Fall Preview

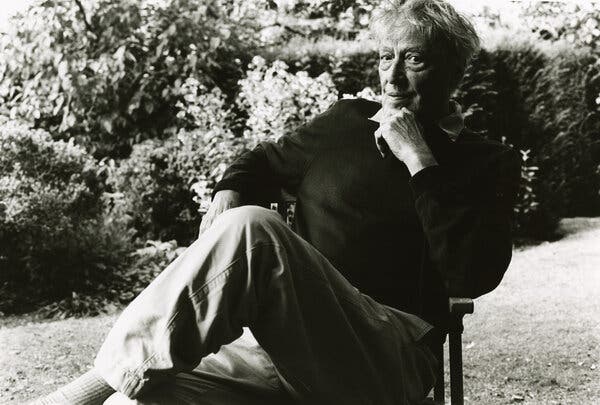

Tom Stoppard Finally Looks Into His Shadow

After years of living “as if without history,” the playwright belatedly reckons with his Jewish roots, and his guilt, in “Leopoldstadt,” his most autobiographical play.

By Maureen Dowd

The New Tork Times, Sept. 7, 2022

DORSET, England — Long before he became the august Sir Tom Stoppard, hailed by some as the greatest British playwright since Shakespeare, Stoppard was a teenage journalist in Bristol, making a few pounds a week covering lawn tennis, flower shows and traffic problems. He loved wearing a mackintosh and flashing his press pass, operating in the spirit of a British contemporary, Nicholas Tomalin, who wrote: “The only qualities essential for real success in journalism are ratlike cunning, a plausible manner, and a little literary ability.”

So Stoppard was ready to lend a hand when I arrived at his dreamy 1790s stone house called “The Rectory” (because it once was one) to talk about the Broadway debut of his heart-rending epic, “Leopoldstadt,” which begins previews Sept. 14 at the Longacre Theater and opens Oct. 2.

“I thought about you coming, and I thought I must try and help you be a success at this interviewing thing,” he said, in his seductively dry tone. “And I thought, oh, I’ll show her my cigarette box. That would definitely be worth a couple lines.”

He held up the elegant silver box, and as long as he was at it, took out a cigarette, the first of many he’d smoke over the next three hours. (He used to write by cigarette time, laying out a row of matches with his smokes and saying, “Tonight I shall write 12 matches.”)

“This says, ‘Christmas, 1967. Affectionately, David Merrick,’” Stoppard said. The big Broadway producer was “fearsome,” as Stoppard put it. He brought the young writer to New York that year with “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” the darkly funny worm’s eye view of “Hamlet” that transformed Stoppard’s life, imbuing him with an image as the Mick Jagger of theater, a dashing icon of ’60s Swinging London. As his friend and fellow playwright Simon Gray said, Stoppard was a magnetic figure blessed with so many enviable gifts — talent, riches, looks, luck — that it was futile to envy him.

When Stoppard landed in New York that year he was the toast of the town, as his biographer, Hermione Lee, writes in “Tom Stoppard: A Life.” Marlene Dietrich came to see his play; Walter Winchell drove him around to crime scenes in a car with a siren. New Yorkers began asking him whether he was Jewish. He would respond vaguely that there must be “some Jewish somewhere.” Borrowing an old Jonathan Miller line, he would say he was “Jew-ish.” He breezily called himself “a bounced Czech.”

Fifty-five years later, Stoppard is returning to New York with “Leopoldstadt,” a play inspired by his belated reckoning with his Jewish roots.

The man who writes so brilliantly about time travel was ready to time-travel with me. He settled back on the couch in his sitting room, wearing a green sweater and khakis, still lanky and still with a tousled — but more silvery — mane. At 85, he retains, as Daphne Merkin once wrote in The New York Times, a louche glamour, “like a lounge lizard who reads Flaubert.” The house Stoppard shares with his third wife, the charming Sabrina Guinness, is exactly what you would expect: elegant, erudite, fey and library-quiet. No tapping, since Sir Tom has no computer and is not on social media. He lets Guinness email for him, and he still writes with a Caran d’Ache fountain pen with a six-sided barrel.

There is a bookcase full of first editions of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, which gets raided by “American burglars,” as he calls his novel-purloining friends. In the hall hang framed letters Stoppard has collected, including one from A.E. Housman (the subject of his play “The Invention of Love”) to the Warden of The Fishmongers’ Company and another from Albert Einstein to the National Labor Committee for Palestine. The most cherished one, dated 1895 and composed on stationery from the Albemarle Hotel in Piccadilly, is a flinty put-down Stoppard bought at auction as soon as he had money: “Sir, I have read your letter, and I see that to the brazen everything is brass. Your obedient servant Oscar Wilde.”

The bathroom features another whimsical collection, which Stoppard ordered from autograph collectors and booksellers in the ’70s: small, framed, signed publicity stills of Mae West, Marlon Brando, Elvis, Brigitte Bardot and others. Pointing out Frank Sinatra, Stoppard said regretfully that the signature had faded from too much sunlight.

Once or twice, when Stoppard was working on the arts page of the Western Daily Press and had more than one story to write, he used a different byline on the second one, so as not to look “too provincial.” It was Tomáš Sträussler, his own name before his widowed mother remarried a British army major she had met in India named Kenneth Stoppard.

Tommy immigrated to England at 8, assuming an identity as British as white flannel cricket pants. It was a duality he did not dwell on for decades. Even when he was eventually prodded in his 50s into examining the identity of his Eastern European family and their fate in the Holocaust, it would take him six more years to write a magazine piece about it, and then two more decades for the play to gestate.

“I think he’d already faced it, but he hadn’t faced it all the way through his body to be sufficiently able to write it,” said Patrick Marber, the playwright (“Closer”) who directed “Leopoldstadt” as well as the successful revival of Stoppard’s “Travesties” a few years ago in London and on Broadway. “It’s looking at his Jewishness, but it’s Tom looking at death and his own mortality and everyone’s mortality as well.”

Stoppard’s early life was defined by a series of escapes, and those escapes led to elisions. He showed me a painting of a sepia photo of his mother, Marta, when she was young, giving a fetching smile, flashing her son’s brown eyes, wearing a coat with a fur collar. “When you look closely,” he said, “it was a cheap coat.”

She married Eugen Sträussler, a doctor working in Zlín in Moravia, Czechoslovakia, for a shoemaking company called Bata, which ran the town. In 1939, after Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia, the Sträusslers fled to Singapore, where Bata executives had arranged a new job for Eugen. Tomáš was 18 months old.

Singapore fell to the Japanese when Stoppard was 4. He and his older brother, Petr (later Peter), and Marta were put on a ship that she thought was headed for Australia but turned out to be steaming toward India. His father tried to follow them but never made it; Stoppard would later learn that his ship had been bombed and sunk. (He has nothing his father owned or touched.) With her future uncertain, Marta made her third and final escape to England by marrying Major Stoppard.

Tomas fell in love with all things English and followed his mother’s lead in not looking back. She played down her history and Jewishness, thinking she had delivered her boys to safe harbor.

The cascading escapes made Stoppard feel as though he had “this charmed life.”

“I was scooped up out of the world of the Nazis,” he said. “I was scooped up out of the way of the Japanese, when women and children were put on boats as we were being bombed. I was just put down in India where there was no war. The war ended, my mother married a British army officer and so instead of ending up back in Czechoslovakia in time for Communism — they took over in 1948 when I was 11 — here I was, turned into a privileged boarding-school boy. I was just going on, saying ‘Lucky me.’”

Eventually he was scooped up by the London theater world. But at some point, after some backlash, he turned the concept inside out. What about those who hadn’t been lucky?

“I remember very clearly saying to my mother, ‘Well, how Jewish were we?’ and she didn’t come clean at all,” Stoppard told me. “She said, ‘Well, in 1939, just to have a Jewish grandparent was dangerous.’ I just thought, ‘Oh, I see. OK.’

“My mother essentially drew a line and didn’t look back. My name was changed, I was British, and I really began to love England in every sense — the landscape, the literature. I don’t recall ever consciously resisting finding out about myself.

It’s worse than that. I wasn’t actually interested. I was never curious enough. I just looked in one direction: forward.”

He came to think of himself as “Anglo-Saxon,” he said: “Church of England is barely a religion if you don’t want it to be one. You go to church every Sunday with the rest of the school. I’m not sure when I first was inside a synagogue, but it was years and years and years later.”

As he wrote about his mother in a searing 1999 Talk Magazine article, “‘being Jewish’ didn’t figure in her life until it disrupted it, and then it set her on a course of displacement, chaos, bereavement and — finally — sanctuary in a foreign country, England, thankful at least that her boys were now safe. Hitler made her Jewish in 1939.”

Stoppard told me, “Obviously, I knew that there was a reason why we’d fled from the Nazis, but I didn’t quite join the dots. My mother was always terribly nervous about my Czech past catching up with me.”

As he ascended to be the new prince of London and New York theater with “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” his mother was fretting. “When I was about 30, people were writing about me being from Czechoslovakia, and so on,” he recalled. “It made her very uneasy, and she thought there was surely some way I could do these interviews without letting on that my name wasn’t really Stoppard, and that kind of thing.”

In 1993, a cousin, Sarka Gauglitz, who lived in Germany, got in touch. She came to the National Theater in London for lunch to talk to him and his mother about their Jewish family history.

“There was this weird scene where I said to Sarka, ‘How Jewish are we?’ and then she said, ‘What? You’re Jewish.’ I said, ‘Yes, yes.’ I was embarrassed. So I’m kind of going, ‘Yes, I know I’m Jewish, but how?’ So she then drew this family tree.”

She told him how his four grandparents had perished at the hands of the Nazis and how his mother’s three sisters had died in Auschwitz and another camp — a horrific litany that is echoed in “Leopoldstadt.”

“I was totally poleaxed,” he said. “I was in my 50s. I’d had this entire life. I couldn’t change it retroactively even in my mind. So it wasn’t like some kind of new start. I just carried on being the person I was.”

The next year, when he went to Prague for a PEN conference and to see his friend, President Václav Havel, he visited the synagogue where the names of his grandparents were inscribed as Holocaust victims.

When his mother died in 1996, his stepfather — who had not welcomed her Czech family in their home, and whom Stoppard and his brother had come to see as xenophobic and antisemitic — asked Tom to renounce his last name. Stoppard told me he was “shocked” by the request, which he ignored, chalking it up to his stepfather’s grief.

Stoppard was later moved by a novel called “Trieste” by the Croatian writer Daša Drndić. One of the characters rips into real-life people, including Stoppard and Madeleine Albright, saying they took too long to discover their family history, calling them “blind observers” who played it safe.

“Basically, she was saying, enough already with the charmed life, you had this family, which you seem to have forgotten,” Stoppard said. “And I thought that was completely legitimate and an intelligible thing to say. And I think it had a lot to do with choosing to write about it.”

Marber called the novel “an intense bee sting” for Stoppard, adding: “Tom is a ruthlessly truthful man in private.”

Stoppard wrote another play first, “The Hard Problem,” about human consciousness and the question of whether people can be genuinely good. The final spur for his most serious, personal play came, oddly enough, when he was joking around with his longtime producer Sonia Friedman several years ago.

He told Friedman he needed six impossible-to-get tickets for “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child,” which she produced, for his niece. “She said, ‘OK, if you write me a play,’ and I said, ‘OK.’” When he was forced to think about it, he realized that he had a play all along. He had to break the news to Friedman that they would need a company of about 40 actors.

“Of course, it’s autobiographical without really being an autobiographical piece,” he told me. “But elements of it are completely taken from life.”

He said he had “displaced” the enormity of learning about his family by reading a lot about Auschwitz, and other people’s stories. He wanted to set the story in Vienna, which he had visited in other plays.

“It was because I personally didn’t have the background I wanted to write about — bourgeois, cultured, the city of Klimt and Mahler and Freud,” Stoppard said. “Where better than Vienna? It’s got an incredibly rich society.”

Lee, his biographer, noted that Stoppard was particularly influenced while researching “Leopoldstadt” by Alexander Waugh’s book, “The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War,” about the wealthy, sophisticated Viennese family that produced the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and his brother Paul, who continued to be a concert pianist after losing an arm in World War I. The family had been Catholic for two generations, but when Hitler annexed Austria, they were stunned to learn they counted as Jews.

This is what happens in “Leopoldstadt” to the Merz family, a clan of businessmen, professors and musicians who become prosperous and bourgeois in Vienna, leaving behind the Jewish quarter, Leopoldstadt, and presiding in a large apartment on the desirable Ringstrasse. They intermarry and convert into an uneasy blend of Jewish, Protestant and Catholic, celebrating Christmas and gathering for a Seder. They argue about the merits of a Jewish homeland versus assimilation.

“So don’t fall for this Judenstaat idiocy,” one character declares. “Do you want to do mathematics in the desert or in the city where Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven overlapped, and Brahms used to come to our house? We’re Austrians. Viennese.”

When the dreadful knock on the door comes, they are stunned.

Stoppard does something unusual, ending his play with three characters who have barely appeared. In 1955, a young Englishman shows up named Leonard Chamberlain, who was born Leopold Rosenbaum. He immigrated to England at 8 (as Stoppard did), took his stepfather’s name (as Stoppard did), has grown up to be a witty British writer (as Stoppard did) and had “a charmed life” (as Stoppard did). It is an unflattering self-portrait. Leo, contentedly vague about his identity, must listen to the litany of Holocaust deaths recited to him by his cousin, just as Stoppard did with his cousin.

His cousin Nathan tries to get through to Leo, speaking what Stoppard says is the essential line in the play: “You live as if without history, as if you throw no shadow behind you.”

The Leo character, Stoppard told me, was “written out of a kind of guilt.”

Stoppard, who was raised knowing little about Judaism, turned to friends while writing the play, seeking advice for a scene involving a bris and discussing Seders with Fran Lebowitz. (“Only compared to Tom Stoppard am I a knowledgeable Jew,” she said.) When Stoppard threw in an “Oy, vey,” Marber cut it back to “Oy.”

“I think there’s a way of being consciously in denial, I guess, but also there’s a way of being unconsciously in denial,” Stoppard said. “You don’t know that you’re in denial, so you’re quite happy about being in denial. You think that’s your kind of resting place.”

He knows he can’t change things by agonizing, so he doesn’t.

“I don’t take things very hard,” he said. “Death, for example. People die, and I sidestep the moment in some way. Or if you just say something embarrassingly dumb to someone or you think you’re talking to one person but he’s actually somebody else. I’m vaguely aware that I have a capacity not to dwell on this. I can see that there’s another way to live where you’re lying awake about it. I just think, ‘Move on and to hell with it.’”

Critics have long debated whether Stoppard’s verbal acrobatics and cerebral obsessions have deflected emotion in many of his plays, but Lee thinks this is misleading, that sadness, mortality, melancholy, vulnerability, the sense of being an outsider thread through his work.

At first, Stoppard resisted the idea that his work should have a moral or political message — “the whiff of social application.” As the Malquist character in his novel, “Lord Malquist and Mr. Moon,” said, “Since we cannot hope for order, let us withdraw with style from the chaos.” Stoppard himself liked to say, in Wildean style, “I should have the courage of my lack of convictions.” But history drew the onetime “apostle of detachment,” as the drama critic Kenneth Tynan called him, into more intense commitments. In 2013, he shared the PEN Pinter Prize for his work opposing human rights abuses.

“Leopoldstadt,” Marber said, “is a really angry play. It’s a play about murder, a terrible, terrible state murder, and how did this crime happen?”

Stoppard told me that when he started his career, he did not want to appear in his work “in any guise.” He gradually grew less bottled up.

“Then, I think, with ‘The Real Thing,’ I didn’t care so much,” he said of his play about a dazzling playwright’s affair with an actress, a topic Stoppard would come to know something about, given his liaisons with Felicity Kendal and Sinéad Cusack. “Now, with the last few plays, I really want to encourage the play to be emotional. A woman reviewing ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’ wrote that she started crying when the love story got together at the end, just in time. I was aware that I was more pleased by that than any number of people telling me that I was too clever by half or intellectual.

“In fact, the reason I liked it so much was that I was two-thirds of the way through writing it before I began to understand that there was a love story in it. I’m very much in favor of love.”

We had moved to the big country kitchen to eat a lunch Guinness had prepared: niçoise salad, a platter of cheese, dry rosé, and a blackberry and apple tart. Sabrina beamed at her husband’s remark about love. Even though they have been married for eight years, and even though she was linked to celebrated men before Stoppard — including Prince Charles and Mick Jagger — she told me that she feels so lucky in this relationship, her first marriage, she has to keep pinching herself.

She confessed to Lee that she worried she was too “dim” for Tom, and I admitted I knew how she felt.

“I just wait for the day when you and others see through that,” Stoppard murmured.

I asked him how he liked Guinness calling him “drop dead gorgeous” in the biography.

“I never felt even remotely good-looking for my entire life,” he protested, always wary about being “over-esteemed.”

Friedman, his producer, said that, despite Marber’s description of Stoppard’s air of “kingly bonhomie,” the playwright is the most democratic person she knows. “Tom is as interested in the young child at the stage door who wants to ask how to become a writer,” she said, “as he is sitting next to a member of the royal family.”

He showed me some pince-nez reading glasses that Guinness has gotten for him, which make him look even more like an 18th-century European count. “I thought these were great,” he said, “because glasses sometimes interfere with my hearing aid.”

I talked with Stoppard — who wrote “The Coast of Utopia,” about Russian radicals in the 19th century, and “Every Good Boy Deserves Favor” about the psychiatric abuse of political dissidents in the Soviet Union — about the war in Ukraine.

“This wonderful nation of Russians, a superb, amazing country, has got into the hands of the wrong people, and I would love them to be defeated,” he said. He had worked for a year on a screenplay about Los Alamos, so he said the power of atom bombs was on his mind. “If I were prime minister or president and there was no nuclear weapon, I would’ve liked to have piled into Ukraine and made war. Because we are now all Neville Chamberlains — appeasement, appeasement.”

Is Stoppard surprised about the ascendancy of authoritarianism in Central and Eastern Europe?

“The very concept of an idealistic democracy is beginning to sound quaint,” he said. “Where is it now? It doesn’t feel like England, let alone Poland. The English are the most surveilled people anywhere.”

The man who once caused waves in the London theater community by praising Margaret Thatcher’s early tenure said he is “horrified” at the idea of former President Donald J. Trump coming back. “Whatever the shortcomings are of a liberal democracy, you have to live with the shortcomings and not use them as a reason to grab the steering wheel and just go somewhere else,” he said. “Because there is nowhere else which is as good. Nowhere else which is as humane.”

After “Leopoldstadt” opened in London, Stoppard said that he was deluged with messages. “It was just rather extraordinary how many people had families with similar stories,” he said.

His favorite anecdote: A bookseller he buys from in London told him about another customer, an Oxford academic in his 90s, who said he needed to change his shipping information because he now had a different name, a Jewish name.

“OK, fine,” the bookseller replied, “Do you mind me asking why you’ve changed your name?”

The academic replied, “Because I went to see ‘Leopoldstadt’ and decided to go back to my real name.”

I said that the Oscar-winning “Shakespeare in Love,” which he co-wrote, was one of my favorite movies and he thanked me and said it was a great experience. But he added that he did not want to work on any more movies “because I’m a playwright, and if I have a play to write, that’s all I want to do.”

He said he had often done script doctoring when actors, sometimes friends, requested that Stoppardian polish, like Glenn Close in “102 Dalmatians” (“You’ve won the battle, but I’m about to win the wardrobe”) and Sean Connery in “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.” (A hilarious section in Lee’s biography describes Stoppard’s notes on scripts for producers, which are surely like no other notes Hollywood has ever seen: he called one line “otiose and hi-faluting,” another “fudgy,” and christened one cut to a script “the Portia Note” because it was like saying “Let’s lose this pound of flesh.”)

I wondered what the couple do for fun, way out here in Arden, besides looking after Guinness’s garden of geraniums and daisies? Given that Stoppard told me he “adores” the Queen and living in a constitutional monarchy, and given Guinness’s friendship with Prince Charles, I wondered if they watched “The Crown”?

“I watched the first series of ‘The Crown,’ which I thought was pretty good, but in the end, I began to see that there was what you might call dramatic license,” Stoppard said. He thought it was “incredible arrogance and bad manners to dramatize people who are still around.” Guinness, protective of Charles, agreed, saying, “I think it’s so appalling.”

There was a stir — and a shudder — when Stoppard told the BBC, before “Leopoldstadt” opened in London’s West End in 2020, that he was slowing down and this might be his last play. But the world-class workaholic has, of course, taken it back.

Now Stoppard is mulling a play on moral realism, whether good and bad are objective truths, rather than subjective attitudes. Talking point: Is God a verb?

“I did think I could stop after ‘Leopoldstadt,’” he said wryly. “That feeling didn’t last long at all.”

'人物' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Blue-eyed Buddhist (0) | 2022.10.05 |

|---|---|

| 이스라엘의 國父, 초대 대통령 바이츠만 (0) | 2022.10.04 |

| 강성갑 목사 (0) | 2022.08.28 |

| 상해임정의 임시헌장을 기초한 소앙(蘇卬) 조용은 (0) | 2022.08.19 |

| Obituary: Olivia Newton-John (0) | 2022.08.09 |