How ‘Orwellian’ Became an All-Purpose Insult

Credit...Bettmann, via Getty Images

The New York Times

Jan. 13, 2021

After the events of last week, one has to wonder whether Josh Hawley — for all of his prep school polish and Ivy League degrees — was fully cognizant of what he was doing. The Republican Senator from Missouri apparently assumed he could have it all: Hitch his star to Donald Trump’s, attempt to overturn November’s presidential election, and prove his down-home bona fides by giving the mob that later invaded the Capitol a raised-fist salute — while also presenting himself as a Very Serious Thinker who had written a book about the wisdom of Teddy Roosevelt and was about to publish another titled “The Tyranny of Big Tech.” What he got instead was mostly revulsion from his congressional peers and a canceled book contract.

An irate and incredulous Hawley took to Twitter, calling the publisher’s actions “a direct assault on the First Amendment.” In peddling specious claims of voter fraud, he said he had merely been doing his duty, “leading a debate on the Senate floor on voter integrity.” He insisted that his publisher was taking its cues from “the Left” and trying to silence him: “This could not be more Orwellian.”

One might come up with things that are in fact “more Orwellian” — including the bland euphemism “voter integrity,” which typically serves the cause of disenfranchisement and not voting rights. (Just as one might question whether a single publisher scrapping a single book contract amounts to what George Orwell’s novel “1984” describes as “a boot stamping on a human face — forever.”) But Hawley was taking part in the long tradition of invoking Orwell’s name as a cudgel for settling scores and scoring points. The next day, after Twitter permanently suspended the president’s account, his son Donald Trump Jr. announced (on Twitter) that “free speech no longer exists in America” and “we are living in Orwell’s 1984.”

In the meantime, the novel “1984” — in which a totalitarian regime crushes dissent through violence and the perversion of language — shot to the top of Amazon’s best-seller list. Hawley may have bungled the rollout of his own book, but it looked like he helped buoy the sales of someone else’s.

It’s an irony that Orwell, ever alert to the stubborn discrepancy between reality and high-flown fantasies, might have appreciated. Or perhaps he would have despaired that his last novel, published in 1949, less than a year before he died, had been pressed into service as an impulse purchase (by anxious book buyers) and a weapon (by cynical politicians). Sales of “1984” are a barometer of national worry — they surged in 2013, after Edward Snowden revealed the vast scope of the surveillance state; and again in early 2017, after Kellyanne Conway, then serving as an aide to President Trump, defended demonstrable lies by calling them “alternative facts.” Even if Hawley’s critics have argued that his use of “Orwellian” is itself Orwellian, there’s a reason it’s become an all-purpose epithet, a go-to accusation. Americans in 2021 might not agree on much, but everyone can agree that the world depicted in “1984” is a dystopia — which is to say, it’s obviously and indisputably bad.

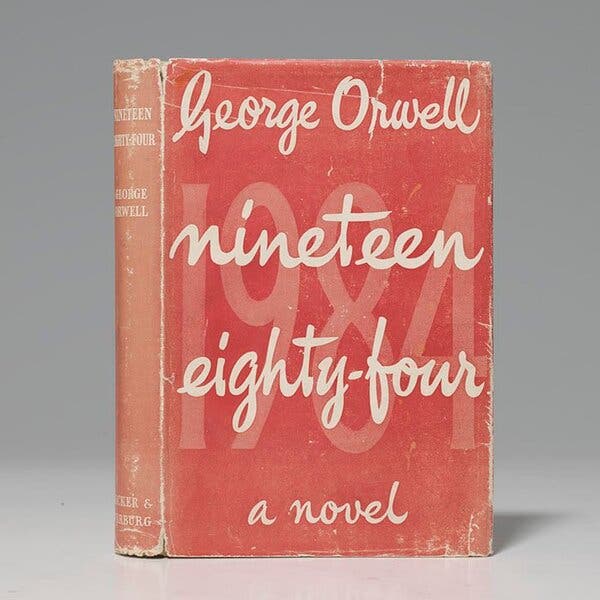

Image

Credit...Bauman Rare Books

Throughout his writing life, Orwell had been preoccupied with consensus reality — its necessity and vulnerability. In “Homage to Catalonia,” he chronicled his experience as a volunteer for anti-Franco forces during the Spanish Civil War, watching as the Republicans devoured their own. Once their shared understanding of the world began to break down, they started denouncing one another as liars and traitors to the cause. “In such circumstances there can be no argument,” Orwell wrote. “The necessary minimum of agreement cannot be reached.”

Orwell was an exceptionally prolific book reviewer and columnist, but it was his dystopian novels, “Animal Farm” and “1984,” that cemented his cultural legacy. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term “Orwellian” started as a literary critic’s playful shorthand, when the writer Mary McCarthy used it in a 1950 essay to describe a fashion magazine that had no “point of view beyond its proclamation of itself.” The word has since been used to describe such varied phenomena as the euphemistic jargon of the nuclear industry, the withdrawal of troops from Vietnam and a ’60s-era kitchen appliance that turned powdered mixes into coffee and soup.

You don’t need to have read “1984” to grasp why someone is calling something Orwellian, even if you disagree with the assessment. But someone who hasn’t read the book may be more susceptible to the manipulation of the term. Hawley, Trump Jr. and others on the right deploy the word to complain about “cancel culture,” but the novel itself isn’t so much a treatise on free speech absolutism as it is a warning about the degradation of language and the potency of lethal propaganda.

Still, even that is a flattened description of a novel that is more sophisticated than the leaden morality tale it’s often made out to be. In his illuminating book “The Ministry of Truth,” a biography of “1984” and its influence, Dorian Lynskey makes a persuasive case that the novel is structured in a way that heightens its ambiguity. Yes, the brute force of totalitarianism is an inextricable theme, but the novel’s narration — with its texts within texts — also enacts its own phantasmagoria, a world where both everything is true and nothing is true. Lynskey credits Orwell with anticipating what Hannah Arendt would describe in “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” published a year after Orwell died: “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

But the periodic invocations of “Orwellian” generally have less to do with the specifics of the text than with the writer’s noble sheen — Orwell as a stalwart man of the left who was never seduced by the extremes of either side. As Lynskey puts it, “To quote Orwell was to assume, deservingly or not, some of his moral prestige.” In 2002, Christopher Hitchens wrote a short book titled “Why Orwell Matters” that extolled Orwell’s independence of thought, implying that Hitchens himself was Orwell’s rightful heir. A year later, Hitchens was part of the chorus in favor of invading Iraq — a cause he would unwaveringly support until his death in 2011, even after the stated pretext for the war turned out to be a sham.

In “Politics and the English Language,” Orwell discussed the blight of “dying metaphors” — those well-worn phrases that allow us to mouth off without paying much heed. The examples he gave included “Achilles’ heel,” “swan song” and “hotbed.” Had he lived long enough, he may well have added “Orwellian” to the list.

'論評, 社說, 談論, 主張, 인터뷰' 카테고리의 다른 글

| What Will Trump’s Presidency Mean to History? (0) | 2021.01.18 |

|---|---|

| 세종이 조선 패망의 시발점? (0) | 2021.01.17 |

| “성공한 혁명, 곧 폭군 옷 입는다” (0) | 2021.01.11 |

| もし韓国でコロナに感染してしまったら…… (0) | 2021.01.04 |

| “내 젊은날 5·18 잃고 싶지 않아… ‘표현의 자유' 제약이 독재 첫걸음” (0) | 2021.01.04 |