The House of His Desires

The life and legacy of al-Hallaj.

Monday, October 31, 2022

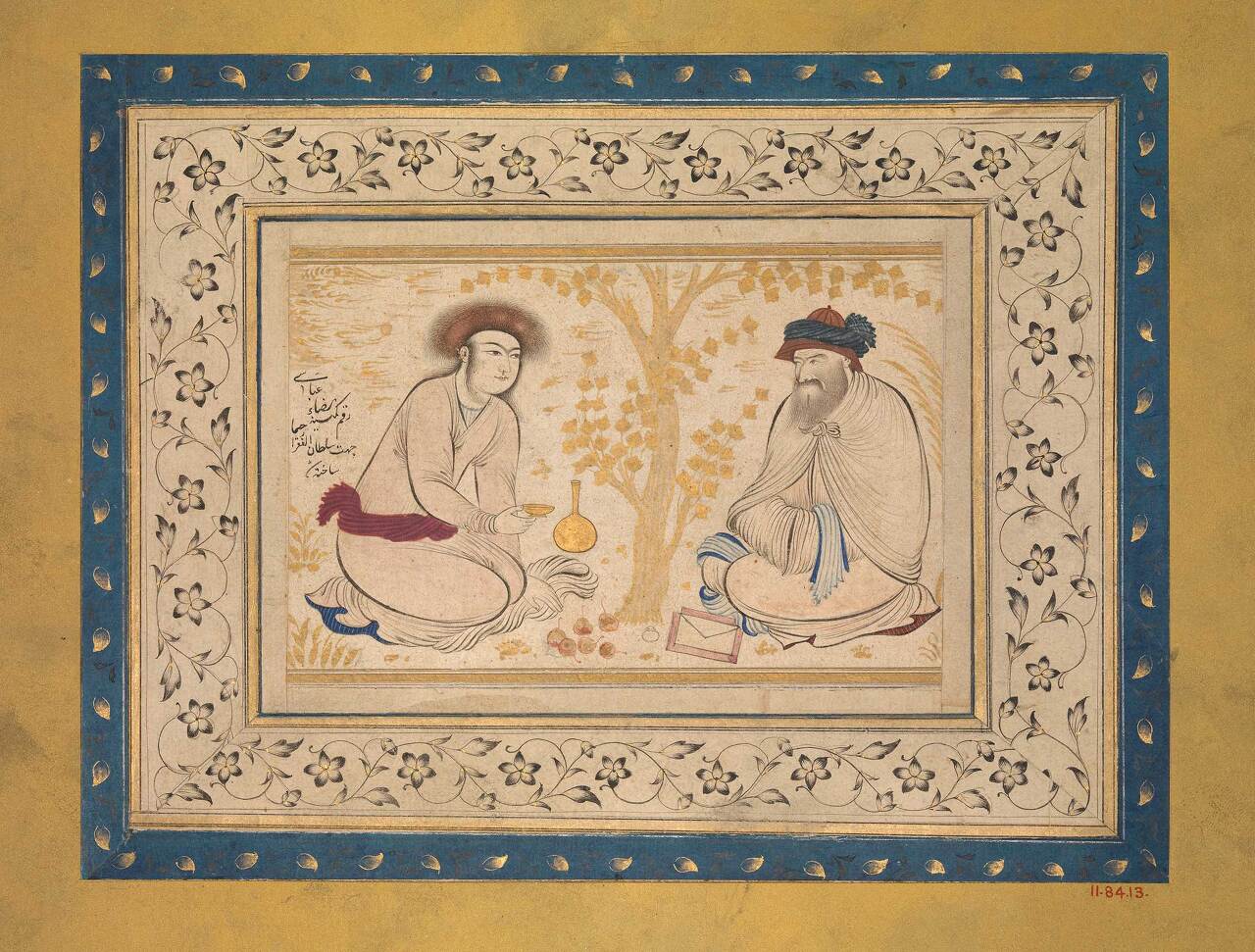

Youth and Dervish, Iran, seventeenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1911.

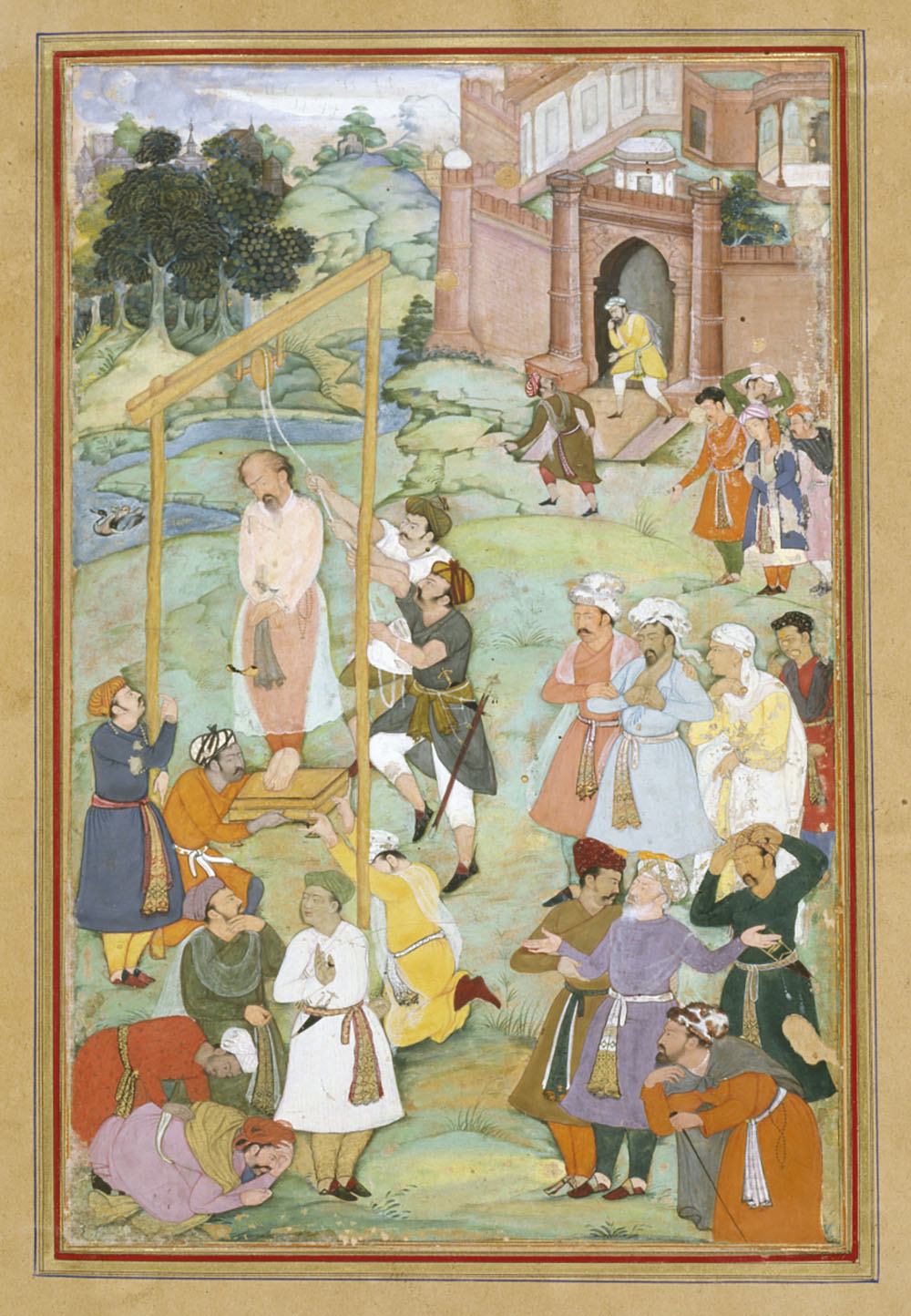

On a spring night in tenth-century Baghdad, a mob gathered to watch as a sixty-four-year-old man, plainly dressed and rail-thin from nine years spent in the city’s dungeons, was bound to a scaffold and raised over their heads. “My God,” the condemned man cried, “I am now in the house of my desires!” In the crowd were gleeful enemies, sympathizers, and fanatics who wanted to witness a miracle.

“What is Sufism?” asked one believer, eager to hear the man’s take on Islam’s mystical path.

“The start of it you are seeing here,” he supposedly replied, “and its end you will see tomorrow.”

His exposure on the gibbet lasted all night. It was a proud moment for the corrupt vizier Hamid and his backers, who wanted to crush the man and reformers like him. The next day, the doomed man was whipped a thousand times, dismembered, beheaded, and then cremated, after which his ashes were chucked into the Tigris. His head was displayed on a bridge in Baghdad, then marched around his Iranian homeland. All who chafe at the ruling powers, the traveling head seemed to warn, should consider the alternative.

The man was Husayn ibn Mansur al-Hallaj, the Persian-born preacher and poet. He wrote poetry and did miracles in public while his prosecutors, led by Hamid, were siphoning tax money and spending it on wine and women; the contrast gave reformers plenty to be enraged about. Eager to quash his critics and those they revered, Hamid launched a witch hunt alongside Quran scholar Ibn Mujahid, who favored less flamboyant Sufis like Abu Bakr al-Shibli and Abu Umar ibn Yusuf, a judge loyal to the caliph. Their campaign went better than they could have hoped. Al-Hallaj’s school of thought didn’t last to the present day like other Sufi schools, such as the Shadhiliyah order, which still flourishes from India to Morocco, or the Mevlevis, founded on the teachings of Rumi and known for its whirling dervishes.

His enemies sent many disciples scattering after blaming al-Hallaj for fomenting various disasters and for spreading bad religion. Al-Hallaj was accused of sparking a Black slave rebellion and a radical Shiite raid on Mecca. His teachings, which presented Satan in a kindly light as God’s true lover, were also found suspect. But attempting to snuff out al-Hallaj’s memory by killing him and persecuting his disciples also made him more memorable and worthy of veneration in the long run. His frequent strange outbursts—shathiyyat, or “ecstatic utterances,” common in Sufism and mysticism overall—were amassed by his students and scholars and kept spreading after his death.

Al-Hallaj’s legacy was revived and remixed by the twentieth-century scholar Louis Massignon, who reimagined him as a “Sufi martyr” made immortal by his final moments, an Islamic parallel to the crucified Jesus. Apart from being Christian-centric, this view cherry-picks from history; al-Hallaj was also a spirit guide, a social reformer, and a poet. Yet Massignon’s sensationalism did serve a purpose: it keeps al-Hallaj in the conversation.

But what exactly is Sufism? Al-Hallaj’s nameless disciple was right to ask. Even today experts don’t always agree.

One thing shared by all mystical traditions is a quest for divine connection free of dogmas, pundits, or one’s own ego. Sufism is a specific expression of Islam, drawing from the Quran, religious law, and rituals common to all Muslims but focused on inward religious experience and given to prayer, fasting, and meditation.

The name Sufism comes from the woolen suf cloak, which mortified the flesh like sackcloth, marking entry into the path of discipleship. The Sufi initiate longs for a “taste,” dhawq, of the transcendent. He walks a path, tariqa, marked by various stations, maqamat, leading back to God. Singing and dancing, strict denial of food and shelter, thought exercises like Buddhist koan riddles—these are mysticism’s bells and whistles, flashy but secondary to the path’s true purpose of transforming the human soul.

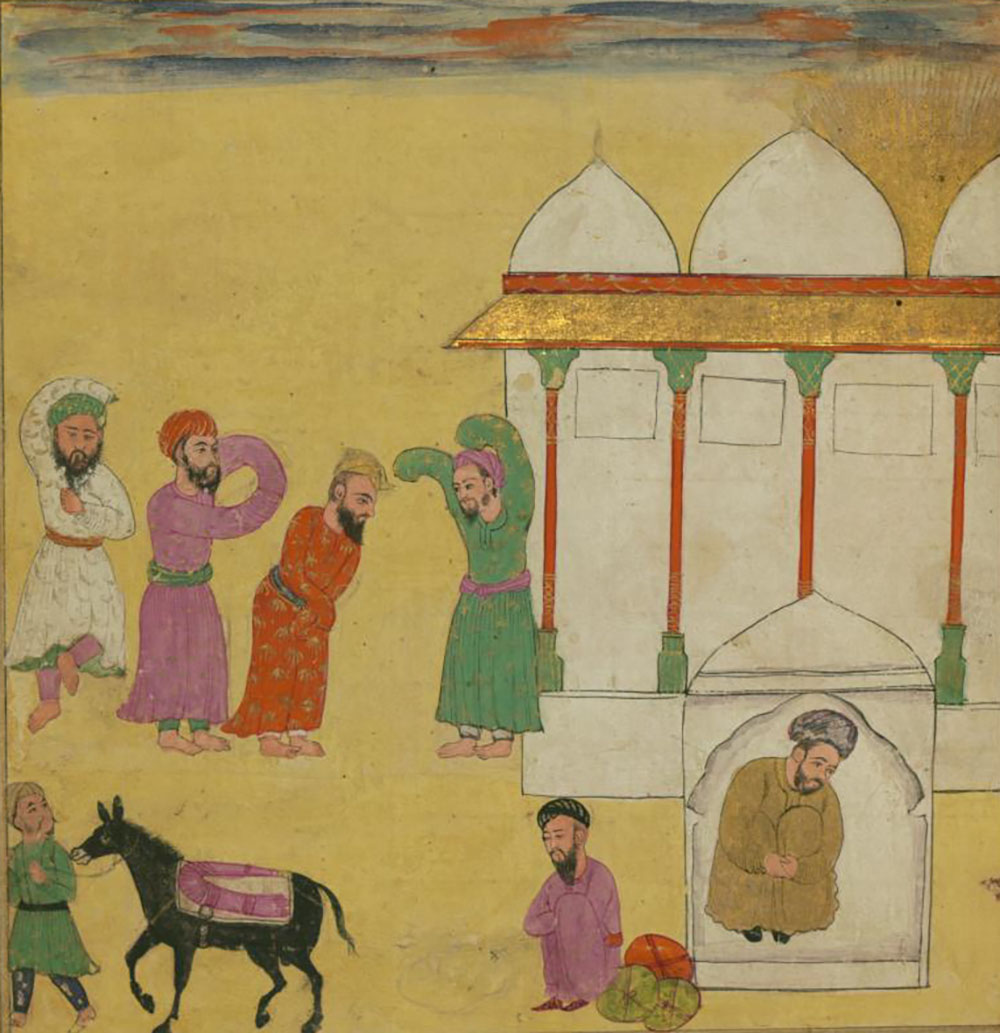

A Dervish, Iran, circa seventeenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913.

Al-Hasan al-Basri (d. 728) and ascetic Rabia al-Adawiyya (d. 801), from Basra in southern Iraq, were magnetic precursors to Sufism, nurturing devotion and worldly self-denial that Sufis from ninth-century Baghdad sought to emulate. At first Sufi teachings spread face-to-face, but over time followers wrote down the words of early masters to create teaching texts and commentaries, speeding up the diffusion. By the twelfth century, Sufism had its own vocabulary, rituals, and lodges, or rawabit, through figures like as-Suhrawardi (d. 1191) and above all jurist and theologian al-Ghazali (d. 1111). Al-Ghazali had a great impact on medieval Latin thought; one of his best-known works, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, criticizes Islamic thinkers like Avicenna (d. 1037) for their fealty to philosophy over revelation. For this reason, al-Ghazali still gets a bad rap for de-intellectualizing Islam in favor of brainless mystical feeling. This stereotype is overblown and was deployed against Sufism writ large. Theologians attacked Sufi beliefs and its practitioners on rationalist grounds, holding that Sufi wisdom meant inner subjectivity—posed against reason—tutored by a charismatic teacher like al-Hallaj.

Sufism flourished at a time when people in Iraq and Iran thought they had compelling evidence that the world was ending. In 861 the caliph al-Mutawakkil was murdered on orders from his eldest son, al-Mustansir. In 869 the Zanj Rebellion, a revolt by Bantu-speaking slaves captured in East Africa and brought to Iraq to drain salt marshes, broke out in southern Iraq. The insurrection lasted fourteen years and claimed thousands of lives before it was suppressed by government troops led by future caliph Abu al-Abbas al-Saffah. These upheavals, which happened when al-Hallaj was still a boy, partly explain why people took refuge in piety, including mysticism, in a quest for meaning in a chaotic world. It also clarifies why they flocked both to and away from a figure like al-Hallaj.

The son of a wool carder, someone who combs and cleans the fibers for processing—hallaj means “carder” or “ginner” in Arabic—the young al-Hallaj moved from his native Fars in Persia to Wasit in eastern Iraq, where he studied with Sahl al-Tustari, a leading Persian mystic who had memorized the Quran by age twelve. It was al-Hallaj’s first brush with Sufism proper, though he had been inclined from a young age to meditate and seek mysteries in scripture. When he was twenty, he went to Basra and married the daughter of a local Sufi. The couple eventually became parents to at least three sons and a daughter.

Al-Hallaj then began studying with Junayd, a Sufi master whose coolheaded, “sober” approach clashed with the ecstatic, “drunk” leanings of al-Hallaj, who was already showing a style of mysticism distinct from al-Tustari. Junayd’s religious teachings required a brush with the ultimate reality, Deity—an instant of oneness with God—but also leaving that moment. Returning to reason, and being able to intellectualize religious ecstasy so that the experience could be shared with followers, was essential. Al-Hallaj did not bother much with regaining sense; he preferred to stay lost in God. Due to these differences, it’s said that Junayd refused al-Hallaj the suf cloak that would have ushered al-Hallaj into the pantheon of masters—those who had trained their bodies and minds to achieve certitude, yaqin, about the nature of ultimate reality through direct vision, and could go on to teach their own disciples. But never earning such a symbol did not stop al-Hallaj from attracting adherents. After finishing his studies and before opening his ministry, he made three pilgrimages to Mecca—and was accompanied by some four hundred believers on his second.

Al-Hallaj returned to Baghdad sometime after the year 902, when he was in his late forties, and built a miniature of the Kaaba, the center of the mosque at Mecca and the holiest site in Islam, inside his own house, an act that stunk of idolatry to conservative Muslims. He prayed next to abandoned tombs at night and in the daytime shouted his burning love of God and his desire “to die accursed for his community.” Around this time, having amassed hundreds of followers and as many detractors, al-Hallaj also voiced his signature line: “I am the Truth.” The Truth was an honorific appropriate for a deity, so some interpreted the statement as al-Hallaj claiming to be God. Such a reading gave enemies reason to try him for blasphemy. But this was merely one exhibit in a larger case being built against him, one often reliant on shaky circumstantial evidence.

Al-Hallaj’s brother-in-law connected him to a dissident clan that had backed the Zanj Rebellion. Al-Hallaj’s accusers at his eventual trial, including the vizier Hamid, would later use that link to blame him for the revolt—which had happened when al-Hallaj was a child—and the apocalyptic dread it caused. What al-Hallaj’s preaching did spark was a failed coup in 908 and a stiff backlash from the authorities, who murdered the poet Ibn al-Mutazz after he was installed as caliph by the reformers. A spate of arrests of his disciples and other piety-minded reformers forced al-Hallaj to flee Baghdad. When he returned, he was imprisoned for nine years, meeting with disciples on the few occasions he was briefly let out of his cell.

The political climate was about to get even worse for al-Hallaj. At the court of al-Muqtadir, who inherited the caliphate as an infant, there was a pro-Hallaj faction led by the vizier Ibn Isa, who ended the investigation into al-Hallaj in 913. An anti-Hallaj faction took over after the vizier Ibn al-Furat jailed Ibn Isa and assumed his role in court. Ibn al-Furat’s successor, Hamid, was opposed by many of al-Hallaj’s followers and in retaliation brought charges against him in 922. Al-Hallaj was accused of plotting to destroy the Kaaba with the Qarmatians, an Iranian Shiite dynasty that raided pilgrim routes to Mecca out of a belief that the pilgrimage was a superstition. (Eight years after al-Hallaj’s death, Qarmatian rebels did actually sack the Kaaba.) Hamid’s evidence involved a bit of literary close reading: al-Hallaj had told disciples to “proceed seven times around the Kaaba of the heart,” which his critics uncharitably interpreted as a call away from the ritual surrounding the actual Kaaba. Convicted of blasphemy and being a public menace, al-Hallaj received a notably harsh sentence. The vizier Hamid wanted to make an example of him and paraded his dismembered head around the land to do so.

Al-Hallaj’s trial and other torments brought a purge within Sufism. Mystics understandably rushed to the mainstream in order to avoid harassment. In his eleventh-century masterwork The Revival of the Religious Sciences, al-Ghazali linked dominant Sunni theology and ethics with mystical thought. For example, to the Sunni orthodox idea that Muslims should emulate only the Prophet Muhammad and no other teacher, al-Ghazali added the mystical notion of “disciplining the soul,” riyadat al-nafs, whereby influences from others must be checked through rigorous training to cultivate virtue. But earlier Sufis like al-Qushayri and Abu Talib al-Makki had been well on their way to such a synthesis—and seen the price of a more feverish Sufism in al-Hallaj’s charred remains.

Even so, for a short time al-Hallaj’s teachings were passed down through the Hallajiyya order, listed as an apostate group by the eleventh-century scholar Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi in his Differences Among the Sects. The posthumously collected Sketches of al-Hallaj is a secondhand record of what he said and did; his last words are among the included utterances. His poetry collection, or diwan, brought to life his union with the Absolute. Much of it speaks to a lover who stands for Deity, as in al-Hallaj’s best-known poem, “I Saw My Lord”:

I saw my Lord with the eye of the heart:

I said, Who are you? He answered: You

Thus where has nowhere, as from you

Nor is there, as to you, a where.

Al-Tawasin, another posthumously assembled verse work, is much stranger. It has eleven chapters, some with diagrams and symbols standing for mystical visions that words can’t express. The longest chapter features a conversation between God and Lucifer—called Iblis in Islam, likely from the Greek diabolos—who appears as a “tragic lover,” the intimate of Deity and the one true monotheist, since in the Quran he refuses to worship anyone other than God, even when ordered to bow before the newly formed Adam. This Miltonic Satan avant la lettre talks with God but also Moses, Pharoah, and Muhammad, affirming Iblis’ commitment to Deity:

He [Iblis] was told: “Bow down!”

He said, “To no other!”

He was asked, “Even if you receive God’s curse?”

He said, “It does not matter. I have no way to an other-than-you. I am an abject lover.”

These daring scenes have led some thinkers to put al-Hallaj together with as-Suhrawardi and the Sufi thinker Ayn al-Qudat al-Hamadhani (d. 1131) in an ahistorical trio of “Sufi martyrs” that overhypes their deaths and forgets their teachings. Ayn al-Qudat focused on the idea of divine love and was executed at age thirty-four for loudly condemning corruption by the Seljuqs, the Turko-Persian Sunni empire under which he lived. As-Suhrawardi thought of mysticism as a “science of lights,” using Plato’s notion of ideal forms, and was put to death by Saladin for having too much influence over his heir. Labeling all three men dissidents and martyrs does not unify their thought into a single strain of Sufism.

The Hanging of Mansur al-Hallaj, India, 1602. The Walters Art Museum.

For much of the late twentieth century, scholars saw al-Hallaj through the sepia lens of Louis Massignon, who also framed al-Hallaj as a martyr. A French scholar of Islam and an advocate for Christian-Muslim interfaith relations, Massignon smoothed the way for the Vatican II declaration that affirmed the Catholic Church’s respect for non-Christian religions and embraced “all which is true and holy in these religions.” Massignon’s four-volume study The Passion of al-Hallaj—even the title betrays Christian echoes—shaped how people saw al-Hallaj’s life and legacy for decades, mingled as it is with Massignon’s own religious commitments. For him, al-Hallaj was an echo of Christ, a truth teller in a world that rejected him. At one point in his research, Massignon even claimed to see al-Hallaj standing next to a crucified Jesus in a beatific vision. Due to such naked Euro- and Christian-centrism, scholars still label Massignon an apologist for Western culture while praising his learned sensitivity. Many Catholics tarred him as a syncretist, a “Catholic Muslim” who lived too close to his work and who mixed the two creeds willy-nilly, although Pope Pius XI praised him for doing just that. In turn, some Muslims thought Massignon fixated on Islam’s margins and forgot its laws, though Edward Said argued in Orientalism that Massignon’s obsession with al-Hallaj let him discuss “values essentially outlawed by the mainstream doctrinal system of Islam, a system that Massignon himself described mainly in order to circumvent it with al-Hallaj.”

Thinkers like Michael Sells and Carl Ernst have rightly made al-Hallaj a subtler figure. Massignon’s vision of a messianic martyr simplifies a man who was also a preacher, a poet, a reformer, and, for some people, a wayward and confused Sufi. The reasons for his trial and execution go far beyond the alleged blasphemy of his ecstatic utterance “I am the Truth.” Yet his words lose their power when scholars downplay them. The very shock and drama of these moments is what makes them stick. Would we be fighting over al-Hallaj, and in the process considering what he had to say, if he’d been less of a showman? Would he still be in our history books without his outrageous blasphemies? Even in his own time al-Hallaj saw the value of a good performance. “O you who blame me my love for Him,” he says in a poem where he assumes the role of the abject lover addressing those who criticize his devotion, “How harsh you are! / If only you knew how I’ve been enriched by Him, / you’d blame me no more.” Far from staining one’s honor, maybe such blame, and even condemnation for loving God too intensely and too publicly, was just the thing al-Hallaj wanted.

Contributor

Kevin Blankinship is a professor of Arabic at Brigham Young University and a contributing editor at New Lines magazine.

'이슬람 世界' 카테고리의 다른 글

| UAE 지폐 속 대한민국 원자력발전소, 무슨 뜻인가 (0) | 2022.12.14 |

|---|---|

| 한국서 히잡 안쓰고 경기했다고...“이란 선수 집 강제 철거 당했다” (0) | 2022.12.04 |

| Who Was Mahsa Amini? (0) | 2022.10.25 |

| Watch 100 Years Of Iranian Beauty In One Minute by memolition (0) | 2022.06.03 |

| Across the Muslim World, Islamism is Going out of Vogue (0) | 2022.01.23 |