed to the exponential rise of the global middle class. Yet connectivity also carries the peril of large-scale disruption across societies, as amply illustrated by historical plagues and pandemics.7 Dating back to Egypt in the third century Bce, smallpox spread across five continents over thousands of years and killed an estimated 300 million people in the twentieth century alone before the World Health Organization officially declared the virus eradicated in 1980.8 More people have been killed by infectious diseases and pandemics—bubonic plague, smallpox and influenza, among others—than by deadly conflict. And yet, while societies have spent considerable effort strategizing, in Clausewitz's words, the employment of battle to achieve the end of war, we have increasingly failed to strategize our way of life under globalization and hyperconnectivity.9

Power diffusion

Globalization and connectivity are not new; we have seen multiple cycles of globalization in the longue durée of global history. In earlier periods, empires—such as that of the Pax Romana (27 Bce–180 Ce)10—often performed the role of ‘globalizers’, pacifying their far-flung possessions with sophisticated combinations of force and inducement. Historically, globalization and integration tended to flourish within stable operational environments created by large concentrations of power. For example, that epitome of globalization, the trans-Eurasian Silk Road, saw its peak during 500–800 Ce, when the Tang dynasty gained control of the central Asian steppes and re-established the Pax Sinica.11 In these earlier periods of globalization, diverse actors and nodes developed to leverage gains from the wider system of flows and exchanges. For instance, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, cosmopolitan ‘port-centred states’ emerged in south-east Asia, which strategically positioned themselves in the expanding trade and production networks of the global economy.12 Similarly, as Fernand Braudel has shown, the Mediterranean world at this historical juncture was embedded in a wider global system of flows and relationships that facilitated the rise of medieval cities, especially in northern Italy, that were the governors and innovators of globalization.13

In contrast, the contemporary world is marked by ongoing shifts of relative power from West to East (and South), as well as the diffusion of power from states to non-state actors.14 Statecraft is no longer the prerogative of developed or western nation-states. The post-1945 global governance architecture was built around US hegemony and held together by a ‘thin’ version of multilateralism that included the industrialized global North but not the global South.15 Now, strategies that narrowly focus on the old state clubs of the global North rather than on pluralist multi-actor networks of multilateral cooperation are less likely to succeed.16 This creates significant uncertainty for governments, and also reduces state capacity and shrinks governments' policy space at precisely the time when challenges are mounting and becoming more complex.

There is a corresponding pluralization of principles and preferences about how to address problems collectively. As Keohane and Nye put it:

the problem posed by globalization is that the hierarchies—both the national governments and established international regimes—are becoming less ‘decomposable,’ more penetrable, less hierarchic. It is more difficult to divide a globalized world political economy into decomposable hierarchies on the basis of states and issue-areas as the units.17

Many different channels of cooperation have emerged, often in competition with existing institutions.18 Thus, ‘one-track’ strategies and unilateral or unilinear statecraft are likely to fail.

Historically, globalizations and socio-economic revolutions have generated new strategies for managing and exploiting interconnectivity. The same should be happening today, especially given the unprecedented speed and scale of twenty-first-century changes.

Effects on strategy and statecraft in the twenty-first century

If strategy is the art of creating power, how can it be mobilized in this contemporary context where power resources are dispersed and interspersed among interdependent actors? If statecraft is about securing state survival and prosperity, how can this be achieved when hyperconnectivity and power diffusion render many policy outcomes beyond the control of a single government?

As early as the mid-1970s, Ernst Haas made the point that the complexity of problems stemming from increased connectivity was rendering conventional strategic policy-making increasingly inadequate.19 Since then, the challenges to strategic policy-making have increased exponentially. The linkages between the human and natural spheres are denser and more complex, and this hyperconnectivity has generated new vulnerabilities.20 For example, Australia's Black Summer of 2019–20 and the wildfires on the North American west coast, in Siberia, and on the Amazon in 2020–21 have amply demonstrated the fragility and multiple stress points of socio-ecological systems, triggered by anthropogenic changes in the earth's climate system.21 Collective action problems have also been intensified by the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), characterized by radical technological developments that transcend divisions between the physical, digital and biological spheres. Such technological capabilities leave policy-makers constrained by a wider range of rivals, ‘including the transnational, provincial, local and even the individual. Micro-powers are now capable of constraining macro-powers such as national governments.’22

There are many ways in which we might theorize or investigate the effects of hyperconnectivity, power diffusion and 4IR on strategy and statecraft. Our first step is to highlight five basic problems that the condition we describe above poses for strategists and diplomats in general.

1 Shrinking policy space. The exponential speed at which these changes are happening, including their accumulated effects for countries, societies and industries, is transforming and diminishing the policy space for individual governments and actors. Even as globalization has pushed the connectivity and speed of interaction of socio-ecological systems to unprecedented levels, the capacity of governments to control outcomes and to deliver essential services has shrunk.

2 Connectivity and resilience. Connectivity is a double-edged sword—it can increase opportunities, wealth, even social resilience, but at the same time also increases sensitivity and vulnerability vis-à-vis our external environment.23 Because maximum connectivity results in maximum sensitivity and vulnerability, there is necessarily a trade-off between building resilience and increasing connectivity.24 As COVID-19 has amply illustrated, this is especially true when numerous interconnections—economics, finance, infrastructure, transport, ecology and health—multiply very quickly across a social system, generating unintended and unpredictable effects.

3 Policy nexuses. Many problems turn out to be interconnected in various ways with other issues and problems. When these interconnections are tight, non-uniform and non-linear in their nature, we get a nexus—for example, the nexus between pandemics and climate change; or the nexus between security threats and economic gains—which makes it harder to work out where and how to try to intervene to effect change.

4 Shifting boundaries and policy frames. The boundaries that divide individual, local, national, regional and international action have grown ever more blurred. Diverse sets of actors can group together to govern policy issues within specialized subsystems. As a result, new public policy spaces emerge beyond sovereign state authority, for example in the networks of national and international regulators, experts and the private sector that govern international financial activity.25

5 Raison de système. The global transformations of power and technology have led to a crisis of the state, which put governments under pressure to reinvent state capacity.26 Statecraft that narrowly focuses on ‘the national interest’ (raison d'état) alone, without taking into account the system context and potential system effects of individual policies, is inadequate for securing the survival and prosperity of a sovereign state. For this, governments need to develop the capacity to navigate hyperconnected socio-ecological systems (raison de système).27

Our reaction to recognizing these five core problems ought to be to develop better tools to deal with them. To be successful, strategists and policy-makers must be innovative and adaptive, and need to grasp details as well as adopt a more holistic view of the system context within which apparently discrete issues are embedded. Yet one common human reaction to such complexity is to seek refuge in oversimplification, tactics and process. The existing literature includes significant efforts to help us break out of such restrictive habits. The most important interventions, such as Lawrence Freedman's 2013 tour d'horizon, have focused on broadening out the notion of strategy, suggesting which of the growing actors, factors and vectors strategists need to take into account.28 In parallel, the social science academic and policy communities are now in broad agreement that contemporary global governance and multilateralism are operating on a ‘formal–informal continuum’,29 and have become ‘messy’, ‘ad-hoc’ and more ‘complex’.30

Other works suggest new concepts or approaches suitable for grappling with the problems of our age. Among the most influential is the sociologist Ulrich Beck's theorization of a ‘risk society’ geared to dealing systematically with the hazards and insecurities created by modern industrialization, and his hope for a reflexive ‘cosmopolitan micropolitics’ in which a greater variety of social actors contribute to dealing with these challenges.31 The fields of international politics and strategic studies have seen a corresponding growth in approaches stressing the management of risk and uncertainty, including efforts to engage with the problem of how foreign policy analysts may assess the ‘unknown unknowns’ in a more structured way;32 to understand why and how some states respond to geopolitical uncertainty using risk management strategies;33 and to emphasize the importance of strategic scripts and narratives and ‘repertoires’ of statecraft.34

By comparison, our aim is to develop a versatile framework suitable for dealing with the key problems of our hyperconnected and power-diffused world—a framework that has both conceptual significance and policy utility. The strategic diplomacy framework we outline below draws, in an approachable way, on key applications of the most suitable platforms of system theory and complexity science, without requiring readers and users to be specialists in these fields. Our aim is to harness key insights from complex systems thinking both to diagnose problems and to provide alternative strategies for improving policy outcomes in international affairs.35 We recognize that the key challenge is one of mindset, even as we introduce a set of diagnostic and policy tools that can be scaled and employed to deal with different policy issues. In this way, we try to bridge the gap between the academic quest for fundamental understanding and the urgent imperative of policy application.

The strategic diplomacy framework

In this section, we advance the concept of SD and introduce its accompanying innovative diagnostic and policy framework, which is geared towards an operational environment characterized by shrinking policy space, hyperconnectivity, policy nexuses and shifting boundaries. These problems create an urgent imperative for governments and other international actors to practise diplomacy and statecraft with a very clear emphasis on long-term and big-picture purposes and priorities—strategy, in other words. But strategizing is difficult in a complex world. Thus, our approach both stresses the necessity for a paradigm shift towards an explicitly holistic mindset when making strategy, and develops tools for navigating the wider system when practising statecraft.

We start from the important insight that contemporary international order is best understood as a complex adaptive system,36 with three key properties: interconnectedness,37 non-linearity38 and emergence.39 Such systems, like those found in cities or the human body, are dynamic, involve numerous moving parts, are hard to predict, and have the capacity for sudden and dramatic change.40 Analysts and practitioners accustomed to thinking in terms of linear causality (doing X leads to Y) and working within specialized areas face serious challenges, because:

- in addition to the direct effects of any action, the interconnections within a system can also produce indirect and delayed effects;

- the relationship between any two actors in the system is determined not just by how they act towards each other, but also by the interactions among the other members of the system; and

- one actor's actions may not lead directly to an intended result, because the outcome also depends on how the other elements in the system respond.41

To craft appropriate strategy and orchestrate effective statecraft under such circumstances, we need a paradigm that grasps the broader structures and systems within which specific policy issues are embedded. This requires what the Nobel laureate and physicist Murray Gell-Mann called ‘a crude look at the whole’.42 As the environmental scientist Donella Meadows rightly observed, while it might be

endlessly engrossing to take in the world as a series of events … that way of seeing the world has almost no predictive or explanatory value. Like the tip of an iceberg rising above the water, events are the most visible aspect of a larger complex—but not always the most important.43

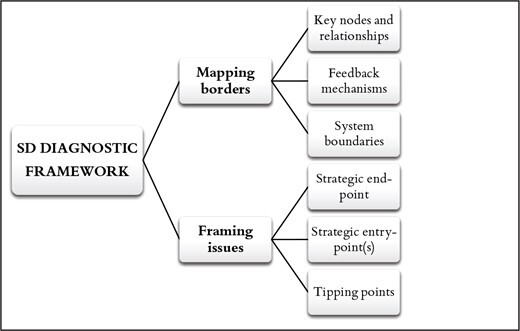

To capture this ‘big picture’ mindset necessary for strategy and statecraft, our concept of SD contains four elements, as set out in figure 1.44

Taking these elements together, we define SD as ‘the process by which state and non-state actors socially construct and frame their view of the world; set their agendas; and communicate, contest and negotiate diverging core interests and goals’.45 This conceptualization integrates statecraft as a constant element within the broader enterprise of strategizing. It emphasizes that operating within conditions of uncertainty requires sustained effort at making sense of the larger complex within which problems are embedded, and developing effective practices of negotiation, contestation and representation. As highlighted in our policy tools below, it also requires reflexive practices of re-evaluation to improve policy and strategy.

Our next step addresses the question: now that we know it's complex, what are we supposed to do about it? We operationalize the SD concept for practice by developing SD as both a diagnostic tool and a policy tool.46 Together, these provide a conceptual framework within which to understand the broader system context for policy issues; and a practice framework to help develop effective system-oriented strategies for statecraft in the short and long term.

The SD diagnostic framework

The diagnostic framework is an SD toolkit that enhances our repertoire of ways of representing and framing problems.47 It grapples with complexity by examining the wider domestic, regional and global systemic environment within which a specific policy issue is embedded (see figure 2). As Meadows reminds us:

We have to invent boundaries for clarity and sanity; and boundaries can produce problems when we forget that we've artificially created them … Where to draw a boundary around a system depends on the purpose of the discussion—the questions we want to ask.48

Thus, issue boundaries are ultimately the choice of the strategist.49 While statecraft has traditionally focused on how governments organize their relationships with the outside world in the pursuit of the national interest, the SD framework is interested in the systemic contexts and implications of those relationships. Our analytical focus is on navigating the system, with two diagnostic objectives: mapping borders and framing issues.

Mapping borders involves identifying the key nodes/actors, flows and relationships, including feedback loops, driving the long-term dynamics of the system within which a policy issue is embedded. In identifying key drivers, the strategist follows the principle of diminishing relevance that can be observed over time, distinguishing between immediate, intermediate and distant variables. Relevance is derived from both long-term system analysis and strategic purpose and intent. Since system boundaries are not fixed, the strategist has considerable latitude when drawing the boundaries around a policy issue. Policy innovation starts with this diagnostic act of bounding the problem.

In framing issues, SD's analytical approach explicitly acknowledges the nexuses specific policy issues can form with interconnected problems. Issue framing comprises three essential tasks:

1 Identifying the strategic end-point: what is the final objective of the proposed policy or action taken to intervene in the system?

2 Identifying the most appropriate strategic entry-point(s): given that we cannot assume linear or singular causality in complex systems, what are some of the most promising actors, channels or institutions to act upon or try to influence, so as to leverage potential system effects? This might involve creating alterations in underlying system goals, mindsets or norms, or changing parts of social structures that can trigger a larger change in system behaviour.50

3 Identifying potential tipping points towards which the proposed intervention may push the system. What kind of feedback loops might the proposed policy trigger—negative feedback, in which the system as a whole adjusts to preserve the existing equilibrium, or positive feedback, which pushes the system over into a new equilibrium?51

These requirements of the SD diagnostic framework help us to be explicit about our problem representation, strategic purpose and tactical pathways. The process helps to expose and to enable assessment of the mental models underlying policy-making, because strategies tend to be derived from largely internalized and implicit mental maps that give political situations a particular meaning.52 By design, mapping borders and framing issues are foundational steps that need to be continuously reassessed in the practice of strategy and statecraft.

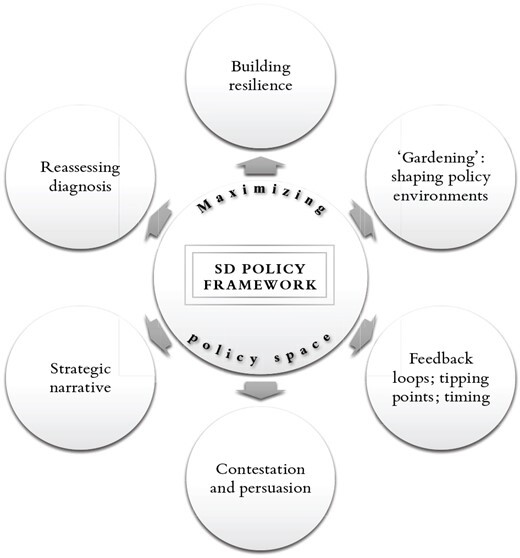

The SD policy framework

Having diagnosed the policy problem, we move to crafting policy interventions in a complex system. Here, the central challenge is to alter the dynamics of the system so as to maximize the possibility of results favourable to our strategic ends, while avoiding unexpected and undesired outcomes. The objective is to (re)gain and maximize policy space, and this requires a balance between indirect policy facilitation and direct policy action to achieve desired outcomes (see figure 3). It also transcends the domestic and international levels of analysis and policy arenas.

The SD policy framework is a set of six guidelines, indicating key considerations necessary for those trying to maximize policy space in complex systems:

1 Building resilience. Resilience is the sine qua non for harnessing connectivity and navigating complex systems.53 For example, governments need to build a resilient infrastructure that keeps intact vital hubs of the domestic and global ecosystems—economy, finance, transport, cyber, energy, water, food. Diversification of strategies and global supply chains is of fundamental importance for the ability of complex systems to bounce back quickly after large perturbations.

2 ‘Gardening’—shaping policy environments. Statecraft under complexity can be neither coercive nor laissez-faire.54 The challenge is to strike a balance between indirect facilitation (the ‘gardening’ approach) and direct action in particular issue areas. In complex adaptive systems, policy outcomes do not emerge as the direct result of linear cause–effect activities, because X does not necessarily cause Y. The ‘gardening’ approach favours shaping strategic environments so that they become conducive to the achievement of desired policy outcomes. Policy interventions in complex systems require ‘not a heavy hand, not an invisible hand, but a nudging hand’.55

3 Managing feedback loops, tipping points, timing. Amplifying and dampening feedback loops are essential features of complex adaptive systems. Amplification may lead to tipping points which cause major change in the state of the system. Strategies that favour the status quo depend on the capacity to nudge, nurture or delay—if not prevent—tipping points.56 The strength and timing of interventions are as important as the appropriate entry-point. Because complex systems can self-adjust and self-organize, inappropriate intervention may cause the system either to overreact or to generate unintended consequences.57

4 Contestation and persuasion. In the absence of a compelling global strategic frame such as empire, unipolarity or the Cold War, strategies themselves become the sites of contest and conflict at both the national and international levels. SD as a policy framework therefore includes the diplomatic practices of presenting, contesting and negotiating strategic ideas to generate buy-in from strategic audiences.

5 Strategic narrative. Ancillary to the previous point, SD cannot function effectively without a story plot that is told with consistency and clarity. The strategic narrative represents and interprets a policy issue in a simple and compelling way to facilitate support from key stakeholders and strategic audiences.

6 Reassessing diagnosis. Underlying SD must be a learning infrastructure that regularly reassesses the initial diagnosis of a policy problem when using the SD policy framework. By design, strategy and statecraft are subject to adaptation, adjustment and recalibration. Complex systems can only be governed by embracing errors and policy failures. Learning after trial and error is therefore a feedback loop in itself and the primary source of policy innovation.

Together, the SD diagnostic and policy frameworks help to make explicit our cognitive biases and limitations, and to combat their negative effects by providing a toolkit of steps or questions that we should be asking when dealing with strategic problems within complex systems.

Putting strategic diplomacy to work

This section demonstrates how the SD approach can be used to navigate major international challenges within their respective systemic operational environments, and adds value beyond current analyses. We provide three case-studies across issue areas of different scopes and domains to show how SD generates critical leverage by recasting conventional analyses of well-known and debated contemporary strategic problems—power competition in Asia; intervention and peacebuilding; and pandemics and COVID-19. While space constraints prevent us from conducting full SD diagnostic and policy exercises, these examples are complementary and together highlight the comparative advantages of the SD framework.

Rethinking power competition in Asia

In addressing the manifold challenges of the ongoing transitions of power and order caused by China's resurgence and the decline of US hegemony, many analysts tend to focus on the question of whether and when the United States and China are destined to go to war.58 But framing the challenges of global power diffusion and power transition in this way captures only a small slice of the attendant complex problems with which policy-makers must grapple. Employing the SD framework helps to address such cognitive biases. Regional security and strategic policy in Asia are not merely about lining up on either side of the Sino-American great power rivalry. Recognizing the wider systemic context within which this power competition is embedded highlights that there is uneven diffusion and disaggregation of power across different realms—in particular, the highly interdependent economic and financial arenas are less susceptible to the exercise of unilateral power and zero-sum games.59 At the same time, many other stakeholders in the crowded Asian security landscape—major regional and external powers, transnational corporations, etc.—are finding different ways to protect their sovereignty and economic interests, and to influence or manage the evolving regional order. Here, we explore competing ‘strategic imaginaries’ as an excellent example of how the SD framework can be used to diagnose and understand the bigger regional picture of power diffusion and competition, and to help develop appropriate policy responses.

In contemporary politics, Asia is redefined and reimagined on an ongoing basis. A regional construct is never value-neutral: ‘the implicitly or actively drawn borders associated with it, inclusion and exclusion mechanisms, and the attribution of particular characteristics are always political in nature’.60 These dynamics are related—but not reducible—to great power competition. Thus, for example, President Xi Jinping's 2014 call for an ‘Asia for Asians’ reflected the longstanding post-Cold War struggle between ‘exclusive’ forms of east Asian regionalism and more ‘inclusive’ versions such as the various ‘Asia–Pacific’ forums and initiatives. The most recent iteration of these competing visions is the ‘Indo-Pacific’, a meta-region that would connect the two vast oceans and everything in between into a giant maritime strategic theatre. The idea originated in close association with efforts at forging ‘quadrilateral’ security cooperation (the Quad) among key US allies and partners, and took off in parallel with what came to be called China's ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI).61 Thus, ‘Indo-Pacific’ rhetoric and activities are commonly refracted through the lens of zero-sum competition with China and the BRI, a rival ‘strategic system’ in the contest for geostrategic control and geo-economic influence.62

As countries in the region and beyond work out their responses to this latest round of reimagining Asia, the SD diagnostic framework helps shed light on two fundamental issues:

Mapping borders The contest to define the region involves an argument about how to map the boundaries of the system around Asia that strategists who want to exert power and influence there should use in planning their operations. Thus, great power rivalry entails a broader set of competing ‘strategic imaginaries’. Combining our appreciation of complex systems with the traditional notion of geopolitics, we may think of a strategic imaginary as stipulating a prioritized set of connections: which connections between which parts of the system are more important than others? Thus, geopolitical competition is essentially a contest over which imagined connected community is most important—not necessarily a zero-sum fight to eliminate alternative imaginaries. In Asia today, the ‘Indo-Pacific’ is only one of three competing strategic imaginaries; the other two are the ‘Asia–Pacific’—which is already fleshed out with significant political, economic and strategic resources and institutions—and the still nebulous vision of a Eurasian continent and a Pacific–Indian oceanic arc circumscribed by a risen China associated with the BRI. All three imagined meta-regions require very significant projections of resources and political will to substantiate and to sustain as lived realities.63 Many of their boundaries and key nodes overlap, and each has a variable set of purposes. Thus, we should expect that these three strategic imaginaries will continue to mark the regional landscape for the foreseeable future, providing multiple avenues and arenas for competition, but also for strategic choice.

Framing issues From an SD perspective, navigating such overlapping systems involves an initial diagnosis of how issues are framed within these competing imaginaries. To illustrate, we can contrast the Indo-Pacific and the BRI. The former seemed, especially in 2016–18, to be an enterprise undertaken by the Quad with the aim of containing China. Reinforcing US primacy in this expanded strategic arc was both the key means and the accompanying end-point.64 The chosen entry-points were the existing bilateral alliances between the United States and its key regional allies, Japan and Australia, and the new security partnership with India as the new key node in the US-hegemonic system. Rhetorically, democracy and ‘the rule of law’ underpinned the strategic narrative of a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP).65 By comparison, the BRI is generally regarded as a means to the end of ensuring continued Chinese economic growth through the export of excess capital, or of expanding China's sphere of influence by using economic tools to build connectivity with multiple regions.66 Either way, the end-point is expanding the bases for China's power and influence. The entry-points are rather different, focusing on economic tools such as infrastructure investment and ideas like ‘security through development’, and on poor and developing countries and constituencies.67

Importantly, this diagnosis opens a wider range of options for states considering their engagements with these agendas than might otherwise appear if they adopted a purely great power rivalry lens. For example, while the end-points of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ and BRI imaginaries seem to be diametrically opposed, the differences in their entry-points could create room for manoeuvre by regional actors wanting to navigate both systems.

If the prevalent US–China rivalry lens were sufficient, we should expect to see regional states adopting strategies and policies that picked one side and were geared towards the containment of the other. We should see countries choosing to operate exclusively within either the BRI system or the Indo-Pacific system, and probably de-emphasizing the older and looser Asia–Pacific system. However, there is evidence of regional states adopting a wider variety of strategic responses than this. In particular, two important east Asian actors—Japan and the south-east Asian countries—appear to be employing the type of broader and more indirect systems tools emphasized in our SD policy framework.68

Since 2018, disagreements about the end-points of the Indo-Pacific imaginary have become evident in discursive and policy adjustments by key regional partners. As US rhetoric increasingly presented the FOIP as a values-laden enterprise antagonistic towards China, Japan especially began to pull back. While Tokyo clearly supports the end-point of maintaining US hegemony and a ‘rules-based order’ in the region, it also wants to avoid the tipping point of antagonizing China so much that the regional system spirals towards outright war. For Japanese leaders, system resilience remains tied to the avoidance of war and the attendant collapse of economic order. Japanese contestation of the Indo-Pacific imaginary from within first involved narrative modification. Between 2018 and 2019, official Japanese policy discourse on the FOIP switched from calling it a ‘strategy’ to the less antagonistic ‘vision’; de-emphasized maritime security; and avoided references to the Quad, human rights, democracy or ‘fundamental values’.69 Materially, Tokyo has also led the four FOIP partners to compete with China in a different arena, by creating the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI) initiative, offering alternatives to Chinese funding for projects in the region. The Abe administration also made a public commitment to cooperate with China's BRI, signalling to other countries that they would not have to make a zero-sum choice between BRI and PQI funding.70 In essence, Japan has been reshaping the Indo-Pacific imaginary by recasting it away from exclusionary, zero-sum policies focused on security containment.

The other potential tipping point that seems to concern Japan is the loss of support from south-east Asian states—a constant Japanese worry that makes little sense from a purely military point of view, but is more understandable from the perspective of trying to maintain a diversity of political and economic partners to ensure overall system resilience. The Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) has also employed indirect and non-zero-sum tools to reshape the Indo-Pacific imaginary. This imaginary was symbolically adopted in the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP), but then quickly diluted by recasting its values in terms of the familiar ASEAN norms of ‘openness, transparency, inclusivity’ and ‘a rules-based framework’. Subsequently, ASEAN rarely employed the AOIP concept. As Tan argues, this move reclaimed the geopolitical narrative, mainly to neutralize it.71 Many in ASEAN regard the ‘Indo-Pacific’ as superfluous: the association had, after all, spent three decades after the end of the Cold War fleshing out the existing ‘Asia–Pacific’ imaginary in economic, security and institutional ways that already included the Indian subcontinent and Indian Ocean.

The SD policy framework can be equally helpful for those who wish to double down on more exclusionary, zero-sum security end-points in Asia's power competition. An emphasis on the wider systems context of competing strategic imaginaries suggests several key areas of focus. First, to bolster the resilience of a putative system that contains China, it will be important to consider how to promote deeper and wider support. One crucial factor is whether to offer a non-binary choice: how can partners be persuaded to commit to the FOIP even as they participate in the BRI and continue to benefit from existing Asia–Pacific institutions and connections? Second, proponents of a ‘hard’ FOIP must pay more attention to shaping key partners' preferences, especially by improving ways to deal with contradictions such as the economic blowbacks of antagonizing China. They will have to help overcome allies' and partners' economic and political dependencies on China and to find ways to sustain their support for more hard-line values centred on democracy, human rights and the rule of law. Finally, a ‘hard’ FOIP will feed a positive feedback loop that may antagonize China towards the tipping point of conflict. Thus, proponents of this route will need to have a game plan for how to fight and win such a conflict.

Rethinking intervention and peacebuilding

On 14 April 2021—two decades after NATO invoked, for the first time, article 5 of the Washington Treaty to target Al-Qaeda's Afghan bases in retaliation for the 9/11 terrorist attacks—the United States and its allied partners announced the complete withdrawal of NATO forces from Afghanistan.72 On that same day, the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan issued a report warning of ‘the urgent need for measures to reduce violence and the ultimate, overarching need to reach a lasting peace agreement’.73 The long military and humanitarian engagement in Afghanistan, which had cost over US$2 trillion,74 came to an end abruptly, without peace or stability. That intervention serves as a strong reminder that societies emerging from conflict are complex social systems in which foreign interventions have only limited effect. Peace and stability cannot be imposed.75

In August 2021, just before the fall of Kabul and the chaotic withdrawal of international forces, the US Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) stated in his annual ‘lessons learned’ report that ‘no single agency had the necessary mindset, expertise, and resources to develop and manage the strategy to rebuild Afghanistan’.76 Strategic ends, ways and means were misaligned. Twenty years of engagement had resulted in a broad range of activities that, to paraphrase SIGAR, did the wrong thing perfectly well.77

Applying the SD diagnostic framework to conflict in Afghanistan helps to recast the challenges of intervention and peacebuilding by highlighting three critical needs.

1 Long-term and integrated strategic planning capabilities prior to and during deployment. While the US Department of State had been entrusted with overseeing reconstruction in Afghanistan, it had neither the analytical nor the strategic capacity to do so. The Department of Defense had the resources and strategic expertise for military operations, but it lacked the capabilities to run large reconstruction programmes with major economic and institution-building elements.78 There was no coherent and robust whole-of-government strategy.

2 Mitigating cognitive biases when analysing complex problems. This is the sine qua non for getting decisions right at the strategic, operational and tactical levels. Cookie-cutter approaches that seek to replicate policies from one conflict setting to another do not work, as each complex social system follows fairly unique dynamics. For example, US policy-makers' perception that the counter-insurgency strategy used in Iraq could be replicated in Afghanistan ignored fundamental differences in the two countries' social, cultural and political circumstances.79

3 Learning hard lessons. Historically, interventions in civil wars have shown the limited utility of modern western armies in counter-insurgencies.80 For the United States, this historical lesson had been readily available since the fall of Saigon in 1975. In Vietnam, in March 1965, the Lyndon B. Johnson administration believed itself to be undertaking a systemic battle to prevent Cold War dominoes from falling. Yet in fact the United States entered a civil war on the losing side. For Afghanistan, containing the insurgents rather than winning the counter-insurgency might have been a more attainable goal.

Mapping borders Using the SD diagnostic framework, we can reassess the system boundaries within which conflict in Afghanistan is embedded. Who are the key actors, and what are the key issues? Apart from the United States and its allied partners, key stakeholders include China, India, Iran, Pakistan and Russia. Those relationships need to be nudged and nurtured in any comprehensive approach to stabilize the country. For example, while the United States maintained an operational base in Pakistan for drone strikes and other activities against the Taliban at least until 2011, Pakistani support and sanctuary for the Taliban seriously undermined the US-led intervention in Afghanistan. China has had a strong interest in promoting regional stability to protect its economic interests in the BRI central Asia economic corridor. Institutionally, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, with its focus on counterterrorism, regional security and development, provides another key regional node, because it involves all the above stakeholders.81

The critical issue that has been a key driver of conflict and instability is Afghanistan's role as the world's largest producer of opium. Since the 1980s, the illicit drug economy has been firmly entrenched, providing critical livelihoods for many Afghan people.82 The illegal drug trade is woven into the country's socio-economic fabric, providing profits not only to the Taliban but also to the Afghan police, tribal elites and individuals at various levels of government. Without the poppy economy, large parts of the rural population face hardship, with negative consequences for access to food, medical treatment and schooling for children.83 In 2017, with more than half the population living below the poverty line, poppy cultivation provided 590,000 full-time jobs.84 Consequently, peace, security and stability in Afghanistan are directly dependent on the creation of alternative livelihoods and a broader economic development strategy.

Thus, intervention in Afghanistan is a policy challenge with regional and global dimensions that need to be addressed simultaneously. Any strategy for stabilizing Afghanistan must go beyond the domestic realm and navigate the systemic context within which the conflict is embedded.

Framing issues In rethinking the Afghanistan intervention, and following on from the above, three observations stand out:

1 Strategic ends, ways and means must be fully aligned. Clarity about the strategic end-points of a mission is essential to avoid both strategy- and mission-creep. While the US-led intervention initially focused on the defeat of Al-Qaeda, it subsequently expanded to include the defeat of the Taliban, and then further extended its focus on anti-corruption, counter-narcotics and nation-building. According to SIGAR, ‘the US government was simply not equipped to undertake something this ambitious in such an uncompromising environment, no matter the budget’.85

2 If military counterterrorism was the primary strategic end-point of the mission, then any other goals (such as counter-insurgency, counter-narcotics, socio-economic development, and promoting democracy, rule of law, women's rights and human rights) would necessarily be subordinated to that end. But if there is a broader understanding of counterterrorism beyond the military dimension, then those secondary and tertiary goals may serve as entry-points to help achieve the primary strategic end-point. However, if entry-points are turned into or conflated with strategic end-points, then a fundamental redesign of the mission is required.

3 Prioritization of strategic goals and commensurate resource allocation is key. Pursuing the primary strategic objective of counterterrorism will render unobtainable some of the secondary and tertiary goals. For example, a counter-narcotics policy based on the eradication of poppy is not an option if local support is needed to obtain intelligence on the Taliban and Al-Qaeda.86

After the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan, there is an opportunity to rethink and redesign a strategy of engagement that is led by the UN and supported by regional stakeholders, with sustaining peace and stability as the strategic end-point.87 In this scenario, the UN and its agencies would facilitate conditions conducive to sustainable peace rather than pursuing the implementation of liberal ideas of democracy and justice that featured strongly in previous nation-building attempts. Intervention and peacebuilding are about working with complex social systems rather than against them.

How does the above diagnosis inform the SD policy framework for sustaining peace and stability in Afghanistan?

1 Shaping policy environments (raison de système). The primary policy focus must be on how the society emerging from conflict can self-organize, with national ownership that includes representatives from all strata of society. The post-Cold War peacebuilding paradigm by and large followed a linear cause–effect logic with an almost guaranteed successful outcome if the deterministic design of a liberal peace end-state was applied.88 The SD policy framework envisages external parties performing the function of ‘gardeners’, shaping a policy environment that is conducive to the achievement of national reconciliation and a robust degree of social cohesion.

2 Building resilient social institutions. External parties can facilitate the building of a domestic resilience infrastructure to better withstand pressures to relapse into violent conflict.89 For this, systemically relevant policy initiatives may include security sector reform, investment in social justice, and boosting the economic foundations of societies by creating legal revenue streams and services.90 However, all that needs to be embedded in the domestic social and cultural context; for example, in Afghanistan one cannot impose formal institutions on a society that runs on informal rules.91

3 Tipping points. It is essential to be clear about which tipping points should be avoided—e.g. relapse into civil war; re-emergence of terrorist sanctuaries—and what tipping points ought to be nudged and nurtured—e.g. the collapse of the illicit drug trade; public acceptance of the Afghan government's legitimacy. Most of these objectives are shared by the key regional stakeholders.92

4 Strategic narrative. There also seems to be little objection to the aspiration of turning Afghanistan into an indispensable regional economic, transport and energy thoroughfare, as this would lock the country on a sustainable development path with tangible benefits to its neighbours.

5 Reassessing diagnosis after trial and error. Sustaining peace is not a one-off policy innovation exercise but naturally involves a long-term commitment of external parties to trial and error and learning. Constant reassessment of the problem diagnosis is of key importance for adjusting and fine-tuning peacebuilding policies.

In sum, peacebuilders need to address the central question of how complex social systems can be nudged, and how feedback loops at the regional and global levels can be dampened or amplified in support of the domestic political and social capacities to sustain peace. In terms of policy execution, this approach comes close to de Coning's idea of ‘adaptive peacebuilding’.93 The added value of the SD framework is to offer diagnostic leverage in framing policy issues within their systemic context prior to policy execution, and to identify critical strategic entry- and tipping points that are relevant for intervention and peacebuilding.

Rethinking pandemics and COVID-19

The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic which emerged in central China in late 2019 and at the time of writing continues to rage across the world highlights the Janus face of twenty-first-century globalization, underpinned by open international borders and deregulated global trade and finance. While globalization has substantially increased the wealth of nations and has facilitated unprecedented mobility and convergence across societies, it has also substantially increased vulnerability and sensitivity to systemic disruption, precisely because of hyperconnectivity. The contemporary integration of global relationships and systems in economics, finance, infrastructure, transport, ecology and health sets the twenty-first century apart from previous eras. Thus, pandemics can create global system shocks. When the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020, most national governments were underprepared, despite epidemiologists having warned for decades that epidemics will become more frequent because of the interconnected problems of globalization, population growth, inequalities and climate change.94

Applying the SD diagnostic framework, we first examine COVID-19 in its wider systemic context.

Mapping borders COVID-19 is a global systemic crisis. Pandemics, while primarily addressed within the political boundaries and jurisdiction of sovereign states, are in fact embedded in a global system and need to be fought as such. National responses to global pandemics can only be partial and are ineffective in the long term: COVID-19, like any other global pandemic, requires systemic responses, including scientific collaboration and joint global leadership. Most importantly, COVID-19 needs to be diagnosed in its broader socio-ecological context. Connectivity is the key variable that renders the eco- and social systems inseparable and drives socio-ecological feedback loops. The implications are profound. Outbreaks of zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19, including the emergence of variants or mutations, will become increasingly likely because of anthropogenic climate change. While vaccinations limit adverse health impacts and reduce transmissions, they do not eradicate the virus. Future mutations of the virus that are less susceptible to antibody neutralization may require the development of new vaccines. As COVID-19 becomes endemic, this global systemic crisis requires a fundamental rethink of what is sustainable and what is responsible in twenty-first-century globalization.

Framing issues If the unmitigated global spread of deadly viruses is the tipping point to be avoided, sustainable globalization must be the strategic end-point. This end-point directly targets the goals and paradigms of our deeply interconnected socio-ecological system. Without adjusting goals and paradigms, the system may lose its capability to self-organize and may collapse. To pursue the end-point of sustainability, COVID-19 needs to be framed as a systemic crisis beyond a public health issue fought primarily at the national levels of 194 WHO member states. Eradicating the virus and achieving herd immunity—the condition in which someone infected, on statistical average, will not infect another person—are not suitable strategic entry-points, for two reasons.95 First, we are dealing with a truly global herd that is guarded by more than 194 shepherds. There is no synchronized effort to protect this herd through a global and simultaneous vaccine roll-out.96 Second, COVID-19 is not like the measles, which can be eradicated with global vaccinations. Considering the existing multiple variants of the virus and potential future mutations, this is a pandemic that can only be contained.

Connectivity and resilience constitute the most promising strategic entry-points to achieve sustainability. This is an opportunity to reset globalization by renegotiating the acceptable trade-off between connectivity and resilience in such a way as to recalibrate societal ways of life towards environmental and social responsibility and sustainability.97 Hyperconnectivity has significantly reduced the resilience of societies, and unconditional commitments to openness can be revoked. Governments everywhere have responded to COVID-19 by limiting connectivity through lockdowns, travel restrictions and border closures. In a systemic crisis, connectivity is a policy lever that needs to be recalibrated with the aim of recovering resilience to promote the health of societies.98 While countries cannot afford to close their borders perpetually, the key question is how to optimize the opportunities of system connectivity while minimizing its risks.

In short, COVID-19 ought to be framed within its much broader planetary systemic context, with the sustainability of globalization as the strategic end-point. Avoiding the tipping point of unmitigated global spread of viruses, the most appropriate strategic entry-point is to mitigate systemic vulnerability and sensitivity through a careful recalibration of connectivity and resilience.

Applying the SD policy framework, several implications follow. Strategy and statecraft are required to position, prepare and nudge national systems into what we call the ‘zone of resilience’ (see figure 4).

Mitigating vulnerability and sensitivity through zones of resilience

Mitigating vulnerability and sensitivity through zones of resilience

1 Building national zones of resilience. The principle of diversification—of food, medical, other strategic supplies—is essential to building some redundancy into the system so that there are multiple points of potential failure rather than a single vulnerable supply chain. A related point is the need for better shock-proofing of critical infrastructure. As we have seen from a relatively successful case like Singapore, a broader-based capacity to respond to a pandemic must include the entire health system, from general practitioners to general hospitals and specialist communicable disease facilities. But there are also weak links in other critical infrastructure: for instance, Australia fortunately produces a great deal of its own food—but food security in times of global supply chain disruptions entails having more credible national stockpiles of fuel necessary to transport this food and produce across a continent.99

2 Shaping policy environments through gardening. Strategy and statecraft for COVID-19 requires a sea-change in policy-making mindsets, from the traditional focus on the national interest (raison d'état) to a new emphasis on shaping policy environments to keep our hyperconnected socio-ecological systems thriving (raison de système). A pandemic must be fought equally hard on the economic front by a mix of direct and indirect policy measures. Across the globe, especially in developing regions— most notably in Africa, south Asia and south-east Asia—the economic repercussions of COVID-19 have been greater than those of the global financial crisis.100 Nudging both national and global economic recovery is critical. For example, the US $1.9 trillion stimulus package, adopted in March 2021, will have system effects, adding about 1 percentage point to global economic growth in 2021.101 However, for system-wide international economic recovery, it will be necessary to reduce the financial pressure on vulnerable low-income countries. Building on the G20's ‘Action Plan Supporting the Global Economy through the COVID-19 Pandemic,102 and refraining from trade protectionism and competitive currency devaluations will be essential to boost the resilience of the multilateral trading system.

3 Harnessing feedback loops. Strategy and statecraft need to harness the stabilizing or amplifying feedback loops that drive complex adaptive systems. Governments can identify more effective ways to mobilize and amplify state capacity to fight diseases of connectivity like COVID-19. For example, richer countries or international health organizations should establish an international pandemic monitoring system to track incidence and data in each world region. Such an early warning system could be the first line of defence, even before the disease reaches a particular country's shores. Once a pandemic breaks out, it needs to be fought not only at the current epicentres, but also at the weakest links in the international system—refugee camps, slums, fragile states with weak state capacity and countries with very poor health systems. Those with more resources must intervene to assist early in these areas, because a collapse at these points can trigger cascades and tip the system into a new unpredictable situation. At the time of writing, only 2.5 per cent of people in low-income countries have received at least one vaccination dose, which leaves too many people susceptible to infection.103 To minimize the possibility of severe disease and boost systemic resilience, vaccines need to be rolled out globally and simultaneously to as many people as possible. One policy implication is that, if double-shot vaccinations already prevent serious illness and hospitalization, then where possible global first-dose vaccinations must take priority over national booster doses for the time being.

4 Strategic narrative. Public education and mobilization capacity are imperative for managing COVID-19 and the globalization reset. There is no silver bullet here; governments must develop a strategic narrative to navigate their own countries’ particular political systems and social attributes by trial and error to find the most appropriate means of ensuring a high degree of public confidence and compliance.

5 Reassessing diagnosis. Built into the SD framework for COVID-19 is an ongoing review that constantly reassesses the diagnosis underlying the policy framework. For example, if scientific evidence emerges that there is an increase in hospitalization among those who have been vaccinated, then policy adjustment must follow, and booster shots would need to be prioritized in response.

In sum, COVID-19 lays bare the crucial variable of state capacity, of which one vital element is the ability to make strategy and exercise statecraft. Changing strategic mindsets at the national level is key to mastering this fundamental challenge of our time.

Conclusion: strategic policy for the twenty-first century

The twenty-first century, a century of complexity, carries enormous disruptive potential for international security, national economies and societies. In an environment of hyperconnectivity, power diffusion and 4IR, governments around the world must cope with the twin effects of shrinking policy space and the interconnectedness of policy issues. Effective strategy is essential for minimizing uncertainty, mobilizing power and maximizing policy space.

In this article, we have introduced our concept of strategic diplomacy and its attendant diagnostic and policy framework for strategizing complexity and maximizing policy space. Using key insights from complex systems thinking, the framework advances a set of principles and guidelines for mapping and managing strategic problems by reshaping policy ecosystems to achieve the outcomes policy-makers want, rather than addressing a specific policy problem in isolation. Government policy-makers and university academics have different priorities when addressing policy problems. Government is mainly concerned with improving structures and processes for policy-making, so that their policies and instruments are more sustainable and better informed by solid frameworks that consider cross-cutting issues. Academics may be more interested in building comparative empirical knowledge about how policy-makers adapt to changing international systems over time and in theorizing such adaptations. Strategic diplomacy is explicitly pitched at the middle ground between these two approaches. Fundamentally, it aims at developing a mindset and framework to facilitate integrated policy and decision-making at the intersections of different issue areas and governance challenges.

We have argued that harnessing complexity requires a sea-change in strategic imagination and policy mindsets. The SD framework makes explicit the mental models underlying the mapping and framing of policy issues. It may well be that complex systems-informed analysis is but one way of dealing with the hyperconnected, non-linear and unpredictable systems-affecting problems confronting us all today. Given the grave nature of these challenges, we look forward to seeing other appropriate approaches being suggested. Clearly, strategies derived from unarticulated, internalized mental maps are insufficient. Instead, twenty-first-century strategic policy must encourage out-of-the-box thinking and embrace constant and conscious reassessment of the fundamentals upon which policy planning and policy-making are pursued. As James Joyce's Stephen in Ulysses taught us a hundred years ago, there is an element of genius in making volitional errors. Hence navigating the ship of state between the Scylla of globalization connectivity and the Charybdis of national resilience will ultimately lead to the portals of discovery and subsequent learning.

Footnotes

Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: a history (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. xii.

Morton A. Kaplan, ‘An introduction to the strategy of statecraft’, World Politics 4: 4, 1952, p. 548.

See Moisés Naím, The end of power. From boardrooms to battlefields and churches to states: why being in charge isn't what it used to be (New York: Basic Books, 2013).

Evelyn Goh, The Asia–Pacific's ‘age of uncertainty’: great power competition, globalisation, and the economic–security nexus, RSIS working paper no. 330 (Singapore: S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 2020), p. 2.

Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, ‘Introduction’, in Joseph Nye and John D. Donahue, eds, Governance in a globalizing world (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2000), p. 2; Markus Kornprobst and T. V. Paul, ‘Globalization, deglobalization and the liberal world order’, International Affairs 97: 5, 2021, pp. 1305–16.

Robert Jervis, System effects: complexity in political and social life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997); Robert Axelrod and Michael D. Cohen, Harnessing complexity: organizational implications of a scientific frontier (New York: Basic Books, 2000).

William H. McNeill, Plagues and peoples, 2nd edn (New York: Anchor, 1998).

See Donald A. Henderson, ‘The eradication of smallpox—an overview of the past, present, and future’, Vaccine, vol. 29, supplement 4, 2011, pp. D7–9.

Evelyn Goh and Jochen Prantl, ‘Strategic policy for COVID-19: connectivity with resilience’, Strategic Diplomacy Policy Memo no. 1, 5 April 2020, https://6f9c2a16-6c8b-4753-b77f-6f714dc3398e.filesusr.com/ugd/712891_567227e1e97944c3a14d3f021edbca43.pdf.

For a less benign picture of the Roman empire, see Adrian Goldsworthy, Pax Romana: war, peace and conquest in the Roman world (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016).

The Pax Sinica can be traced back to the Han (206 Bce–221 Ce), Tang (618–907), Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties of the Chinese empire.

Pasai in northern Sumatra, Melaka in south-western Malaysia and the Siamese Kingdom of Ayutthaya are examples. See David C. Kang, East Asia before the West: five centuries of trade and tribute (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), pp. 204–208; Peter Lee and Alan Chong, ‘Mixing up things and people in Asia's port cities’, in Peter Lee, Leonard Y. Andaya, Barbara Watson Andaya, Gael Newton and Alan Chong, eds, Port cities: multicultural emporiums of Asia, 1500–1900 (Singapore: Asian Civilization Museum, 2016), pp. 30–41.

Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II, 2 vols (New York: Harper & Row, 1972).

Norrin M. Ripsman, ‘Globalization, deglobalization and great power politics’, International Affairs 97: 5, 2021, pp. 1317–33.

Andrew Hurrell, ‘Effective multilateralism and global order’, in Jochen Prantl, ed., Effective multilateralism: through the looking glass of east Asia (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), pp. 21–42.

Jorge Heine, ‘From club to network diplomacy’, in Andrew F. Cooper, Jorge Heine and Ramesh Thakur, eds, The Oxford handbook of modern diplomacy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 54–69.

Keohane and Nye, ‘Introduction’, p. 30.

Jochen Prantl, ‘Taming hegemony: informal institutions and the challenge to western liberal order’, Chinese Journal of International Politics 7: 4, 2014, pp. 449–82; Andrew Hurrell, ‘Beyond the BRICS: power, pluralism, and the future of global order’, Ethics and International Affairs 32: 1, 2018, pp. 89–101.

Ernst B. Haas, ‘Is there a hole in the whole? Knowledge, technology, interdependence, and the construction of international regimes’, International Organization 29: 3, 1975, pp. 827–76.

Oran Young, Governing complex systems: social capital for the Anthropocene (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017).

Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, Report (Canberra, 28 Oct. 2020), https://naturaldisaster.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/royal-commission-national-natural-disaster-arrangements-report. (Unless otherwise noted at point of citation, all URLs cited in this article were accessible on 31 Oct. 2021.)

Klaus Schwab, Shaping the future of the fourth industrial revolution: a guide to building a better world (London: Penguin, 2016), p. 67.

Sensitivity is defined as the mutual effects arising from system connectivity. Vulnerability denotes the opportunity costs of disrupting system connectivity.

Hence connectivity boosts an actor's resilience—understood as the capability to bounce back from systemic shock—only up to a point, after which the relationship can become inverse. See Thomas Homer-Dixon, ‘Complexity science’, Oxford Leadership Journal 2: 1, 2011, pp. 1–15.

Saskia Sassen, Territory, authority, rights: from medieval to global assemblages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006); Anne-Marie Slaughter, The chessboard and the web: strategies of connection in a networked world (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017).

John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge, The fourth revolution: the global race to reinvent the state (New York: Penguin, 2014).

The binary terms of raison d'état and raison de système are borrowed from Adam Watson, The evolution of international society: a comparative historical analysis (London: Routledge, 1992).

Freedman, Strategy.

Prantl, ed., Effective multilateralism.

Richard Haass, ‘The case for messy multilateralism’, Financial Times, 6 Jan. 2010; Michael J. Green and Bates Gill, eds, Asia's new multilateralism: cooperation, competition, and the search for community (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009). See also e.g. Karen J. Alter and Kal Raustiala, ‘The rise of international regime complexity’, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, vol. 14, 2018, pp. 329–49.

Ulrich Beck, Risikogesellschaft (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1986). Translated into English by Mark Ritter as Risk society: towards a new modernity (London: Sage, 1992).

Jeffrey A. Friedman, War and chance: assessing uncertainty in international politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

For example, Shahar Hameiri and Florian Kühn, ‘Introduction: risk, risk management and International Relations’, International Relations 25: 3, 2011, pp. 275–9; Jürgen Haacke, ‘The concept of hedging and its application to southeast Asia: a critique and a proposal for a modified conceptual and methodological framework’, International Relations of the Asia–Pacific 19: 3, 2019, pp. 375–417.

Freedman, Strategy, pp. 607–29; Alister Miskimmon, Ben O'Loughlin and Laura Roselle, Strategic narratives: communication power and the new world order (London: Routledge, 2013); Stacie E. Goddard, Paul K. MacDonald and Daniel H. Nexon, ‘Repertoires of statecraft: instruments and logics of power politics’, International Relations 33: 2, 2019, pp. 304–21.

The lack of complexity-informed thinking about policy alternatives in the literature was highlighted in Kai Lehmann, ‘Unfinished transformation: the three phases of complexity's emergence into International Relations and foreign policy’, Cooperation and Conflict 47: 3, 2012, pp. 404–13.

We use complex systems insights as a starting point to develop more suitable diagnostic and policy tools. Our aim is neither to theorize international order using a complex systems model, nor to contribute new empirical cases to the complexity science literature. For surveys of complexity applications in IR, see Emilian Kavalski, ‘The fifth debate and the emergence of complex International Relations theory’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs 20: 3, 2007, pp. 435–54; Amandine Orsini, Philippe Le Prestre, Peter M. Haas, Malte Brosig, Philipp Pattberg, Oscar Widerberg, Laura Gomez-Mera, Jean-Frédéric Morin, Neil E. Harrison, Robert Geyer and David Chandler, ‘Forum: complex systems and international governance’, International Studies Review 22: 4, 2020, pp. 1008–38.

The high degree of connectivity between the individual components of a complex system.

There is a fundamental disproportionality between cause and effect; minor events may create tipping points with major effects (e.g. the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 and the subsequent onslaught of the global financial crisis).

New phenomena emerge from the interactions of the individual components of a complex system; the whole system is more than the sum of its parts.

Ian Goldin and Mike Mariathasan, The butterfly defect: how globalization creates systemic risks, and what to do about it (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014).

These three points are derived from Jervis, System effects, ch. 2.

John H. Miller, A crude look at the whole: the science of complex systems in business, life, and society (New York: Basic Books, 2015), p. 4.

Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in systems: a primer (London: Earthscan, 2008), p. 88.

The strategic narratives point is derived from Lawrence Freedman, Strategy, pp. 607–29.

Jochen Prantl and Evelyn Goh, ‘Strategic diplomacy in northeast Asia’, Global Asia 11: 4, 2016, p. 8.

See our earlier efforts in Jochen Prantl and Evelyn Goh, eds, Global Asia 11: 4, 2016, special issue on ‘Strategic diplomacy in northeast Asia’; and Evelyn Goh and Jochen Prantl, ‘Why strategic diplomacy matters for southeast Asia’, East Asia Forum Quarterly 9: 2, 2017, pp. 36–9.

On the importance of expanding our toolkits to navigate complexity, see Young, Governing complex systems, pp. 223–9.

Meadows, Thinking in systems, p. 97.

Jochen Prantl, ‘Reuniting strategy and diplomacy for twenty-first century statecraft’, Contemporary Politics, vol. 27, 2021, ahead of print, pp. 1–19.

For a detailed example, see the discussion of twelve places to intervene in a system in Donella Meadows, Leverage points: places to intervene in a system (Hartland, VT: Sustainability Institute, 1999).

For example, a strategy of containment aims to trigger negative feedback effects in preserving the pre-existing relative distribution of power, whereas the fear of falling dominoes is rooted in the expectation that even the loss of one peripheral state can trigger a positive feedback loop and tip the system in favour of the enemy ideology. See Jervis, System effects, ch. 4.

Princeton psychologist Daniel Kahnemann argues that the human ability to read situations and grasp strategic opportunities is generated by fast and intuitive ‘System 1’ thinking that is prone to cognitive biases if untrained. System 1 thinking needs to be checked by slow and calculating ‘System 2’ thinking, especially in complex and unique situations. See Daniel Kahnemann, Thinking, fast and slow (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011).

On the potential of a resilience approach to international politics, see Philippe Bourbeau, On resilience: genealogy, logics, and world politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018); also Goldin and Mariathasan, The butterfly defect.

On the implications of complexity for public policy, see Homer-Dixon, ‘Complexity science’.

W. Brian Arthur, ‘Complexity and the economy’, Science 284: 5411, 1999, p. 108.

The diplomacy and statecraft that led to Germany's unification in 1990 illustrates this point. See Jochen Prantl and Hyun-Wook Kim, ‘Germany's lessons for Korea: the strategic diplomacy of unification’, Global Asia 11: 4, 2016, pp. 34–41.

On self-organizing complex systems, see Meadows, Thinking in systems, pp. 159–61.

See the critique in Steve Chan, Thucydides' trap? Historical interpretation, logic of inquiry, and the future of Sino-American relations (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2020).

For a detailed analysis, see Evelyn Goh, ‘Contesting hegemonic order: China in east Asia’, Security Studies 28: 3, 2019, pp. 616–44.

Felix Heiduk and Gudrun Wacker, From Asia–Pacific to Indo-Pacific: significance, implementation and challenges, SWP research paper no. 9, July 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2020RP09/#fn-d24663e272.

On the three phases of the Indo-Pacific concept's development since 2007, see Kai He and Huiyun Feng, ‘The institutionalization of the Indo-Pacific: problems and prospects’, International Affairs 96: 1, 2020, pp. 149–68.

Rory Medcalf, Contest for Indo-Pacific: why China won't map the future (Melbourne: La Trobe University, 2020).

This discussion is drawn from Goh, The Asia–Pacific's ‘age of uncertainty’.