What’s in a name? That depends. For dinosaur fans, one hint comes from the passionate fight over what to call that plant-eating giant of the Jurassic age – ‘Brontosaurus’ or ‘Apatosaurus’. Were these beasts reptiles or birds? Two species or one? Something as straightforward as the name of an extinct species may feel like scaffolding for the present day – until the framing crumbles, and another name and alternative view of the deep past takes hold. Nowhere is the dynamic more visible than in the debate over the Brontosaurus. Changing a name changes the world. Unless it doesn’t.

The celebrated palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould chose sides in the heated debate in ‘Bully for Brontosaurus’ (1991), the keynote piece in a book of the same name. Gould covered the outrage over the printing of a stamp by the United States Postal Service labelled ‘Brontosaurus’. Most palaeontologists preferred ‘Apatosaurus’ but, Gould argued in defence of the Postal Service, ‘Brontosaurus’ had permeated public consciousness. Still, for Gould, neither name mattered when it came to what each was naming. Both referred to the same sauropod that lived in the same Jurassic period on the same planet in our same (stable) world.

Yet, for others, the revision suggested something impossibly cataclysmic – a literal rewriting of the past. In 2011, after Gould’s side lost and the sauropod in question was known by ‘Apatosaurus’, the popular science writer Bethany Brookshire recalled her favourite childhood toy: ‘you can imagine my horror when I found out that it was not a Brontosaurus. It was an Apatosaurus … I didn’t believe it … Brontosaurus was awesome!!! Apatosaurus was for losers.’

For Brookshire and those like her, more than naming rights were at stake. Each name seemed to refer to a distinct animal: ‘My model of Brontosaurus had a smooth chin. Apatosaurus had a floppy chin like a turkey and some sort of fleshy crest.’ Though the details that defined Brookshire’s toys, like dinosaur models generally, were only speculations, they seemed to refer to real parts of real animals that existed in the past in the real world.

What happens to that world when parts of it vanish – or, stranger, when they are revealed to have never existed in the first place? That’s a philosophical question about how words and worlds collide.

The renaming of Brontosaurus was scientific but also narrative, born of a mission to revise the story of the prehistoric world. Like palaeontologists, authors of fiction routinely revise their narratives. They expand them by inventing new stories, some placed in the current moment, others inserted between past events. Some of those insertions reinterpret parts of the past, altering some previous stories. Other revisions start the whole world over, altering all previous stories.

Though the true past is fixed and unrevisable, stories about that past are not. Palaeontologists understand these stories as theories, but their audiences often experience them in the same ways they would experience fictional tales – as narratives that shift with mood and politics and time. It’s as if all the Jurassic’s a stage, and Brontosaurus and Apatosaurus merely players. They have their entrances, exits and re-entrances. In this story, one dinosaur – or maybe two – play many parts.

To understand the history of revisions of our actual past, consider the history of a fictional past – from a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. In A New Hope (1977), the first movie of the original Star Wars trilogy, Luke Skywalker and Han Solo save Princess Leia from the clutches of Darth Vader. In the second movie, its sequel, The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Leia and Han save Luke after his own escape from Vader. The second film expanded the first by detailing later events in the same larger story, or saga.

Literally, Vader was Luke’s father. Metaphorically, he wasn’t

The fourth, fifth and sixth movies, comprising a second Star Wars trilogy, expanded the saga too, but by detailing earlier events instead. Starting with The Phantom Menace (1999), they are prequels, fleshing out details around the skeleton of facts mentioned but not shown in the original three films.

While all expansions of the present are sequels, not all expansions of the past are prequels. Some are retcons, short for ‘retroactive continuity’ – for instance, Return of the Jedi (1983), the final film in the first Star Wars trilogy. Like prequels, retcons reveal something new about the past; but, where prequels fill in details without altering the general understanding of established facts, retcons reveal new facts that reinterpret the stories we have already read or seen.

Here’s how it works in Star Wars. In the original movie, A New Hope, Obi-Wan tells Luke that Vader had killed Luke’s father. In the sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, Vader tells Luke that he was his father. But Return of the Jedi resolves the contradiction: Obi-Wan reveals to Luke that what he had said was ‘true from a certain point of view’. Literally, Vader was Luke’s father. Metaphorically, he wasn’t. The continuity between the first two movies is retroactively established by their retcon.

Luke, Leia and Han are players on the Star Wars stage, their stories expanded or retconned as part of a larger saga. Brontosaurus and Apatosaurus are players on the Jurassic stage, their stories expanded and retconned as part of a larger saga, too.

George Lucas and other Star Wars creators could give audiences front-row seats to their fictional saga, but palaeontologists must craft long-time-ago stories about a period of the actual world that ended before humans existed. Revisions should be expected.

One of the earliest of these factual storytellers, Richard Owen, coined ‘dinosaur’ in his ‘Report on British Fossil Reptiles’ (1842). The term means ‘fearfully great lizard’, and it shaped the interpretation of new discoveries for the next century.

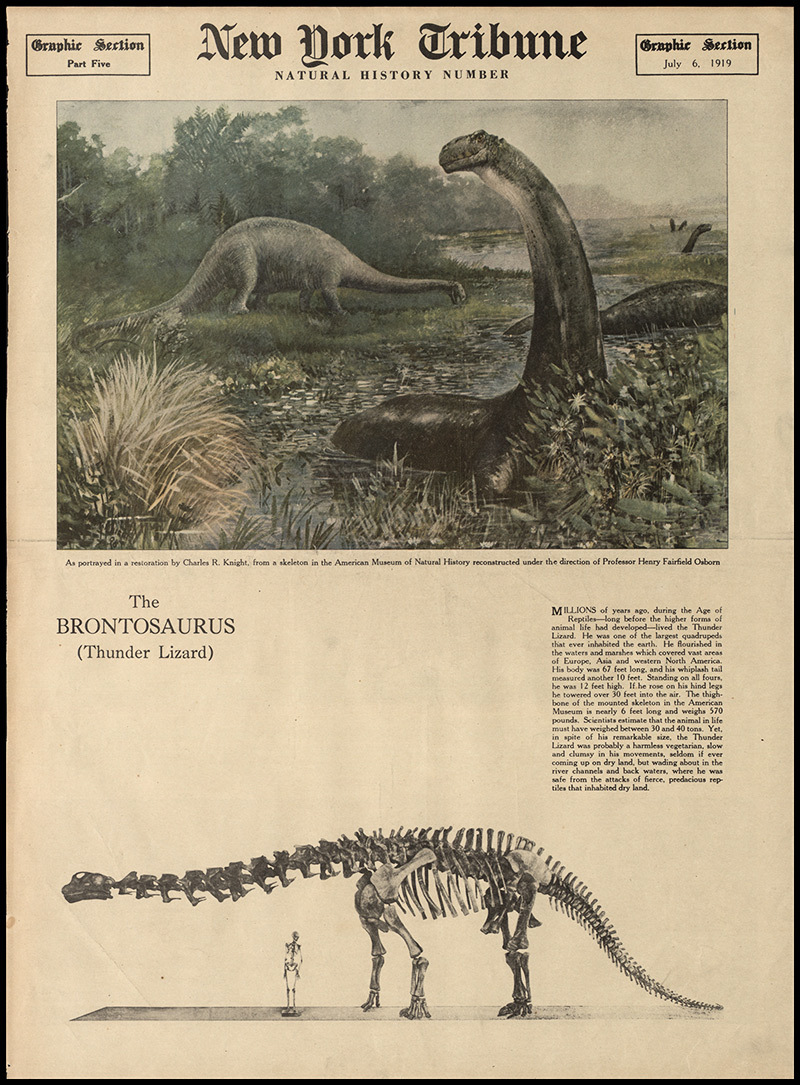

In the 1870s, the palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh of Yale University led summer digs in what was then the Wyoming Territory. When Marsh had his findings published, he described a dinosaur that he named ‘Apatosaurus ajax’. ‘Apatosaurus’ means deceptive lizard, which Marsh chose because the dinosaur had tail bones resembling marine reptiles; he chose ‘ajax’ after the mythological Greek warrior famed for size and might. Marsh also discovered a dinosaur that he named ‘Brontosaurus excelsus’, which he later described:

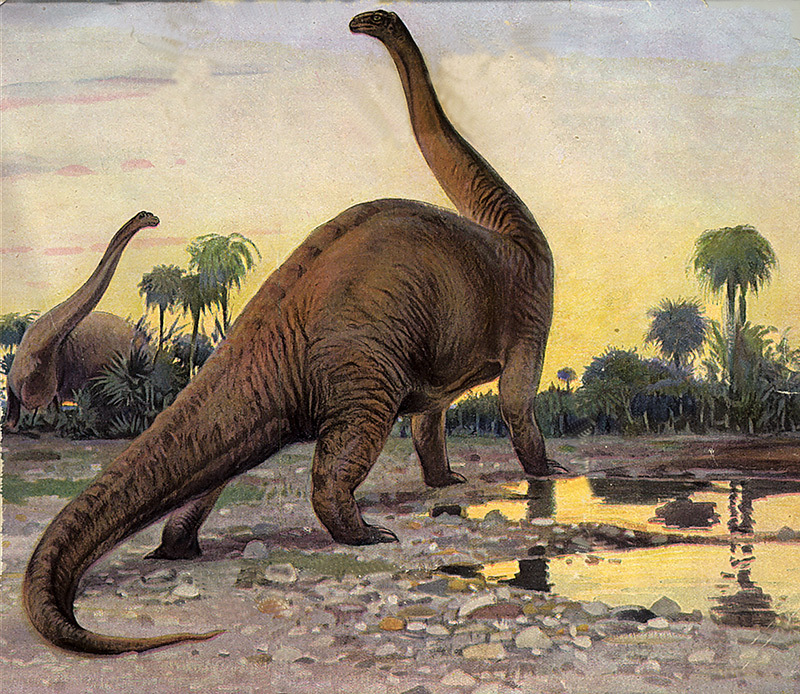

Nearly all the bones here represented belonged to a single individual, which when alive was nearly or quite 50 feet in length … That the animal at times assumed a more erect position than here represented is probable, but locomotion on the posterior limbs alone was hardly possible … The very small head and brain, and slender neural cord, indicate a stupid, slow-moving reptile … The remains are usually found in localities where the animals had evidently become mired.

Though Marsh would discover other dinosaurs, this depiction of a giant, swamp-bound lizard caught the imagination of the general public. The Jurassic saga had one of its heroes. Though Apatosaurus was the first discovered, the public would cheer for its younger sibling, Brontosaurus.

Riggs retconned the claim that the two dinosaurs differed, like Return of the Jedi retconned the earlier Star Wars films

If we understand Marsh as contributing to the overall dinosaur saga, his second article was an expansion of the first. But rather than understanding Brontosaurus excelsus as coming after Apatosaurus ajax, the discovery and report on the second dinosaur was a prequel expanding palaeontologists’ understanding of Wyoming’s ancient past, in the way that the second Star Wars trilogy was a prequel filling in details about the past established in the first Star Wars trilogy. No retroactive continuity came about.

By the time Marsh died in 1899, palaeontologists had endorsed his interpretation; the two sets of skeletal remains belonged to two different dinosaurs, Apatosaurus ajax and Brontosaurus excelsus. But that soon changed. In 1901, Elmer S Riggs, a palaeontologist at the Field Columbian Museum (now the Field Museum of Natural History) in Chicago, unearthed in Colorado what he took as a more complete Apatosaurus skeleton. Comparing it with Marsh’s findings, Riggs wrote: ‘the writer is convinced that the Apatosaur specimen is merely a young animal of the form represented in the adult by the Brontosaur specimen.’

Examining examples of what Marsh had taken as Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus and comparing them with those of the specimen that he himself had unearthed, Riggs concluded that Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus were the same genus. ‘Apatosaurus’ and ‘Brontosaurus’ referred to the same creature, and ‘Apatosaurus’ had priority because Marsh had used the name first. Yet, rather than giving ‘Apatosaurus ajax’ priority in full, Riggs compromised. Combining the genus name for Marsh’s Apatosaurus ajax with the species name for his Brontosaurus excelsus, Riggs called the now-single dinosaur ‘Apatosaurus excelsus’. Marsh’s Apatosaurus ajax and his Brontosaurus excelsus were both Apatosaurus excelsus, or high deceptive lizards.

Words and worlds collided. Though certain elements of Riggs’s article expanded certain elements in each of Marsh’s, by revealing that the two dinosaurs were the same, Riggs retconned Marsh’s overall claim that they differed, much like Return of the Jedi retconned the earlier works in the Star Wars saga.

Metaphysicians, philosophers engaged in the study of reality, largely agree that there’s only one actual reality. The rest are merely possible ones. Nonetheless, they still find it useful to distinguish conceptions of that one reality. Two conceptions are those had by professional science and by popular culture. When it came to dinosaurs, palaeontologists themselves generally agreed with Riggs’s findings and names, but popular displays of the dinosaur preferred Marsh’s names.

In 1905, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City mounted the first complete Apatosaurus excelsus skeleton, labelling it ‘Brontosaurus excelsus’. Adopting Apatosaurus excelsus as its logo, the Sinclair Oil Company presented the Sinclair Dinosaur Exhibit in the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair, featuring a to-scale, green model. Sinclair later presented its Dinoland Pavilion at the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair, featuring an improved 70-foot version. That year, Walt Disney premiered the animated film Fantasia (1940), in which cartoon Apatosaurus excelsus stood in a swamp munching on vegetation to the chaotic beats of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913). The dinosaur’s popularisation was further propelled by other cultural occurrences including Hanna-Barbera’s cartoon television series The Flintstones (1960-66). Yet, while Disney didn’t identify any of the dinosaurs by name, Sinclair and Hanna-Barbera identified their illustrations as Brontosaurus or Brontosaurus excelsus rather than the scientifically preferred Apatosaurus or Apatosaurus excelsus.

These all expanded in popular culture the dinosaur saga from Riggs. They didn’t reveal anything new about something old and already established, even if they happened to retain Brontosaurus or Brontosaurus excelsus. Likewise, in A New Hope, Luke and Han had previously saved Leia, and then, in The Empire Strikes Back, Leia and Han were saving Luke. That was also an expansion, which, by itself, didn’t reveal anything new about something old and already established in the fictional realm.

Regardless of what it was called, the Apatosaurus aka Brontosaurus was long thought to be a stupid, slow-moving reptile.

By the late 1960s, though, things were starting to change again – and not just for Marsh’s and Riggs’s sauropods.

Beginning with an article for Discovery magazine in 1968 and culminating in the book The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction (1986), Robert Bakker retconned the entire Jurassic saga.

Rather than unearthing a new set of bones, Bakker contemplated the array of previous discoveries – and revealed something new about them, something that required a reinterpretation even of the core term ‘dinosaur’.

‘Dinosaur’ was a misnomer, he said; the creatures weren’t ‘sauros’, meaning lizards, but more like birds. And, with that pronouncement, words and worlds didn’t so much collide as veer off course on alternative paths.

Marsh had accepted Owen’s interpretation, expanding it by discovering the fossil remains of animals he assumed were cold-blooded ancestors of modern reptiles. Riggs, though he reinterpreted two of Marsh’s discoveries, accepted Owen’s larger vision too. Bakker revised them all.

‘No one,’ wrote Bakker, ‘either in the 19th century or the 20th, has ever built a persuasive case proving that dinosaurs as a whole were more like reptilian crocodiles than warm-blooded birds. No one has done this because it can’t be done.’

The Smithsonian, alluding to Fantasia and The Flintstones, denigrated ‘Brontosaurus’ as ‘cartoon nomenclature’

This real-world revision is more revolutionary than any fictional one. Luke Skywalker had believed that his father was dead, and that Darth Vader had killed him. Later, he discovered that his father was alive and was himself Darth Vader. His understanding of everyone else remained stable. Bakker instead changed every dinosaur that anyone had ever contemplated. That includes Marsh’s and Riggs’s: ‘Brontosaurs didn’t require deep swamps to buoy their bulk; they didn’t even like to be near swamps.’ Bakker revealed that Brontosaurus excelsus – and therefore Apatosaurus excelsus – had never lived in swamps, as envisioned by both Marsh and Riggs, and as depicted by Disney and others. When anyone had talked about Apatosaurus excelsus (which they often called ‘Brontosaurus excelsus’), they had actually been talking about a warm-blooded, birdlike creature, even if they didn’t know it.

Bakker’s retcon proved popular. In 1989, his colourful revision was featured on a US postal stamp with skin more colourful than the Sinclair model’s swamp-blending green. Palaeontologists objected but not because of its depiction. On the characteristics, they agreed with Bakker. Their chagrin was a response to the stamp’s wording: ‘Brontosaurus’.

Indeed, on nomenclature, they agreed with Riggs. The Smithsonian Institute, alluding to such popular-culture products as Fantasia and The Flintstones – and now this stamp – denigrated ‘Brontosaurus’ as ‘cartoon nomenclature’.

The US Postal Service responded: ‘Although now recognised by the scientific community as Apatosaurus, the name Brontosaurus was used for the stamp because it is more familiar to the general population.’

‘Brontosaurus’ was a fixture of popular culture but, aside from Gould, palaeontologists wanted nothing to do with it. The American Museum of Natural History kept ‘Brontosaurus excelsus’ on its display until 1995 when, 92 years after Riggs’s discovery, it bowed to his nomenclature and Apatosaurus excelsus, too. Attempts to remove the name from the rest of popular culture were slower, though eventually successful. The decision against using the name ‘Brontosarus’ even reached the august news reports of National Public Radio, which in 2012 declared: ‘Forget Extinct: The Brontosaurus Never Even Existed’. That headline was probably sensationalist or at least ambiguous. The story itself said Brontosaurus was not something new. It had always existed as Apatosaurus. Brontosaurus didn’t rise and fall. Only its name did. All of these pop-culture products expanded Bakker’s work. The dinosaur saga expanded without revelation, just as Empire Strikes Back expanded A New Hope.

Palaeontology and popular culture agreed. The two dinosaur players on the stage had been revealed to everyone’s satisfaction to be only one. Philosophy could stand back, describe the word-world scene, and move on.

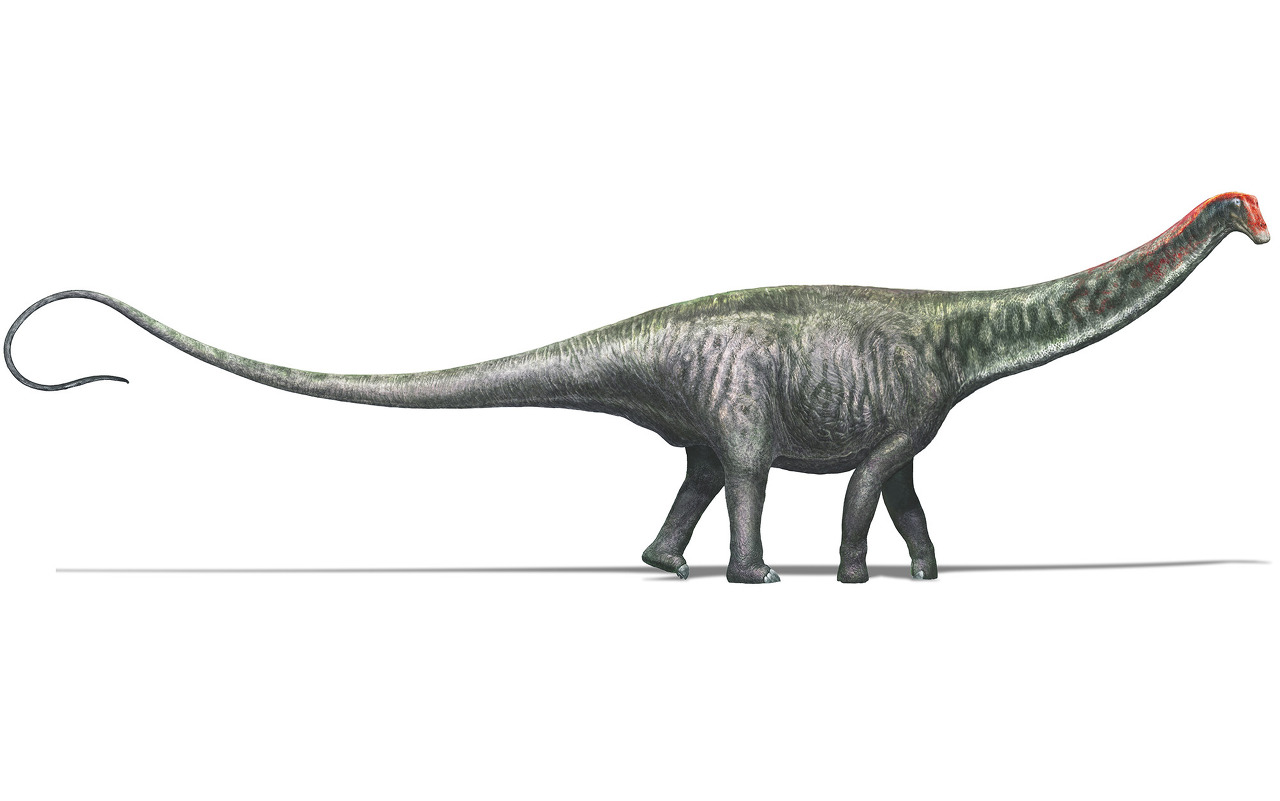

But not for long. In 2015, just a few years after the matter seemed settled, the palaeontologists Emanuel Tschopp, Octávio Mateus and Roger Benson had a study published arguing that, on classification, Riggs was wrong and Marsh right: Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus were different dinosaurs, after all. Measuring and classifying 81 skeletons with 477 distinct skeletal features – far more than any previous study – they concluded that ‘the famous genus Brontosaurus is considered valid by our quantitative approach.’ Marsh’s Apatosaurus ajax and Brontosaurus excelsus were not the same. Riggs’s Apatosaurus excelsus was itself Marsh’s Apatosaurus ajax, leaving Marsh’s original dinosaurs – now understood, thanks to Bakker’s earlier work, as warm-blooded with avian features.

Most palaeontologists today accept Tschopp, Mateus and Benson’s results. Related species of the Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus genera have also been discovered: Apatosaurus ajax, Apatosaurus louisae, Brontosaurus excelsus, Brontosaurus yahnahpin and Brontosaurus parvus. The first and third were Marsh’s. Insofar as Riggs privileged Marsh’s Apatosaurus ajax, the first was also Riggs’s. Popular culture has caught up too, and more quickly this time. Just months after the palaeontologists published their study, the popular science writer William Herkewitz wrote an article for Popular Mechanics, entitled ‘Brontosaurus Is Back: New Study Says the Dino Is Real After All’ (2015), expanding Tschopp, Mateus and Benson’s work. There were again two players on the Jurassic stage. In the case of Brontosaurus in particular, it had its entrance, exit, and (now) re-entrance.

It’s human nature to revise what we think we know, whether it’s Jurassic creatures or Jedi heroes

In short, Tschopp, Mateus and Benson expanded Bakker’s claim that dinosaurs were warm-blooded and birdlike but retconned Riggs’s retcon of Marsh – revising the initial revision in this part of the dinosaur saga. It would be as if, contrary to Return of the Jedi, Obi-Wan hadn’t spoken metaphorically in A New Hope, and Luke learned in some later movie that Vader wasn’t literally his father.

Palaeontologists track the debate within their discipline, and scholars of popular culture track the debate within theirs. Philosophers, searching for a synoptic view, are particularly well-situated to track both.

And from a philosophical vantage point, this is how things now appear: it’s human nature to revise what we think we know, whether it’s factual, like Jurassic creatures, or fictional, like Jedi heroes. Those revisions take shape in language, as the words we use change. Sometimes, the change expands on what we knew, as in a prequel or sequel. Other times, the change reinterprets it, as in a retcon. When words and worlds collide on the Jurassic stage, changes in words can even seem to cause changes in the world. Regardless, all the world’s a stage, a single place where Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus enter, exit, and re-enter time and again.

Because the play’s (also) the thing, such entrances, exists and re-entrances never stop. The Star Wars saga didn’t end with nine movies. There have been other shows, both live action and animated series, other novels and comics, and other movies – with more of each planned. Likewise, the Brontosaurus debate may have performed its final act, but another equally popular dinosaur now has the spotlight. In March 2022, a team of US palaeontologists had an article published claiming that what had previously been thought of as Tyrannosaurus rex is actually three different species. Then, in July 2022, an international group of scientists published a rejoinder challenging the claim.

The drama of revision goes on.