The frenemies are at it again.

Despite all their longstanding shared interests, Japan and South Korea just

can’t find a way past their long and bitter history. At present they’re focusing

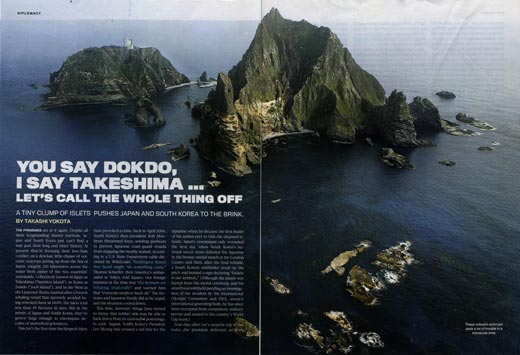

their love-hate conflict on a desolate little cluster of volcanic outcrops

jutting up from the Sea of Japan, roughly 210 kilometers across the water from

either of the two countries’ mainlands. Collectively known in Japan as Takeshima

(“bamboo island”), in Korea as Dokdo (“rock island”), and in the West as the

Liancourt Rocks (named after a French whaling vessel that narrowly avoided being

wrecked there in 1849), the islets total less than 19 hectares in area. But in

the minds of Japan and South Korea, they’ve grown large enough to encompass

decades of unresolved grievances.

This isn’t the first time the

flyspeck islets have provoked a crisis. Back in April 2006, South Korea’s

then-president Roh Moo-hyun threatened force, sending gunboats to prevent

Japanese coast-guard vessels from mapping the nearby seabed. According to a U.S.

State Department cable disclosed by WikiLeaks, Washington feared that Seoul

might “do something crazy.” Thomas Schieffer, then America’s ambassador to

Tokyo, told Japan’s vice foreign minister at the time that “the Koreans are

behaving irrationally” and warned him that “everyone needs to back off.” The

Koreans and Japanese finally did as he urged, and the situation cooled

down.

This time, however, things have

turned so messy that neither side may be able to back down from its nationalist

posturings. In early August, South Korea’s President Lee Myung-bak crossed a red

line for the Japanese when he became the first leader of his nation ever to

visit the disputed islands. Japan’s resentment only worsened the next day, when

South Korea’s national soccer team defeated the Japanese in the bronze-medal

match at the London Games—and then, after the final whistle, a South Korean

midfielder stood on the pitch and hoisted a sign declaring “Dokdo is our

territory.” (Although the player was barred from the medal ceremony and his

award was withheld pending an investigation of the incident by the International

Olympic Committee and FIFA, soccer’s international governing body, he has since

been exempted from compulsory military service and named to his country’s World

Cup team.)

Four days after Lee’s surprise trip

to the rocks, the president delivered an even more stinging slap to Japan. Out

of the blue, he announced that if Emperor Akihito ever expects to visit South

Korea, he should first apologize for Japan’s colonial rule of the peninsula

before and during World War II. Many Japanese regarded Lee’s words as an insult

to the emperor, and Japan’s legislators once again asserted their country’s

claim to the islets. Last week Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda infuriated the

South Koreans on another sore topic, saying there’s no evidence that proves

Japan’s imperial army forced Korean women to work as sex slaves. This week South

Korea intends to hold military exercises on the disputed islets, and Japan is

pondering whether to scrap a currency-swap deal with Seoul.

The falling-out is cause for

concern not only in Seoul and Tokyo but in Washington as well. Both are vital

U.S. trading partners and America’s most important allies in Asia, but more than

that: cooperation between them is essential in keeping North Korea in check. And

yet their quarrel has grown downright juvenile. When Noda sent Lee a letter of

complaint, the South Korean president declined to accept it, instead returning

it via a Korean diplomat stationed in Tokyo. The Koreans later mailed Noda’s

letter to the Japanese Foreign Ministry. “I’m sorry, but they’re behaving like

kids in a scuffle,” said a disgusted Tsuyoshi Yamaguchi, Japan’s senior vice

foreign minister. In the end, Tokyo accepted the letter’s return, rather than

“tarnish the dignity of Japanese diplomacy,” as Noda put it—advising South

Korean officials at the same time to cool their jets.

Japanese officials struggled to

make sense of Lee’s actions. The Korean president had always been viewed as a

pragmatist, more interested in building a “future-minded relationship” with

South Korea’s third-largest trading partner than in dwelling on past misdeeds.

“What happened to the guy?” Noda blurted out during a parliamentary session. The

most popular explanation points to Lee’s approval ratings, which had sunk to a

pitiful 17 percent. There’s a vicious cycle that has prevailed ever since the

advent of democratic rule in the late 1980s. Every five years, a new president

sweeps into office, pledging better relations with Japan. But by his third or

fourth year in office, the administration gets ensnared in a corruption scandal,

and the president becomes a lame duck. (In July, Lee found it necessary to

apologize publicly for a scandal involving his brother.) To rescue what’s left

of his presidency, he resorts to anti-Japan rhetoric, and relations with Tokyo

deteriorate—a trend that has grown stronger, especially in the past

decade.

Lee, who happens to have been born in Osaka, may

have felt a particular need to prove he’s not “pro-Japanese”—one of the most

poisonous accusations in South Korea’s political vocabulary. As a measure of how

deep that distrust runs, Lee’s national loyalties recently came into question

because he seemed ready to sign off on a deal to help the two countries share

military intelligence about their common enemy, North Korea. And in fact his

standing in the opinion polls rose by roughly 10 points after his visit to the

rocks. At the same time, however, Lee’s trip raises questions about his

integrity as a statesman. With only six months remaining in his term, why would

he jeopardize one of his country’s most important bilateral relationships in

exchange for a mere blip in his approval ratings? Even members of his

conservative Saenuri Party openly questioned whether his tactics were in South

Korea’s national interest. “The president’s office is resorting to populism,”

said lawmaker Choi Kyung-hwan, chief of staff to presidential candidate Park

Geun-hye. “And the next president is going to have to pay the

price.”

If the current feud is messy, the

history of the islets is even messier. Although both sides claim to have

documents dating back centuries proving that the rocks belong to them, they

insist that the other side’s documents actually describe some other islands in

the Sea of Japan. And the recent record is no less murky. In its 1951 peace

treaty with the Allied Forces, Japan relinquished much of the Korean territory

it had occupied during the war. But Tokyo argues that the islets were exempt

from the deal: the Japanese declared them part of Shimane Prefecture in

1905—five years before they annexed the Korean Peninsula. The Koreans see it

differently. In 1952, then-President Syngman Rhee unilaterally took control of

the islets by declaring a maritime demarcation line, and two years later, Seoul

sent troops to occupy the Liancourt Rocks. Tokyo calls that an “illegal

occupation.”

Tokyo has proposed for decades that

the two countries file the case for arbitration by the International Court of

Justice in The Hague. Last week Seoul once again refused. The Koreans say there

is no territorial dispute because the islets are theirs, and agreeing to a legal

arbitration would only contradict this logic. But according to the Japanese,

this only shows that deep down, Seoul suspects it might lose. “The Koreans are

insecure about their claims under international law,” contends Hideshi Takesada,

a Japanese professor of Asian studies at Yonsei University in Seoul. “That’s why

they feel the need to take measures to strengthen their control of the

island.”

In politically apathetic Japan,

Takeshima is usually a low-profile issue, not a cause for flag-burnings or

boycotts. For the Koreans, on the other hand, Dokdo is a sacred place that must

be protected at all costs, a proud emblem of their independence from Japan’s

colonial rule. “Besides being a territorial issue, Dokdo is about history,” says

former foreign minister Song Min-soon. “To the Korean people, Dokdo bears a

special, symbolic meaning—it symbolizes the 36-year occupation by the Japanese.

Whenever Koreans hear of the Japanese government’s claim [over Dokdo], they see

it as [proof of] Japan’s unapologetic attitude.”

That’s one more reason behind Lee’s

trip: he’s said it was meant to teach Tokyo a lesson. As South Koreans see the

situation, Japan hasn’t adequately atoned for the acts it committed in the first

half of the 20th century—including, according to Seoul, the forcible employment

of Korean women in military brothels. Lee was under pressure from the

Constitutional Court of Korea, which found last year that the government isn’t

doing enough to make Tokyo compensate the comfort women.

The South Koreans say the Japanese

just don’t get it. The Japanese respond that the Koreans are unreasonably

linking two entirely separate issues: rightful ownership of the Liancourt Rocks

and justice for the comfort women. As Noda recently expressed it, speaking to

the press corps in Tokyo, “The Takeshima problem is not an issue that should be

discussed in the context of historical interpretation.”

It’s not that Japan is oblivious to

its dark past, or unrepentant. Although the country’s right-wing politicians may

dispute the details of its imperial past, most Japanese recognize that many

terrible acts were committed in their country’s name. Nevertheless, even those

ordinary people are running out of patience with Seoul’s demands for apologies.

As they see it, Japanese prime ministers have apologized over and over. The

Japanese government actually set up a special fund back in 1995 to compensate

the comfort women. It ended in failure after right-wing activists in South Korea

persuaded several former comfort women not to accept the money, claiming that it

wasn’t an “official” compensation or apology from Japan.

Ordinary Japanese are baffled by the Koreans’

attachment to the islets. Since 2005, when Seoul began allowing tourists onto

the islets, visits—pilgrimages, some say—have become hugely popular. Last year

alone, some 180,000 people made the arduous trip. In 2010, civic groups,

together with the Korean Federation of Teachers’ Associations, declared Oct. 25

to be Dokdo Day, an annual occasion for teaching the nation’s schoolchildren to

love the remote island outpost. (Japan’s Shimane Prefecture celebrates a

Takeshima Day). Broadcasters go so far as reporting on the weather there, and

some television stations end their daily broadcasts with a video clip of Dokdo

as the national anthem plays.

Activists and political organizers

have been holding “Dokdo awareness” events around South Korea. At a July

gathering in Seoul promoting corporate social responsibility, small children

were encouraged to write “I love Dokdo” on cookies. And after Lee’s August

visit, a group of singers, actors, and college students braved the strong

currents and made a 220-kilometer relay swim to the rocks. So far the

demonstrations haven’t matched the extremes seen in March 2005, when a pair of

protesters each chopped off one of their fingers outside the Japanese Embassy in

Seoul, and another Korean set himself on fire. But the sense of outrage has not

gone away. Last week a protester in Seoul was arrested for throwing two plastic

bottles filled with feces at the embassy. (He reportedly turned out to be a man

who had previously severed one of his fingers and mailed it to the

embassy.)

In the face of such nationalistic

fervor, the South Korean government can scarcely back down. In fact, Lee’s visit

to the rocks has raised the ante for any future South Korean presidents who may

seek to prove their conservative credentials. Conservative presidential

candidate Park, the daughter of assassinated dictator Park Chung-hee, has

already said she will consider visiting the islets if she’s elected in December.

In the context of South Korean politics, her family background is a powerful

incentive to prove herself 100 percent Korean, untainted by “pro-Japanese”

attitudes: her father was a cadet at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy during

the war, and two decades later, as South Korea’s president, he’s the one who

normalized relations with Japan. His daughter can scarcely afford to give ground

on the islets, even if she thinks it’s the sensible thing to

do.

There seems to be no way out, at

least for the foreseeable future. Tokyo and Seoul could conceivably decide to

shelve the issue and muddle through, as they did after they normalized relations

some 50 years ago. It wouldn’t really solve the problem, but at least it seems

doable. Alternatively, an exasperated Park Chung-hee is said to have suggested a

more drastic approach at the time of the normalization talks: just blast the

islets into oblivion. Neither government is likely to buy that idea. But if

those rocks are going to keep causing so much trouble between the two Asian

frenemies, it might be the only real solution.

With Toshiyuki Chiku in Tokyo and

Jinna Park in Seoul