The intimate Michelangelo

by James Hankins

The New Critgerion

December, 2017

Fame often does an artist little good. Quite apart from the moral temptations, there is the danger of sticking with what works, closing oneself off to new ideas, refusing new challenges, becoming a brand. In Michelangelo’s case, fame’s ill effects, limited in his lifetime, in the long run turned disastrous. To be sure, Michelangelo never let success freeze his creativity; he remained brilliantly creative down to the end of his long life. But once he had achieved his place in the world of Renaissance art, he confined his creative energies within rather strict guiderails. He stopped taking certain risks. After some youthful experiments, he showed little stylistic development, and almost none in his last fifty years (he lived to eighty-eight). He clung to the techniques he had learned in his youth. Unlike his older contemporary Leonardo da Vinci, he was no experimenter when it came to artistic media. His longtime collaborator Sebastiano del Piombo, trained in the latest Venetian techniques of oil painting, tried to push him into experimenting with the new medium. A fascinating exhibition earlier this year at London’s National Gallery, “Michelangelo & Sebastiano,” traced the interaction of their partnership over two decades. Michelangelo clearly respected his younger partner’s skills in oil but never tried to master the medium himself, remaining wedded to the traditional Florentine techniques of fresco and painting on panel with egg tempera. The lines of influence in their collaboration went in only one direction. When in 1536 Sebastiano tried to nudge him in the direction of oil by having the incrostatura for the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, without the older artist’s knowledge, prepared for oil painting a secco, that was the end of their friendship. In anger Michelangelo denounced oil painting as an art “fit only for women and lunatics.” He ordered the offending surface stripped off and replaced with plaster over brick, so that he could use the fresco technique he had learned from his teacher Ghirlandaio a half-century before. It was the same technique that he had used to paint the Sistine ceiling from 1508–12. He was still using it in 1545. But Sebastiano was right: the future of European art lay in oil painting on wood and canvas, not fresco.

The real disaster caused by the fame of Michelangelo, however, occurred after his death. After Leonardo da Vinci passed from the scene in 1519 and Raphael died a year later, Michelangelo was left in undisputed possession of Olympus: he was the greatest artist in the world. He still heads many lists as the greatest artist in Western history. He lived at a time when the power of art was respected as never before or since; his services were sought out, indeed fought over, by popes and princes. He was canonized as the supreme artist in the first history of Western art, Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (1550), which gave him the epithet divino. His position has been unassailable in part because he created unforgettable monuments in sculpture, painting, and architecture: three major art forms. This is a claim that can be matched by no other artist. For centuries now his sound has gone out into all lands and the peoples of the earth have made pilgrimage to see his works in the flesh, in Italy. The sad result has been to make his major paintings, all in the Vatican Palace, nearly unviewable, and certainly not viewable in the way that Michelangelo intended. Nowadays visitors who want to look at Michelangelo’s frescos in the Sistine Chapel and the Capella Paolina, unless they can pull strings and get a private viewing, will be frog-marched through the Vatican Palace amid a chattering throng of selfie-snapping tourists, pushed along between velvet ropes at a rapid walk, looking neither to the right nor to the left, until they reach the Sistine. There they will descend to join a seething mob whose subdued roar is only intermittently stilled by a guard with an amplified megaphone, demanding, with comic incongruity, “Silenzio!” Michelangelo’s art is supremely contemplative, intended to elevate the soul to the sublime and the sacred, but now his finest work is usually glimpsed over bobbing heads amid an infernal hubbub.

A delightful alternative to the Michelangelo experience of mass tourism is being offered this winter at the Metropolitan Museum.1 It is an exhibition of his drawings, the largest ever mounted, brought together from over fifty lenders by the eminent art historian and Met curator Carmen Bambach, who is also among the greatest living connoisseurs of Renaissance drawings. If you can choose a quiet morning to wander through “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman & Designer,” you will have a far more unhurried, contemplative experience of this profound and brilliant master than you will find in the Vatican. The purpose of the exhibition is to take us into Michelangelo’s creative world, to show us how he developed the ideas for his major commissions: from initial sketches that aim to reimagine old myths and Bible stories; to compositional drawings exploring arrangements of figures against backgrounds; to more finished drawings that work out difficult details; and finally to cartoni, large assemblies of folio sheets used to scale up designs for transfer to their permanent supports. In short, the exhibition focuses on disegno, a word meaning both drawing and design. For Michelangelo, disegno above all meant the search for expressivity, beauty, and nobility. It is Michelangelo’s transcendent genius in disegno, Bambach argues, that underlies his achievement in all three of the arts he practiced. Michelangelo’s brilliance lay in his endlessly imaginative skill in provoking complex emotional and spiritual responses in the viewer, primarily through the vocabulary of the human form.

So the exhibition takes us into Michelangelo’s studio, and as we pass from room to room we follow his pen and chalk as he thinks through the challenges offered by the various commissions he has accepted. We start with the Florentine atelier of his master Domenico Ghirlandaio, where the young Michelangelo learned to draw and paint, and we can admire the sort of precise and difficult silverpoint drawing he was taught in his youth, as well as kindred works created by his fellow apprentice Francesco Granacci, who remained a lifelong friend. We then pass to the sculpture garden of the Medici, presided over by the elderly Bertoldo di Giovanni, where Michelangelo learned the art of carving marble with the gentle encouragement of Lorenzo de’ Medici, his first patron. We see him copying works of two great Florentine masters of the recent past, Masaccio and Donatello. Then we enter the period of his first great commissions: the Pietà (1498–99), the David (1502–04), and the Battle of Cascina (1505). This last (for which Michelangelo completed only the cartoni, now lost but attested in copies) was to have been a large-scale patriotic painting to decorate the walls of the Sala del Cinquecento in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of her republican government. on the opposite wall another famous Florentine battle, the Battle of Anghiari, was to be painted by Leonardo da Vinci. He too was developing his cartoni at precisely the same time. It was the rivalry with Leonardo that stimulated to the highest pitch Michelangelo’s obsessive interest in the adult male nude and its expressive potentiality. From that time forward, he would leave behind the beautiful but relatively anodyne style, based on classical and early Quattrocento models, he had previously pursued. From then onwards the ambition took hold of him to expand vastly the vocabulary of the human form, inventing new poses expressive of an infinite range of emotional and spiritual states, from figures that embodied pathos, tragedy, and defeat to figures of supreme energy, lordship, and sublimity. In parallel with Leonardo’s search to express the inner thought, Michelangelo developed an ability to express character through form and features: strength and weakness, innocence and shame, the noble and the ignoble, grief and pious hope.

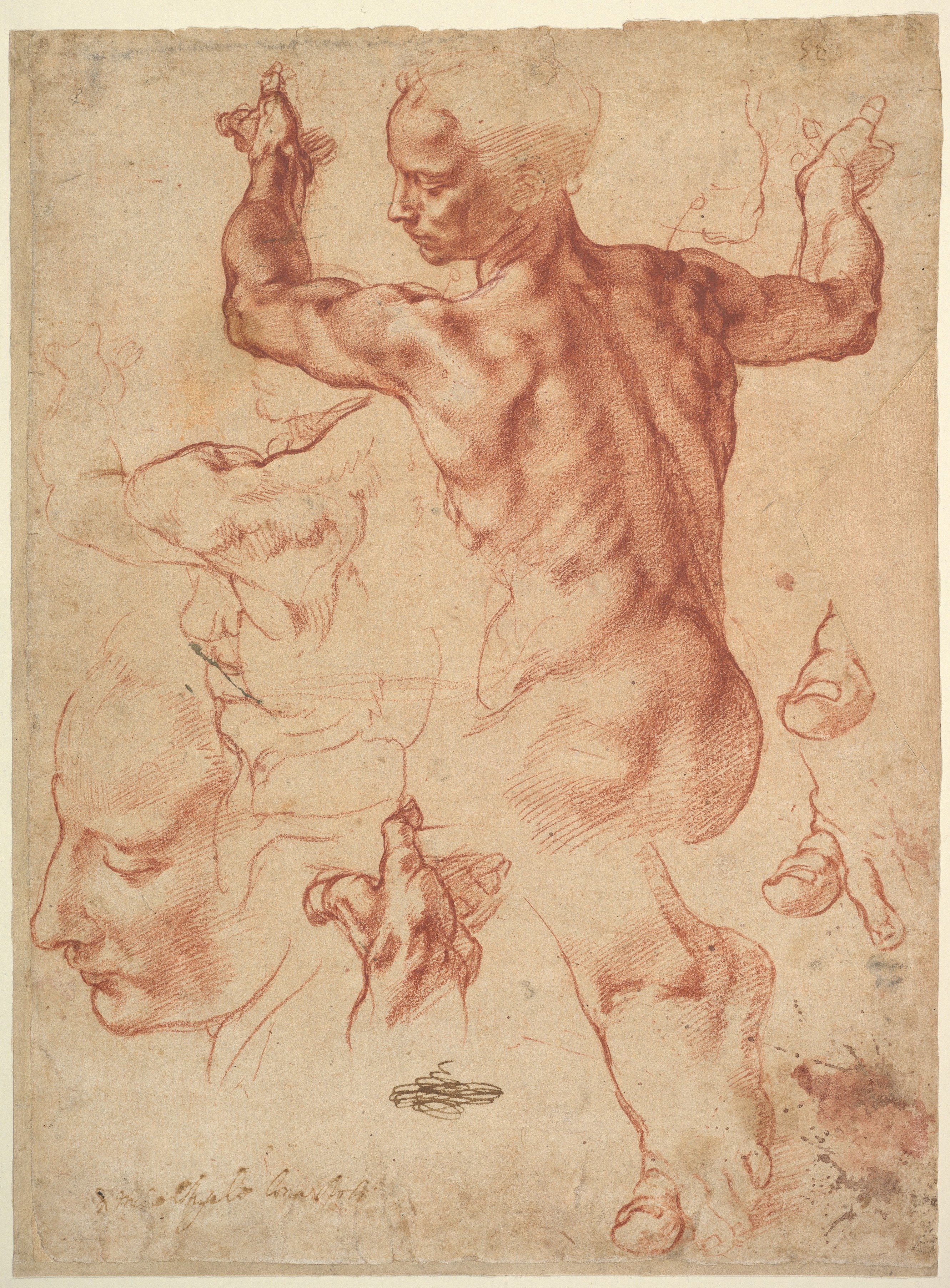

The heroic scale of Michelangelo’s artistic ambition first revealed itself on the vast ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which disclosed to an astonished world the new expressive possibilities achieved through mastery of disegno. Artists were quick to use the ceiling as a school of anatomy; its figures were probably the single most widely copied work by European artists during the centuries dominated by the old masters, down to the early nineteenth century. The exhibition boasts twelve of Michelangelo’s studies for the ceiling, including the most delectable drawing in the show, the Met’s own sheet of studies for the Libyan Sibyl. As the drawings clearly indicate, the Sistine ceiling was closely linked in Michelangelo’s artistic imagination with his other great commission from that time, the monumental tomb of Pope Julius II. The project went through at least three major design phases, all documented in the exhibition, but at its most pharaonic it was to have been a free-standing, three-story architectural armature ornamented by as many as forty-seven figures in Carrara marble. The project, described by Michelangelo’s biographer Ascanio Condivi as “the tragedy of the tomb,” was to dog him for forty years—until the final, unsatisfactory installation was put together in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli around 1545. It bears little resemblance to what either Pope Julius, his heirs, or Michelangelo himself wanted, but the rather tawdry compromise, much of it not by the master’s hand, is redeemed by what many regard as Michelangelo’s greatest achievement in sculpture, the statue of Moses. (To play the cicerone for a moment, let art lovers in search of quiet communion with Michelangelo note that the place is almost untroubled by tourists, intent as they are on infesting the Colosseum at the bottom of the hill.)

The tragedy of the tomb was the result of many factors, including problems with payment and the supply of marble, an ongoing logistical problem that wasted years of Michelangelo’s life. But the real reason for the failure was Julius’s death and Michelangelo’s growing fame. He was now the most sought-after artist in Italy, and his professional life, in the effort to satisfy patrons, became increasingly chaotic and mobile. He began to use more collaborators and assistants to deal with the press of work, much of which remained unfinished, leading to enraged protests and harassing litigation from disappointed patrons. Unfinished marbles began to fill his studio. The rising demands are mirrored in the drawings, which often contain rapid designs for two or three separate projects on a single sheet, leaving an impression of desperate hyperactivity. Michelangelo divided his time, as one would say today, between Florence, Rome, and the quarries of Carrara, pulled and stretched by Medici popes in one city and Medici dukes in the other.

Perhaps partly as a way of protecting himself from the peremptory commands of aristocrats, Michelangelo by the 1520s had set up as a gentleman himself, was addressed as a lord, and cultivated the fine art of penmanship, a mark of the humanistic education he lacked. By this time the artist, in reality the scion of an old but impoverished middle-class family, was claiming to be descended from the eleventh-century counts of Canossa. He no longer signed himself Michelagniolo scultore, and reproved his nephew Lionardo for sending him an artisan’s tool: “You sent me a brass measuring ruler as if I were a plasterer or carpenter who had to take it with me. I was ashamed to have it in the house and gave it away.” Petitioners addressed him as spectabili viro domino or even magnifico viro—the style of his quondam patron Lorenzo de’ Medici. As recipient of major architectural commissions, he acquired more exalted duties as a manager of large projects with numerous assistants. He also began to place increasing emphasis on his role as disegnatore, an ideas-man, whom other artists and patrons could count on for brilliant designs, finishing the merely artisanal tasks of painting and carving on their own. In the “Michelangelo & Sebastiano” show mentioned earlier there is a marvelous portrait of Michelangelo from around 1520, probably by Sebastiano, that shows him, dressed in the white shirt, black tunic, and furs of a gentleman, turned toward the viewer with a grin on his face, pointing to a figure he has drawn in an open book of designs. “Here’s one that might interest you,” he seems to be saying. Clearly Michelangelo no longer wanted to be seen as a man splattered with paint (as in his famous early sonnet on painting the Sistine Chapel), or with marble dust under his fingernails.

Isabella Stewart GardnerMuseum, Boston

The Met show gives us an intimate portrait of this new Michelangelo, the wealthy gentleman-artist who cultivated a circle of noble friends. Michelangelo was regarded as a difficult man by his patrons and rival artists, but in fact he had many warm friendships with family members and associates of various kinds. He also had several romantic but (perhaps) physically innocent relationships with handsome young noblemen. The most famous of these was Tommaso dei Cavalieri, who was probably around seventeen or eighteen when Michelangelo first met him in 1532 at the age of fifty-seven. The older man addressed to him many passionate sonnets that puts one irresistibly in mind of Shakespeare. He also sent his “messer Tomao [Tommy], my dearest lord,” gifts of highly finished drawings, several of which are included in the exhibition. The exhibition is particularly rich in such disegni finiti, and it is these that will probably offer the most pleasure to the casual museum visitor. They are private drawings, meant to be seen only by select audiences or close friends, and thus all the more revealing.

Particularly remarkable is a portrait of another young man, Andrea Quaratesi, the finest of Michelangelo’s few portraits. Vasari tells us that Michelangelo avoided portraiture because he “abhorred making a resemblance true to life, unless [the subject] were of extraordinary beauty.” This has led to the widespread view that Michelangelo’s art celebrates an idealized humanity, and there is surely much truth in that. But the Quaratesi portrait, made ca. 1531–34 when the young man was around twenty, shows that it was not through lack of skill that Michelangelo did not follow Leonardo’s example in portraiture. It was Leonardo who in the Mona Lisa of 1503 had pioneered the type of portrait which suggested the subject’s thoughts by subtle variations of expression and pose, and that is just what Michelangelo does here, with brilliant success. We can’t know what the young man thought of the aging artist, but the sidelong, slightly apprehensive look on his face strongly tempts us to guess.

Despite this pattern of tender friendships with young men, Michelangelo’s deepest devotion in his final years was given to a woman. The lady was Vittoria Colonna, the marchesa of Pescara, the finest female poet of the sixteenth century, described by the historian Paolo Giovio as the most remarkable woman of her age. The close relationship between the two has long fascinated not only art historians but historians of literature and spirituality as well. Vittoria was born into the most prestigious family of the old Roman nobility and had been married young to an accomplished condottiere, Fernando Francesco d’Avalos, whose death in 1525 left her a widow. She remained one for over two decades. Resisting offers of remarriage, Vittoria turned to religion and became the center of a group of spirituali and crypto-Protestant intellectuals, suspected of heresy by more conservative elements in the Church. She also formed a relationship with Michelangelo, which led to a new burst of poetical compositions from the sixty-one-year-old artist, many in praise of Vittoria’s beauty, virtue, and piety. Vittoria responded with poetic gifts of her own, and in fact the most complete codex of her poems, on display here, was a present to her beloved artist friend. The relationship flowered just as Michelangelo was preparing the designs for The Last Judgment, and many art historians have found traces of Vittoria’s ascetic and mystical piety in that final, supreme effort of the artist’s old age.

As with his young men a decade earlier, Michelangelo was now inspired to make more beautiful gift-drawings, this time on severely Christian themes. The two most famous are on display here, a Pietà and a Crucifixion, datable to 1538–41. They are studies in suffering, sacrifice, and resignation to the will of God. It is one of many scholarly contributions of the exhibition that Carmen Bambach is able to associate these images with an epistolary exchange between the two friends, reproduced in its entirety in the catalogue of the exhibition. It should not go without remark that the catalogue of the exhibition is itself a major contribution to the study of Michelangelo’s drawings, containing a monograph-length chronological survey by Bambach herself and five shorter studies by eminent authorities. If the most famous finished monuments of Michelangelo’s artistic career have been overrun by the barbarian hordes of international mass tourism, the paper fragments that remain of his working life and intimate friendships are clearly in excellent hands.

1 “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman & Designer” opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, on November 13, 2017 and remains on view through February 12, 2018.