Forty thousand years ago in Europe, we were not the only human species alive – there were at least three others. Many of us are familiar with one of these, the Neanderthals. Distinguished by their stocky frames and heavy brows, they were remarkably like us and lived in many pockets of Europe for more than 300,000 years.

For the most part, Neanderthals were a resilient group. They existed for about 200,000 years longer than we modern humans (Homo sapiens) have been alive. Evidence of their existence vanishes around 28,000 years ago – giving us an estimate for when they may, finally, have died off.

Fossil evidence shows that, towards the end, the final few were clinging onto survival in places like Gibraltar. Findings from this British overseas territory, located at the southern tip of the Iberian peninsula, are helping us to understand more about what these last living Neanderthals were really like. And new insights reveal that they were much more like us than we once believed.

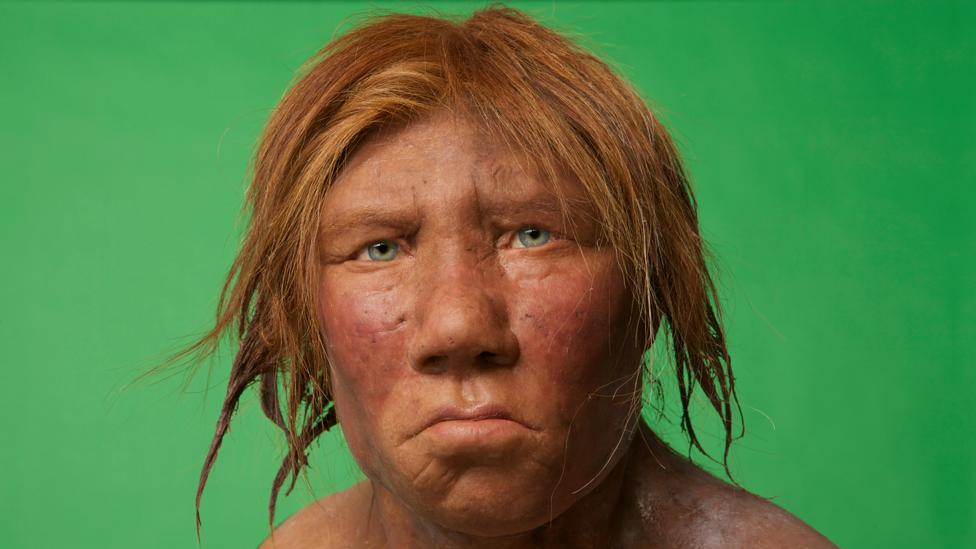

A reproduction of a Neanderthal family on display at the Field Museum of Natural History at Chicago, Illinois (Credit: Getty Images)

In recognition of this, Gibraltar received Unesco world heritage status in 2016. Of particular interest are four large caves. Three of these caves have barely been explored. But one of them, Gorham's cave, is a site of yearly excavations. "They weren't just surviving," the Gibraltar museum's director of archaeology Clive Finlayson tells me of its inhabitants.

You might also like:

- The small list of things that make humans unique

- What killed the Neanderthals?

- Would humans evolve again if we rewound time?

"It was in some way Neanderthal city," he says. "This was the place with the highest concentration of Neanderthals anywhere in Europe." It’s not known if this might amount to only dozens of people, or a few families, since genetic evidence also suggests that Neanderthals lived in “many small subpopulations”.

Their occupation in Gibraltar was first established in 1848, with the discovery of the first fully adult Neanderthal skull. Since then bones of seven other Neanderthal individuals have been found, as well as numerous artefacts they used in their daily lives, such as tools, animal remains and shells.

We can date each discovery based on where it was found. Inside Gorham's cave there are many metres of sediment layers. Each layer depicts a different point in geological time. Fossil remains discovered in these layers suggest that Gibraltar’s Neanderthals occupied the cave on and off for more than 100,000 years.

Neanderthals may have clung on in the region until as recently as 24 to 33,000 years ago, according to the dating of one of the layers in Gorham's cave. This puts this area as one of the last known places where Neanderthals lived.

They may have spread to the surrounding coastal areas too, but the water has risen considerably in the last 30,000 years. This means any other fossil evidence has long been submerged. "We are lucky that in Gibraltar because of its steep cliffs, the evidence has stayed in these caves," says Clive.

Clive, along with his wife Geraldine and son Stewart, has been excavating these caves for many years. All three are scientists.

While the front part of the cave is relatively open, bathed in natural sunlight with a direct view of the ocean, the back is darker and splits off into several chambers. The caves remain cool in the summer and slightly warm in the colder months – a perfect place to rest tired eyes and stay safe from dangerous predators.

Clive Finlayson, the Gibraltar museum's director of archaeology, says Neanderthals could have thrived in Gorham's cave (Credit: BBC Earth)

Kissing cousins

Like the rest of their species, the Neanderthals who lived here were far from what we once pictured – a brutish, stocky group of primitive humans who could only grunt to communicate and violently wield their clubs before anyone who got too close.

In fact, as the University of Colorado Boulder’s Paola Villa put it in a review, they were much like us: we need to dispel "the modern human superiority complex". This is strengthened by genetic insights. Not only do we share 99.5% of the same DNA, we still carry some Neanderthal DNA today.

That’s because when we arrived into Europe from Africa, we met each other several times and interbred with them. All individuals outside of Africa still carry evidence of this prehistoric mingling. I discovered a few years ago that I have 2.5% Neanderthal DNA. There’s a lot of it out there – across thousands of individuals, researchers have identified a combined total of 20% Neanderthal DNA in modern humans today.

Discoveries at Gorham’s cave have helped give us many more insights like these, especially about their last years on Earth.

Remains from the cave suggest that they exploited seafood and marine mammals. This is unsurprising given new evidence published in January 2020 that suggests they could swim. There is even evidence that they hunted dolphins, says Clive Finlayson. How they did so remains unclear, but we do know they hunted – or scavenged – large game like woolly mammoths, woolly rhinos, deer and ibex.

The fossilised skull of a Neanderthal found on Gibraltar is displayed at the Natural History Museum in London (Credit: Getty Images)

The remains of more than 150 different species of bird have also been uncovered in Gorham's cave, many with tooth and cut marks, which suggests Neanderthals ate them.

There is even evidence they caught birds of prey, including golden eagles and vultures. We don't know if they laid out meat and then waited for the right opportunity to go in for the kill, or whether they actively hunted birds, a much more difficult task. What we do know is that they didn't necessarily eat all the birds they were hunting, especially not the birds of prey like vultures – which are full of acid.

"Most of the cut marks are on the wing bones with little flesh. It seems they were catching these to wear the feathers," says Clive Finlayson. They seem to have preferred birds with black feathers. This indicates they may have used them for decorative purposes such as jewellery.

To show me exactly what he meant, Clive and his team reconstructed some intriguing Neanderthal habits. A dead vulture, carefully kept frozen, was brought out and dissected in front of me, to show how Neanderthals might have done so thousands of years earlier.

They carefully removed the bird's body tissue. What was left appeared to be a stunning and elaborate black-feathered decorative cape, extending, of course, the length of the vulture's wing span. They may have wrapped this around their shoulders, Clive says.

Neanderthals could have caught vultures to use their feathers for decoration (Credit: BBC Earth)

This all points to one thing: that Neanderthals had a sophisticated understanding and appreciation of cultural symbols.The fact that Neanderthals could, and would, take these steps – including the creativity and abstract reasoning required to turn a flying animal into a decorative cape – shows that their cognitive skills could have been on par with ours. And regardless of exactly how intelligent they were, their creation of these kinds of cultural artefacts is one of the defining traits of humanity.

Ancient artists

They may even have been producing art. In one surprising 2014 discovery, the Finlaysons found a marking on the wall of Gorham's cave, dubbed the "Neanderthal hash tag". This was the first evidence of Neanderthal art, Geraldine says.

Despite its crudity, Geraldine assures me that lots of preparation would have gone into it. "It wasn’t something that happened by a mistake or as a result of a doodle… some thought process was going on," she says.

When archaeologists tried to re-make the design themselves, they found that the deepest groove required 60 strokes of a sharp stone tool. "It was clear it was something intentional,” Geraldine says.

Further discoveries of decorative shells and the use of red ochre pigment at Neanderthal sites also points to the possibility they used objects for art. Again, if this is the case, it shows Neanderthals had symbolic abilities once thought to be uniquely human. In 2018 in Spain, more cave paintings of animals and geometric shapes were attributed to Neanderthals. This time they dated even earlier – to 64,000 years ago.

Cave paintings found in mainland Spain were created 20,000 years before modern humans arrived in Europe, possibly by Neanderthals some 65,000 years ago (Credit: Getty Images)

If they were capable of producing symbols like art and jewellery, it might not surprise you that recent studies indicate they also had sophisticated language abilities.

In one 2013 study looking at a bone known to be crucial for speech – the hyoid bone – a team found that the Neanderthal’s version worked just like ours.

If Neanderthals also had language then they were truly human, too – Stephen Wroe

The team, led by Stephen Wroe, from the University of New England, Armidale, NSW Australia, told me at the time that their computer model indicated Neanderthals could therefore speak just like us. At the time of his discovery, he said: "Many would argue that our capacity for speech and language is among the most fundamental of characteristics that makes us human. If Neanderthals also had language then they were truly human, too."

If they could speak, then they could efficiently transmit information to each other, such as how to make tools. They may even have taught us modern humans a thing or two.

Finlayson says the steep cliffs on Gibraltar have helped to preserve Neanderthal remains (Credit: Getty Images)

There is now evidence that suggests this is exactly what happened when Neanderthals and modern humans came into contact. A type of bone tool, discovered at a known Neanderthal site, later was also found where only modern humans lived.

The team, led by Marie Soressi of the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, analysed known Neanderthal sites from about 40-60,000 years ago. The tools they found were actually fragments of rib bones from deer and were most likely used to help make animal hide softer, possibly for clothes. "This type of bone tool is very common… in any sites used by modern humans after the demise of the Neanderthals," Soressi told me in an interview for BBC Earth.

This points to one thing, she says: the modern humans who had met Neanderthals copied their use of bone tools. "For me, it’s potentially the first evidence of something being transmitted from Neanderthals to modern humans.

When we lived closer to the equator, we didn’t have a need for warmer clothes. Neanderthals, on the other hand, had lived in the colder European climates for many years before modern humans arrived. Learning how Neanderthals dealt with the cold would have been of great benefit to us.

Many researchers, including Soressi, now argue that meeting other early humans may therefore have been crucial for us to become the successful species we are today.

Finlayson and colleagues at Gorham’s Cave – the last known place where Neanderthals lived? (Credit: BBC)

That Neanderthals used many different tools again reveals how similar they were to us. Like us, they were able to successfully adapt and exploit their environment.

"Neanderthals were much more evolved than what we used to think," Soressi says. "We are now at a turning point where we should consider that Neanderthals and contemporaneous modern humans were equal in many domains.”

This becomes even more apparent considering additional evidence that suggests they buried their dead, too – another important cultural ritual showing “complex symbolic behaviour”.

Last Neanderthals

But there were also clear differences between Neanderthals and modern humans. It is telling that we are here today and they are not. And as they reached the last few millennia of their existence, they were facing new challenges – ones they weren’t as well equipped to deal with as modern humans proved to be.

John Stewart of the UK’s Bournemouth University points to his work looking at the different hunting strategies of humans and Neanderthals. The latter, he says, did not exploit smaller game, such as rabbits, as much as modern humans did. Though there is some evidence from Gorham's cave that Neandertals hunted rabbits, Stewart says they hunted less of them than we did.

Their close-combat hunting tactics, which had served them well for larger game, may have made it much more difficult to catch enough rabbits to sustain them when other food was in short supply. "I think modern humans had more technologies to catch these fast-moving smaller prey items, like nets or traps. Certainly when times got tough modern humans always had more at their disposal," he says.

Climatic evidence shows that Neanderthals also were existing in an increasingly hostile environment. Extreme cold periods in other parts of Europe pushed them further south until they arrived in areas like Gibraltar.

"Every few thousand years in Europe and Asia, the climate was drastically changing from relatively warm to bitterly cold," says Chris Stringer, research leader in human origins at the Natural History Museum in London. "As this was happening over and over again, they were never able to build up their diversity."

A reconstruction of a Neanderthal burial at Chapelle-aux-Saints, France (Credit: Getty Images)

This means that by the time the last Neanderthals reached their final place on Earth they were very inbred – bad news for a population that was already dwindling.

At the same time, a 2019 finding also proposes that their fertility was declining, perhaps due to a lack of food, as infertility can be a result of decreasing body fat. The research paper, led by Anna Degioanni from the Aix-Marseille University in France, proposed that even “a slight change in the fertility rate of younger females could have had a dramatic impact on the growth rate of the Neanderthal [population] and thus on its long-term survival”.

For the last years, then, it was a numbers game. "The whole story of the extinction has to be looked at over a long period of time," says Clive Finlayson. Their population may have become so small that eventually they reached "a point of no return".

Unfortunately, this means that although the last Neanderthals were living in much the same way as their ancestors had done for many years before them, climatic changes meant that it was not enough to ensure their survival.

Large parts of the Neanderthal genome still lives on in modern humans (Credit: Alamy)

This in turn would have had a direct impact on their ability to innovate and spread culture. If life only becomes a battle for survival, other things like culture may fall by the wayside. In their last years on Earth, it would not have taken much competition from other humans, animals or disease to finish them off.

But while their species is said to be extinct, they are not entirely gone. Large parts of their genome still lives on in us today. The last Neanderthals may have died – but their stamp on humanity will be ensured for thousands of years to come.

--

Melissa Hogenboom is the editor of BBC Reel. She is @melissasuzanneh on Twitter.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.