ASTRONOMERS are fairly sure that Mars was once wet. There is plenty of evidence—from dried-up river valleys to the presence of chemicals that need water to form—to suggest this. Modern Mars, though, is a freezing desert. In the 4.5 billion years since the planet came into existence, a sizeable chunk of its water has boiled away into space, another chunk is thought to have seeped deep into its interior, and what little remains on or near the surface has frozen solid. That is depressing for those who seek Martians, even bacterial ones, for most biologists agree that liquid water is a sine qua non of life.

Some researchers, though, think Mars is not entirely dry. Over the past few years evidence has accumulated that water still trickles over its surface from time to time. And a paper just published in Nature Geoscience by Lujendra Ojha of the Georgia Institute of Technology and his colleagues offers the most convincing proof yet.

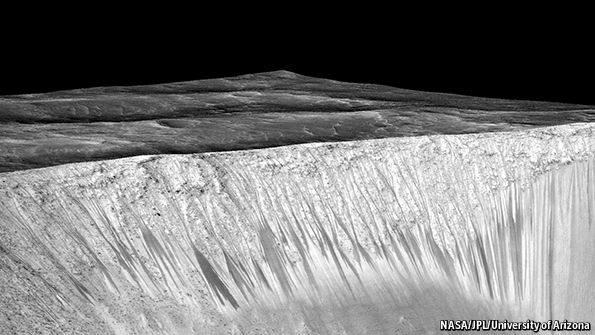

In 2011 Mr Ojha, then a student at the University of Arizona, spotted dark streaks on the walls of certain Martian craters that had been photographed from orbit by a satellite called Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. These, he noticed, seemed to wax and wane with the Martian seasons—darkening in summer and fading in winter. Though he cautiously dubbed the streaks “recurrent slope lineae”, or RSLs, rather than giving them a name that included the “w” word or anything connected with it, he nevertheless suspected that water was their cause.

The surface temperature on Mars does not rise above the freezing point of pure water, but Mr Ojha suspected that chemicals in the regolith (the crushed rock that passes for soil on Mars) act as antifreeze, depressing the freezing point of brine containing them to one which, at least in summer, permits that brine to stay liquid. The summer darkening of the RSLs, he thought, was caused by such brine flowing. The winter lightening, conversely, was caused by it freezing again. Rough-and-ready modelling suggested the streaks were growing and fading at approximately the right rate for this hypothesis to be correct.

Mr Ojha’s latest paper examines the question in detail. He and his colleagues used spectroscopy to examine RSLs in four different parts of Mars. This technique permits researchers to determine a substance’s composition from the light it reflects. The results suggest the streaks contain compounds (specifically, magnesium perchlorate, magnesium chlorate and sodium perchlorate) that are excellent antifreezes, and would be able to lower water’s melting point by more than 70°C. That would be enough for ice containing them to melt in the Martian summer. Moreover, all of these substances form by the action of water on other minerals, bolstering the case that the RSLs are intermittent streams.

Mr Ojha is careful to point out that he has not detected water directly, and that even what he has detected is at the limits of what Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter can accomplish. But the presence of compounds that need water to form, as well as acting as antifreezes, is powerful indirect evidence. The case for there being liquid water—or, at least, brine—on modern Mars has thus become stronger.

Details remain to be worked out, including where the water in question originates. Possibly, it derives from subsurface ice. Or it might condense out of Mars’s thin, dry atmosphere. Wherever it does come from, though, the amounts in question are modest in the extreme. But even modest amounts of water are intriguing to biologists. If Martians evolved during their planet’s earlier, wetter phase, the continued presence of water means it is just about possible that a few especially hardy types have survived until the present day—clinging on in dwindling pockets of dampness in the way that some “extremophile” bacteria on Earth are able to live in cold, salty and arid environments.

Looking for Martians will be harder than looking for water, for spotting bacteria from orbit is beyond the capabilities of any space probe that engineers know how to build, and even analysing samples on the surface is fraught with difficulty. But, buoyed by the success of Curiosity, a car-sized rover that has been trundling over the Martian surface since 2012, NASA is planning a follow-up mission, which should arrive in 2020. Expect some RSLs to be top of the list for scrutiny.